Seven things to know about President Trump’s budget proposal

There is no good news for transportation in President Trump’s first budget request to Congress. We take a look beyond the headlines and unpack seven things you need to know about this first salvo in the annual budget-making process.

Members-only content

If you are an active T4America member, please log in to read the exclusive content hidden here. There are numerous benefits to membership — join today.

The short version is that President Trump’s first budget request for Congress is a direct assault on smart infrastructure investment that will do damage to cities and towns of all sizes. After months of promises to invest a trillion dollars in infrastructure, the first official action taken by the Trump administration on the issue is a proposal to eliminate the popular TIGER competitive grant program, cut the funding that helps cities of all sizes build new transit lines, and terminate funding for the long-distance passenger rail lines that rural areas depend on.

Tell your representatives that this proposal is a non-starter and appropriators in Congress should start from scratch.

That’s the short version. Here’s a longer one with seven things worth knowing more about:

1) It ends the program for building new transit lines or service, putting the screws to local communities that have raised their own dollars to build vital projects.

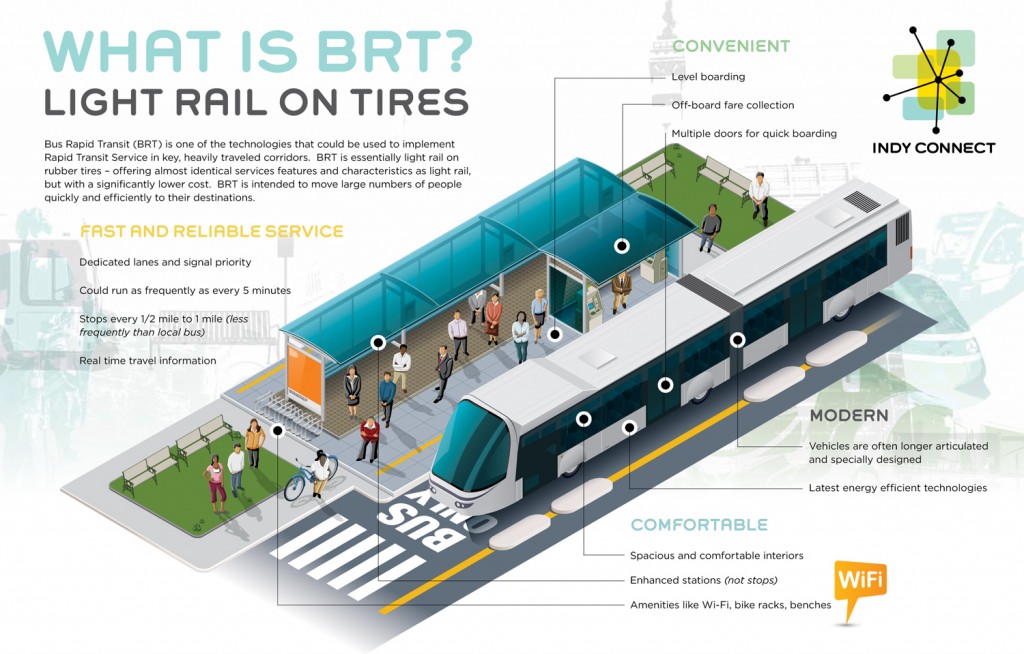

Indianapolis would be facing the loss of more than $70 million in anticipated federal grants for their Red Line bus rapid transit project under this budget. Graphic courtesy of Indy Connect

This budget eliminates future funding for building new public transportation lines and service, threatening the ability of local communities of all sizes to satisfy the booming demand for well-connected locations served by transit. While the handful of projects with full federal funding grant agreements (FFGAs) already in hand would (theoretically) be allowed to proceed, all other future transit projects would be out of luck. The budget proposes to phase out future funding for what’s called the transit capital investment grants program — more informally referred to as New Starts, Small Starts and Core Capacity grants. As we said in our statement, it’s a “slap in face to the millions of local residents who have raised their own taxes, with the full expectation that [their funds] would be combined with the limited pool of federal grants, to complete their priority transportation projects.”

For example, here’s a list of eight transit projects we quickly identified that have already raised or set aside a share of the local dollars required and were recommended by the Federal Transit Administration for funding in 2017 — though they were just short of the last step of receiving a federal grant agreement.

- Sacramento, CA — Streetcar extension

Expecting $74.9 million Small Starts grant to match $65 million in various city and county funding. - Kansas City, MO — Bus rapid transit

Expecting $30 million Small Starts grant to match to match $12 million in city and $3 million in regional sales tax funds. - Tempe, AZ — Streetcar

Expecting $74.9 million Small Starts grant in FY17 which would match $76 million in local sales tax funds approved by Maricopa voters in 2004. (Local voters have been paying local sales tax for 13 years in expectation of federal funding to build this project.) - Ft. Lauderdale, FL — Streetcar extension

Expecting $61 million Small Starts grant in FY17. Would match $48 million in combined city and county financing, including local gas tax, special district property assessment, and county general funds. - Indianapolis, IN — Red Line bus rapid transit project

Expecting $74.9 million Small Starts grant to pair with the income tax increase that voters just approved in November 2016 at the ballot box - Minneapolis, MN — SW Light Rail Line

Expecting $887 million New Starts grant in FY17 to cover 50 percent of the project. The other 50 percent would be covered locally. Local and regional entities (Counties Transit Improvement Board and Met Council) already stepped up in September 2016 and increased their commitment after the state backed out of their funding commitment to the project. - Albuquerque, NM — Bus rapid transit

Expecting $69 million Small Starts grant to match $25 million in various local (city and county) funds - Lynwood, WA — Sound Transit light rail extension

Expecting $1.172 billion New Starts grant, matched by the same amount of voter-approved, local sales and motor vehicle taxes. Local funds were approved by the Sound Transit 2 referendum in Nov 2008; voters just expressed their continued commitment by approving additional transit funding in the successful Sound Transit 3 referendum in Nov 2016.

Aside from these eight, there are at least 40 other transit projects in other various stages of development — engineering, planning, etc. — that will be left completely on their own with no future federal dollars for transit construction. (Yonah Freemark has a good list of them in this post from The Transport Politic.)

Practically speaking, it’s unclear how the administration would even go about phasing out the program. It would require several years of keeping spending level just to honor the federal government’s current obligations. Right now, there’s about $6 billion committed to the projects that have federal grant agreements. With over $2 billion budgeted annually for this program over the last few years, it would take almost three years of continuing current funding for the program just to clear those projects and end the program.

2) It eliminates the TIGER program, and then recommends unsuitable alternatives to fund those sorts of local projects

The proposal completely eliminates the fiercely competitive TIGER program, which is one of the few ways that local communities of almost any size can directly receive federal dollars for their priority transportation projects and one of the most fiscally responsible transportation programs administered by USDOT.

View our interactive map of winners through all rounds of TIGER

The federal government has found a smart way to use a small amount of money to incentivize the best projects possible through TIGER, as well as encourage local investment —TIGER projects brought 3.5 other dollars to the table for each federal dollar awarded through the first five rounds. And the competition for funds is in stark contrast to the majority of all federal transportation dollars that are awarded via formulas to ensure that all states or metro areas get a share, regardless of how they’re going to spend those dollars. Unlike the old system of congressional earmarks, the projects vying for funding compete against each other on their merits to ensure that each dollar is spent in the most effective way possible.

In response to the elimination of the TIGER program, the administration blithely suggested in their proposal that local communities instead turn to other programs…that are explicitly designed not to meet same needs as TIGER. “DOT’s Nationally Significant Freight and Highway Projects grant program, authorized by the FAST Act of 2015, supports larger highway and multimodal freight projects with demonstrable national or regional benefits. This grant program is authorized at an annual average of $900 million through 2020.”

Well, sure, but only $100 million of that $900 million in any year can be used on projects that aren’t on the national freight highway network, so if your project is multimodal or otherwise not on a key national highway, you’re probably out of luck. And the FASTLANE competitive grant program is wholly limited to freight projects.

There’s a reason that TIGER remains so popular with local communities even though around 95 percent of applicants lose out on funding — it’s one of the only ways to fund the multimodal projects that are difficult to fund through conventional, narrowly-focused federal programs. The replacements suggested by the administration aren’t appropriate and don’t come close to funding the same sort of projects or meeting the needs as TIGER.

3) It terminates the funding for long-distance passenger rail that keeps rural communities connected.

While preserving funds for the northeast rail corridor, it ‘terminates’ funding for long-distance passenger rail service. One of the things we were nervous about in the FAST Act was the way it started to separate out the northeast passenger rail corridor from the rest of the system. Bifurcating the funding for our rail network starts to chip away at the idea of a national system and will hit rural communities especially hard.

It’s jarring to read in the administration proposal that the intent of reducing Amtrak funding is to “focus resources on the parts of the passenger rail system that provide meaningful transportation options within regions,” especially when you consider that “providing meaningful transportation options” is precisely what the Gulf Coast communities trying to restore passenger rail service wiped out by Hurricane Katrina are trying to do.

Combined with the proposal to end the Essential Air Service program, rural communities could be more disconnected than ever before.

During last year’s Gulf Coast Inspection Train, hundreds of Gulfport, MS residents came out to voice their support for bringing passenger rail service back to the coast to provide them with “meaningful transportation options.”

4) This budget indicates that the much-discussed infrastructure package — if it ever even materializes — would be hostile to the approach taken by the above programs.

Are you one of the people who are still optimistic that a big infrastructure package from the President would provide robust funding for the types of projects that were just slashed in the budget? Let Mick Mulvaney, director of the Office of Management and Budget, disabuse you of that notion. When asked about the transportation programs that were cut or eliminated, Mulvaney said, “we believe those programs to be less effective than the package we’re currently working on.”

I.e., they don’t think that the approach taken by TIGER, New Starts, etc. is an effective one, and they’re going to go in a different direction in any big infrastructure package, and these cuts reflect the transportation priorities of the administration.

5) It suggests a performance-based approach while delaying the rules on new performance measures

This is a smaller point, but the administration’s rhetoric on better-performing federal agencies doesn’t sync up with their actions thus far. From the proposal:

The Administration will take an evidence-based approach to improving programs and services—using real, hard data to identify poorly performing organizations and programs. We will hold program managers accountable for improving performance and delivering high-quality and timely services to the American people and businesses.

Meanwhile, new performance measures (like the new congestion rule) that could actually improve the effectiveness of federal transportation spending were put on hold as the new administration took office, to say nothing of the fact that competitive programs like TIGER are far more performance-driven than the simple formula grants that are handed out like blank checks to states regardless of how they’ve spent that money in the past.

6) It cuts scores of other programs that help support strong local economies.

As our parent org Smart Growth America said last week, the transportation-related cuts are just one aspect of a budget that is “a broadside against the things that make communities work.” It takes the axe to HUD’s Community Development Block Grants (CDBG), stormwater grant programs, USDA’s Rural Development Program, and scores of other programs that support redevelopment and strong local economies.

More from SGA:

States and local communities are ill-prepared to take over functions and costs that have heretofore been borne by the federal government. American infrastructure needs maintenance and reinvestment not disinvestment. Economic development will not be enhanced by cutting off the tools that local governments and the private sector use to revitalize and redevelop downtowns and neighborhoods. Asking local governments to fill these gaps will force communities to choose between good transportation and attainable housing, or between support for small businesses and support for low-income families and that is a losing proposition from square one.

Communities cannot be built piecemeal, and this issue can’t be solved with small changes to line items. Americans shouldn’t have to choose between good transportation and attainable housing, or between support for small businesses and support for low-income families. These programs need to work together in order to succeed.

7) It’s important, but this is only the starting point for the budget process

Presidents make their request, but appropriators in Congress determine the budget and House appropriators will soon go to work on producing their own. From a Capitol Hill transportation reporter:

General Congressional GOP reaction to Trump’s budget: Thanks big guy but we’ll take it from here. Congress makes the budget.

— Tanya Snyder (@TSnyderDC) March 16, 2017

That said, appropriators in the House or Senate could propose some of the same cuts. After all, it was Congress in 2012 that tried to eliminate all federal mass transit funding, so it’s crucial to let them know what your priorities are.

Our nation’s infrastructure serves as the backbone for economic growth and prosperity, and we need a budget that prioritizes investment in the local communities that are the basic building block of the national economy.

Stand up and send that message loud and clear to Congress.

TAKE ACTION

Pingback: Trump Moves to Immediately Gut Transit Expansion and TIGER Funding – Streetsblog USA