America’s civil engineers raised the grade given to our country’s infrastructure from four years ago, but unfortunately, it’s still a failing grade for America.

With the $3.3 trillion dollars needed by 2020 (according to ASCE) unlikely to arrive in this current climate of reduced budgets and austerity, is there a way forward that can make smarter decisions with the money we have and knock back our maintenance backlog while still investing in the 21st century infrastructure our country needs?

The latest edition of the every-four-years report card from the American Society of Civil Engineers gives America a “D”, up from the “D-minus” we received in 2009. Improvement is always good, but a failing grade is still unacceptable, like a baseball player who hits a homer in a game his team loses.

“While our country’s association of civil engineers continues to do the yeoman’s work of sounding the alarm on our country’s infrastructure,” said T4 America director James Corless this morning, “it’s a sad reality that little has changed since the last Report Card in 2009.”

The truth is that few should be surprised at the state of things when they log on to the fantastic new ASCE interactive report card app (available on the web as well as for Android, iPhone and tablets) and sift through the national and state data.

Few would be surprised, because has anything here in Washington changed to drastically improve the condition of our roads, bridges and transit systems? Last summer, Congress finally passed a replacement to the transportation bill that expired just a few months after the last ASCE report card was issued — in 2009. Though a definite sign of progress in some areas, the new law provided no new dollars for transportation in the two years to come. The program dedicated to repairing our country’s 69,000 structurally deficient bridges was eliminated after making steady progress on reducing the backlog over the last 20 years.

Beyond the federal bill, which only represents about a quarter of all transportation spending, state and local revenues in many places are falling rapidly (MAP-21 held federal funding level at least) leading many Governors and state legislatures to float alternate plans for raising for revenue to make needed repairs and build anew.

While we certainly believe we need to increase the amount of money that we spend on infrastructure (especially transportation), simply increasing the amount of money is no panacea — ASCE is certainly right that we need to change how the money is spent — it’s not enough to pour more money into a cup with a hole in the bottom.

ASCE has some encouraging recommendations in this year’s report card moving the discussion in the direction of smarter, more transparent spending on infrastructure. We do need more leadership, more transparency, and a “focus on sustainability and resilience,” as they say in their recommendations. And we can no longer ignore growth patterns and things like a housing-jobs mismatch when making transportation decisions, affirmed by ASCE’s insistence that “infrastructure plans should be synchronized with regional land use planning.”

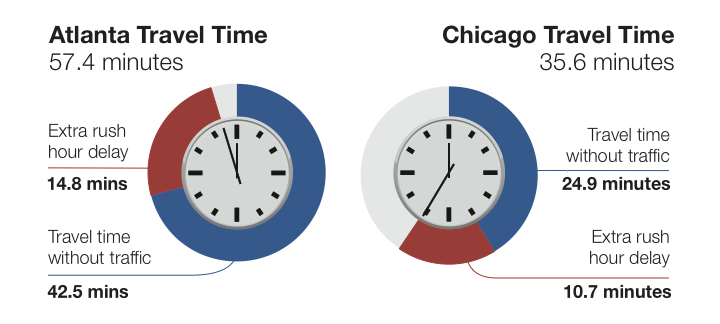

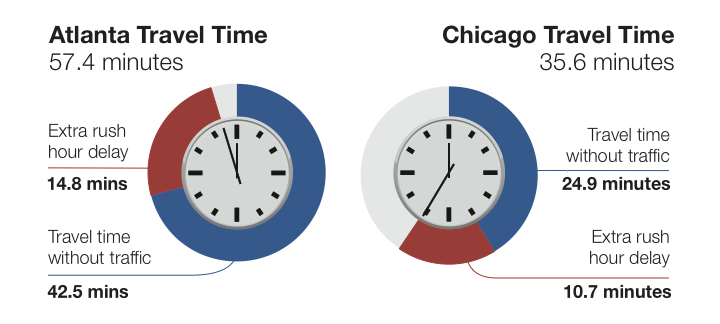

Some states aren’t waiting for billions that are unlikely to come and are already far ahead of the curve, thinking about ways to make their dollars do more. Like Massachusetts, where the DOT director issued a goal of tripling the number of trips taken by foot, bike and public transportation — reducing the load on roads and bridges that are among the oldest in the country. Or Tennessee, where the state DOT has taken a long look at their list of their proposed projects to see if they’re really necessary at a time when funding is dwindling, resources are scarce, and residents are looking for options to sitting in traffic.

Pushed between a rock and a hard place with forced austerity through reduced budgets yet being asked to do more with less, it’s time for a different approach.

With $1.7 trillion in needs by 2020 for surface transportation identified by ASCE and MAP-21 funding levels only due to bring in about $400 billion in that same time period, it begs the question: Who’s going to pay the difference? While ASCE avoids the question specifically, they do assert, much as we do, that there will continue to be an important role for the feds in planning and paying for infrastructure. “Federal investment must be used to complement, encourage, and leverage investment from the state and local government levels as well as from the private sector,” the report says. But it doesn’t stop there. “In addition, users of the infrastructure must be willing to pay the appropriate price for their use.”

Will we be willing to pay for what we need? Or do too many people think that we need to make the spending smarter before we make it bigger? However you answer, there’s not really an option other than smarter spending for the next two years, because MAP-21 didn’t provide any new money to states.

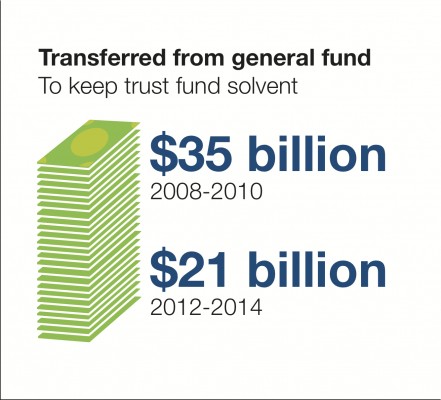

Yet MAP-21’s expiration is already on the horizon and the Highway Trust Fund is still headed towards its own fiscal cliff. The Senate budget resolution and the President have both suggested big increases in transportation spending. But where will the money come from? Despite key questions about where that revenue would come from, the simple fact that the 113th session of Congress has started with a number of proposals to increase investment in infrastructure, along with supportive comments from new House Transportation Chair Bill Shuster, have given transportation advocates a reason to be hopeful.

“With the federal gas tax bringing in less money every year, strong leadership from Congress is needed now more than ever,” said T4’s James Corless.

—

Some comparisons with 2009 at a glance:

- Bridges improved from a C to C+

- Rail improved from a C- to C+

- Roads improved slightly from a D- to D

- And transit was unchanged at a D

We’re no stranger at T4 America to the idea of using open government data to help ordinary citizens better understand their transportation system and how federal and local transportation policy needs to change to make them safer. We’ve regularly used public data from the U.S. Department of Transportation to seed useful tools, like the interactive map of ten years of pedestrian fatalities (

We’re no stranger at T4 America to the idea of using open government data to help ordinary citizens better understand their transportation system and how federal and local transportation policy needs to change to make them safer. We’ve regularly used public data from the U.S. Department of Transportation to seed useful tools, like the interactive map of ten years of pedestrian fatalities (