When cities and states began shutting down in response to COVID-19, the financial impact to transit was swift and immense, but the immediate impacts only tell part of the story. Given the myriad ways that transit is funded around the country, the fiscal impacts of the pandemic will likely be varied and long-lasting. Congress and state legislatures should strive to find ways to adequately plan for and address those shortfalls in the long-term.

As businesses closed and non-essential workers followed the advice of health experts to stay home, transit lost a lot of riders and fares evaporated with them. On average, fares make up the single largest share (36 percent) of operating revenues for transit. But despite the fiscal cliff that a lack of riders presented, transit agencies actively began urging riders to stay home if possible—for the safety of riders and transit employees.

Combine the loss of fares with increased costs for cleaning (supplies, labor, and personal protective equipment) and it’s easy to see why transit agencies needed emergency operating funding.

But that’s only part of the story.

Public transportation is a public good and as such is funded by a variety of public revenues, like sales taxes, property taxes, and income/payroll taxes. Parking garages, advertising, and bonds are also sources of revenue for transit—both to operate and (especially in the case of bonds) for capital costs like new buses or a new rail line. All of those funding sources have been or will be adversely impacted by COVID-19 and the financial forecasts of transit agencies paint a grim picture.

In places where sales taxes make up a sizable share of funding (like Via in San Antonio, TX) the budget hole will appear fairly quickly. Sales dropped, taxes dropped, and funds stopped coming in. Those revenues will slowly begin to recover if and when businesses start to reopen and unemployment drops substantially—a hard thing to forecast in these unprecedented times. The CARES Act offered some support here, but more will be needed, especially as it becomes increasingly clear that the country’s economic recovery will not be as swift as it was assumed a few months ago.

“Projecting is tricky. There are so many variables and unknowns. It’s like throwing a dart at a fan,” says Karl Gnadt of the Champaign Urbana Urban Mass Transit District. “Our largest revenue stream is our state operating grant which is funded by state sales tax. Sales tax has tanked. The cuts will be significant and dramatic. The CARES Act is a band-aid over a broken bone.”

But the impact on property taxes and payroll taxes will be less immediate and potentially more troubling for that very reason. The impact of the pandemic on property taxes will likely be delayed by months or more given how they are collected. And budget holes from payroll or income taxes may not appear for close to two years from now.

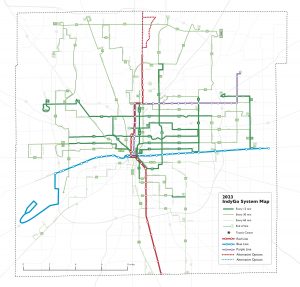

TriMet in Portland, OR gets about 60 percent of its operating revenue from payroll taxes, while IndyGo in Indianapolis, IN receives about a third of its operating revenues from payroll taxes and another third from property taxes. In many other communities, these taxes make up smaller but significant sources of funding. The conversation in Congress and statehouses around the country aren’t taking into account these looming fiscal crises.

IndyGo in particular is expecting a 50 percent drop in revenues that will suddenly appear two years from now. The financial forecast in other cities is likely just as stark, but these projections are getting very little attention.

“The unknown is how deep this recession will be and the impact to property values,” says Elizabeth Presutti, CEO of the Des Moines Area Regional Transit Authority. “We’ll see our impact 2-3 years down the road.”

Without action, service cuts are likely. Network expansions and improvements could be halted or abandoned. Old buses or trains might have to continue operating without funds to replace. Layoffs could come, further hampering the ability for transit to provide a useful public service. Degraded service will make it that much tougher for Americans hard-hit by the recession to get to jobs and services right when they most need an affordable option.

As the service suffers, ridership will be harder and harder to attract and our communities will pay the price with worsened traffic and pollution.

As Congress and state legislatures consider additional measures to help communities recover, the long-term transit impacts should be considered as well.

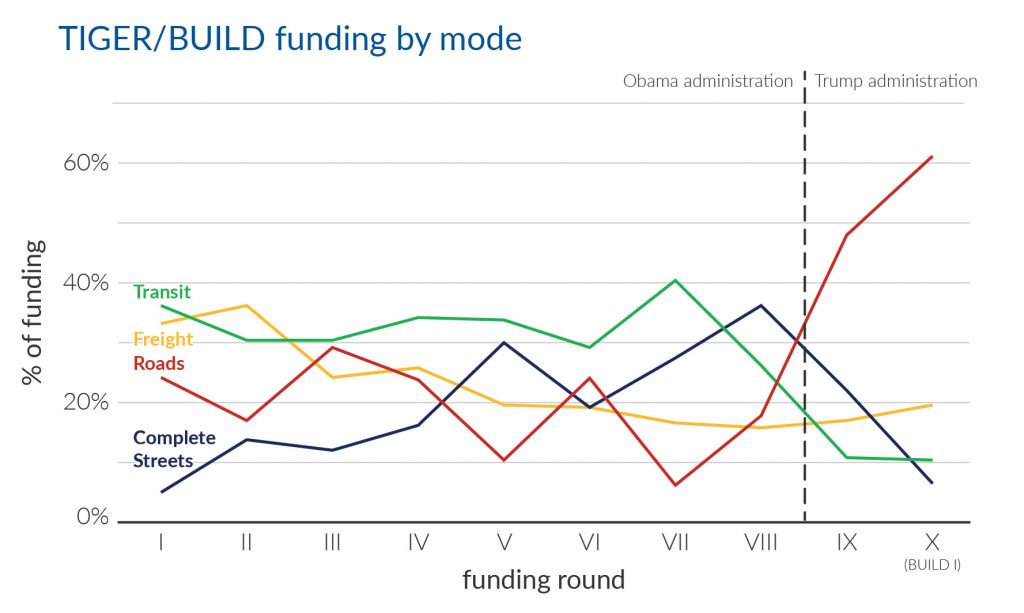

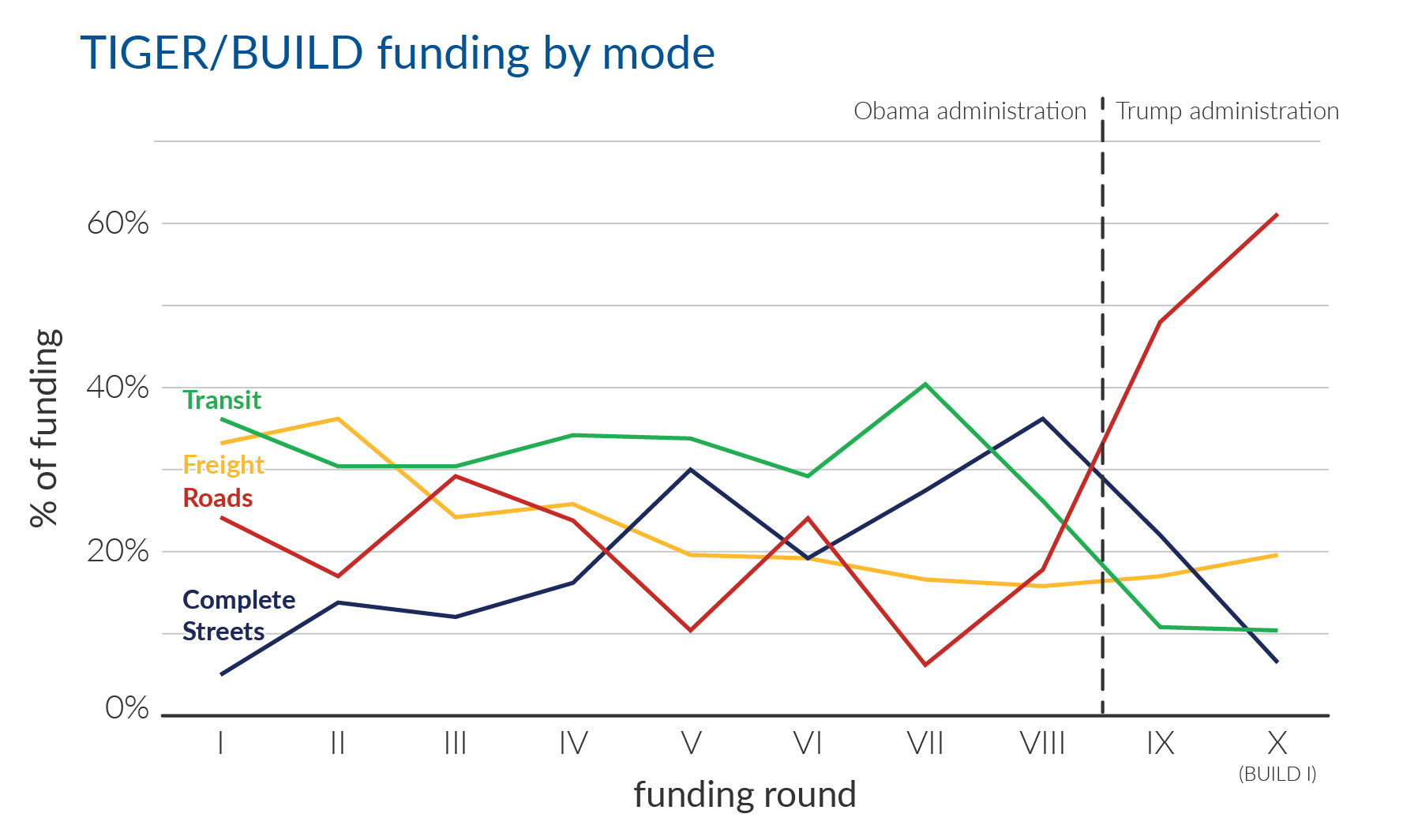

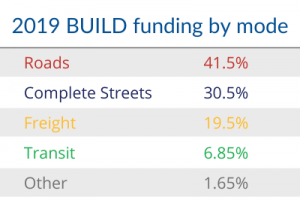

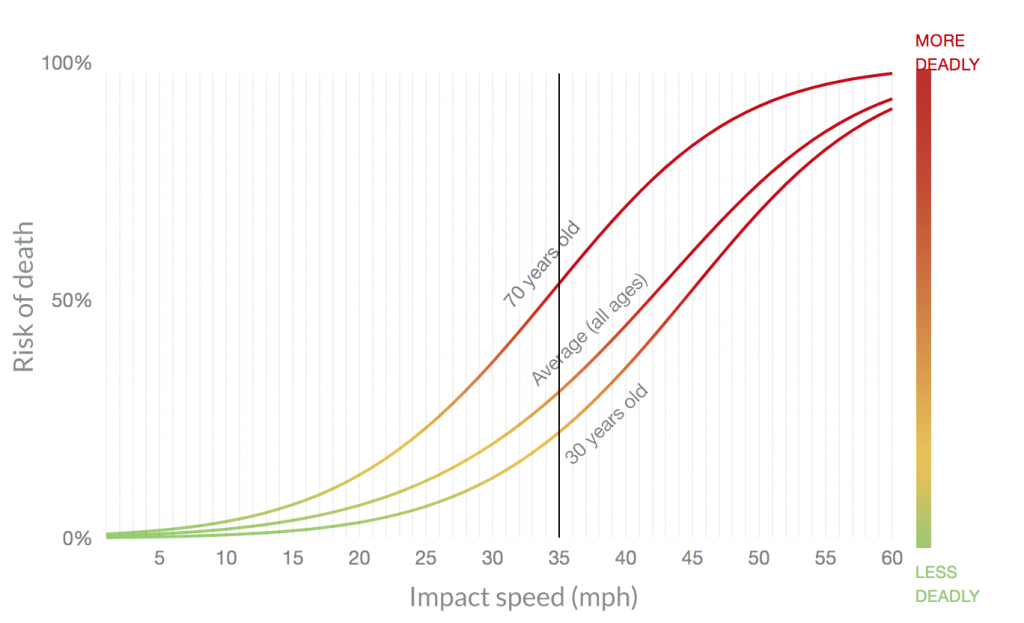

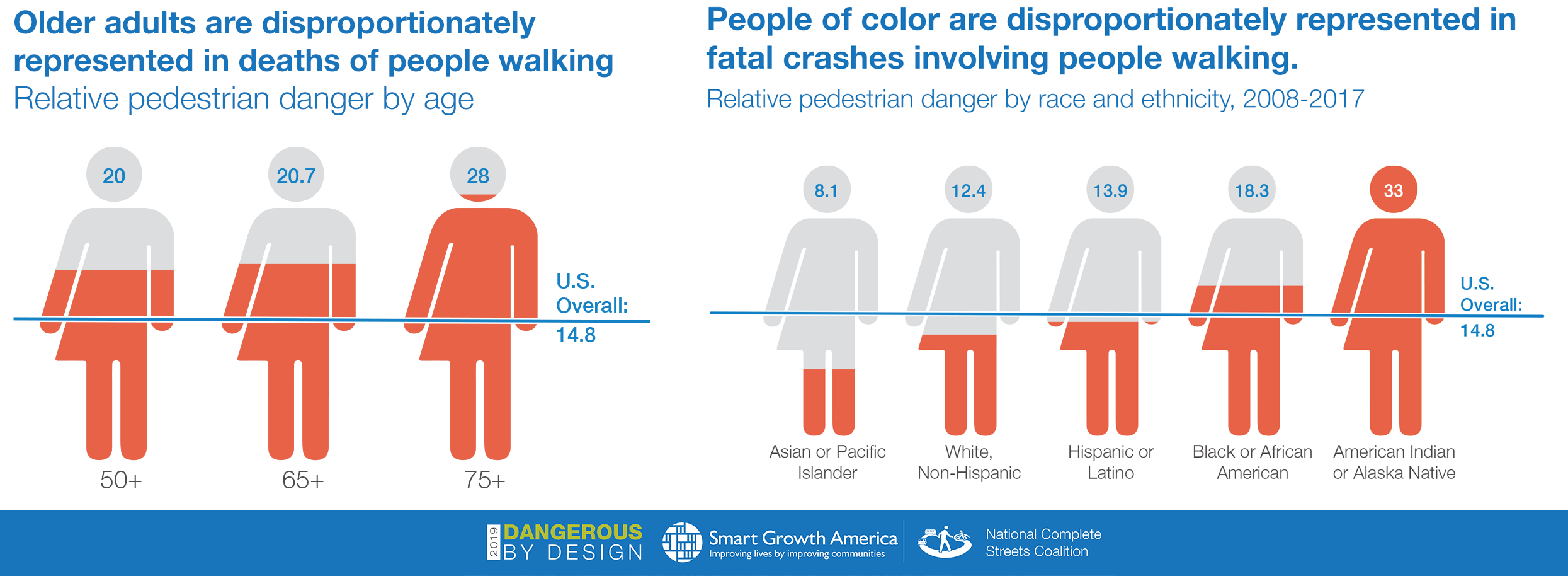

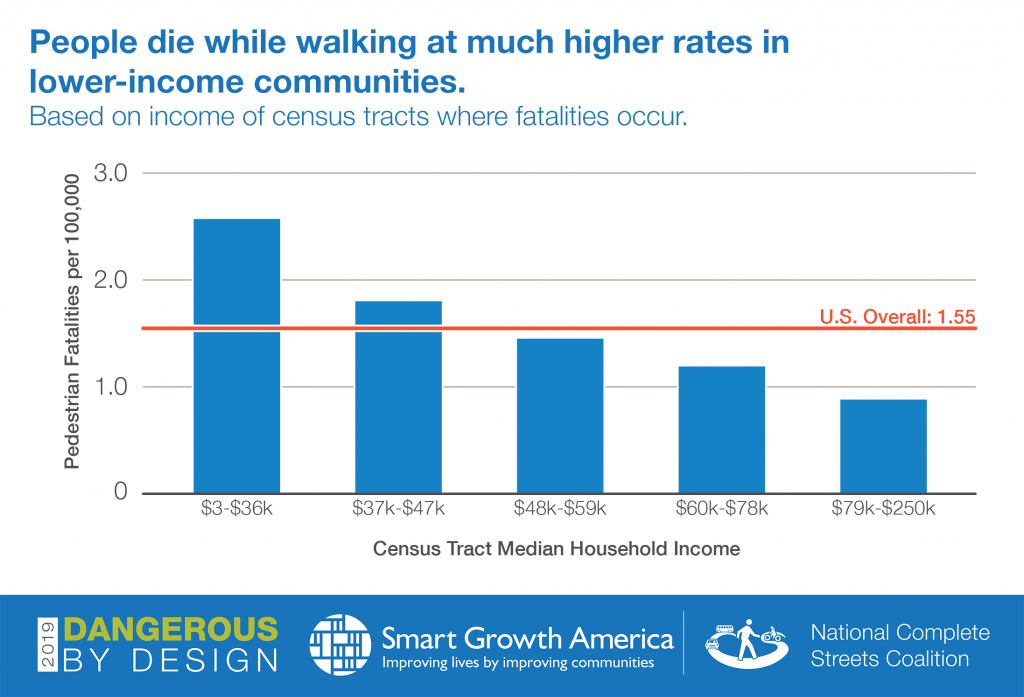

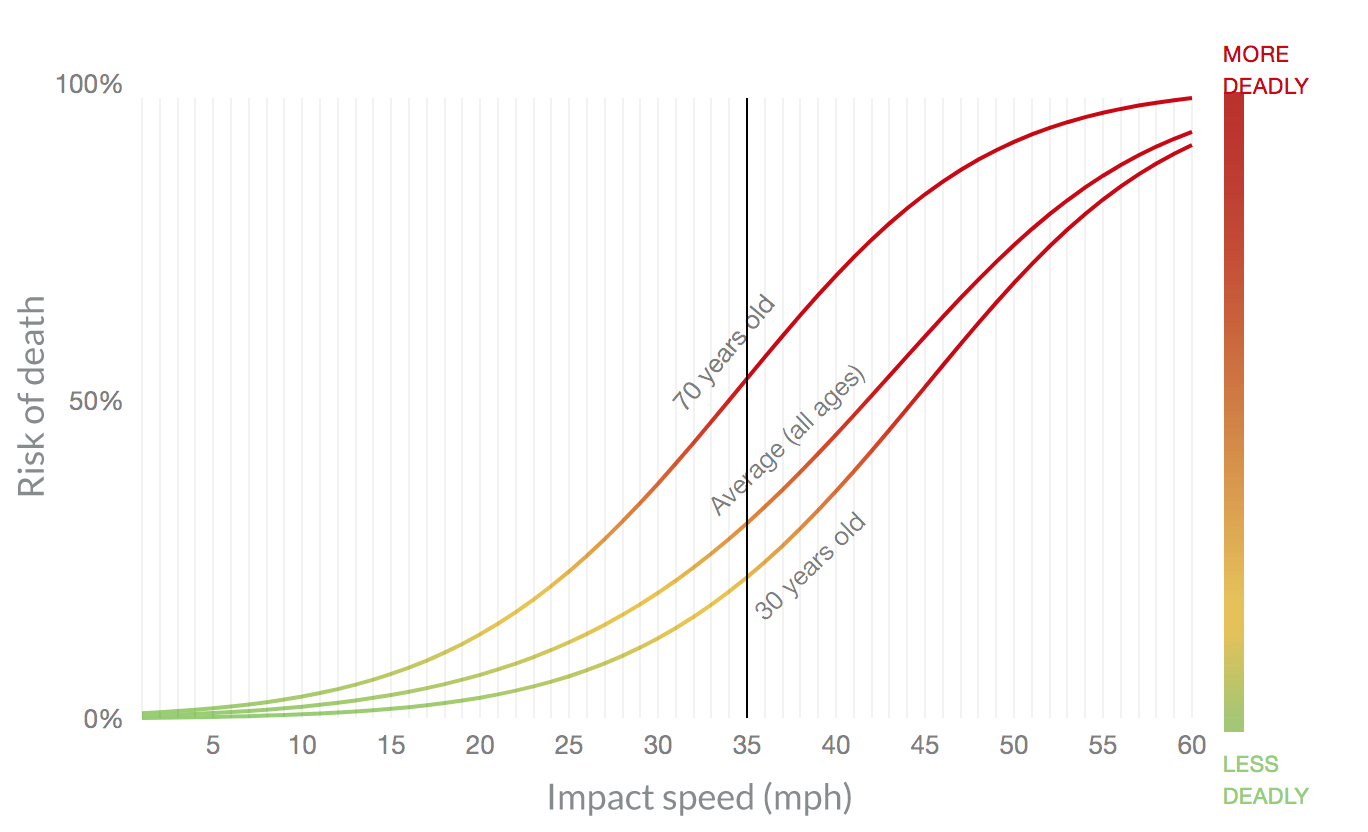

But there is a bit of a silver lining: Complete Streets & other multimodal projects racked up almost a third of the BUILD funding, the highest percentage such projects have received under the Trump administration. This is also particularly notable given the worrying rise in pedestrian and bicycle fatalities across the country, attributable in large part to the lack of safe infrastructure on our roadways for people without cars.

But there is a bit of a silver lining: Complete Streets & other multimodal projects racked up almost a third of the BUILD funding, the highest percentage such projects have received under the Trump administration. This is also particularly notable given the worrying rise in pedestrian and bicycle fatalities across the country, attributable in large part to the lack of safe infrastructure on our roadways for people without cars.

Last week, Representatives Chuy García (IL-4) and Ayanna Pressley (MA-7) co-hosted a briefing on Capitol Hill on the nexus of transportation and the climate crisis and announced the imminent launch of a caucus focused on creating a new vision for our transportation system.

Last week, Representatives Chuy García (IL-4) and Ayanna Pressley (MA-7) co-hosted a briefing on Capitol Hill on the nexus of transportation and the climate crisis and announced the imminent launch of a caucus focused on creating a new vision for our transportation system.