The opening of LAX/Metro Transit Center Station on the Los Angeles Metro is a major milestone in the city’s history and is vital for the 2028 Summer Olympics, but there are far more reasons to invest in alternative transportation options beyond major sporting events.

A Los Angeles Metro Rail C Line Train at LAX/Metro Transit Center during the testing phase (Source: LACMTA)

The grand opening of a long awaited station

This year, the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (LACMTA) plans to open the LAX/Metro Transit Center Station on the Los Angeles Metro Rail C and K Lines to serve Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). Despite having the second highest population of any city in the United States behind New York, Los Angeles did not provide rail transit service to LAX (the 8th busiest airport in the world) until 2025. While there is still work to be done on the LAX Automated People Mover (expected to open in 2026) to connect the transit center to the terminals at LAX without the need for a shuttle bus, the opening of LAX/Metro Transit Center is still a major milestone. LA has proven that it is committed to investing in the rest of its transportation system by heavily expanding the LA Metro Rail system and improving frequency and reliability on the LA Metro Bus network.

The LAX/Metro Transit Center Station is part of a larger set of projects known as the Twenty Eight by ‘28 plan in order to ensure Los Angeles and its transportation network are ready for the upcoming Olympic Games in the summer of 2028. Other upcoming notable projects part of the plan include the three phases of the D Line Extension along Wilshire Boulevard to the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), an extension of the A Line to Pomona, bike lane and pedestrian path improvements along the Los Angeles River, and more. Many of these projects are important initiatives to incentivize other methods of transportation beyond driving and will greatly benefit the local residents beyond the Olympics and the influx of people it will bring.

Competing Priorities for “Car-Free Games”

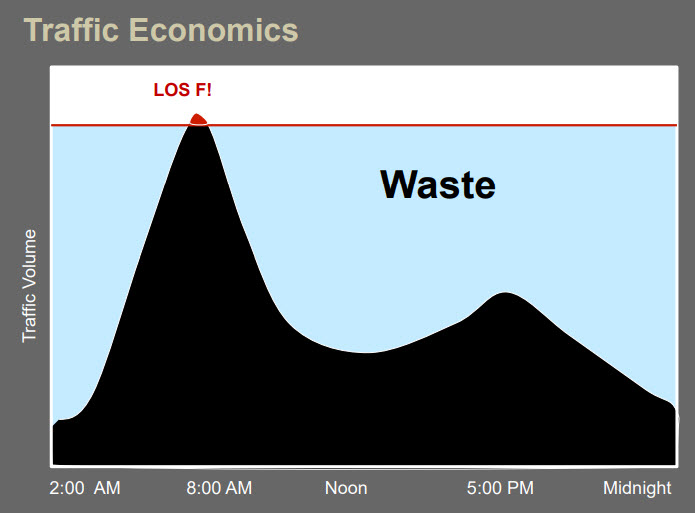

Los Angeles is a city well known for its car culture and particularly for its traffic. However, Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass has stated that the 2028 Olympics will be a “no-car games. This is a tall order for LA, and such an investment will require cooperation from the federal, state, and local levels. However, this mission statement by Mayor Bass aims to avoid congestion by making transit and active transportation the primary focus of the city for the Olympics.

These Olympic Games are a prime time to build transit better in LA, and show the world that a car-free Olympics is possible, even in a city famous for its traffic. In addition, these policy decisions to prioritize alternative transportation for the Olympics will have broad implications beyond the games themselves, as the transit improvements such as the A and D Line Extensions will permeate far beyond the Olympics in 2028, and greatly enhance how Angelenos move throughout the region.

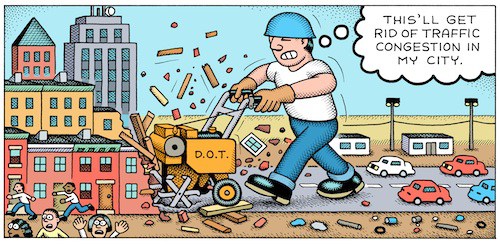

However, it is important that Mayor Bass and the LA Metro follow through with their vision for a car-free games. The need to focus on traffic alleviation and unsafe freeway interchange has prompted LA Metro to shift their focus to freeway expansions, including Express Lanes in I-105, increasing capacity at the interchange of State Routes 57 and 60, and expanding capacity for I-5. These projects run counter to the notion of a car-free games and should be re-examined in favor of other, smaller multimodal improvements which emit less carbon and cause less congestion.

Beyond the Olympics

By focusing on other methods of transportation such as cycling, walking, and many modes of public transit from buses to light rail and heavy rail, LA is creating options for moving around the city beyond driving that will last far beyond the 2028 Olympics. Oftentimes, after the Olympics, many of the facilities built and used for the events end up being underutilized and expensive to maintain (also known as a white elephant facility). By primarily investing in mobility options and reusing existing facilities, LA is creating a lasting mobility legacy beyond the Olympic Games.

A local coalition started by Move LA (the only countywide organization dedicated to public transportation funding that passed transformative initiatives like Measures R and M), FASTLinkDTLA, Agency Artifact, LA Commons, LA Neighborhood Initiative, and the California Community Foundation have come together to create the “Festival Trail” as a legacy project. This 28-mile-long zero-emissions, non-vehicular corridor connects the major venues currently proposed for the 2028 Games in the greater LA region. The Festival Trail is a linkage to current and planned Caltrans, LA Metro, and LA city projects with new public spaces celebrating each community and unlocking up to 20,000 units of new affordable housing in the most under-resourced communities of south LA and downtown.

Ideally, it should not take a major sporting event such as the Olympics to see the benefits of public transit, cycling, and other alternative transportation improvements. Building more public transit, both bus and rail, and investing in cycling and pedestrian pathways should be principles that cities across the United States implement regardless. But these mega-events do provide a deadline to move these projects along at a much faster pace. If a city so famous for its car culture such as Los Angeles can understand the value of alternative transportation, any city can.

Even in the San Francisco Bay Area, a renowned transit hub with higher than average rates of walking, biking and transit ridership, more than 280,000 vehicles cross the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge every day. It’s a critical artery connecting downtown San Francisco with the thousands of residents who live in Oakland and the surrounding suburbs.

Even in the San Francisco Bay Area, a renowned transit hub with higher than average rates of walking, biking and transit ridership, more than 280,000 vehicles cross the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge every day. It’s a critical artery connecting downtown San Francisco with the thousands of residents who live in Oakland and the surrounding suburbs.

A recent California Supreme Court decision could restore billions in funding for public transportation in the nation’s most populous state.

A recent California Supreme Court decision could restore billions in funding for public transportation in the nation’s most populous state.