Follow the money: Where does your state stack up on supporting transit?

Even though transit service is a localized experience, the state you live in actually has a massive impact on your access to frequent, reliable transit. As with interstates, ports, or other vital parts of a state’s transportation network, state governments have a major role in supporting the planning, operations, and maintenance of public transportation service. But the financial commitment to transit varies widely from state to state.

In partnership with the National Campaign for Transit Justice, we assessed the quality of transit support and availability across all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. We’ll unpack our four criteria in a series of blog posts. This first post focuses on the dollars and cents: transit spending and restrictions on state tax dollars.

At a time when transit agencies are facing heavy financial stress, state support can be a key source of funding that allows transit to continue delivering reliable service. Most large transit systems, many of which are vital for supporting the largest regional economy in a state, operate with some level of support from their state. But that’s not always the case. There are statewide policies that impact a state’s financial commitment to transit, which can range from robust support down to almost nothing.

Transit agencies across the nation are nearing a fiscal cliff in 2023 as Covid-era relief packages expire. Click here to learn more.

Transit spending

If you’ve ever wanted to know what your state’s priorities are, take a look at the budget. That’s one of the first places we looked to assess state support for transit.

The 2021 infrastructure law increased federal transit spending, but in almost every case (with the exception of small agencies), these funds are not permitted to be used on operations, which means they don’t cover expenses like bus drivers’ salaries or bus maintenance. These expenses account for two-thirds of transit agencies’ total expenses, and without federal support, the burden of this funding can only realistically come from a few sources: state funding, local funding, and farebox revenue. The amount of state funding can have a major impact on the reach and quality of transit, especially in rural areas that don’t have as much local funding to supplement state dollars.

Click here to learn how transit spending on operations impacts local driving habits.

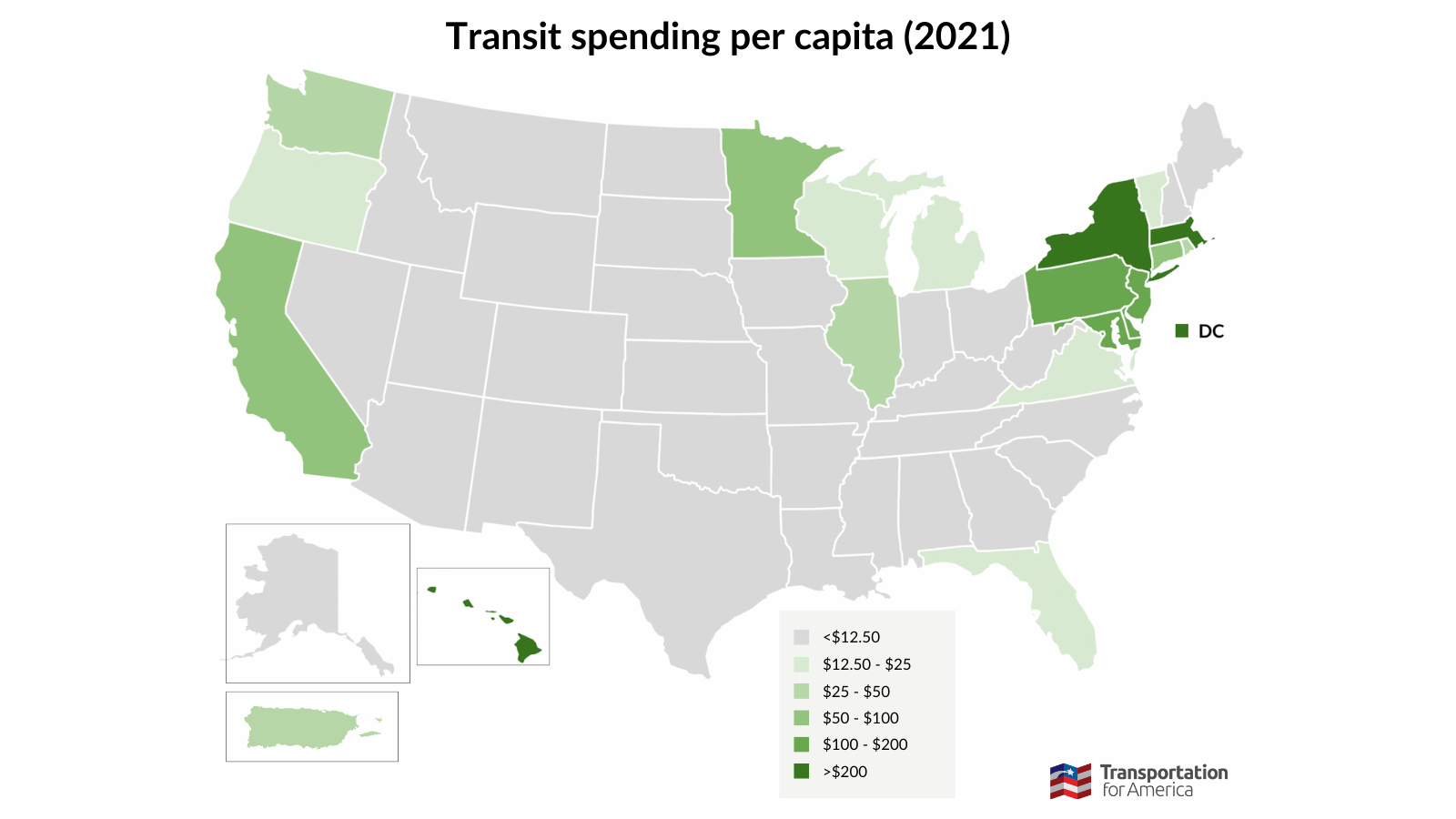

In the first graphic below, transit spending refers to each state’s total spending on public transportation in 2021—adjusted to per person rates to fairly compare states of varying size. We identified six bands of state transit spending per person:

- Less than $12

- $12.50-$25

- $25-$50

- $50-$100

- $100-$200

- More than $200

To see where your state lands, take a look at the figure below.

While the map above shows each state’s most current spending levels (from 2021) on public transit, it’s not a full picture. Annual transit spending is also volatile, subject each year to the whims of state legislators, so these numbers from 2021 could look very different today. To get a stronger sense of long-term transit funding, we had to take a look at one of the frequent key sources—gas taxes.

State restrictions on gas tax revenue

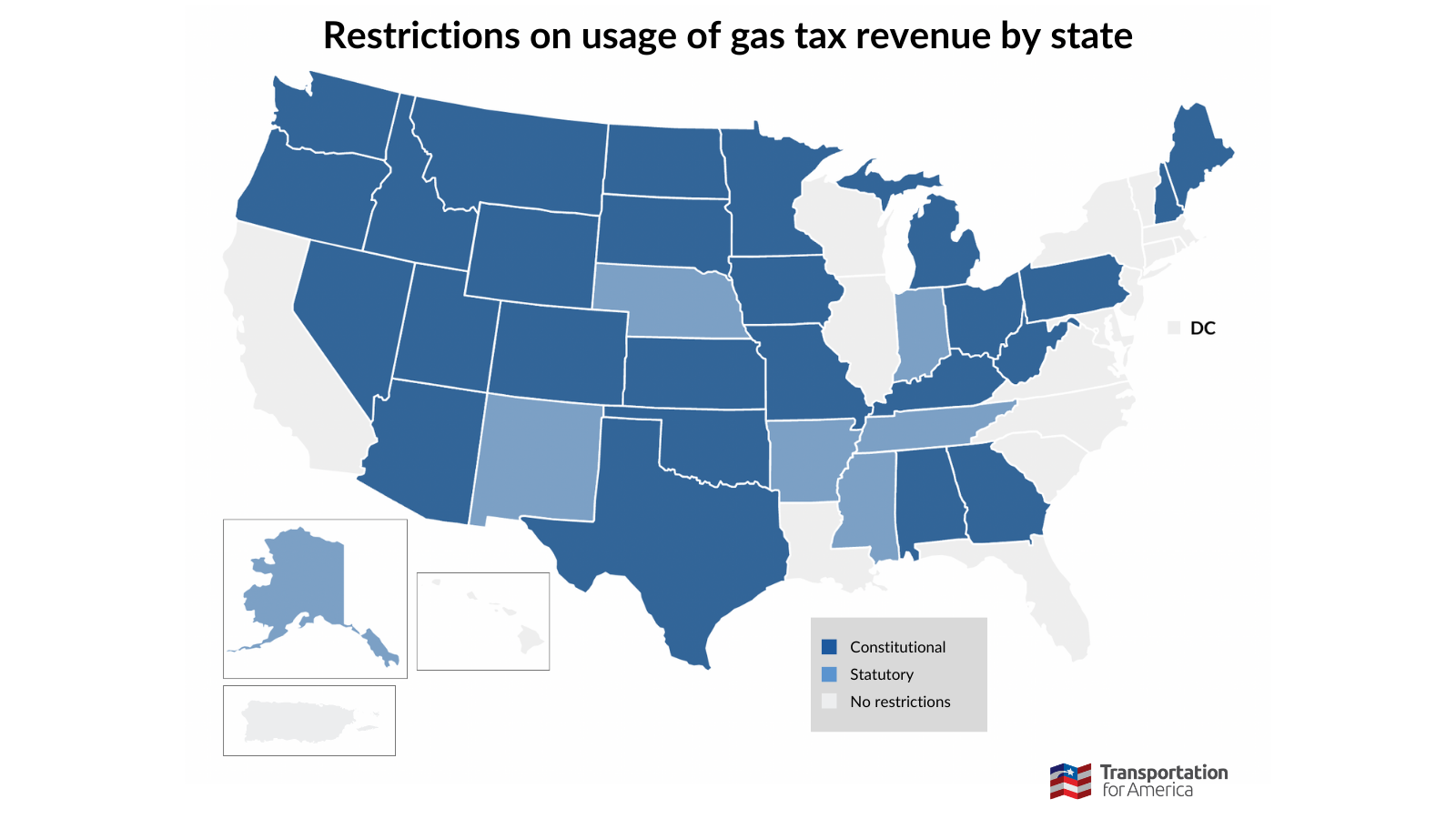

Gas taxes are the taxes you pay every time you fill up a tank, and they’re the bedrock revenue stream for most states’ transportation systems. In fact, this is how we fund transit capital improvements nationally, by devoting a small share of the 18.4¢-per-gallon federal gas tax to a trust fund for transit. Yet in many states, it’s illegal to use state gas taxes for public transit.

Restrictions on gas tax revenue create a counterintuitive cycle, where all gas tax funding goes only toward building more roads, resulting in people having to drive more, which means more gas sold, which means more money spent on only new roads and no other travel options—leading to more driving and more spending. Without the reliable source of funding fuel taxes would provide, many transit agencies have had to rely on sales taxes, which are an incredibly volatile funding source subject to the swings of the economy. As a result, transit agencies can be forced to raise fares or cut service to stay afloat.

Gas tax restrictions can come from state statutes or state constitutions. Statutes are laws that can be written, passed, and repealed by state legislators. On the other hand, to repeal any law in a state constitution, an amendment needs to be passed. It is more difficult to pass a constitutional amendment than to repeal a statute.

In seven states, gas tax revenue is restricted by state statutes. Though these prohibitions can be a frustrating roadblock for advocates and transit agencies, they can be repealed. In the figure below, these states are shown in medium blue.

23 other states have a clause in their state constitution prohibiting gas tax revenue from being spent on public transit. Edit 2/23/2023: Three additional states (MI, OK, and CO) have partial restrictions on the majority of gas tax revenue being spent on transit. All of these states are shown in dark blue below. Though constitutional restrictions are much more difficult to overturn, advocates who see their states have these restrictions shouldn’t give up. In some cases, the language may be vague or flexible enough to leave room for transit to receive funding, even if the law hasn’t been interpreted that way in the past. For example, Colorado advocates were able to win transit support by making their fight about the way their gas tax law was interpreted.

States with no restrictions, like California, Virginia, South Carolina, and New York, are shown in light gray. These states allow gas tax revenue to be used for transit, which can serve as a lifeline in times of economic stress.

The bottom line

State spending is a strong indicator of state priorities, and low spending (coupled with a lack of funding options) is a clear sign that transit service is not at the top of state legislators’ minds.

Across the country, the transit fiscal cliff is looming. To weather the storm, agencies require financial assistance, or they’ll be forced to cut valuable service. Now is the time to increase transit spending at the state level. States with statutory and constitutional restrictions on funding for transit will need to think critically about how well these restrictions are serving them and their residents.

Keep an eye out for our next post in this series, which will focus on transit access and driving levels in each state.

6 Comments