Our director Beth Osborne often jokes that transportation is the first agenda item on politicians’ second to-do list—which is why it never gets done. Most presidential candidates are no different, advocating for business-as-usual transportation funding or embedding transportation across multiple plans. Here’s what’s in them.

Photo of an Amy Klobuchar campaign event in Des Moines by Phil Roeder on Flickr’s Creative Commons.

At Transportation for America, we believe that transportation shouldn’t play second fiddle. Rethinking transportation policy has enormous potential to solve so many of our problems, from economic inequality to climate change. But transportation is consistently glazed over by our political leaders.

Which is why we ranked leading presidential candidates on how well their platforms meet T4America’s three guiding principles for transportation policy: prioritizing maintenance, safety over speed, and access to jobs and services.

But before we begin: If any campaign wants to reboot their transportation platform, give us a ring—we are happy to help!

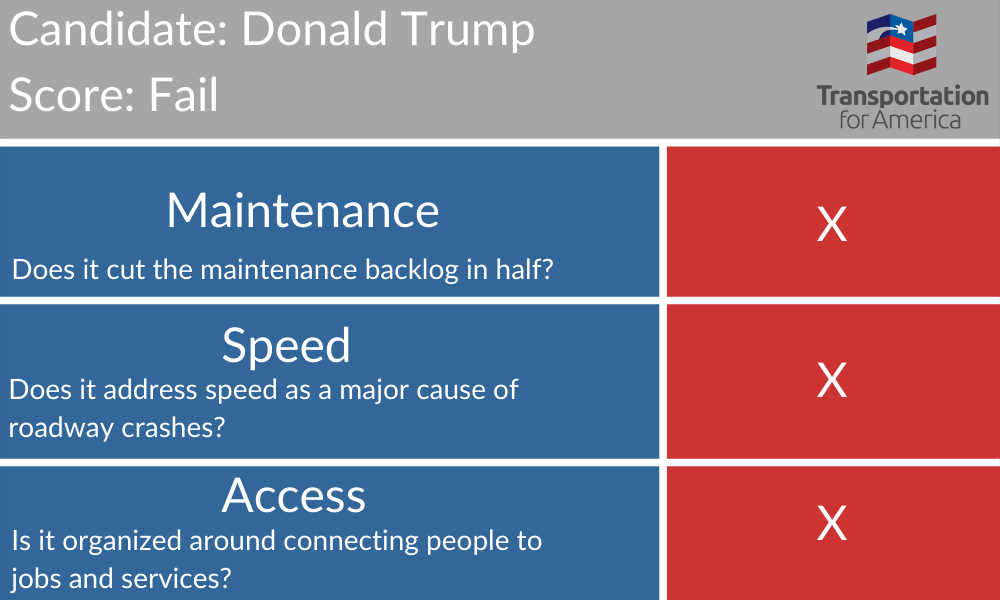

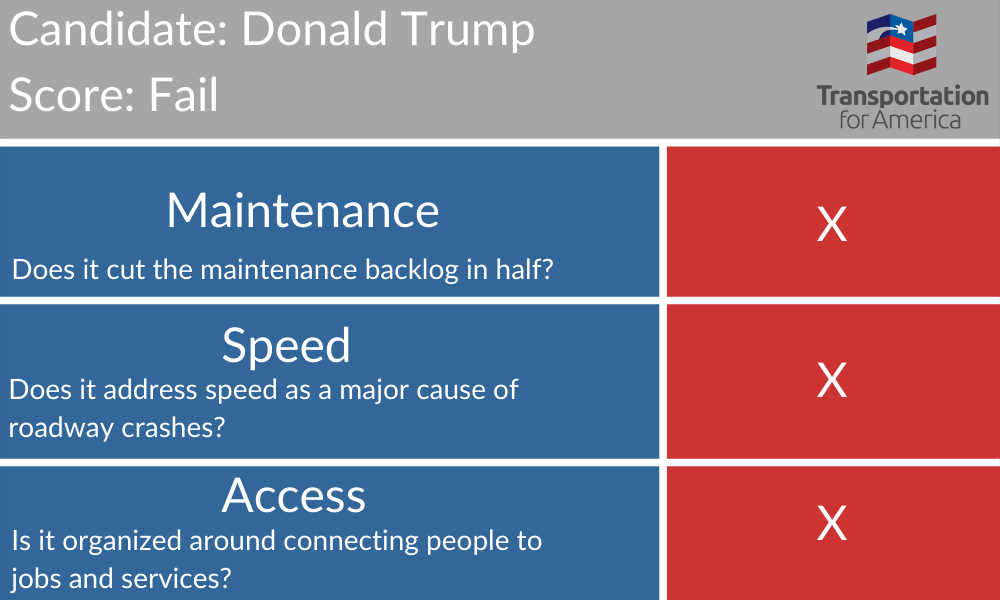

Donald Trump: Fail

Our 45th president is under the false impression that the private sector will “gift” government money to fix our infrastructure. But it will never happen.

Both President Trump’s proposed infrastructure package and the Senate bill that POTUS endorsed during the most recent State of the Union—America’s Transportation Infrastructure Act—fails to achieve our three principles. Billions of new dollars for the existing, broken transportation program with no call to use those funds on repair first, address the unsafe design objectives of the main highway program or measure how well the transportation program connects people to jobs and services. This failure to address the major flaws of the underlying program overshadow the Senate bill’s notable new programs, like a climate title and Complete Streets requirements.

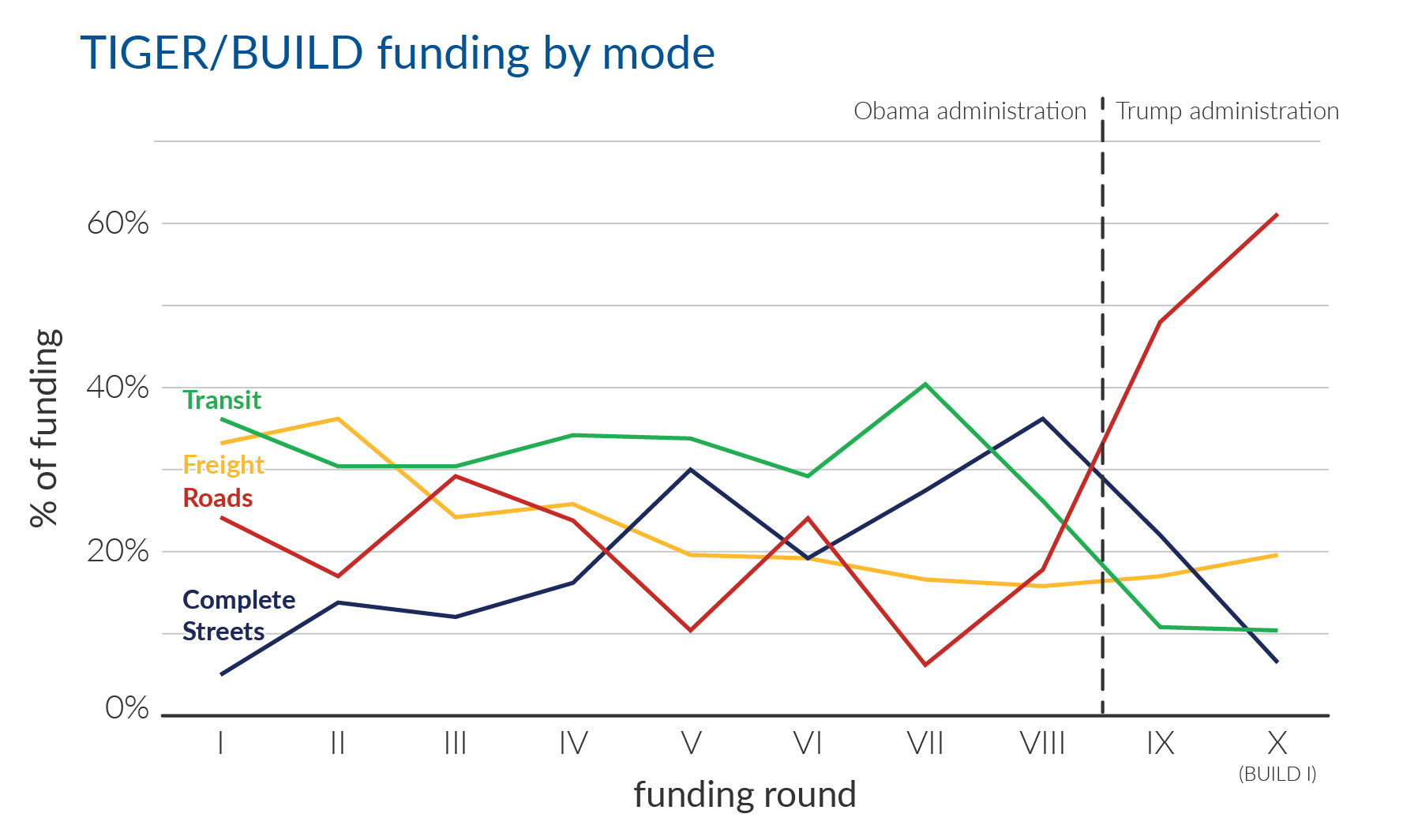

We appreciate that President Trump tried to eliminate the funding silos between modes and infrastructure categories and shake up the transportation program. But his administration’s hostility to transit has slowed the release of transit grants and resulted in a $500 million cut to the critical Capital Investment Grants program—the main source of federal funding to build and expand transit around the country. If President Trump wants to make a difference in transportation, he needs to grapple with the fact that transportation investment will require public dollars.

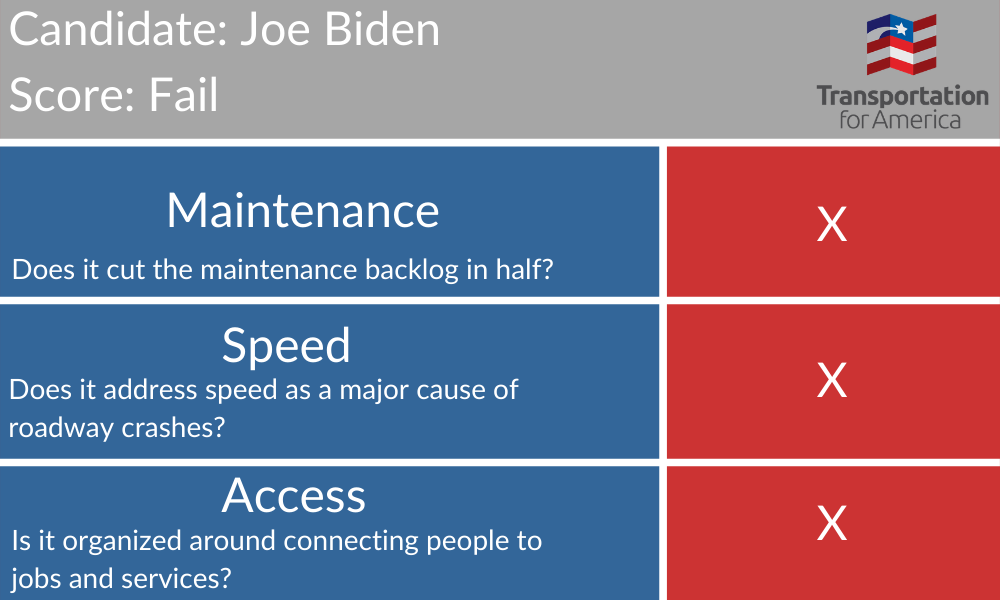

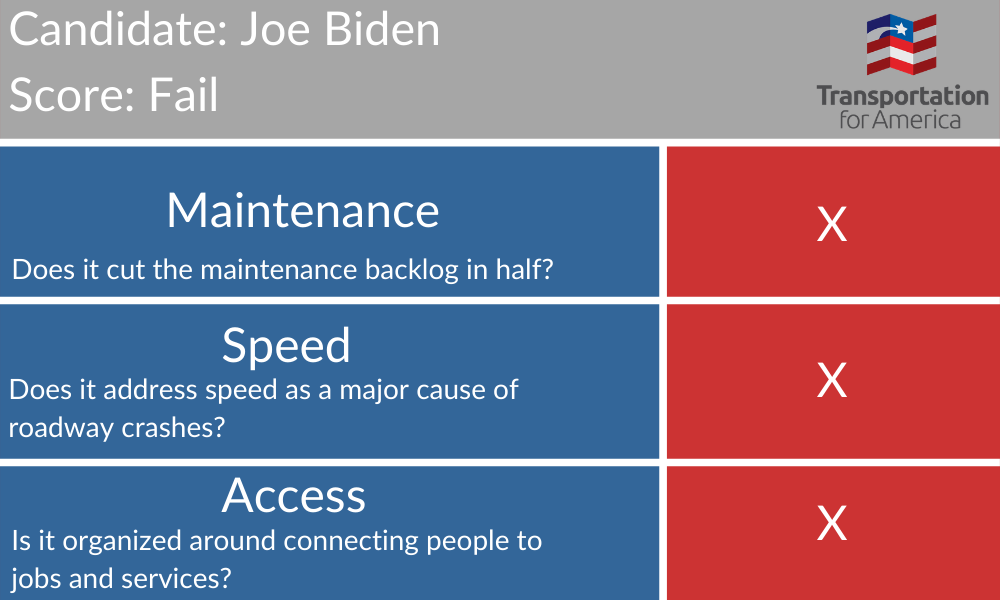

Joe Biden: Fail

Former Vice-President Joe Biden’s plan is business-as-usual. Under his infrastructure plan, federal transportation policy sticks to its storied role as a pass-through program to states and transportation departments, with no real accountability for how the money is spent.

His plan talks about the importance of repairing roads and bridges, but there’s nothing in the proposal to guarantee that it happens. As we learned in our report Repair Priorities, many states spend more on road expansion than maintenance—which is completely legal and would continue to be kosher under the Biden proposal.

To his credit, Biden tries to make up for the emissions and economic damage wrought by the baseline program by funding some side projects—like transit, passenger rail, and Complete Streets. But layering good programs on top of a program that causes the problems isn’t smart policy.

Lastly, Biden’s plan makes no mention of measuring the success of the transportation program by improving people’s access to jobs and services, which is why he flunks on access.

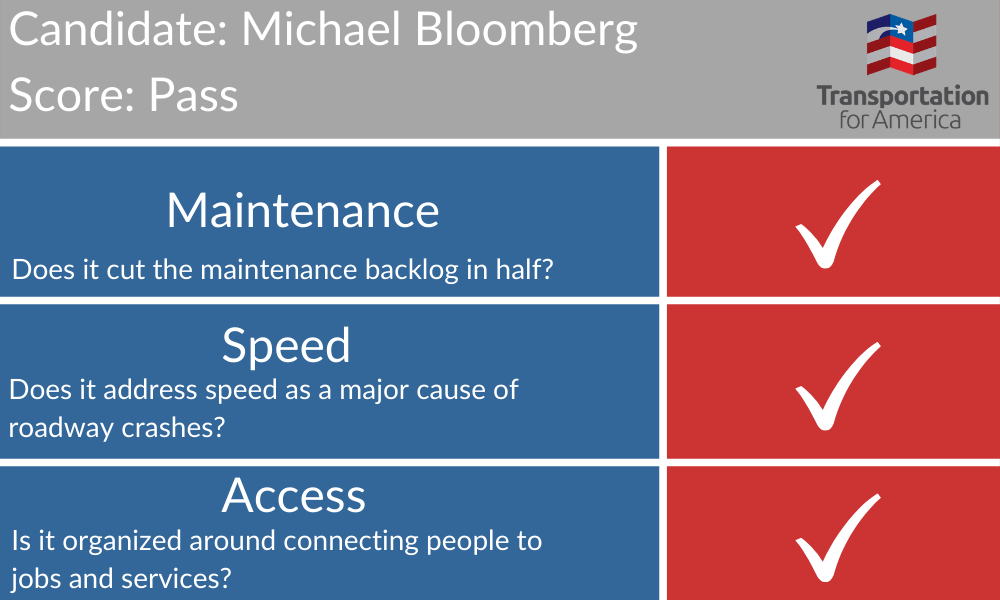

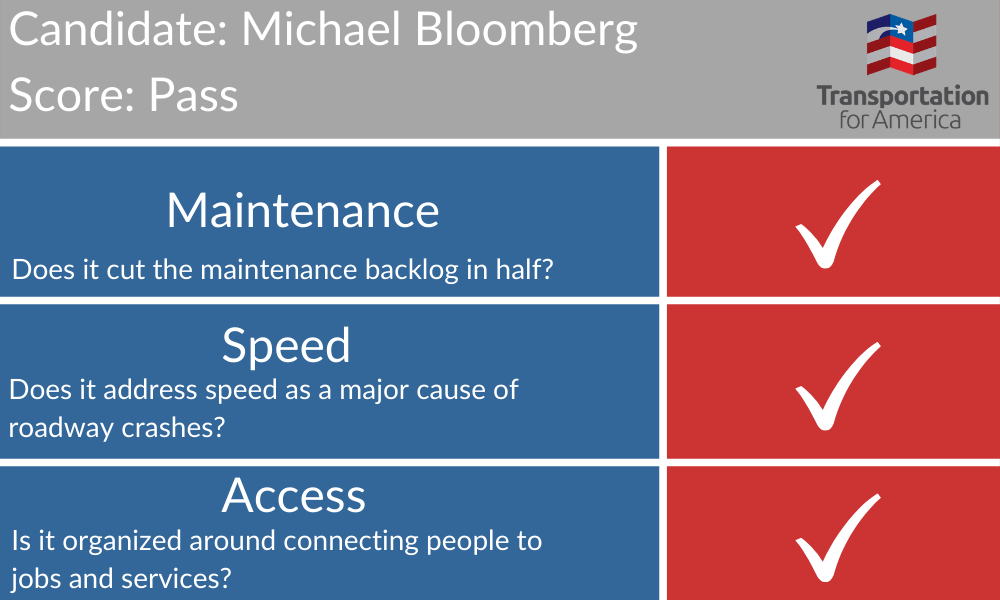

Michael Bloomberg: Pass

There’s a lot to like in Michael Bloomberg’s infrastructure plan. The former New York City mayor is the only candidate who leads with updating and improving the structure of the transportation program itself—not just pouring more money into a broken system. He calls out the transportation program’s total lack of goals and his proposes assessing how transportation projects improve “connectivity to jobs, equity, accessibility, development efficiency, health and environmental effects,” according to his plan.

Additionally, Bloomberg’s plan spends a lot of time detailing the importance of street design in ensuring safety for all road users, which is why he passes our safety metric. He specifically sets a safety goal of saving 20,000 lives by 2025 “by adopting safe street designs, lowering speed limits and implementing other measures.” Setting goals for improved safety at all is a step forward, as there is no federal requirement for states to set safety targets that actually call for fewer fatalities than currently occur in a state.

We’re not thrilled that his first priority is to “fix congestion and bottlenecks.” Oftentimes people interpret this as widening highways; but as many of us know, widening highways only makes traffic worse. However, his proposal calls for addressing congestion by repairing roads and bridges as well as expanding transit.

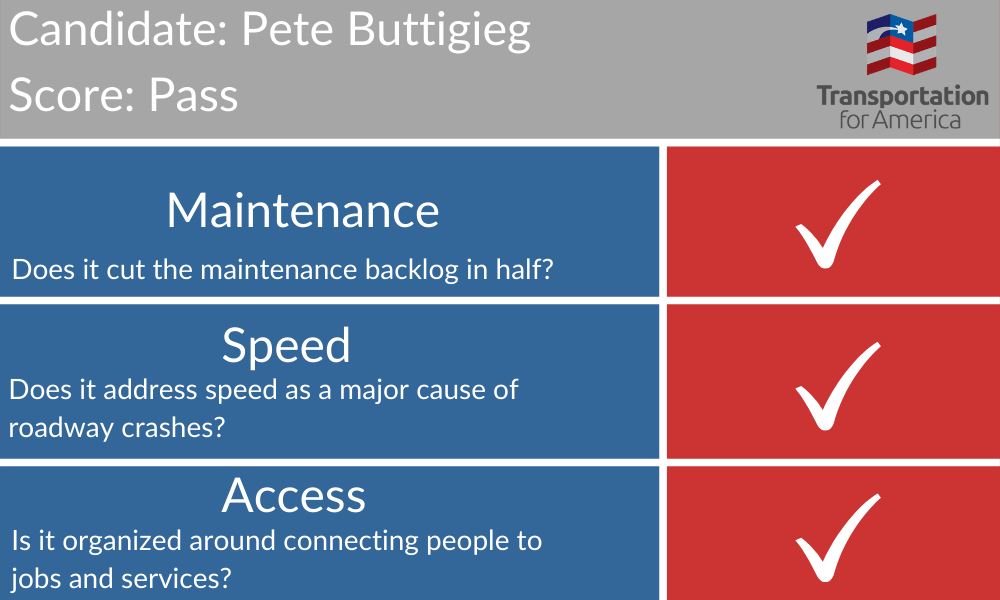

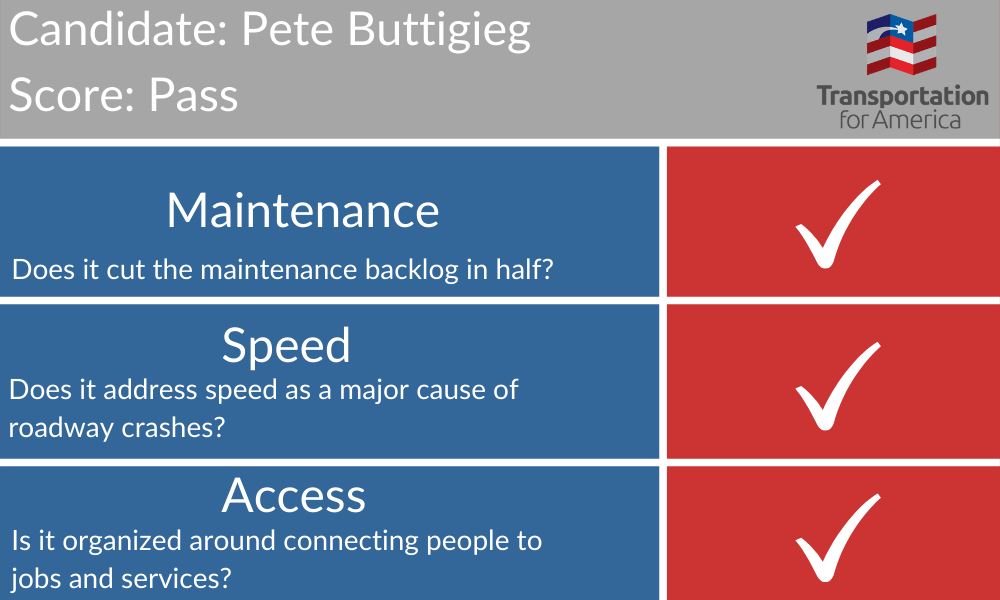

Pete Buttigieg: Pass

Former South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg would make big changes to the formulas at the heart of the transportation program. His plan would require states plan for maintenance before they’re allowed to build new or wider highways with federal funding. Requiring maintenance before expansion earns Buttigieg a ✓ by our standards.

Pete’s plan calls for instituting a national Vision Zero plan, which is radical for a country where states are allowed to set targets for pedestrian fatalities above the actual number of deaths. He would require that states “actively improve their safety records or road design processes, or else lose federal funding for other roadway projects,” according to his plan.

Lastly, Mayor Pete’s plan scores high on access. He would require that states, metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs), and any other recipient of federal transportation funding demonstrate how projects improve access to jobs and services. That is key: requiring progress towards goals—and even setting goals—in order to receive funding is common sense. Sadly, it is not a feature of our current transportation program.

Pete’s plan is similar to Bloomberg’s. The big difference is in how he communicates it: Buttigieg leads with funding, not what he’d do with the transportation program. We think this is a bad way to do policy. After all, in what other policy area (or facet of life, for that matter) do people tell you the price before they tell you what they’re selling?

What isn’t clear is how funding will be shifted between modes, if at all. With a President Pete, are we still in a world where highways get 80 percent of the funding pie, leaving only 20 percent for transit?

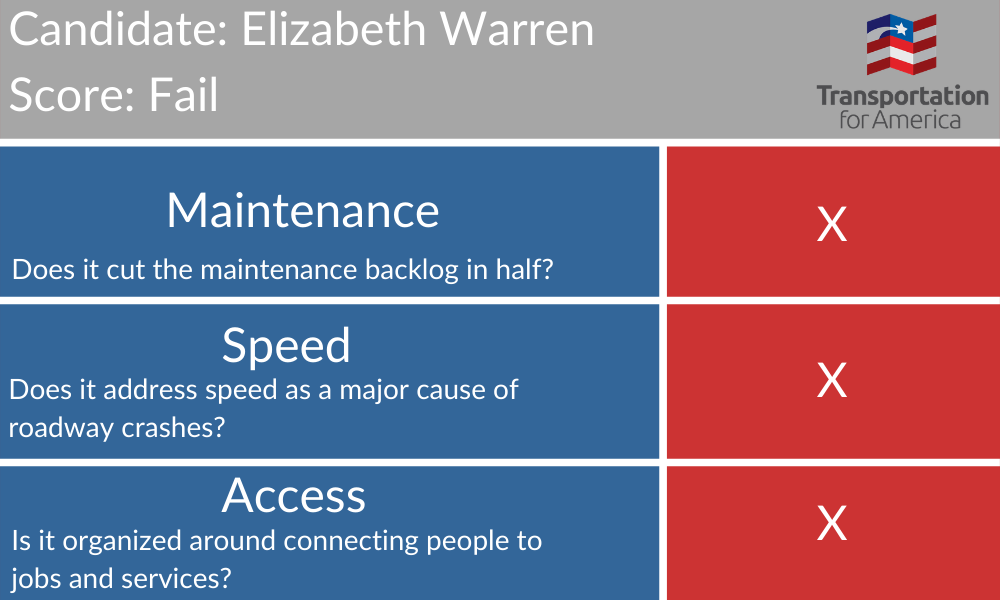

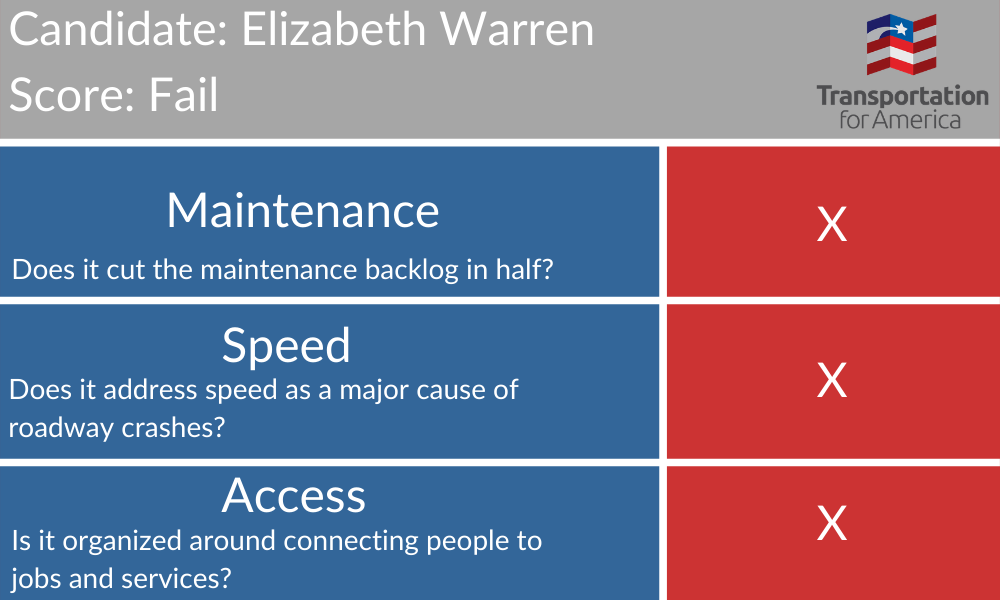

Elizabeth Warren: Fail

Senator Elizabeth Warren’s transportation “platform” leaves a lot to be desired. Her campaign lacks a dedicated transportation plan, embedding the proposal within other policy platforms.

Similar to Biden, Warren proposes new grant programs designed to fix the problems caused by the traditional federal transportation program, but it doesn’t call for fixing the the program itself. She includes additional funding to electrify our vehicle fleet, but there is no mention of creating safe streets for all users and improving access for non-drivers so that people can emit less by using more efficient modes (while having more equitable, affordable access to economic opportunity).

We admire the creative thinking behind Senator Warren’s “Build Green” program, which is modeled off of USDOT’s successful TIGER program (before the Trump administration watered it down and renamed it BUILD). But without changing our current transportation program—one that builds highways we don’t need while our infrastructure crumbles—Warren’s plan wouldn’t bring about the transformation we need.

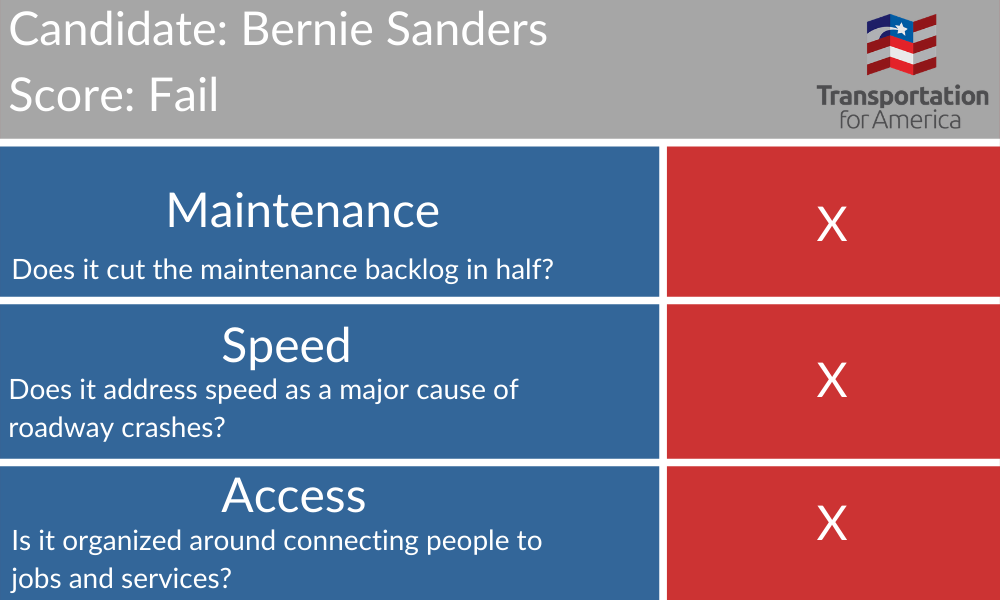

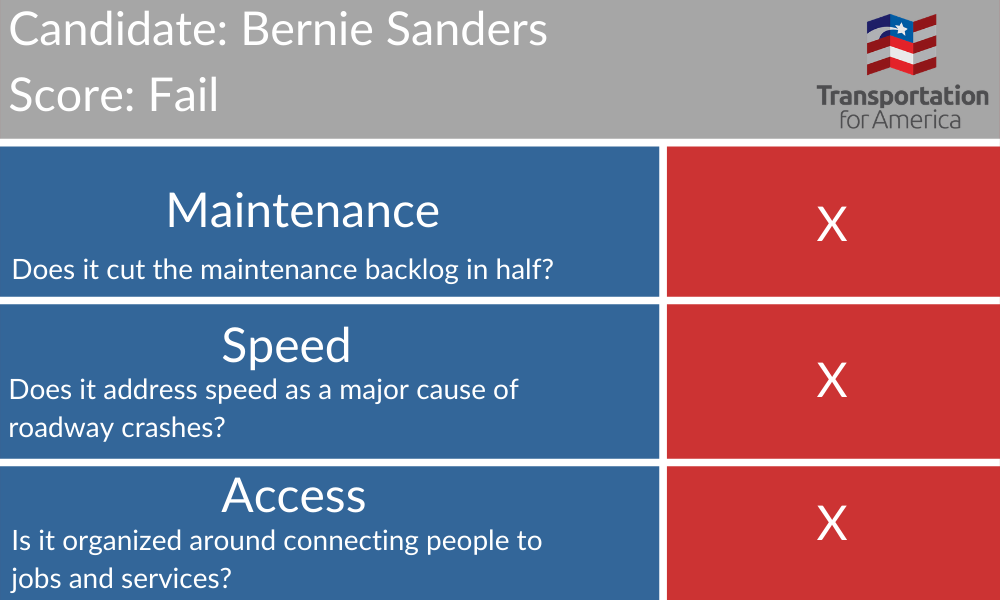

Bernie Sanders: Fail

Senator Sanders’ platform includes so much money.

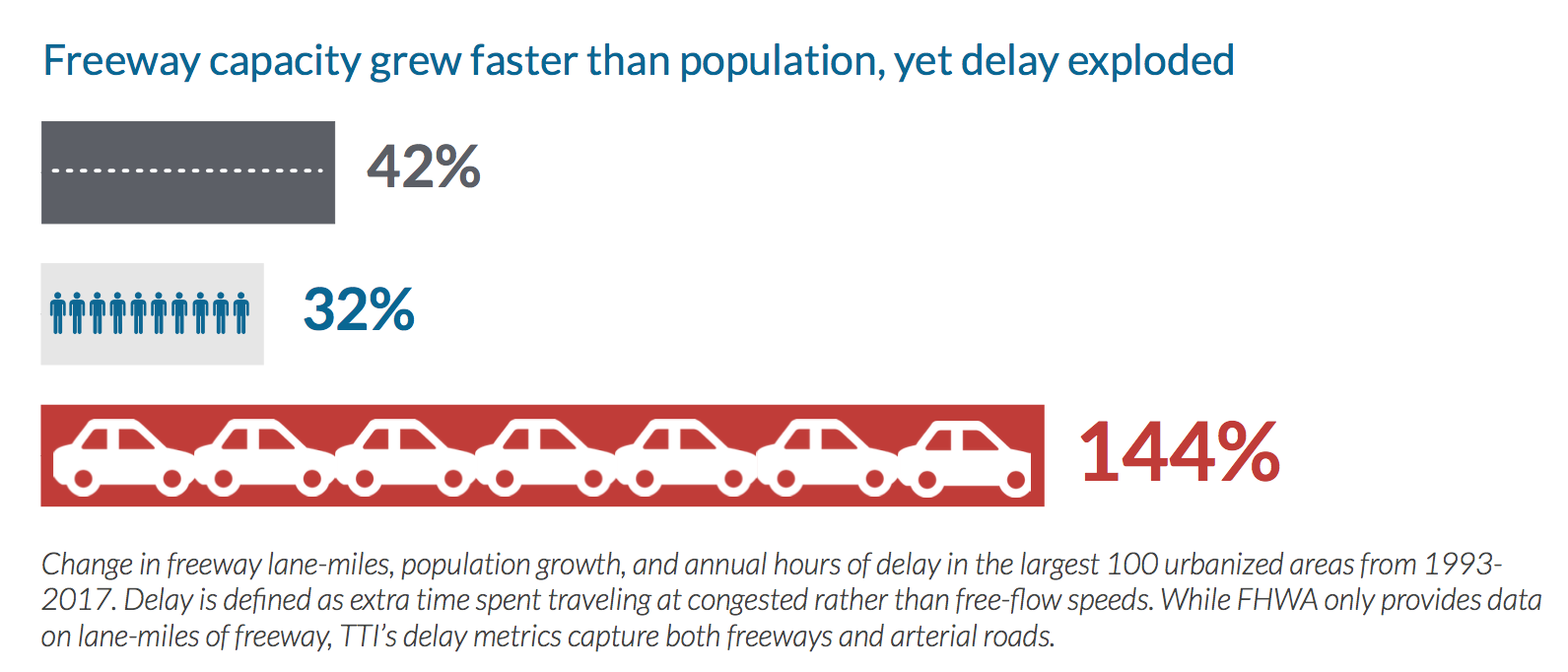

But as we have learned time and time again: more money won’t solve our transportation problems. The problem is what we’re funding, not how much. In fact, more money might make the problem worse.

Sanders’ plan includes $75 billion for the Highway Trust fund “to improve roads, bridges, and other transportation infrastructure,” based off of high 2015 Rebuild America Act. But there are no assurances in the proposal that this money would be dedicated to repair first. We know that when states are not required to repair their infrastructure, they often spend those funds on expansion first. Ribbon cuttings for new things are more fun that maintaining the things we already have, like dessert is more fun than flossing.

While he includes a laudable goal to increase transit ridership by 65 percent by 2030 with a $300 billion investment targeted toward transit-oriented development and improving transit service for seniors, people with disabilities, and and rural communities, there is no mention of investments to make our streets safer so that people can walk to the transit stop. Further, the lack of focus on improving access for all means we would be likely to continue building a program that does not provide equitable, affordable access to economic opportunity.

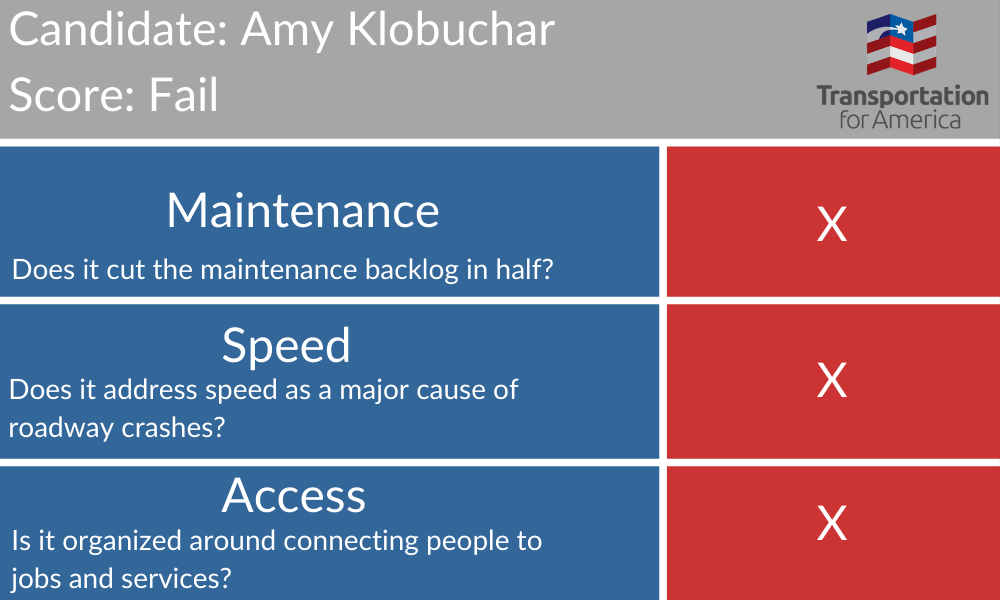

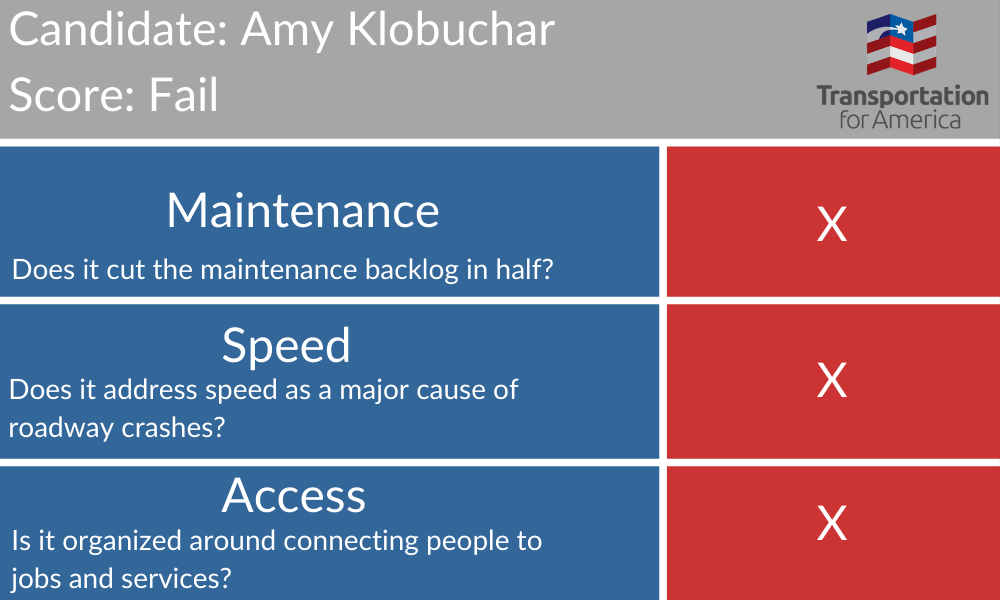

Amy Klobuchar: Fail

Senator Klobuchar’s plan is even more traditional than Joe Biden’s. Her hope is that putting more money into the current program will inspire it to behave in ways it never has before.

Klobuchar—who represents the state where the notorious 35W Mississippi River Bridge collapsed in 2007—pledges to make “smart investments” to repair our infrastructure, but doesn’t guarantee that states will be required to spend federal dollars on maintenance before expansion. This gives Amy an “F” in our book.

Unlike Biden’s plan, however, Klobuchar doesn’t mention Complete Streets—or any safety measures, for that matter. In addition, Amy doesn’t mention measuring the success of transportation programs by how well they connect people to jobs and services. In fact, performance standards don’t come up once in her plan.

In conclusion…

Only two of the presidential candidates—both former mayors—receive passing grades on their transportation plans, according to our three principles. Only two of the many politicians vying to be the most impactful person in the country understand what it takes to save Americans time, money, and from the dangerous effects of unchecked climate change.

Further, not one candidate speaks honestly about how to pay for their proposed funding increases. In fact, they all seem to propose that we abandon the user pays system, which in many ways we already have. If so, bye-bye, trust fund. They all seem to propose we fund this by deficit spending (as we have been for the last decade) or maybe taxing the wealthy or getting magical private funds?

This reminds us of something former Sen. Bob Corker of Tennessee once said about transportation funding: “If something is important enough to have, it’s important enough to pay for.” We’d like to add: If you aren’t willing to pay for it then you don’t believe it is important enough to have.

More money isn’t the solution to our transportation problems. It’s rethinking what we fund. But lawmakers often rely on the rules set by the outdated Highway Trust Fund to make this critical decision for them.

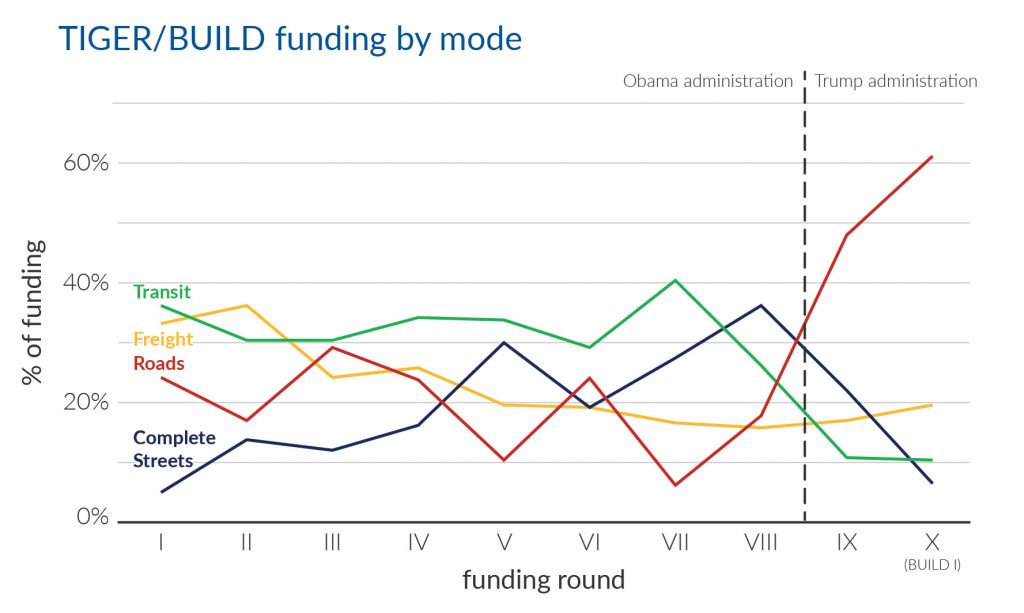

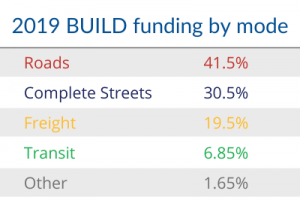

But there is a bit of a silver lining: Complete Streets & other multimodal projects racked up almost a third of the BUILD funding, the highest percentage such projects have received under the Trump administration. This is also particularly notable given the worrying rise in pedestrian and bicycle fatalities across the country, attributable in large part to the lack of safe infrastructure on our roadways for people without cars.

But there is a bit of a silver lining: Complete Streets & other multimodal projects racked up almost a third of the BUILD funding, the highest percentage such projects have received under the Trump administration. This is also particularly notable given the worrying rise in pedestrian and bicycle fatalities across the country, attributable in large part to the lack of safe infrastructure on our roadways for people without cars.