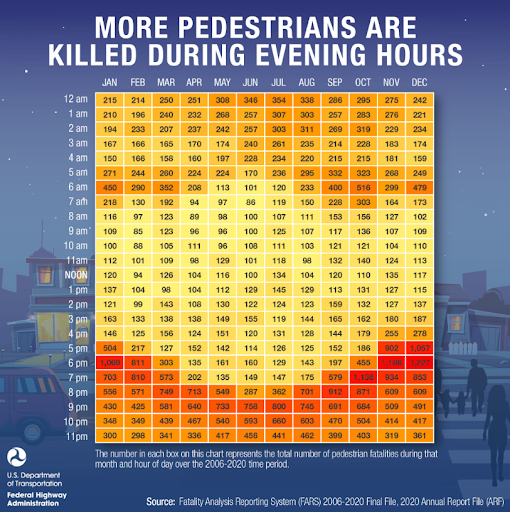

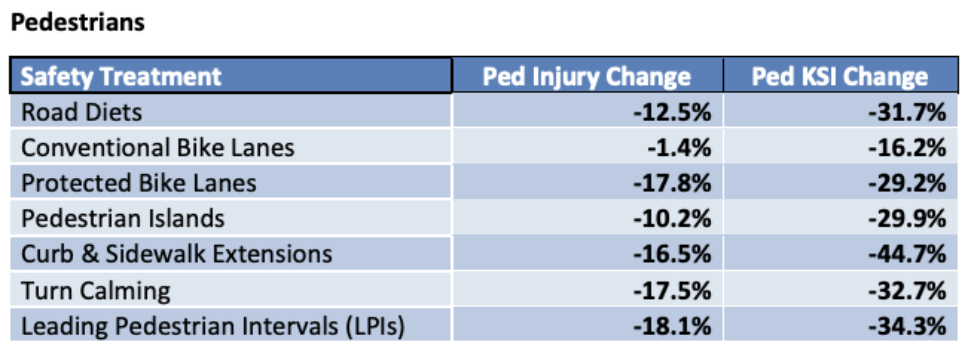

It will take years to unwind decades of dangerous street designs that have helped contribute to a 40-year high in pedestrian deaths, but quick-build demonstration projects can make a concrete difference overnight. Every state, county, and city that wants to prioritize safety first should be deploying them.

Quick-build demonstration projects are temporary installations to test new street design improvements that improve safety and accessibility. Here are three reasons why you, your elected leaders, and your transportation agency should have them as a tool in your arsenal:

1. Improve safety quickly in the most dangerous places

If elected leaders or transportation agencies are truly committed to safety, they must consider ways to improve immediately.

Transportation in this country often moves at a snail’s pace. Between planning, community engagement, and construction, adding safe infrastructure can take years. But that can leave dangerous conditions unchanged for far too long. If the number one goal is safety, and we know where the most dangerous places are, then we should be doing everything possible to fix them as quickly as possible.

As opposed to the years required for many capital projects, quick builds can go up in a matter of a week, addressing pressing issues immediately. While we should plan long-term safety projects, making safety the number one priority means doing everything we can to implement change in the meantime.

2. Cheaply test specific designs, interventions, and materials

Transportation departments are rightfully worried about building things that will be in place for the next 30 years. It’s hard to move concrete once it’s poured. That is precisely why quick builds need to be used more.

While permanent changes to infrastructure may need years to plan, temporary measures that use paint and plastic don’t require the same level of deliberation. A quick build can test out possible designs using building materials that transportation departments already have on hand. The beauty of this is that it allows you to test a concept in real life (at very low cost), get feedback, and make it better. Quick builds can be iterated upon and provide data inputs for future, permanent projects.

Quick builds can also help foster vital partnerships between local transportation departments and state DOTs. The deadliest roads are owned by the states, with 54 percent of pedestrian deaths taking place on these roads. If localities want to design roads for safety and economic activity while a state DOT wants to move cars as quickly as possible, this can lead to friction. Quick builds allow these stakeholders to learn how to work with each other. Smart Growth America’s Complete Streets Leadership Academies put this idea into action in multiple states.

3. Build needed trust for stronger permanent projects

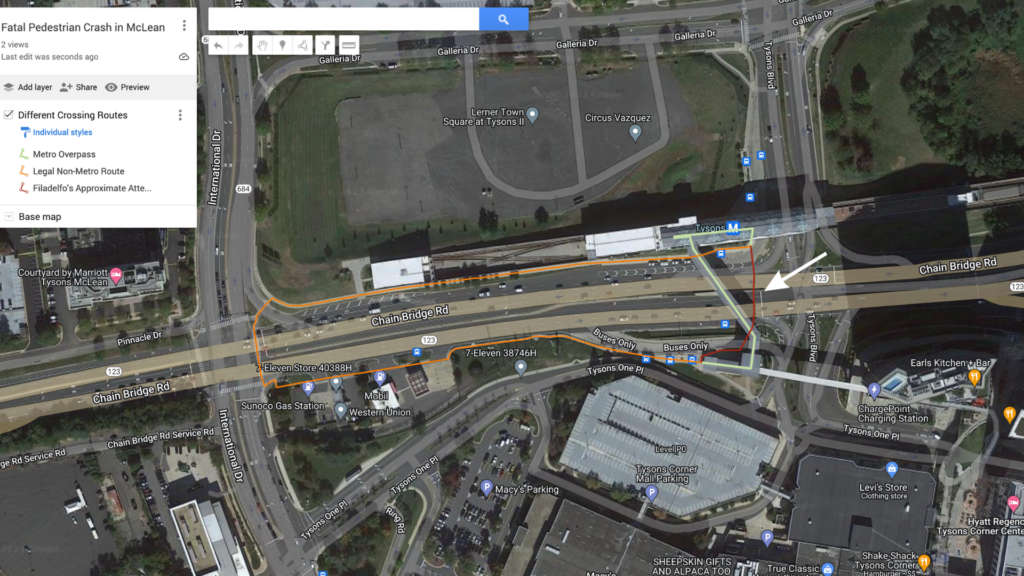

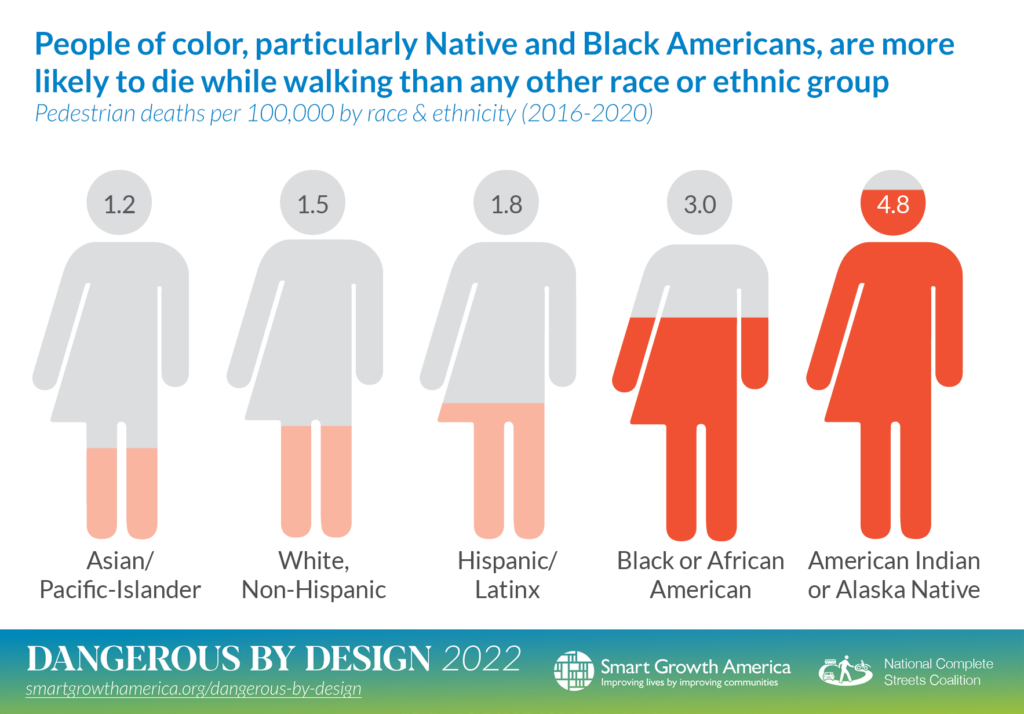

Building highways through neighborhoods and continually ignoring communities has led to a situation in which low-income and minority groups are disproportionately harmed by traffic violence. It takes years to build up trust in places that have been disregarded. Quick builds can help the process of restoring relationships by demonstrating the responsiveness of local agencies, showing that change is possible. If someone is killed in an intersection, swiftly changing the intersection means much more in comparison to filing a potential improvement away in a list of projects years from implementation.

How federal leaders can help

State DOTs look to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) for guidance. FHWA has communicated that quick builds are allowed on state-owned roads, but that’s about as far as it goes—leaving state DOTs to do the heavy lifting on figuring out how to implement one in their state. This piecemeal approach means progress can be slow as each state works alone to discover best practices. To help make more quick builds a reality, the FHWA can provide a proactive guide to quick builds on state-owned roads and run training sessions for state DOT employees and FHWA regional offices.

So much of our transportation policy is based on a reactive response to issues. We wait for someone to get killed on a road, the community speaks out, and then the department of transportation (sometimes) acts. Quick-build demonstration projects are excellent ways to change road design today and are an important tool to finally prioritize speed over safety, but the work can’t end there. Quick builds are just the first step in building a safe transportation system. They are templates for a permanent, future change where safety is prioritized over speed.

It’s Safety Over Speed Week

Click below to access more content related to our first principle for infrastructure investment, Design for safety over speed. Find all three of our principles here.

-

Three ways quick builds can speed up safety

It will take years to unwind decades of dangerous street designs that have helped contribute to a 40-year high in pedestrian deaths, but quick-build demonstration projects can make a concrete difference overnight. Every state, county, and city that wants to prioritize safety first should be deploying them.

-

Why do most pedestrian deaths happen on state-owned roads?

Ask anyone at a state DOT, and they’ll tell you that safety is their top priority. Despite these good intentions, our streets keep getting more deadly. To reverse a decades-long trend of steadily increasing pedestrian deaths, state DOTs and federal leaders will need to fundamentally shift their approach away from speed.

-

Why we need to prioritize safety over speed

Our roads have never been deadlier for people walking, biking, and rolling and the federal government and state DOTs are not doing enough. If we want to fix this, we have to acknowledge the fact that our roads are dangerous and finally make safety a real priority for road design, not just a sound bite.