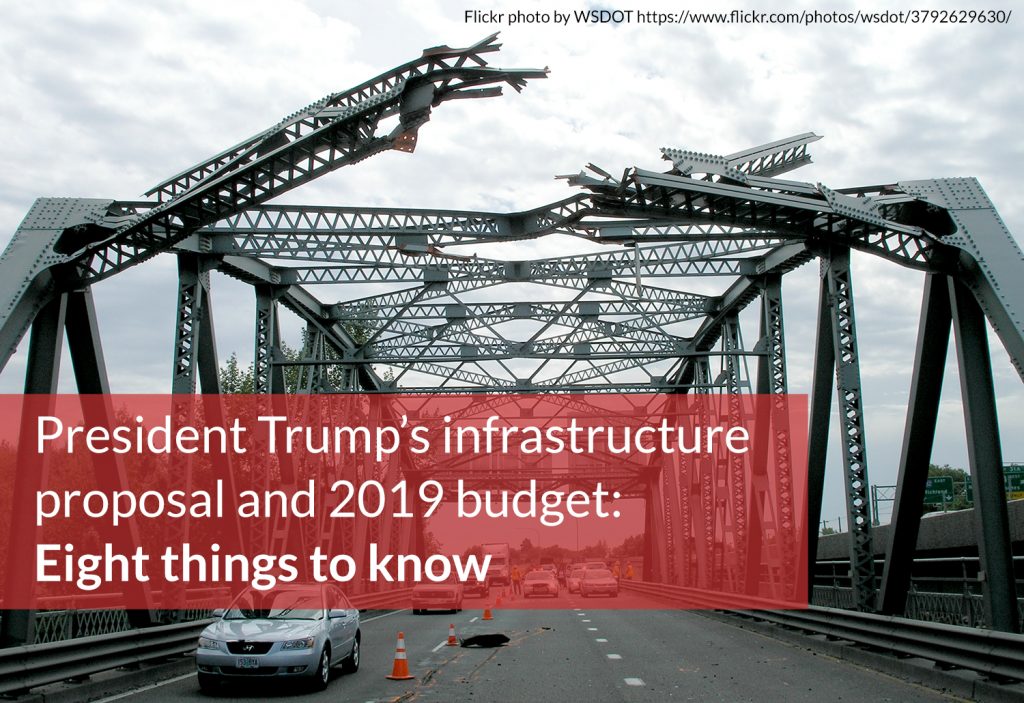

After promising the release of an infrastructure plan since the early days of his administration over a year ago, President Trump finally released his long-awaited plan for infrastructure investment. Since he did it on the same day he released his budget request for the next fiscal year, it’s worth considering them together and asking: what do these proposals mean for infrastructure?

Here are eight things worth knowing about both the president’s infrastructure plan and his budget for 2019. Read T4America’s full statement on both proposals here.

1) “One cannot claim to be investing in infrastructure on the one hand while cutting it with the other.”

By only including a modest $200 billion in federal investment over ten years, the president’s so-called $1.5 trillion infrastructure plan isn’t a real plan—it’s a hopeful call for local communities, states, and the private sector to invest $1.3 trillion of their own money in infrastructure while the federal government largely sits on the sidelines. Look even deeper and you’ll discover that the $200 billion in federal investment isn’t actually new money overall—it’s mostly sourced from cuts to other programs, including key transportation programs. The president calls for large investments in infrastructure on the one hand while proposing to cut infrastructure programs in the budget with the other hand. Considered together, the infrastructure plan is like getting a bonus from the boss after their new budget just slashed your salary.

2) If the goal is to repair “crumbling” infrastructure, why not require it?

If our infrastructure is “crumbling,” why advance an infrastructure plan that doesn’t do anything to require that states or cities prioritize repair and maintenance with the new funding? Why give out new money that states can spend on costly new infrastructure with decades of built-in maintenance costs when we can’t afford to maintain what we’ve already built? A proposal meant to address America’s crumbling infrastructure almost never mentions maintenance or repair anywhere within it.

“One of the reasons there’s a break in trust between the taxpayer and the federal government is that there’s only so many times you can come before the taxpayer and say, ‘our nation’s roads and bridges are crumbling, please give us more money to fix it,’ and then not dedicate it to fixing it,” noted T4A senior policy advisor Beth Osborne on CBC News on Monday evening. We’ve made this point routinely over the years: Why do we keep spending hefty sums on new roads and new lanes while repair backlogs get ignored?

Little accountability, no performance measures: In addition, though this proposal claims to be outcomes-based, there is almost no mention of actual goals. It proposes to invest new money, but to accomplish what exactly? It includes no requirements to measure how these billions will lead to improved roads, bridges or transit systems, better connect people to jobs and opportunity, or move people and goods more efficiently. There are no requirements to measure performance or hold anyone accountable for accomplishing specific goals with the money.

3) Ends federal support for building or improving public transportation

Just like the president’s first budget proposal released a year ago, this one also calls for an immediate halt to federally supported transit projects by eliminating 100 percent of funding for transit projects in development that don’t already have signed funding agreements with the federal government. This pulls the rug out from under at least 41 cities—many of whom have already raised new transportation revenues from voters at the ballot box—that were fully expecting the federal government to share around 50 percent of the cost. While transit projects could still theoretically compete for funding from the plan’s “incentives” program, they would have to compete against transportation, water, waste, power, and broadband projects for a smaller pool of funding.

Seattle is one of many cities that have raised new transportation revenues for transit at the ballot box with the full expectation of a federal contribution to help complete their projects.

4) Roadway projects will be free of new requirements to create value that would be imposed on transit projects

Value capture is a creative way to finance transit projects by “capturing” some of the increased land value that transit provides and using those anticipated revenues on the front end to pay a share of the costs. It can help fund transit improvements, but it’s not a solution that works everywhere, in part because many states don’t allow it and/or most transit agencies have zero control over land use. This infrastructure proposal treats transit projects differently than all other modes by requiring the use of this financing mechanism. New roads? They won’t even need to create a dime of new value to win funding from new incentive or grant programs, much less capture any of that value to pay for their costs. Like Alabama’s $5.3 billion, 52-mile bypass, known as the Northern Beltline, to be constructed north of Birmingham. At $102 million per mile, the project will be one of the country’s most expensive roadway projects, yet it and projects like it would be exempt from these requirements to create any value to pay a share of the costs.

This top-down requirement would put a burden on new transit projects that is not placed on any other new transportation investment and would essentially halt the development of dozens of smart transit projects across the country. It would also jeopardize funding for capital improvements for more than 400 rural transit providers where value capture is rarely feasible.

5) Cities and states already raising new transportation funding will have to do even more

The federal government hasn’t raised the gas tax since 1993. Since just 2012, 31 states have raised new transportation revenues — mostly by raising or otherwise modifying their fuel taxes. Yet the largest program ($100 billion) in this proposal flips the script and puts the onus on these same local and state taxpayers by changing the federal match on new projects from 80 percent to 20 percent. Asking localities to simply kick in more money would do little to guarantee better projects or even less reliance on federal funding—it’ll just occupy more of the local funding that states or cities could invest elsewhere or spend on long-term maintenance, and could just incentivize huge tolling projects, others with some sort of repayment mechanism, or the sale of public assets.

It either devalues or ignores outright local dollars already raised: This proposal penalizes cities like Indianapolis, Seattle, Raleigh, Albuquerque, Los Angeles, Atlanta and scores of others that have already done the hard work of securing new local funding for transportation. How? Though localities are required to come up with 80 percent of a project’s cost, the plan ignores any funds raised more than three years ago—even if it’s a tax producing new revenue today. And for new funds raised within the last three years, there’s a sliding scale for how much those dollars are worth. The specific percentages aren’t detailed in the plan, but for example, $1.00 raised at the ballot box two years ago might only be worth 0.50¢ toward the 80 percent local share required by this plan. Many of those cities (and the 31 states) would have to raise yet more new funding to qualify.

6) It eliminates TIGER, one of the few competitive programs that exist today

The proposal completely eliminates the fiercely competitive TIGER program. This $500 million grant program is one of the few ways that local communities of almost any size can directly receive federal dollars for their priority transportation projects and one of the most fiscally responsible transportation programs. TIGER projects brought 3.5 other dollars to the table for each federal dollar awarded through the first five rounds. And the competition for funds is in stark contrast to the majority of all federal transportation dollars that are awarded via formulas to ensure that all states or metro areas get a share, regardless of how they’re going to spend those dollars. Unlike the old system of congressional earmarks, the projects vying for funding compete against each other on their merits to ensure that each dollar is spent in the most effective way possible. There’s a reason that TIGER remains so popular with local communities even though around 95 percent of applicants lose in every round—it’s one of the only ways to fund the multimodal projects that are difficult to advance through conventional, narrowly-focused federal programs.

7) Money is set aside for rural areas, but governors will still control it

The plan sets aside $50 billion for rural areas, allocated directly to governors and awarded at their discretion to the projects that they choose. Each governor’s share will be determined via a formula that considers only lane miles and population while purporting to build transportation, water, waste, power, and broadband infrastructure. Is lane-miles an adequate metric for the full range of needs that our rural areas have? Block-granting money to states does not guarantee that local communities will get funding to invest in their highest priority infrastructure projects. Incentivizing cities and towns through competition is proven to be more effective in producing long-term results.

Without this money set aside, rural areas (and smaller cities) would have few chances to successfully win funding from the plan’s $100 billion incentives program. As Aarian Marshall wrote in Wired today, it “would favor applicants that can ‘secure and commit’ continuing funds for their project, including future money for operation, maintenance, and rehab. The ventures, in other words, that can pick up most of the tab. That’s a problem for cities that don’t have steady funding streams, or that find themselves in any of the 42 states that restrict locales’ rights to tax their citizens.” And these smaller areas will never be attractive places for the private investment that this plan assumes will materialize to make up that $1.3 trillion funding gap.

8) Makes long-term cuts to overall transportation funding

Buried in the document is a tiny yet significant detail about scaling down overall transportation spending by as much as $21 billion each year by the end of the decade due to the declining value of the gas tax. So in addition to making cuts to core transportation programs and providing no new revenue for transportation in the infrastructure proposal, the budget actually proposes to reduce transportation investment overall year by year, putting the screws to the cities, towns, and transit properties that depend upon formula funding to operate and maintain existing transportation programs or to make critical capital improvements.

Considered with the president’s FY19 budget request, this infrastructure plan will result in a net reduction in transportation spending and investment. It does not require that we first repair the myriad of assets already in a state of disrepair. It punishes communities that have already stepped up to address their own infrastructure challenges. It leaves rural areas without any guarantees and it hollows out the core funding for transportation that has carried the program for more than a generation. We strongly urge Congress to start over and craft a plan that provides real funding, fixes our current infrastructure inventory, funds smart, locally-driven and supported projects, and requires performance measures that enable taxpayers to understand what benefits they will receive for their investments.