The question to keep in the back of your mind as you read is this: After two years and more than $100 billion dollars, will we have made real progress on repairing our roads and bridges, making streets safer for all, and giving more people more options to get around quickly and affordably?

1. Incentivizing costly new construction, making repair optional

In our polling and conversations across the country over the last three years, Americans have said consistently, and emphatically, that Job One is keeping the roads and bridges we have in good repair. They also emphatically say we need a better range of travel options, and they’re voting with feet and fare cards: Record numbers of people are riding public transportation today, and demand continues to rise, with a corresponding rise in walking and bicycle travel

Unfortunately the new program doesn’t entirely match up with those impulses. MAP-21 encourages new highway Interstate construction by requiring states provide only five percent of the total cost, compared to the 20 percent they paid under the previous program. Other highways still require a 20 percent match. Transit projects, by comparison, are being matched at close to 50 percent by local taxpayers.

Although we have nearly 70,000 structurally deficient bridges and almost half our highways are rated below “good” condition, this bill takes a huge gamble by eliminating all money dedicated to repair.

Under the old law, states had to reserve at least 30 percent of their funds to fix roads and bridges, although even that was not enough to reduce the backlog. Now, repair of bridges and roads is purely optional, from a funding perspective.

States will be required to create plans, establish targets, and report on the condition of their infrastructure every four years. But the first report on those conditions won’t be due for almost six years, which means we’ll be waiting for four years after this bill expires to find out whether or not states with this new “no strings attached” approach has actually made any progress. That’s a big gamble on new and untested measures to take with some of our country’s greatest assets.

Even as some House Republicans were claiming that the tiny share directed toward safe walking and biking was the reason that our roads and bridges were crumbling, they were pushing to eliminate the repair program to fix our roads and bridges. The bill they negotiated ends up being as blasé about funds for maintenance and repair is it is about the safety of people on foot or bicycle.

2. Steps toward accountability for performance, but few teeth

The bill does take some steps forward in measuring the performance of transportation dollars. States and regions are required to set performance targets for highway and bridge conditions, freight movement, and safety; some regions are also required to look at air quality and congestion. After accounting for their current conditions, states and metros must tell citizens and local officials what progress their four-year spending plans are making towards their performance targets.

The bill does take some steps forward in measuring the performance of transportation dollars. States and regions are required to set performance targets for highway and bridge conditions, freight movement, and safety; some regions are also required to look at air quality and congestion. After accounting for their current conditions, states and metros must tell citizens and local officials what progress their four-year spending plans are making towards their performance targets.

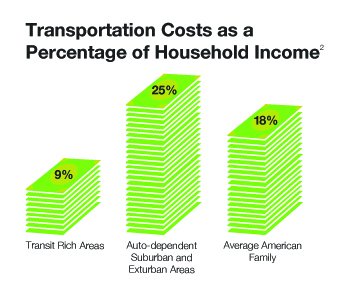

This is a good first step, but to create a truly performance-based system we must find ways to reward states and regions that set ambitious targets and make progress towards them. Another area for improvement is expanding the number of performance measures to examine other important areas like household transportation costs, energy security and access to jobs.

3. A false promise of “flexibility”

An oft-repeated refrain during debates over the bill was the need to provide flexibility to states to fund their most critical needs. However, this did not happen. Many of the provisions that would have provided increased flexibility were eliminated, such as the ability of states to invest in freight rail or local street networks. Provisions that would have provided local communities with the flexibility to use federal dollars to avoid cutting transit service and keep buses running during tough economic times were also eliminated. The perverse result is that communities will have the funds to buy new buses, but won’t have the money to pay someone to drive it.

The bill mandates that states spend nearly 60 percent of all funds on the largest highways, those in the National Highway System, leaving a heavier burden for the states and localities that maintain other critical links in the system. The most flexible pot of money – the Surface Transportation Program (STP) – now is responsible for covering more projects, but without a commensurate increase in funding. So while states will be able to use $10 billion to address a broad range of activities, they actually had more money and more flexibility under the previous bill.

4. Less money, but more local control, to make streets safer for all users

The bill eliminates the popular Transportation Enhancements, Safe Routes to School, and Recreational Trails programs and creates a new set-aside called Transportation Alternatives. While those three earlier programs totaled roughly $1.2 billion per year, MAP-21 cuts funding for the consolidated Transportation Alternatives by a third, to $808 million. There is some good news: 50 percent of that sum is allocated directly to larger metropolitan areas and other areas of the state with the capacity to plan and implement projects.

However, under a change made in conference, states can now transfer the other half to any other program. Under the bipartisan Cardin-Cochran provision passed in the Senate, this money was intended to be made available to smaller local communities via a grant program. If no communities wanted the money for biking and walking projects, as some lawmakers have repeatedly claimed is the case, then the state could spend that money on any other state needs. The change made in conference takes away local control and their local voice, declaring that the state knows better than your local community.

5. Continued funding of transit “New Starts” projects

The New Starts program, which funds almost all new transit construction, is retained and funded at $1.9 billion. Unlike highway funding, New Starts is subject to annual appropriations, just as it is today, and so is not guaranteed. MAP-21 does make several positive changes to the program. It simplifies the approval process and eliminates duplicative requirements. It also allows for “core capacity” projects to receive funding. Those are projects that, rather than building a new line, improve an existing line to move more people. This is becoming increasingly important as many systems across the country have lines at or over capacity.

“Corridor-based bus rapid transit systems” are also now eligible for grants under $75M. These differ from conventional bus rapid transit projects in that they do not need to operate in a dedicated transit right-of-way. This is a mixed development because it introduces a new eligibility that will compete with rail and full-fledged bus rapid transit projects.

6. More capacity to borrow, but less to innovate

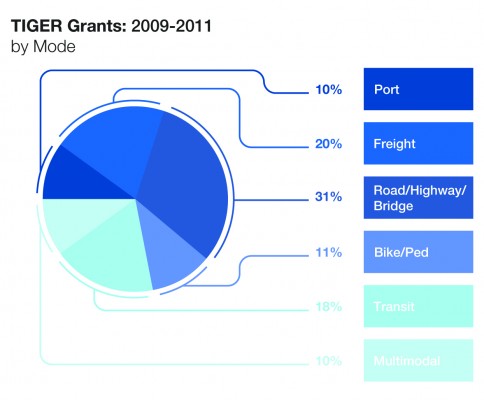

While the bill did not reauthorize the popular and over-subscribed TIGER grant program or establish a national infrastructure bank, it does include two expanded national infrastructure programs.

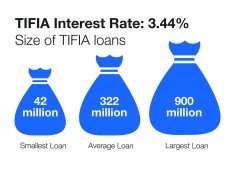

The TIFIA loan program provides low-cost loans – not grants — for highway, transit and intermodal projects that must be repaid. The program, which subsidizes low interest rates and provides federal guarantees, has been expanded from $122 million per year today to $1 billion in FY14, allowing U.S. DOT to support more than $10 billion in loans each year. (The program can support around $10 in loans for each dollar in funding.)

The TIFIA loan program provides low-cost loans – not grants — for highway, transit and intermodal projects that must be repaid. The program, which subsidizes low interest rates and provides federal guarantees, has been expanded from $122 million per year today to $1 billion in FY14, allowing U.S. DOT to support more than $10 billion in loans each year. (The program can support around $10 in loans for each dollar in funding.)

The expansion is good news to many places looking a way to make local dollars go farther, but the program has changed from merit-based allocation to first come, first served. The first creditworthy applications in the door — no matter what kind of project — will get the funding, skewing winners toward those with the biggest administrative departments (like state DOTs). That could mean that more complicated and innovative projects will go wanting after a long line of older “off the shelf” projects consume the available loans.

On the positive side, other changes do make it easier for transit agencies with dedicated local or state sales taxes to access TIFIA loans to improve their system, and a share of the money is reserved for rural infrastructure projects.

A reconstituted program called Projects of Regional and National Significance (PRNS) provides competitive grants for large highway, transit or intermodal projects typically with a total cost in excess of $500 million, or at least 50 percent of a state’s annual highway funding.

Though billed as a replacement for the popular TIGER program, it differs in critical ways, Unlike TIGER, local governments and metro areas cannot apply for the funding. Only states, transit agencies and tribal governments can apply, and port and freight rail projects are not eligible. TIGER was intended to fund innovative, cost-effective projects that were hard to fund under the previous transportation program — and they will be no easier to do under this new law.

This program is authorized for up to $500M in funding in 2013 and no funding in 2014, but like the New Starts program, it’s subject to the annual appropriations process, so it’s not guaranteed.

7. Transit stays in the trust fund, with more accountability for repair and safety

Under MAP-21, transit agencies for the first time will be required to measure the condition of their systems, set targets for improvement and report on their progress. Today FHWA has condition data for each half-mile segment of the Interstate system but there is no similar metric for the thousands of miles of transit.

The bill provides permanent authority to small bus operators in metro areas with fewer than 100 buses to use a portion of their federal funds to keep buses running. However, this authority was not extended to the larger transit systems, which have faced many of the same cuts and tough choices.

MAP-21 also:

- Consolidates programs focused on serving older Americans and the disabled, and increases funding

- Increases funding for rural transportation services

- Helps extend “last mile” intercity bus connections with private investments

- Does not require but allows states to spend funds on the Job Access and Reserve Commute projects

Communities that are building new transit systems or upgrading existing ones will also be eligible to apply for new planning grants to help them efficiently locate jobs and housing near new transit stations, boosting ridership and increasing the amount of money gained back at the farebox.

8. Multiple changes to environmental and citizen review, with unpredictable impact

The bill makes many modifications to the project review process in hopes of speeding up the construction. While this is certainly a goal worth supporting, many of the new changes damage the ability of local communities to have a voice in projects that will have enormous impacts on their quality of life, air and water.

There were a large number of changes made to review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) after significant focus and debate in conference, but here are a few of the key changes:

- Projects built on land already owned by a state DOT do not have to undergo reviews for impacts on the environment, neighborhoods and health before they can move forward – so a state could double the size of road without public input on the impacts and different solutions

- Also exempted from review are projects that either (i) cost less than $5 million or (ii) that are less than 15 percent federally funded and cost less than $30 million.

- States can take over the review process from the federal government if they have state laws that are similar to federal laws. California did this in 2007 under a pilot program that is now a permanent program.

- Allows states to avoid analyzing alternative solutions if their preferred solution was already analyzed during the long-range planning process. Basically it allows a DOT to say, “I’m building a highway from A to B”, put it in the long-range plan, and never look at whether or not transit would have been better.

- Takes funding away from resource agencies – up to 7% of the approving office’s budget – if they do not complete their reviews under new deadlines.

It remains to be seen how these and the other major changes made will impact the speed at which projects are built. Will they help speed up construction, or engender a backlash from citizens and stakeholders who feel shut out of the process? Will bureaucrats move faster to review projects, or will short-staffed agencies simply feel forced to reject good projects to meet a response deadline and keep their funding?

9. For rural communities, a seat at the table and a focus on the most dangerous roads

Many rural communities feel run over during the statewide planning process with little concern or consideration given to their needs. MAP-21 changes the planning law to give these communities a seat at the table during the planning process. It also authorizes the creation of Rural Transportation Planning Organizations to ensure that they can meaningfully participate at the table – though the decision to create these rests with each state.

The new law also takes steps to ensure rural safety needs are addressed. First it requires states to use crash rates, in addition to crash frequencies, to identify and target areas for improvements. This will help rural areas as they do not have as many crashes but often have much higher rates. It eliminates the high-risk rural roads set-aside which states often did not spend and replaces it with a “pop-up” penalty, so if fatalities on rural roads increase then states must spend at least twice their former high-risk rural roads set-aside to improve safety on those roads.

10. Tolling for new interstate lanes with an HOV sleight-of-hand, and an emphasis on public-private partnerships

Today states are not allowed to toll Interstate highways except under very limited and rare circumstances. MAP-21 allows states to toll any new Interstate lanes – as long as the number of free (non-tolled) lanes, excluding high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes, remains the same. This misses a major opportunity to allow states and regions to advance congestion pricing and other user-based charges that could both generate revenue and tackle traffic on clogged urban interstates.

Under the old law, states that converted free HOV lanes to “high-occupancy toll” lanes – where solo drivers can pay for access — had to use the associated revenue primarily for projects that provide alternatives to solo driving. Now, states will be allowed to build any type of project with those revenues. Ironically, many HOV lanes were built with Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality funds expressly dedicated to providing alternatives to solo driving. The new law allows states to build HOV lanes with clean-air funds intended to reduce solo driving, and then convert those lanes to toll lanes whose revenue can be used to build new lanes for solo driving.

The bill also requires DOT to develop best practices for public-private partnerships, including information on policies and techniques to protect public and state and local government interests. P3s, as they’re known, are touted as a potential new source of funding for transportation projects. FTA is required to identify impediments to P3s for transit projects as well as ways to improve transparency.