In November 2020, we sent the incoming Biden administration a memo outlining immediate and longer-term actions we urged the new president to initiate. Four years later, while modest progress has been made on some, it’s hard to say that the transportation system or the most important outcomes by which we should evaluate it are significantly better or different than four years ago.

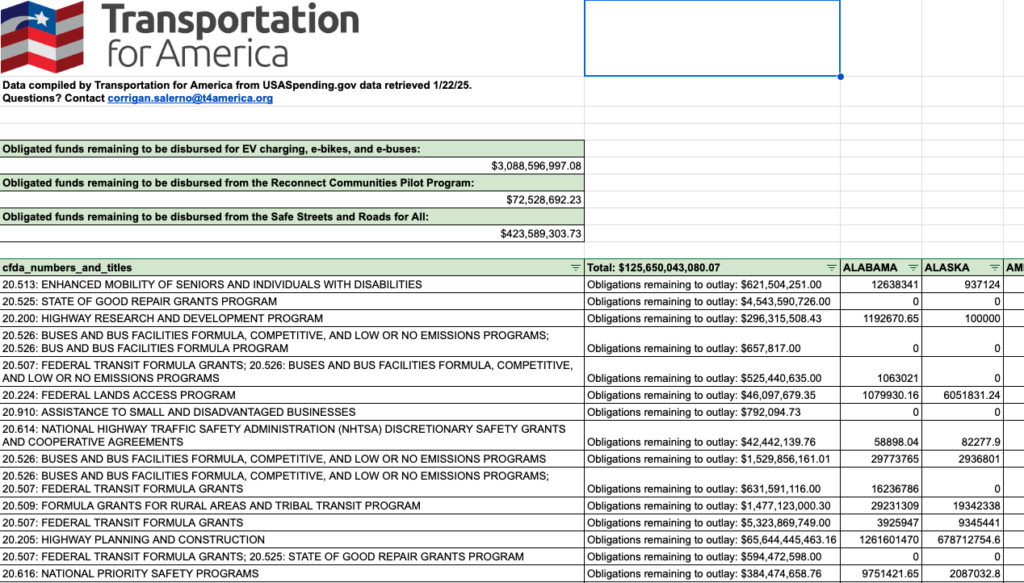

As the Biden administration comes to a close, it’s time to take stock of what President Biden and his team accomplished. (You can read our recaps of the Biden administration’s progress after their first, second, and third years.) There are certainly some tangible wins and progress to point to, like new programs focused on climate change and electrification, USDOT advancing smarter projects with their discretionary programs compared to the previous four years, and some positive administrative changes. There was also a massive infrastructure bill that did have some notable but small wins, though they all came alongside the IIJA’s historic amount of funding. Overall, the status quo on transportation that was in place when the Biden administration arrived is largely unchanged, though it is far better funded.

Before we get into the good and the incomplete, let’s look at the table of specific requests we made in November 2020.

[table “160” not found /]

In truth, our hope was that many of these requests could be tackled in the first hundred days or over the first year. We were hoping to be able to check things off this list and add more ambitious tasks for the intervening years as time went by. But as you can see, four years later, most of the initial list is either undone or incomplete.

Beyond this list, it’s hard to say that the most important measurable outcomes for transportation overall—safety, state of repair, emissions, access to destinations, delay or congestion—are significantly better today than four years ago or are on track to improve significantly in another four or eight years, even after the IIJA’s $643 billion is completely exhausted. The IIJA overall is advancing projects that will increase emissions. Many of the new grant programs could either go dormant, be defunded by Congress, or be used by Trump’s USDOT to fund radically different kinds of projects—like when President Obama turned grant programs like TIGER over to the Trump admin eight years ago.

While Congress writes the laws that determine where most transportation dollars go, USDOT did not take full advantage of the tools at its disposal to make the kind of binding, institutional, structural changes that will move the needle and can’t be easily undone by a future administration.

The good:

Greenhouse gas rule

Resurrected from the Obama administration, a measure to assess the greenhouse gases coming from transportation projects was introduced in 2022 and finalized in 2023 (only to be ultimately overturned after challenges in the courts and Congress). While the administration certainly deserves credit for this attempt, they did slow-walk the development and implementation of the rule primarily due to fear that the opposition would block it versus swiftly developing and implementing the program and navigating opposition along the way.

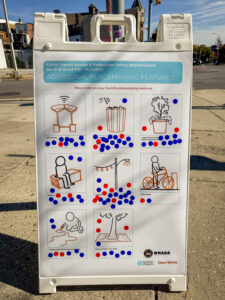

Small steps for safety

Steps were taken to elevate the conversation on roadway safety as a national crisis and the need to fundamentally change the trajectory of the United States. This included the development of a National Roadway Safety Strategy, an overhaul of the Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices, and new vehicle safety rules aimed at addressing the safety of all users of our streets. However, those changes are modest and unlikely to be enough to overcome the entrenched auto-dominated culture.

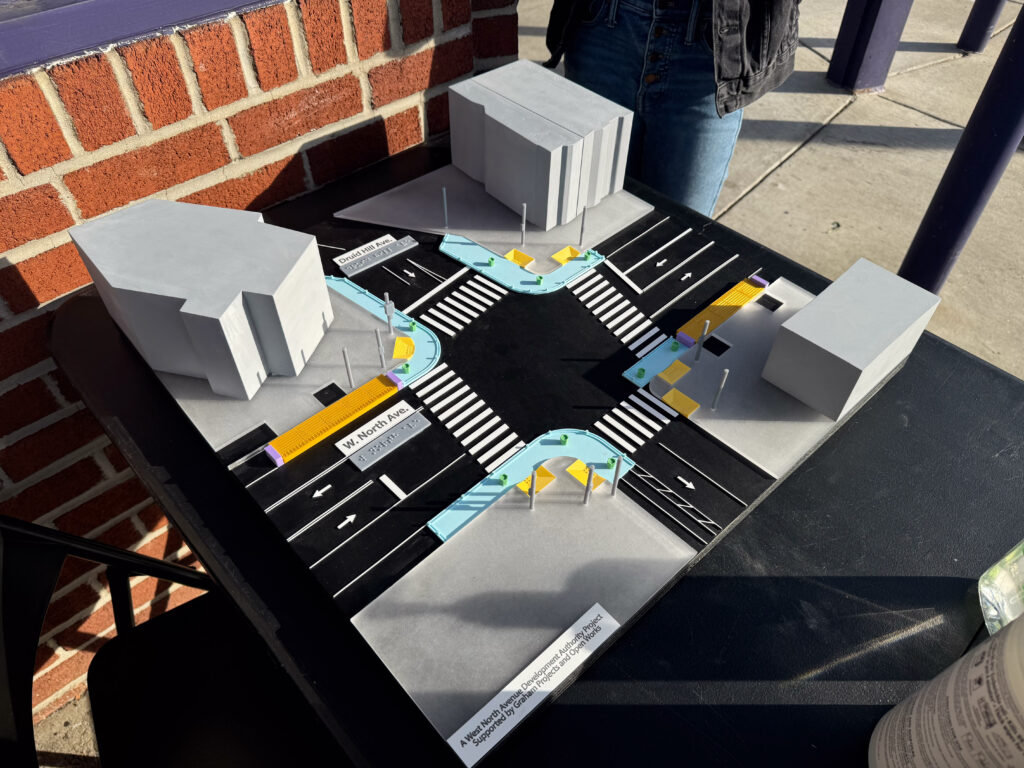

Important though limited steps on reconnecting communities

One of the biggest highlights of the IIJA was the new Reconnecting Communities program, which funds projects that seek to repair past damage from infrastructure projects, such as divisive highways. While USDOT can only choose from the projects that do apply, it’s fair to say that their track record has been mixed at best. As America Walks noted in 2024, more than $1 billion of the 2024 awards is going toward a) accommodating people while preserving damaging roads or b) mitigating some of the damage of actively expanding highways. Trying to mitigate brand new damage to Portland from expanding Interstate 5 is not what this small program focused on repairing past damage should be for. USDOT should prioritize more inspirational, best-in-class examples for other states and cities to see what’s possible, like Syracuse removing I-81 and replacing it with a street grid.

Ample offerings for technical assistance

The administration did create numerous enhanced technical support offerings, such as the Thriving Communities program, which helps local communities and stakeholders access and navigate federal funding programs, and the (long-delayed) Reconnecting Communities Institute, designed to help communities plan and advance Reconnecting Communities projects. These new programs (and others like them) have been a smart way to help communities navigate the sea of new competitive grant programs created in IIJA.

Incomplete at best, bad at worst

The IIJA will increase emissions overall and fail to move the needle on other measurable outcomes. It should not be viewed as a major accomplishment.

The Biden administration will be leaving office continuing to hail the 2021 infrastructure law (IIJA) as “once in a generation,” “climate-friendly” legislation that will transform the status quo on transportation. Unfortunately, both the IIJA as written and the Biden administration’s implementation of it have been a boulevard of broken dreams. It was always unwise for this administration to sell the IIJA’s massive climate, equity, or state of repair benefits when those benefits have to be delivered by states that don’t share the administration’s goals or preferred outcomes.

Equity investment outcomes muddled

Equity was a core component for the Biden administration, which introduced the Justice40 executive order aimed at ensuring 40 percent of federal funds flowed to and benefited historically marginalized communities. However, it has yet to be seen whether this policy initiative truly targeted benefits towards marginalized communities or just directed funding to areas and projects that just happen to also have a notable marginalized population. The future of such initiatives is in doubt due both to the challenges they’ve had in implementing Justice40 during their time and the fact that Justice 40 can be easily undone by future executive orders.

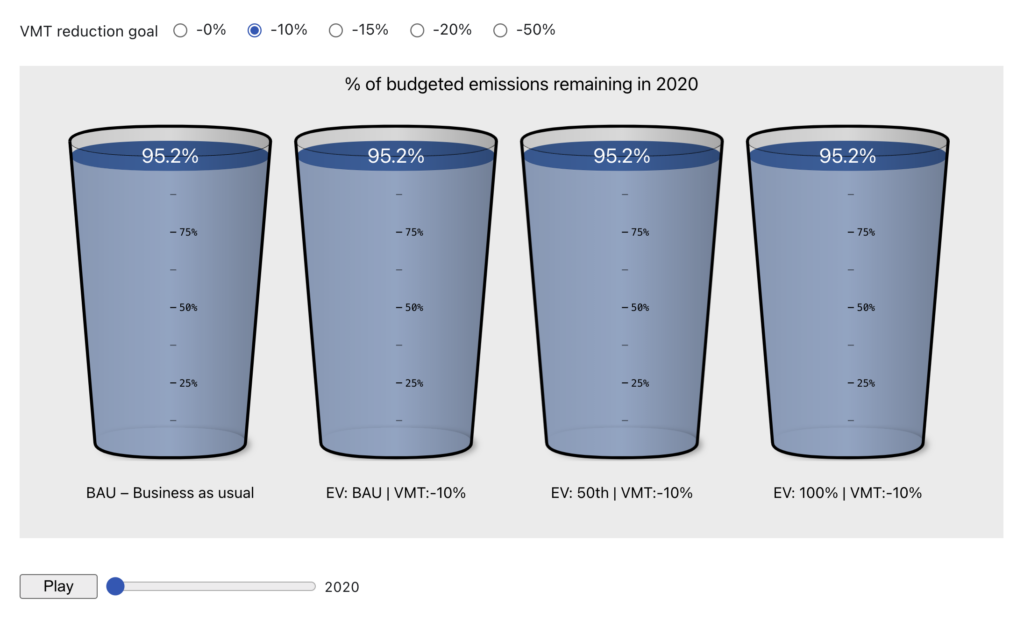

All-in on electrification only

The Biden administration put all their eggs in the single basket of electrification to tackle transportation emissions. The flaws in that strategy are becoming more obvious by the day, with President Trump and Speaker Johnson signaling their intent to claw back money for new charging infrastructure and repeal mandates requiring more electric vehicles in the future. Transportation electrification is important for decarbonizing transportation, but it’s only one piece of the puzzle. The administration’s emphasis on climate change was far out of sync with the reality of how IIJA funding was being used: many states using their formula funds to expand highways and spur more vehicle miles traveled (VMT). Even discretionary grants that USDOT had control over were also still contributing to more VMT. Meanwhile, under the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program, onerous requirements directed funds toward highway-oriented development and away from communities, helping to undercut the economic development benefits and potential rural support for a program almost certainly to be targeted for cuts or elimination by President Trump.

Failure to modernize street design guidelines

After more than a decade of waiting for a promised update, the release of the most recent edition of the Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices promised to shake up roadway design standards. But as we noted upon release, the cautious and overall incremental update “falls short of the kind of major paradigm shift required to protect vulnerable users at a time when the United States leads the developed world in roadway fatalities.” Future updates may still happen, but this administration failed to take advantage of the potential of long-term, structural changes like these, perhaps not grasping the long-term impacts.

No changes to traffic models and measures

While Congress sets the policy and states have enormous flexibility for spending transportation dollars, USDOT and FHWA determine what models and measures states can use in conceiving and advancing new roadway projects. On day one, we hoped that USDOT would make moves to require the measurement of “induced demand” and use their bully pulpit to kickstart a long overdue conversation about the inaccuracies of current traffic models, perhaps starting to compare past projections with actual outcomes. USDOT could have delivered guidance on measuring time savings benefits, emissions reductions, and transit access to ensure that projects meant to achieve these goals are set up to succeed. Unfortunately, there was no real movement on the small but powerful changes that would outlast this administration.

Amtrak oversight and staffing

Appointing a full Amtrak board that’s representative of the people the passenger rail system serves would have been a notable, easy win for the administration. But rather puzzlingly, “Amtrak Joe” took a year to nominate anyone to the board. The administration and Congress have only recently finally filled all board slots, but as composed, it still doesn’t fully represent the full network that Amtrak serves. The overall lack of oversight has led to declining service reliability and customer satisfaction, further hurting Amtrak’s reputation with the public and Congress. Further, at a time when there is historic funding for passenger rail, the funding is not being spent due to slow movement in the program and a failure to get sufficient staff in place at the Federal Railroad Administration quickly after the IIJA’s passage to create and implement these new programs.

Closing reflections

The question for an incoming administration hoping to have an impact should not just be “How can we steer the money we control toward good projects?” but instead, “What changes can we institutionalize to disrupt the status quo and produce better results for years to come after we’re gone?” Modest progress has undoubtedly been made during Biden’s time in office, but so much of it is of the first variety—temporary and potentially undone by any future administration. This administration also spent an inordinate amount of time soliciting feedback and research before taking any action on rulemakings that help interpret laws like the IIJA—and, in many cases, never acted on the comments at all. And if the cost of creating valuable but small new climate-focused programs (a la the IIJA) is doubling the size of the blank check programs that are damaging the climate, that’s a bad deal for everyone except concrete and asphalt contractors.

For the incoming Trump administration, we’re working on a to-do list for their first 100 days and the following years to reduce wasting limited resources and ensure that every dollar works towards advancing safety, economic opportunities, and better state of repair.