Ringling Bridge in Sarasota, FL. (Image: Rich Schwartz, Flickr)

Ringling Bridge in Sarasota, FL. (Image: Rich Schwartz, Flickr)

Thanks to support from the Kresge Foundation, Transportation for America helped several regions around the country take tangible steps toward aligning their spending with their policy goals using performance measures. We asked them about it…here’s what they said.

“If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.”

If that mantra ever needed to be applied anywhere, it’s in the world of transportation investment decision making. The state and regional transportation agencies that make funding decisions often say they want to fund the projects that best align with their community’s goals—such as increasing access to jobs and opportunity, improving health, making more equitable investments, and ensuring a good state of repair, to name a few. But too often, their practices don’t line up with intent. That’s why it is noteworthy that some regions around the country are making real headway to better align their spending with their stated priorities.

In a previous post, we explored this idea of choosing transportation projects that actually match our priorities. But what does it look like in practice to match funding decisions to a goal like economic competitiveness? And how is this process changing the transportation funding paradigm?

From the horse’s mouth

Rather than speak for them, we asked some of the professionals we worked with about how this assistance helped them address the specific transportation goals that their community is focused on. Each community has different goals, and the focus of our work shifted accordingly with each community, but the principle is the same: measure what you want to manage.

Reevaluating the status quo:

Typically, regions prioritize projects using factors like political priorities and geographic distribution, but this approach rarely produces the best set of investments to accomplish a long-term vision with limited funding. By contrast, some of the regions we worked with have established measurable goals and scoring systems to rank potential projects based on those goals. Many common policy priorities like equity and quality of life have traditionally been difficult to measure, so this systematic approach is a game-changer.

“In reviewing our past planning efforts we realized that there was not always a great connection between the projects selected for funding and our long-range plan’s goals. We also had more project requests than funding. Identifying performance measures and targets allowed us to prioritize the projects that would best help achieve our plan’s goals and make the best use of limited resources. T4America helped us refine our scoring process to ensure it was meaningful and performance-based, understood by non-technical stakeholders, and easily implementable by MPO staff.”

– Dylan Mullenix, Assistant Director of the Des Moines Area MPO

“The Lake Charles region is currently updating its long-range metropolitan transportation plan and will soon be selecting priority projects to fund. The Transportation for America team gave us ideas to simplify the measures used in project selection, eliminate duplication, consider the cost-effectiveness of projects, and make our scoring criteria publicly available. These suggestions and examples from other MPOs will allow the region to better prioritize projects based on a clear vision moving forward.”

– Cheri L. Soileau, AICP, Lake Charles MPO Director

Creating equitable and affordable transportation:

Equity was a common thread throughout this work. Many regions consider equity a priority, but have trouble effectively applying it to funding decisions. We helped these regions elevate needed investments in disadvantaged communities to improve access to economic opportunities and essential services. Some regions also wanted to prioritize investments that address community affordability. For example, the Sarasota/Manatee MPO hopes to raise the priority of projects that make it easier to walk, bike, and take transit to food, medical, or education facilities to help reduce the costs associated with accessing those necessities.

“Our partnership with T4A changed the transportation planning conversation in our region by bringing new voices to the table, from health and social service providers to environmental scientists. Using the FHWA performance measures framework, we have gone beyond traffic management and turn lanes to consider affordable housing, access to services for disadvantaged neighborhoods, and advancing best practices. We are confident this will lead to project priorities that consider all modes and that better serve all users.”

– Leigh Holt, Strategic Planning Manager, Sarasota/Manatee MPO

Supporting people who want to walk and bike safely:

Projects that make it easier to walk and bike not only improve the health of residents by providing options for exercise, they also support local economies by contributing to a quality of life that attracts residents and tourists. We helped several regions determine how to use performance measures to elevate the investments that make it easier to walk and bike safely.

“During Transportation for America’s workshop, the team encouraged us to renew our initiatives in active transportation for healthier communities. Our agency had developed a metropolitan bike and pedestrian master plan; however, as a result of the push, we began the process of actually producing every project in that plan. These 57 miles of active transportation improvements will be in place within the next six years! Furthermore, we are now replicating the same award-winning process in a neighboring urban area to further the goal of healthier communities through active transportation across our region.”

– Matt Johns, Executive Director, Rapides Area Planning Commission

Ensuring economic competitiveness:

Many regions measure their economic success by looking at how projects would reduce traffic congestion. But traffic congestion goes up with good economies and down with bad; so while it may be an important transportation priority, congestion reduction is not a good proxy for economic strength. We helped several of the regions determine how to use performance measures to invest in the right projects for the long-term economic vitality of their regions—projects that will help draw a talented workforce, retain residents, and grow a tourist economy.

“The Roanoke Valley Transportation Planning Organization is working to make the region more economically competitive by identifying places where growth is desirable and sustainable because plans for future development enable multimodal connectivity and mobility. The technical assistance provided by T4A helped us better understand performance measures and how we can more directly achieve our transportation and economic development goals through targeted investments.”

– Cristina Finch, Director of Transportation, Roanoke Valley-Alleghany Regional Commission.

These regions are able to make real change:

The six regions we worked with are already leading the way by seeking new ways of doing business. And thanks to Kresge’s support, we were able to introduce them to tools, approaches, and ways of thinking to help them do so. We are excited to see more innovative practices from these regions moving forward.

“The technical assistance provided by the Transportation for America team was more than a typical workshop—it opened the eyes of our local technical experts to a revolutionary way of thinking about transportation planning. We were taught how to better identify what problem we actually wanted to solve in order to avoid jumping to the usual prescribed solutions of cookie-cutter type thinking. In a way, the team provided a deeper validity and appreciation for REAL planning working in concert with engineering, and this is a necessity for better planning in an era when we truly cannot afford to “build our way out” of our problems.”

– Matt Johns, Executive Director, Rapides Area Planning Commission

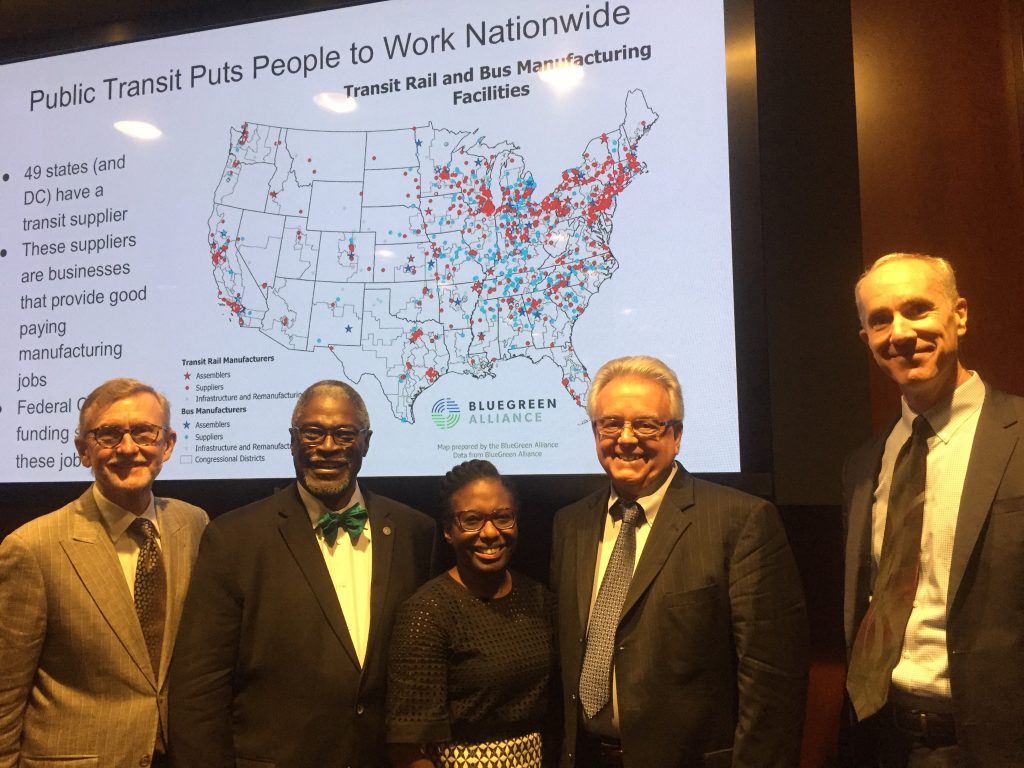

During a recent briefing on Capitol Hill, a panel of different stakeholders including the mayor of Kansas City spoke about the important national impacts that local transit investments have. While the mayor was in Washington, DC, Erika Young from Smart Growth America took a trip to Kansas City to see the local impacts of the KC Streetcar.

During a recent briefing on Capitol Hill, a panel of different stakeholders including the mayor of Kansas City spoke about the important national impacts that local transit investments have. While the mayor was in Washington, DC, Erika Young from Smart Growth America took a trip to Kansas City to see the local impacts of the KC Streetcar.

Hyde Park residents gathered at “The Heart of Hyde Park” free event to tell stories, write, and eat together to celebrate the existing community living in the neighborhood, share stories about the neighborhood, and to brainstorm ideas of what a better future for Hyde could look like.

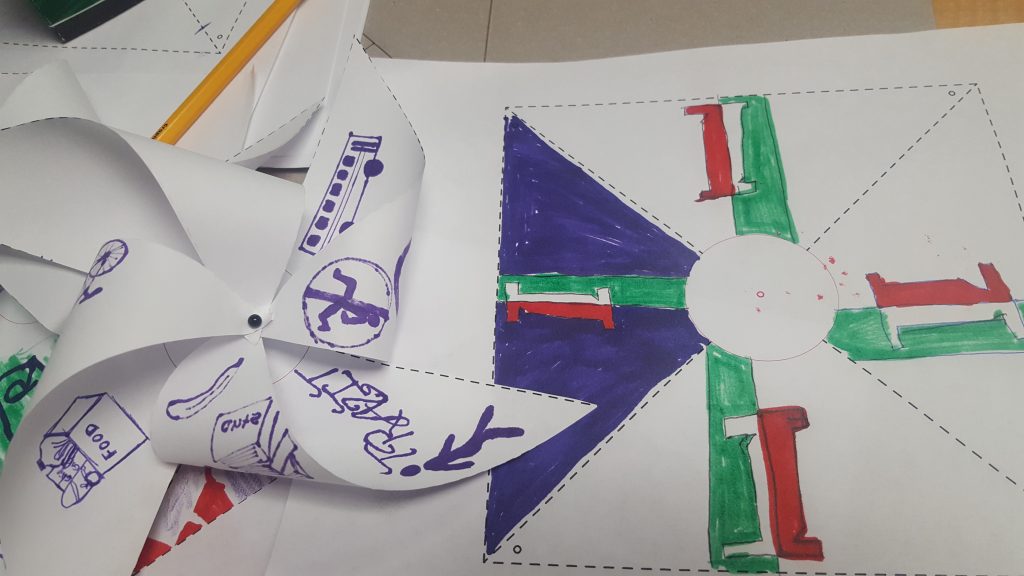

Hyde Park residents gathered at “The Heart of Hyde Park” free event to tell stories, write, and eat together to celebrate the existing community living in the neighborhood, share stories about the neighborhood, and to brainstorm ideas of what a better future for Hyde could look like. Purple Line artist, Wil Marquez of w/ Purpose, leads a workshop to make pinwheels as a tool to help communities think about how the upgraded transit system will improve their access to necessities and opportunities.

Purple Line artist, Wil Marquez of w/ Purpose, leads a workshop to make pinwheels as a tool to help communities think about how the upgraded transit system will improve their access to necessities and opportunities.

Atlanta is the perfect city to host the 2018 conference, as we’re making extraordinary progress on transit, place-making, and economic development.

Atlanta is the perfect city to host the 2018 conference, as we’re making extraordinary progress on transit, place-making, and economic development. The Metro Atlanta Chamber, along with many partners, has been working continuously to advance transportation and transit since we hosted the 1996 Olympic Games. Transit has played a huge role in helping Atlanta secure several major sports events, including the 2018 College Football Championship, 2018 MLS All-Star Game, Super Bowl LIII (2019), 2020 NCAA Final Four, and are among the sites to host games at the 2026 World Cup. Be sure to check out the College Football Hall of Fame, which is within walking distance of the hotel for the conference, or you can catch a ride on the Atlanta Streetcar.

The Metro Atlanta Chamber, along with many partners, has been working continuously to advance transportation and transit since we hosted the 1996 Olympic Games. Transit has played a huge role in helping Atlanta secure several major sports events, including the 2018 College Football Championship, 2018 MLS All-Star Game, Super Bowl LIII (2019), 2020 NCAA Final Four, and are among the sites to host games at the 2026 World Cup. Be sure to check out the College Football Hall of Fame, which is within walking distance of the hotel for the conference, or you can catch a ride on the Atlanta Streetcar.

Transit conference where all jurisdictions (save one) supported putting a measure on the November 2018 ballot to expand the Twin Transit district to include all of Lewis County.

Transit conference where all jurisdictions (save one) supported putting a measure on the November 2018 ballot to expand the Twin Transit district to include all of Lewis County.