With the Biden presidency in the rearview mirror, we can look back at where the administration succeeded and failed and what lessons we can take for the future.

Joe Biden promised to tackle the climate crisis and address equity in transportation investments. Despite passing major legislation and hiring great spokespeople for reform, his administration did little to change the nation’s broken status quo. Here are the lessons we should take from this failure.

Talk does not equal action

The Biden Administration hired folks at USDOT who could speak eloquently about the need for transportation options and the system’s impact on the environment, both good and bad. Most notable was Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, whose oratory skills painted a picture of the multimodal transportation system we would build together.

But talk is not the same as action. Despite Transportation for America outlining 12 executive actions Biden could take without Congress, only two were implemented: repealing a Trump-era rule to make it easier to fund transit projects and supporting and implementing the Reconnecting Communities Program.

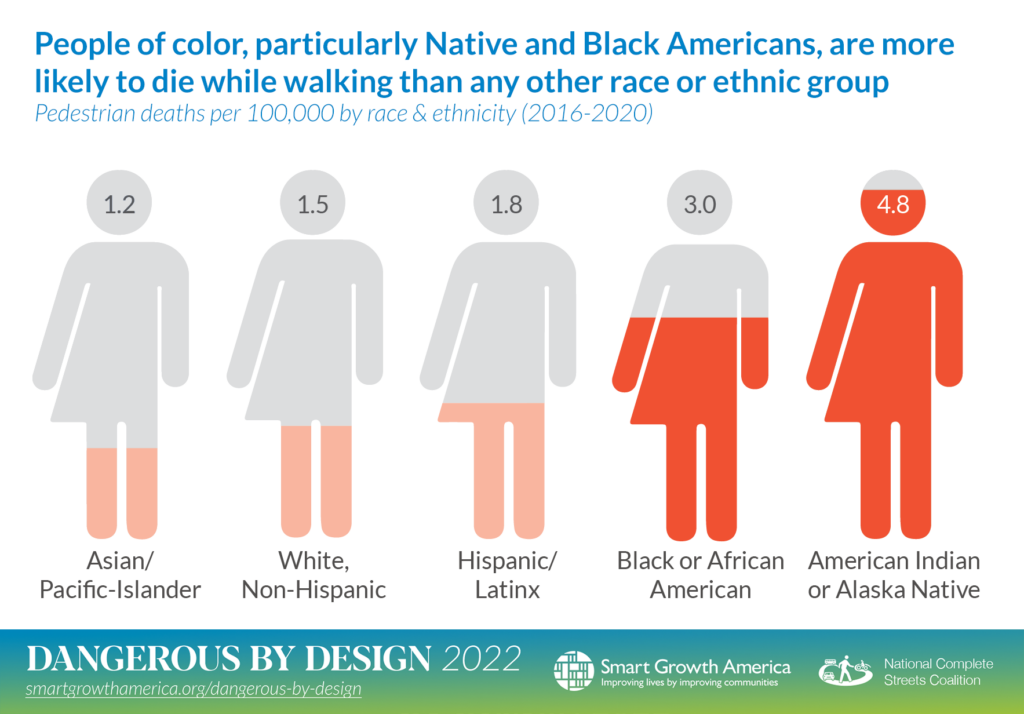

The administration left other priorities only partially completed. Reestablishing the greenhouse gas (GHG) performance measure for transportation was extremely slow, and they were unable to defend it from a court challenge. It took nearly four years to appoint a full Amtrak Board while failing to correct overrepresentation from the Northeast Corridor. Improvements to pedestrian safety in car and street design were modest, at best.

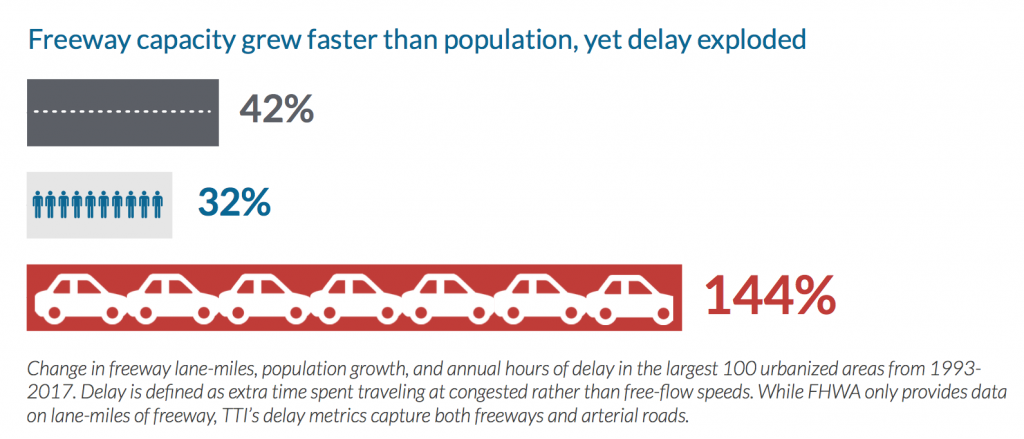

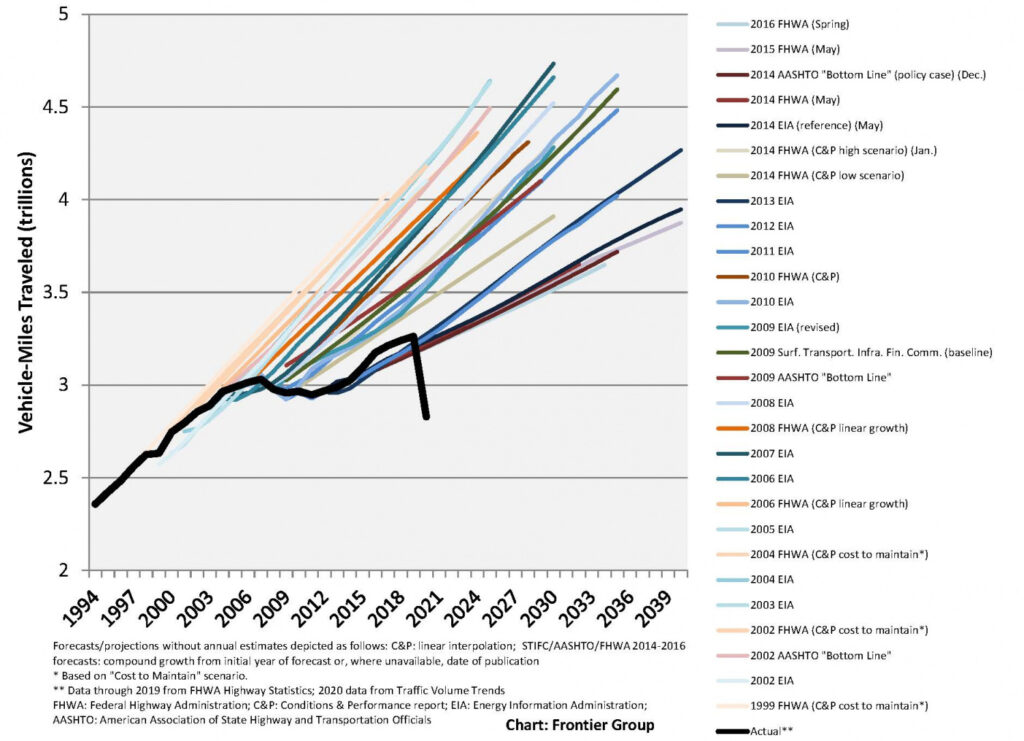

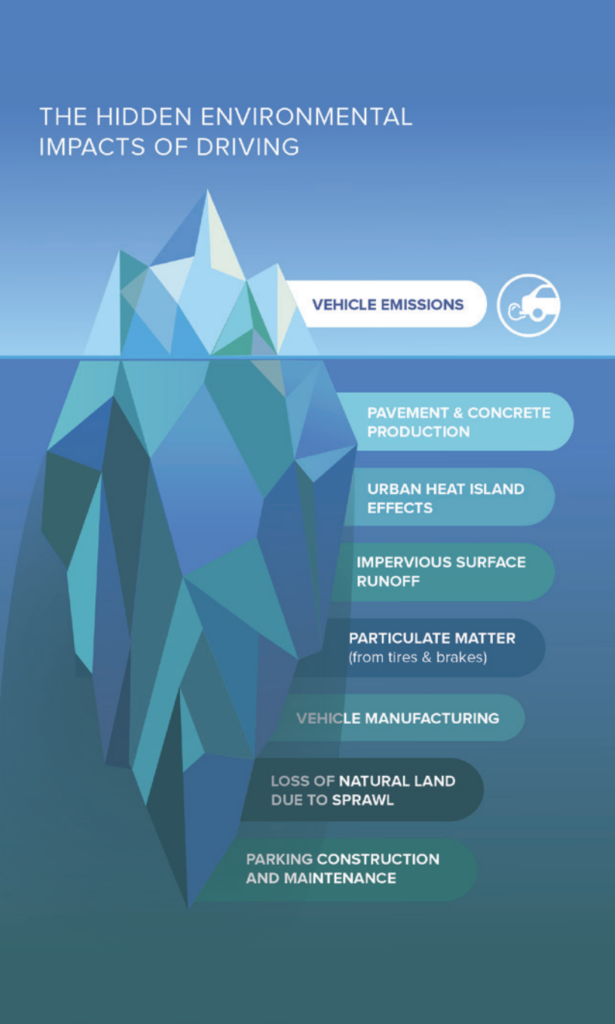

Another missed opportunity: some of the tasks they left untouched were more technical and likely to go unnoticed by political opponents, even though they would also have been extremely impactful for reducing greenhouse gas emissions (a goal the administration was explicitly committed to). Even as housing prices skyrocketed, the administration failed to revive the Location Affordability Portal and apply location efficiency and equitable development criteria to decisions involving the location of new federal facilities. The administration applied outdated, inaccurate, and inequitable value of time guidance to discretionary funding decisions focusing on vehicle speed without considering actual projected time savings for those traveling, whether they travel by car or use other modes of travel. They also failed to require the measurement of induced demand and review the accuracy of current travel demand models that are notoriously biased toward roadway expansion.

Fear of conflict is paralyzing

The administration shied away from the fights worth having (see our comments on the GHG rule above). An illustrative example was the saga of the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) memo asking staff to encourage state DOTs to focus on their repair needs, take advantage of the law’s flexibilities, and endeavor to reduce emissions and improve safety.

This nonbinding internal memo angered Senator Shelley Moore Capito (WV), who grilled Secretary Buttigieg in a 2022 Senate Environment and Public Works (EPW) hearing on the implementation of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). The crux of Capito’s opposition to the memo was the suggestion of a (non-existent) mandate and a one-size-fits-all context in the fix-it-first language. Despite Capito’s argument being wholly illogical—it was not a mandate—FHWA eventually replaced it with a memo that said FHWA maintained the same priorities but wouldn’t encourage the states to do anything to support them.

The real problem was this incident’s chilling effect. The conflict discouraged USDOT from taking other actions that might be met with objections. We’re left to question, if there is no opposition at all, are you doing anything that is actually meaningful?

Prioritize your priorities

What would eventually become the IIJA started as dueling proposals from the House and Senate. The House’s superior INVEST Act proposed bold, bipartisan reforms to the transportation program, prioritizing maintenance, safety, and access to jobs and services. However, the weaker text in the Senate’s version eventually won out, mainly due to pressure from the White House.

Additionally, the Biden Administration’s signature legislation continued a longstanding approach to fixing problems with the transportation system by creating small, discrete programs to fix problems that the much larger program would continue to make worse. For example, 9 percent of the highway program was dedicated to safety (6 percent to the Highway Safety Improvement Program and 3 percent to Transportation Alternatives). However, no policies, regulations, or standards were changed in the rest of the system, which meant we would keep digging that hole deeper.

The same is true in carbon emissions, with the IIJA leading to substantial emissions increases directly attributable to the bill. For the Reconnecting Communities program, funding went to projects that divided more communities than they were reconnecting. While the IIJA has provided immense funding overall, the legislation dedicated more money to the same old system and little funding to fix its problems. We got what Congress should have expected: more of the same.

Moreover, the separateness of the Administration’s new programs have made them that much easier to unwind and end.

Don’t over-process

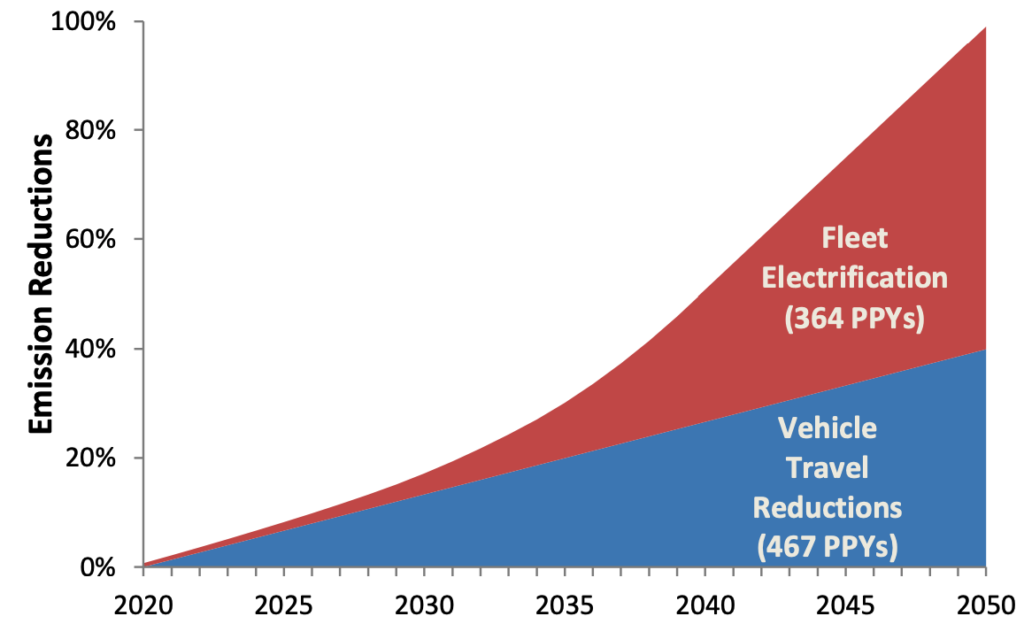

Another problem was the administration’s obsession with process over outcomes. The administration published lots of reports, guides, and best practices that hit all the right notes. For example, The U.S. National Blueprint for Transportation Decarbonization from the Joint Office on Energy and Transportation (JOET) masterfully describes the need for both electrification and improved transportation options to reduce GHG emissions from transportation. But it’s hard to say whether these reports changed how anything was actually done.

The administration’s obsession with process prevented it from simplifying grant applications, particularly grant agreement processes for the beneficial discretionary grant programs in the IIJA. T4America was involved in a grant agreement amendment process, which included multiple rounds of edits from more than a dozen editors, making a simple process long and complicated.

Combine this with the slow pace on rules for the new Carbon Reduction Program and the inflexibility and slow rollout of the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program, and you can see how there was little to show on the ground three years after IIJA passage when Biden’s Vice President stood for re-election. Now, Biden’s plans are being pulled down from government websites.

Make it hard to dismantle

We’re watching much of Biden’s signature policy achievements evaporate as the Trump administration takes actions (albeit many of them probably illegal) to set its direction on transportation for the nation. For example, three years into the NEVI program, only 200 EV chargers have been installed, and Trump is pausing the program. Even with more chargers in the works, it’s hard to imagine NEVI will produce the number of chargers needed to catalyze transformative electrification of our transportation system. On top of that, the administration failed to publish a map of where the planned chargers would be installed so that people would feel a loss if they were pulled back until after the election (instead, this was done by nonprofits T4America and Plug-in America).

Once something is built and operating, it’s harder to take away. The lack of visible impact not only weakens the case for keeping the programs but was inexcusable given the urgency of the climate crisis.

As excited as people were about the Biden Administration’s well-written plans and guidebooks, it is now clear how little of an impact they had as they are paused or removed from federal government websites.

Outcomes matter

The key lesson from all this is that outcomes matter, and you can produce outcomes by moving forward forcefully with purpose. An inclusive process can be helpful, but to ultimately serve people, especially disadvantaged communities, you need to deliver tangible results. We will look to work with this White House and Congress where we can find common ground on accountability, economic development, and safety. And we’ll be urging leaders at all levels of government who wish to advance a fix-it-first, pro-safety, pro-transportation options, smart growth agenda to focus on the outcomes they can generate under their purview during their term. American communities don’t have the time to lose on anything less.