Posts Tagged "greenhouse gas emissions"

Green Light for Climate Action: Unveiling the impact of the GHG Emissions Measure rule

By mandating emissions tracking and target setting, the GHG Emissions Measure addresses an urgent need for climate action. And while this popular rule is an important first step, its success hinges on immediate and effective action at the state and local levels, which would signify a shift towards a cleaner, and greener, transportation landscape. On […]

Advocates call for White House council to track and reduce emissions

While NEPA exists to protect the environment and communities, it has long fallen short of addressing climate emissions and protecting disadvantaged communities. In response to a call for comments about new guidance on climate change and greenhouse gas emissions, Transportation for America joined a nine-member working group to urge the White House to address transportation’s role in climate emissions and historic injustices.

No time to lose: Federal rule ready to boost awareness of transportation emissions

Comments close tomorrow 10/13 on a greenhouse gas emissions rule that could reestablish sunlight and accountability for transportation’s impact on climate change. Here’s what’s next for the proposed measure.

Four ways states and the Biden administration can curb transportation pollution

Last month, the US Department of Transportation (USDOT) proposed a new rule that will require states to measure and set goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions associated with highways. Here are four ways the administration and the states can lead the way in realizing its full potential.

Transportation for America applauds new emissions rule, “a vital first step”

In response to the USDOT’s newly proposed rule for states and municipalities to track and reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, Transportation for America Director Beth Osborne offered this statement.

A way to improve the infrastructure deal

We strongly urge you to support the transportation programs proposed for the budget reconciliation package, which will help fill the gaps left by the bipartisan infrastructure deal.

Three ways reconciliation can restore funds taken from transit and equity

With the bipartisan infrastructure deal approved by the Senate, opportunities to shift long-term transportation policy will shift to the House and to program implementation. The opportunity in the House is through targeted investments via the budget reconciliation bill that will accompany the House infrastructure bill vote.

The Generating Resilient, Environmentally Exceptional National (GREEN) Streets Act re-introduced in the Senate today

Today, Senators Ed Markey (D-MA) and Tom Carper (D-DE), and Representative Jared Huffman (CA-02) re-introduced a bill that would measure and reduce greenhouse gas emissions and vehicle miles traveled. This would be transformative. We originally wrote this blog when the bill was first introduced in July 2019—we hope that 2021 is the year it becomes law.

Over 75 organizations and elected officials want the greenhouse gas performance measure reinstated

Reducing transportation emissions is necessary to slow down climate change. Which is why in less than a week, over 75 organizations and elected officials signed a letter by Transportation for America urging the Biden administration to reinstate the greenhouse gas (GHG) performance measure for transportation. This letter supported a similar effort in Congress led by Senator Cardin and Rep. Blumenauer.

House’s new climate action plan takes a page from T4America’s playbook

Last week, the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis released a new legislative blueprint for tackling climate change that incorporates a number of T4America’s recommendations. The blueprint goes beyond merely electrifying vehicles to take a much wider view—prioritizing repair, safety, and access, and promoting transit, biking, and walking.

House transportation bill goes big on climate

House transportation leaders introduced legislation to update our national transportation program to address climate, equity, safety and public health. Climate advocates and climate leaders on the Hill should recognize the strides taken with this proposal from Congress and fight to protect those changes in the bill.

House bill sets new standard for GREEN Streets

Last week, Rep. Jared Huffman (CA-02) introduced a bill that would measure and reduce greenhouse gas emissions and vehicle miles traveled on our roadways. This would be transformative.

The Generating Resilient, Environmentally Exceptional National (GREEN) Streets Act introduced in the Senate today

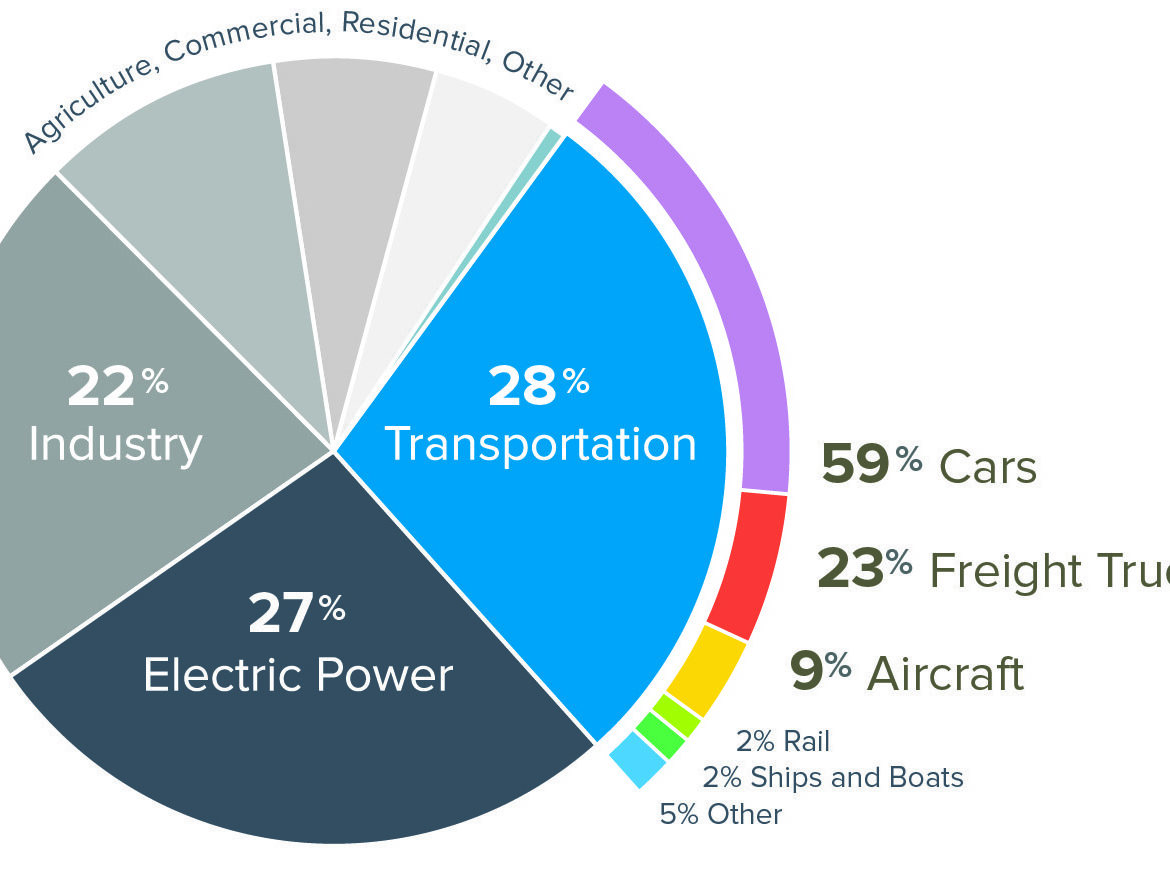

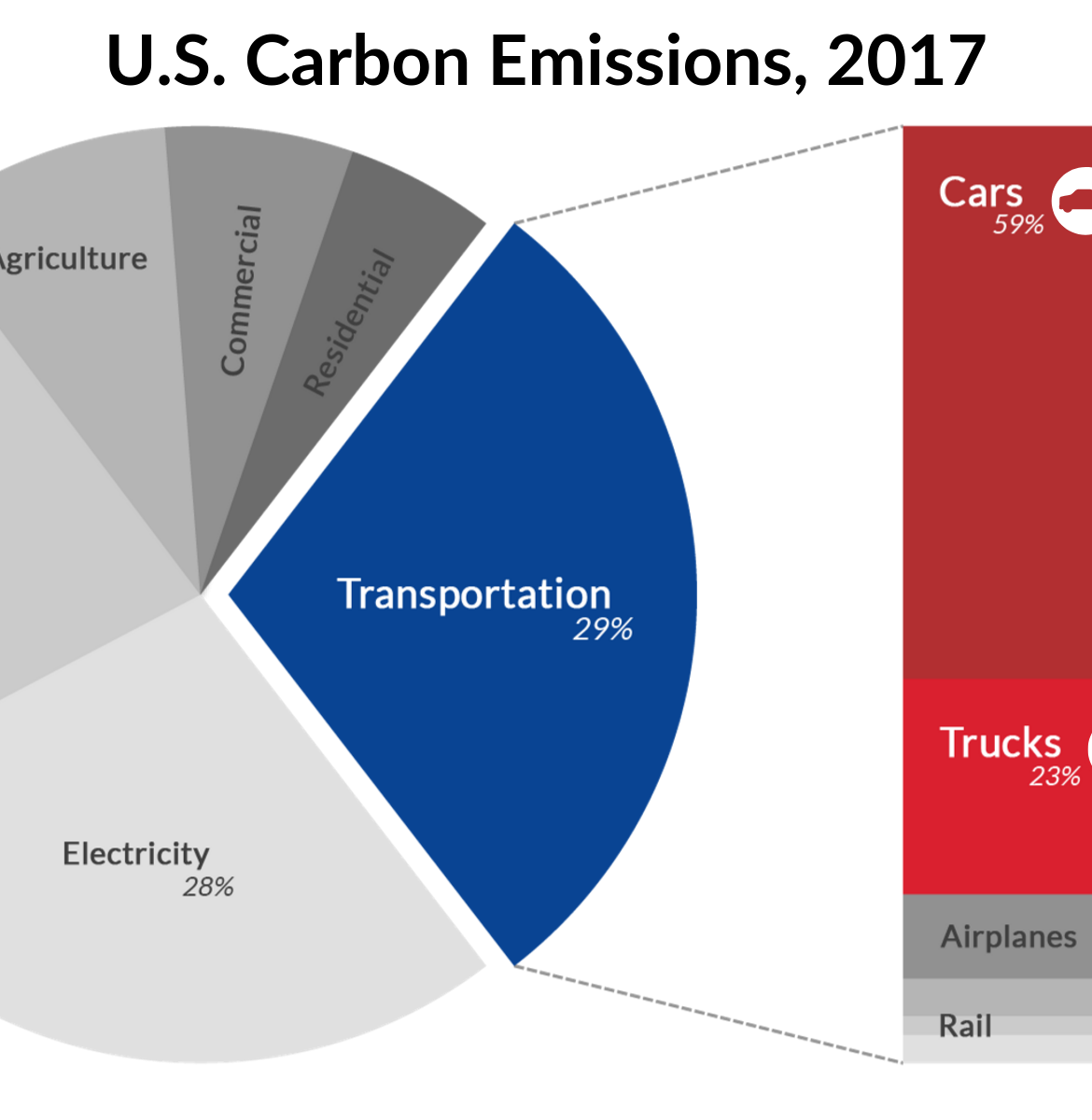

Today Senators Ed Markey (D-MA) and Tom Carper (D-DE) introduced a bill that would measure and reduce greenhouse gas emissions and vehicle miles traveled. This would be transformative. Transportation is the single largest source of greenhouse gases (GHG), contributing 28 percent of the United States’ total GHG emissions. While many other sectors have improved, transportation […]

What to watch for in Tuesday’s transportation and climate change hearing

The intersection between climate change and transportation will be on full display during a committee hearing in the U.S. House of Representatives. But will members of Congress take the opportunity to examine the critical role that federal transportation policy has played in creating the climate crisis? Here are six things we’ll be looking for during the hearing.