What happened to U.S. passenger rail?

Almost a century ago, the railroads were the economic engine of the country, spurring the transportation of both goods and people over long distances. Now, the American railroad system is merely a specter of its former self. How did the United States devolve from an expanded passenger rail network to the system we have today?

In recognition of recent progress for passenger service in the Coastal South, we’re releasing a four-part series exploring how unified regional and national approaches, supported by local advocacy and sound policy, can help create a successful passenger rail network. This is part one of the series, written by Mehr Mukhtar and London Weier. Read part two on building momentum for change, part three on converting support into action, and part four on next steps for a national network.

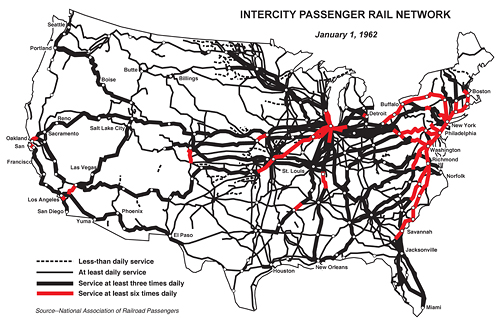

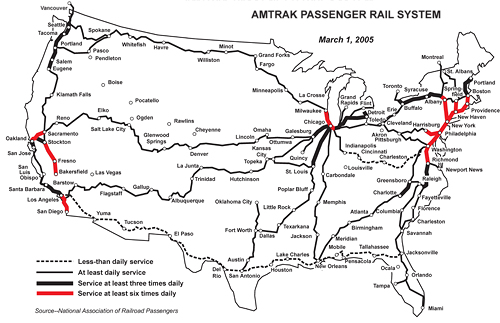

The Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970 created the National Passenger Railroad Corporation (Amtrak as we know it today). The advent of the automobile, creation of the Interstate Highway System, and a boom in air travel all diverted passengers away from rail. Railroads began losing out on passengers, and in their desire to increase profits, they started viewing their requirement to maintain passenger railroads as a costly financial burden. Creating a dedicated entity to serve passenger rail was seen as the solution to shifting the burden of passenger railroads away from freight railroads.

The mission of Amtrak at its inception, to maintain a national passenger rail network, is a far cry from the current state of the corporation. This is largely due to a failure in government funding, as policymakers continue to criticize Amtrak for a lack of profits, even as a lack of funding diminishes the service. In 1995, Amtrak faced severe budget cuts by the federal government, forcing suspensions and reduced service across the country.

In most of the country, passenger service decreased from 7 days per week to only 3 days per week and some routes were permanently eliminated, devastating the frequency of the service and its reliability as a mode of commuting. This had particularly far-reaching consequences for smaller towns and cities that suddenly became disconnected from their passenger rail routes.

Despite this setback, local leaders coalesced to press Amtrak and Congress to restore many of these reductions in service. Congress responded by creating an entirely new Amtrak Board of Directors, and under new management, Amtrak made great strides in the Northeast Corridor with the rollout of Acela, their first high-speed rail, in 2000. They accomplished this all while improving long distance service and developing state supported service. These improvements were short-lived, however. Changing leadership of the board and executive staff led to decisions focused on the Northeast Corridor to the detriment of the national system. This deficiency of investments and oversight outside of the corridor stifled expansion in the rest of the nation.

In the Coastal South, as in much of the United States, this trend ultimately resulted in a passenger rail system that was failing to prioritize connectivity and meet the needs of the public. Hurricane Katrina was the final nail in the coffin.

Disaster strikes

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast of the United States, causing thousands of deaths and over $108 billion in property damage. Among the damage caused by the storm was considerable destruction of critical rail infrastructure, especially on the line between New Orleans, Louisiana (LA) and Mobile, Alabama (AL).

In the days immediately before and after the storm, all Amtrak service through New Orleans was halted. Today, three long distance trains depart from New Orleans Union Passenger Terminal, the City of New Orleans (service between New Orleans and Chicago), the Crescent (service between New Orleans and New York), and the Sunset Limited (service between New Orleans and Los Angeles).

Although the City of New Orleans and the Crescent returned in full swing about one month after Katrina made landfall, the Sunset Limited service was permanently changed. Prior to Katrina, Sunset Limited connected communities from coast to coast, running from Los Angeles to Orlando, Florida; however, since Katrina, the train reaches its final eastward destination in New Orleans.

The brunt of track damage occurred on the eastward bound sections of track connecting New Orleans to Mobile, an essential connection to continue Sunset Limited service to Orlando. Along this route, Amtrak passenger trains shared track belonging to freight companies CSX Transportation, Norfolk Southern (NS), and Union Pacific (UP). CSX took the brunt of storm damage and needed to restore five bridges and 40 miles of track that were completely washed out in the wake of Katrina. Norfolk Southern and Union Pacific lines also experienced considerable bridge damage and track repairs, including the need to restore felled power lines. Though freight rail lines took four months to repair, tracks shared by Amtrak (which were the responsibility of freight railroads to restore) took six months to recover.

In the almost two decades since Katrina made landfall, passenger rail lines leading eastward from New Orleans have not been restored. Post-hurricane rail restoration left this line out of the picture, an oversight that members of the impacted communities would fight for years to amend.

The loss of Gulf Coast service after Katrina had a particularly devastating impact on communities in the region, but the decline of passenger service in the South was also reflective of a larger disinvestment in passenger rail in every part of the country, particularly outside of the Northeast Corridor.

These lessons from the past can serve as a blueprint for the future of nationwide passenger rail that we are aspiring towards. New funding mechanisms and policy developments, such as the IIJA, capture the efforts to revive the historic role that passenger railroads have played in the country. Through decades-long advocacy with passenger rail groups across the country, Transportation for America has demonstrated that good policy, combined with the knowledge and expertise of dedicated advocates, can build momentum for improved service to reverse the deterioration our passenger rail system has witnessed. We’ll explain how in the next three parts of our series. Stay tuned!