The Senate approved their multi-year transportation authorization bill by a 65-34 vote this week. You can view our full statement on the DRIVE Act here from T4America Chairman John Robert Smith. Meanwhile, here are 10 things that you need to know about what’s in the Senate bill.

1) Funding from deficit spending vs. pay-as-you-go

How do you pay for a six-year transportation authorization when the transportation fund is broke and Congress is unwilling to raise the federal gasoline tax? For the DRIVE Act, the Senate bridged the gap between dwindling user fee revenues and total spending by getting creative. In the end, they cobbled together $46 billion in non-transportation-related funds, fees and accounting maneuvers.

Among some of the more controversial “pay-fors” in the Senate bill is a requirement to sell 100 million barrels of the 693 million barrels in the nation’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) between 2018 and 2025, estimated to bring in $9 billion if it can be sold at $95 per barrel ($30-40 more per-barrel than today’s price). Add to that the indexing of customs fees (ironic for a Congress unwilling to index gasoline taxes), an extension of airport TSA fees through 2025, closing estate fee loopholes, and reducing the “fixed dividend rate” the Federal Reserve pays to banks.

But while the bill needs 10 years to recognize some of the new revenues or savings that won’t occur until the 2025, it would instantly transfer billions from the general fund to the transportation fund, increasing the deficit. Senator Bob Corker (R-TN) called it “generational theft,” while T4A Chair John Robert Smith asked, “Is it fiscally responsible to place the cost of paying for three years of transportation investments on the backs of our children and grandchildren?”

A final point of clarification on the length of Senate bill: the DRIVE Act authorizes six years of spending, but provides only three years of funding certainty. In 2018, Congress will have to find an additional $51 billion to fully fund the bill for the remaining three years of its authorization. Despite calls from a diverse cross-section of industry and advocacy groups for a “long-term, sustainable funding solution” for transportation, the DRIVE Act is patched together with temporary and speculative “pay-fors,” the type that are only going to get harder to find three years from now.

| Policy | Ten-year savings |

| Reduce the fixed dividend rate the Federal Reserve pays larger banks | $17.10 billion |

| Sell 101 million barrels of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve | $9.05 billion |

| Index customs fees for inflation | $5.70 billion |

| Extend current budget treatment of TSA fees from 2023 to 2025 | $3.50 billion |

| Use private debt collectors to collect overdue tax payments | $2.48 billion |

| Extend Fannie/Freddie guarantee fees | $1.90 billion |

| Require lenders to report more information on outstanding mortgages | $1.80 billion |

| Close an estate tax loophole about the reporting of property | $1.50 billion |

| Clarify the statute of limitations on reassessing certain tax returns | $1.20 billion |

| Revoke or deny passports for those with seriously delinquent taxes | $0.40 billion |

| Devote civil penalties for motor safety violations to the Highway Trust Fund | $0.35 billion |

| Stop paying interest when companies overpay for mineral leases | $0.32 billion |

| Adjust tax-filing deadlines for businesses | $0.30 billion |

| Allow employers to transfer excess defined-benefit plan assets to retiree medical accounts and group-term life insurance | $0.20 billion |

| TOTAL | $45.80 Billion |

2) Local communities get the short end of the stick…again

The DRIVE Act bypasses America’s cities and towns, reducing the already small amount of funding they directly control to invest in locally-driven projects by nearly $200 million in the first year alone compared to MAP-21. We were extremely disappointed to see a bipartisan amendment from Senators Roger Wicker (R-MS) and Cory Booker (D-NJ), with support from Sens. Casey (D-PA), Durbin (D-IL), Peters (D-MI) and Stabenow (D-MI) fail to receive a fair hearing on the floor. Their plan would have put a larger share of transportation dollars in the hands of local governments by increasing the amount of flexible federal Surface Transportation Program (STP) dollars directly provided to metropolitan areas of all sizes and allowing direct access to the funding for rural areas through a grant program. By failing to bring more dollars, control and accountability closer to the local level, the bill fails to restore the trust of the American people in how our transportation decisions are being made.

3) Progress on a national freight policy but with funding stuck in 20th century silos

The Senate recognized the economic importance of moving goods efficiently throughout the country by including a new freight program that also includes real funding: almost $1 billion in the first year, and up to $2.5 billion annually towards the end of the authorization.

Unfortunately, 90 percent of the dollars reserved for the freight program are restricted to highway projects. This decision runs counter to the realities of how our freight moves: generally, no one product gets to its destination by one mode of transportation, but rather relies on a interconnected and efficient system of ports, rail lines, highways, urban streets and intermodal yards all working together.

There’s a mixed message here. The bill requires USDOT, states and MPOs to conduct thoughtful national- and state-level freight planning to analyze the condition and performance of the freight transportation system and identify the highest priority needs to create greater efficiency and reliability in freight movement, regardless of mode. After all this planning is done, the Senate bill instructs states and MPOs to focus only on highway projects at the expense of rail lines, ports and a truly intermodal network.

4) For the first time, intercity passenger rail is included in a surface transportation bill

While the popular shorthand for the transportation authorization is “the highway bill,” the nation’s transportation program has included dedicated funding for public transportation and bicycling and walking since 1982 and 1991 respectively. But intercity passenger rail has been consistently left out of the overall surface transportation legislation – until now.

For the first time, the nation’s passenger rail policy is included in the bill, laying the groundwork for further improvements and expansion of the nation’s passenger rail service to match the recent unparalleled growth in ridership. Previously, the passenger rail bill has always passed as a standalone authorization, but the DRIVE Act would enshrine the policy in the nation’s surface transportation bill. While the rail programs would still require annual appropriations for funding, it takes an important step forward in providing Amtrak sustainable funding and helping to expand service to meet booming demand.

5) Popular TIGER program fails to win a permanent seat at the table

The USDOT’s competitive TIGER grants represent one of the few ways local communities can directly access federal funds for their local priority projects. While disaster was averted as the bill was being drafted and TIGER hasn’t been changed in this bill, the Senate missed a major opportunity to authorize the program and make it a permanent part of the nation’s transportation policy. If this bill passed, supportive lawmakers will have to continue to fight each year for TIGER funding through the annual appropriations process, resulting in up and down fluctuations in available funding year to year. That makes it tough for local communities to plan and compete within this popular and oversubscribed program.

Nearly one-third of the Senate endorsed Senator Patty Murray’s (D-WA) amendment to authorize TIGER and provide $500 million per year in contract authority via the transportation fund. Unfortunately, along with the Wicker-Booker amendment, this important provision was not given an open and fair hearing on the floor.

6) TIFIA loans can fund TOD, but under a dramatically scaled back program

One of Senator Barbara Boxer’s (D-CA) signature achievements in MAP-21 was an expansion of the TIFIA loan program from nearly $125 million up to $1 billion in annual financing authority. This move greatly expanded an innovative program of low-cost federal financing that doesn’t have to be repaid immediately, allowing the financial benefits of a project to accrue before payments are due. While two good changes were made in the DRIVE Act — making transit-oriented development (TOD) an eligible expenditure and making it easier for local projects, TOD and ITS to access this program by lowering the total project cost threshold lowered from $50 million to $10 million — the program’s funding was scaled back significantly, from $1 billion to $300 million annually.

7) Transit wins additional funds, but projects with private involvement can ‘skip the line’

Overall, public transportation was spared any cuts and in fact received a larger portion of overall authorized funding. As initially introduced by Majority Leader McConnell (R-KY), the DRIVE Act provided transit with 24 percent of the bill’s funding, but the new money used to fill the gap in the transportation fund was directed almost entirely to the highway program. As a result, the mass transit account was set to end the third year of the bill (FY2018) with a negative balance of $180 million. This was fixed on the Senate floor with help from Sen. Durbin (D-IL) and others, and in the end transit received a nearly 25 increase in funding over the six years of the authorization.

One provision in the transit title of the DRIVE Act generating controversy is the ability for projects with any private sector involvement in design, construction, operation, or maintenance of transit projects to jump to the front of the line for the already oversubscribed transit New Starts Program.

8) Active transportation funding survives intact

While the bill represents a missed opportunity for local communities on the whole, the bill slightly increases funding for the popular Transportation Alternatives Program (TAP) to $850 million, but it caps the growth there over the life of the bill. Unlike other programs, this means TAP will not be able to grow with inflation over the life of the six-year authorization.

On a positive note, communities that use TAP to help make biking or walking safer and more convenient will receive 100 percent of the program’s funds, meaning all $850 million will be available to communities. States formerly controlled half of the program’s funds — but no longer.

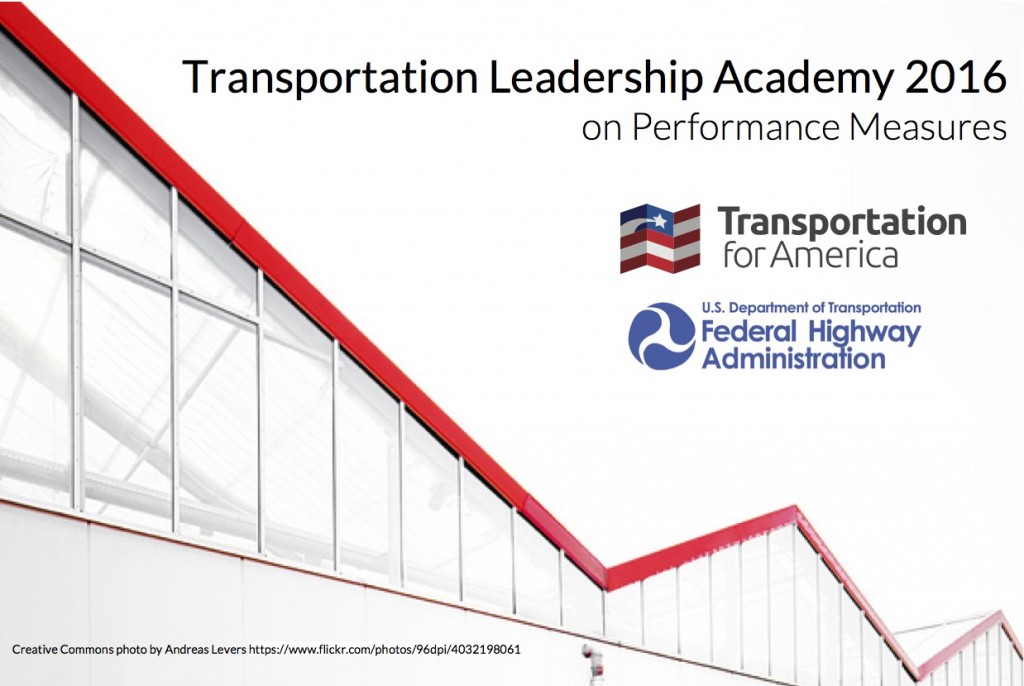

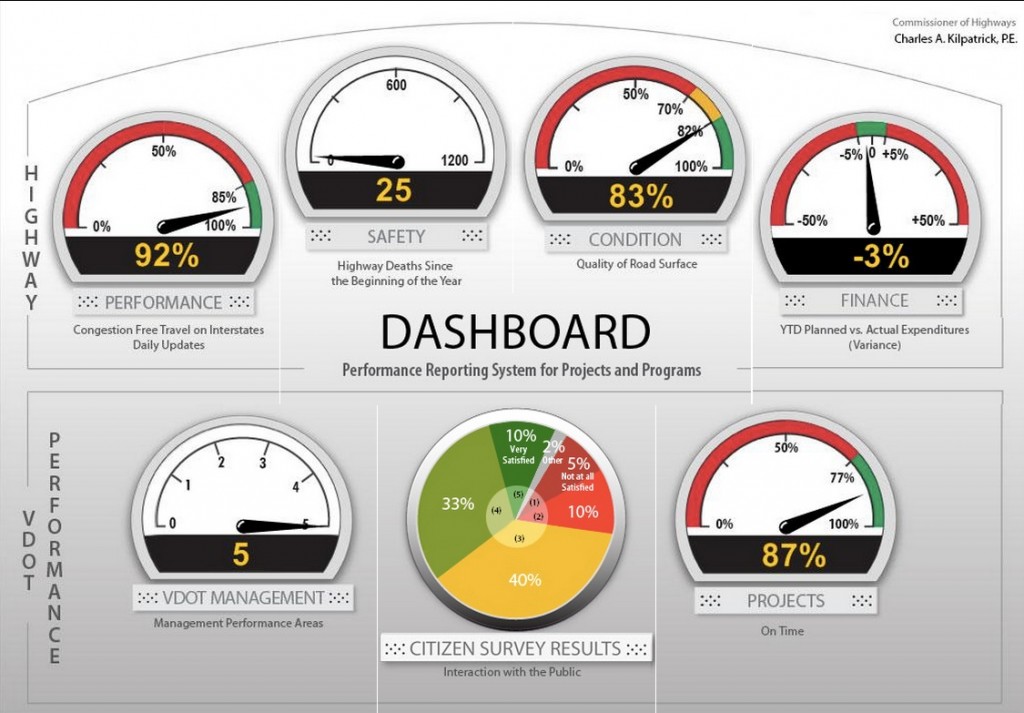

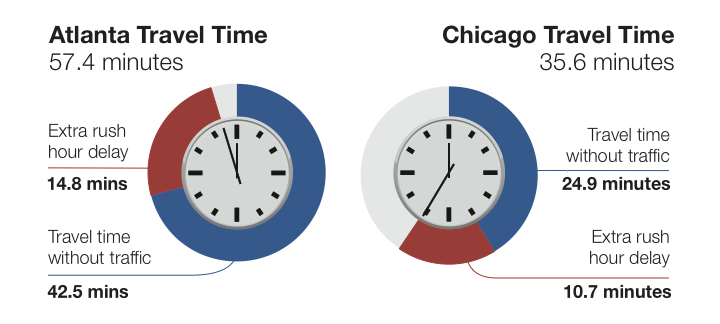

9) Limited progress to improve accountability through performance measures

The DRIVE Act takes one small step to build on project selection and performance management, a key reform of MAP-21. The DRIVE Act provides MPOs and states support in developing their performance measure programs by requiring USDOT to develop datasets and data analysis tools. This includes addressing data gaps for trip origin and destination, trip time and travel mode.

While USDOT has yet to complete their assignment to establish rules for the performance measures contained in MAP-21, there were steps available to the Senate such as including measures such as connectivity and access to jobs or improving project selection processes to open up the “black box” and provide greater transparency and understanding for why one project receives funds over another. None of these positive ideas were included in the DRIVE Act that passed the Senate.

10) Positive advances for next-generation transportation research

At a time when transformative changes in technology are beginning to reshape the transportation landscape, providing an outcome-based 21st century transportation research program is needed now more than ever. Fortunately, this is an area that the DRIVE Act did well. First, the bill establishes competitive funding for local governments and MPOs, among others, to deploy and test innovative research. This is important, since MAP-21 provided limited dollars outside of formula funds to test and deploy the next generation of transportation innovations. Second, the bill would require USDOT to study “shared use mobility” (car-sharing, bike-sharing, ride-sharing, etc.) and other innovative concepts, and provide local and regional leaders best practices and better understanding of the shared use transportation sector. This is important since we need to provide our leaders the understanding of this new transportation sector so that they can adequately plan and provide for its growth.

The last thing you need to know is that the work is far from over. While the Senate passed this long-term bill, both chambers also passed short-term extensions to MAP-21, setting up October 29th as the next deadline to agree on a multi-year transportation bill. Will the House pass the Senate’s bill? Will they draft a bill of their own? Will they fail to do anything and move to another short-term extension in October? Stay tuned.

Louisiana is taking some first steps to fix that process while also trying to raise new money. A recent bill to raise the state sales tax by one cent to fund major projects

Louisiana is taking some first steps to fix that process while also trying to raise new money. A recent bill to raise the state sales tax by one cent to fund major projects