Electric vehicles, while vital for reducing emissions and meeting our long-term emissions reduction goals, are not a good strategy for improving existing inequities in transportation. But there are specific things we can and should do to make this transition more equitable than it otherwise would be.

Yesterday, in part one of this post, we chronicled why it’s going to be difficult or impossible for electric vehicle adoption to be a major force for improving equity, but that doesn’t mean we can’t make it as equitable as possible. Here are some ideas for how:

E-bike incentives and infrastructure

Most daily trips on average are short, but many can still be just outside of the realm of capability for a lot of people to take by walking or biking, especially in hot climates that make it difficult. E-bikes are a game changing option for many people, increasing the ease, range, and comfort of biking trips while still delivering the public health, space-efficiency, and zero-emission benefits of bikes. They are way cheaper than electric cars and therefore cheaper to subsidize. Perhaps this is why e-bike sales have more-than doubled last year, and why e-bikes are projected to out-sell electric cars globally in the coming decade. For the cost of the incentive for a new electric car, you could outright buy an electric bike for someone. All this means we can help get more e-bikes into the hands of people for whom it can make a real impact on their access to opportunity, and reduce emissions. The e-bike incentive in the Build Back Better Act is a great start. To get the most out of this new option, we also need to invest in infrastructure where e-bike riders feel safe.

Fleet conversions

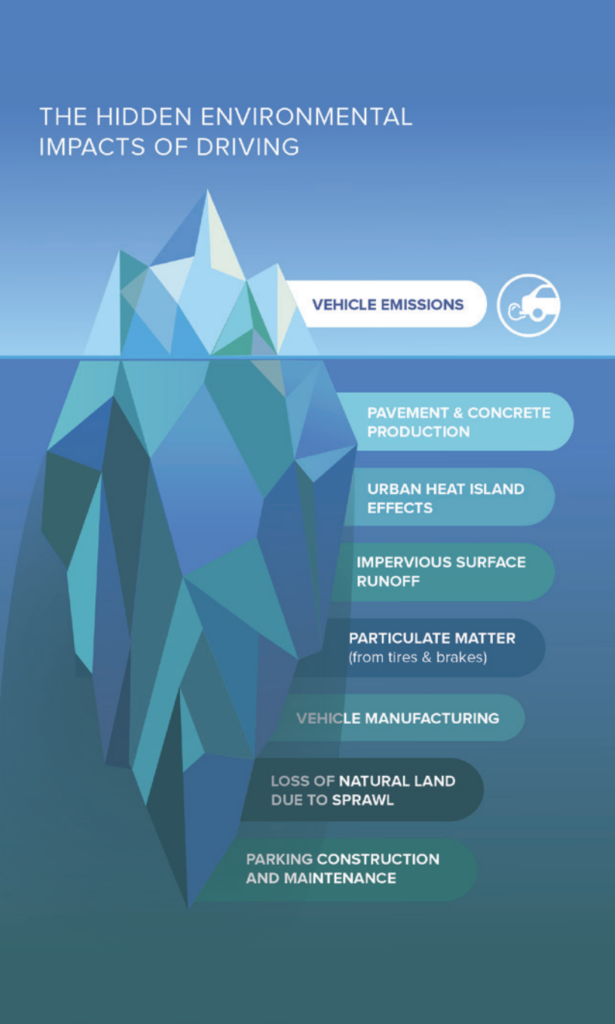

Cars for individual drivers sit parked most of the time, using up valuable space for parking—and not presenting as big and quick an emissions reduction. Transitioning institutional fleets to electric has a good return on investment, whether they are for carshare fleets that give low-car households access to a car when they need it, rental fleets that quickly rack up mileage, business fleets that are used by company personnel throughout the day, or diesel trucks and buses that produce more pollution. Incentives can also target non-profits that deliver valuable community services. We should also consider targeting high-polluting areas for specific and notable impacts, for example prioritizing truck conversions at ports adjacent to neighborhoods that bear the brunt of port pollution. If we’re going to subsidize electric vehicles, focusing on fleets first can build the EV market while delivering the most bang-for-the-buck on pollution reduction and benefits to impacted communities.

Deploying the right charging strategy in denser urban environments

One of the benefits of EVs for consumers is charging at home. If you plug in your car overnight, you never have to go to a charging station unless you’re taking a trip that exceeds your car’s range. Your car has a “full tank” every morning. But that only works if you have a dedicated parking space with access to your own electricity. In denser urban environments, many people lack a driveway or garage to charge an EV. Historically excluded communities are much less likely to have the kind of dedicated parking where overnight charging from your own outlet is possible.

Photo on left courtesy of @kiel_by_bike

We’ll need a comprehensive set of solutions to address this that won’t all fit in this blog post (and no one has all the answers for that yet). But there are two areas to focus on. First, we need building codes that require charging access in multifamily housing parking AND bike parking that accommodates level entry and charging for e-bikes that are much heavier. No one wants to lug a heavy e-bike up and down stairs. Second, we need a comprehensive policy on curbside charging that considers the vast complexity of managing curb space, which is something we have written about before, including:

- Prioritizing carshare

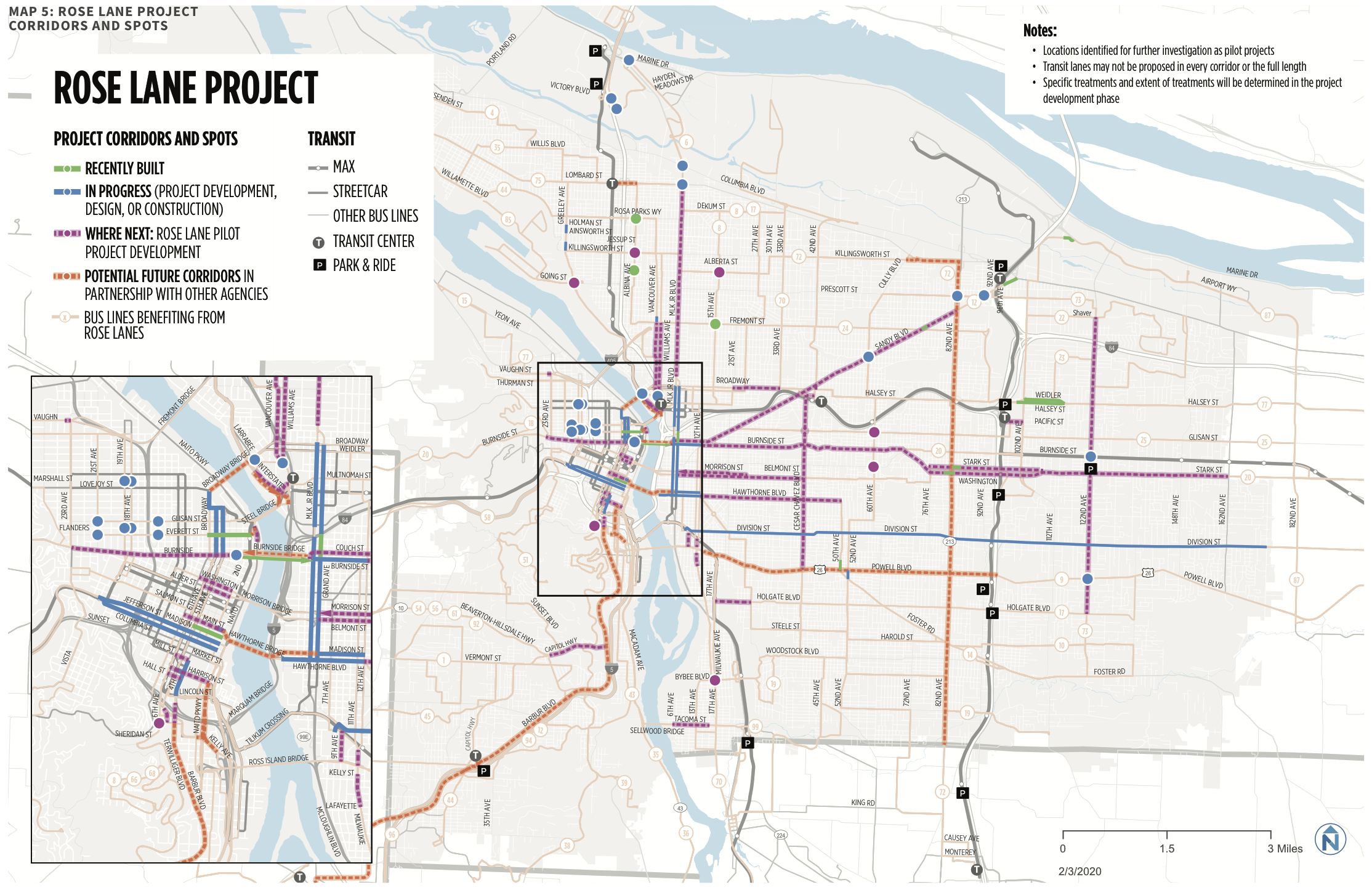

- Protecting current and future bike and bus lanes

- Integrating chargers with public space and ensuring an uncluttered pedestrian environment including quality Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) access

- Ensuring deployment in historically excluded neighborhoods

Phasing out ICE vehicles through legislation

Much of the discussion around getting EVs into the hands of consumers has been around incentives and subsidies. This is an approach to benefit industry and wealthier new-car buyers. At this point, every major car company has electric models coming to the market soon. If we need to transition the fleet to electric, rather than offer subsidies to buyers who least need them, eventually we’ll need to consider both carrots and sticks. Why not follow the lead of California, which is moving to ban the sale of gas-powered vehicles by 2035, and set a date to phase out new internal combustion engine (ICE) cars by a certain date a few years from now?

Workforce training and support

As with any major change in how we do things, some jobs will disappear and others will be created. We’ll need programs to support mechanics and other workers impacted by the EV transition. For example, programs supporting the EV transition should incorporate training for mechanics who work on cars, trucks and buses so they can transition to working on electric vehicles. Likewise, we also need to provide workforce education, training, and certification for electricians installing and maintaining EV charging infrastructure. Training for new manufacturing jobs should target deployment of jobs and job training programs so that frontline communities are prioritized and have an opportunity to benefit from manufacturing jobs. Finally, policies should require prevailing wages for jobs installing publicly funded charging infrastructure and/or union representation for publicly subsidized manufacturing jobs. The Coalition Helping America Rebuild and Go Electric (CHARGE), with which we’ve worked this past year, has done a great job thinking about workforce considerations as part of their policy recommendations.

EV advocates can and should do what they can to address equity in the EV transition, but they need to recognize that the strategies for doing this are by their very nature afterthoughts. EVs are a GHG reduction strategy, not an equity strategy. Investing in transportation options like public transit, walking and biking, and meeting the demand for new (attainable) housing in locations where people naturally drive less is the way to truly address transportation equity as part of an overall GHG reduction strategy.

If you’re interested in digging deeper into equity and electrification, EVNoire and Forth, two partners we work with in the EV space, are hosting the E-Mobility Diversity Equity and Inclusion Conference next Wednesday and Thursday, November 17 – 18.