With the help of representatives from two cities, T4America staff a few weeks ago walked through our new Playbook for effectively managing shared micromobility services like dockless bikes, electric scooters, and other new technologies.

Flickr photo by Daniel Lobo. https://www.flickr.com/photos/daquellamanera/38503203635/

Almost overnight, shared scooters and bikes have rapidly proliferated in cities across the country. T4America’s new Playbook for Shared Micromobility is helping cities find their footing. We walked through the new guide a few weeks ago in an online presentation. (Watch the full presentation here)

Our sincere thanks especially to Francie Stefan (Santa Monica) and Josh Johnson (Minneapolis) for their time and especially for openly sharing about their experiences and lessons learned so far. Here’s a collection of some of the questions we weren’t able to answer during the presentation, compiled from T4America staff with input from our guests. Any mistakes or errors are T4America’s alone.

GEOFENCING

Is constituent/resident input considered when forming geofencing?

Cities should engage constituents including residents, employees, businesses and visitors when considering the boundaries for operations as well as any specific areas where operations would need to be controlled in a different way, including restrictions on operations, specific parking areas, or speed differentials. Cities and operators together will need to work together to ensure an appropriate level of engagement, communication, and education around these areas.

In Minneapolis, public input was actually the primary consideration for 2018’s geofencing (of two areas), based on feedback received via our 311 system. Going forward in 2019, Minneapolis’ intention is to tie the monitoring interface with daily mapping of 311 complaints and try to more quickly react or anticipate where it is needed.

We have a policy in our city that does not allow any e-bikes or pedal assist bikes on any of our greenways or trails. How can geofencing help us avoid constant issues with e-bike use on the greenways?

At least thus far, geofencing technology for many devices has not always been precise enough for detailed enforcement. Improved equipment could address much of the issue but is not widespread. But geofencing can help alert riders to operating restrictions in specific areas. Larger areas with buffer zones around them like a trail system may be large enough to enable geofenced speed reduction, parking prohibition, or other tools. Robust communications by the city and in-app by operators can help deter riding or usage in restricted areas.

How well did the geofencing technology work? In Santa Monica, specifically in restricting devices from working in specific areas (Santa Monica city vs Santa Monica College).

The geofencing is working well in larger areas like the Marvin Braude Beach Bike Path. That zone is wide enough to enable effective location-based speed reduction down to 5 mph for all scooters. The city works regularly with the operators to ensure that all versions of the devices are set up to reduce speeds, and to ensure that parking limitations are in place.

FEE STRUCTURE

Good protected infrastructure is very important for shared micromobility users, but it’s also a vital element of more sustainable and equitable cities, whoever ultimately owns the vehicles. What is the fair share for micromobility providers to pay, given that more active transportation is already an element of most T4A cities’ transportation goals?

Unfortunately there is not a clear cut answer at this point, however Minneapolis is exploring a research project to determine the fair share across all shared modes. In the meantime, we are thinking about the infrastructure portion of fees related to costs of improving the existing system to more comfortably accommodate new modes through added bike lane protection (delineators), markings/signage, and additional striping for parking zones.

Santa Monica adopted an interim fee that was calculated based on the PROW square footage used by devices. The study looked at the average footprint of a device in the PROW when stationary (bike/scooter/vertical/horizontal), and then applied the per-square foot fee used for outdoor dining in the PROW. The staff report for fee adoption can be found here.

Do you see cities moving from a fee structure to a subsidy structure for these services? Shifting to a higher penalty for SOVs and rewards rather than fees on lower-emission modes.

Given the ongoing debate in cities across the country and how to appropriately tax and levy fees on everything from TNCs to micromobility operators to freight and urban delivery to private vehicle use, it’s still unclear how to best assess the impacts of various transportation users and service providers on our shared infrastructure. Ultimately, T4A would like to see fair user fees supported across all modes that truly represent the positive, and negative, impacts of each user and use case.

What is a reasonable cost that cities can expect to spend as a result of allowing dockless vehicles/shared micromobility to operate in their cities? (Including everything that goes into it: reviewing permitting applications, dealing w/ picking up rogue vehicles if the operator does not, etc.)

These new services are in their infancy and the exact costs that are being borne by cities to administer and manage them are not yet clear. In developing an overall fee structure, cities will need to think holistically to calculate the full and actual costs—including everything from staff time to software management platforms to daily operational needs to outreach and engagement. While cities can take some cues from each other, these costs also vary from city to city given the nature of their regulations, labor costs and other local factors. Conducting a cost analysis study can help determine the true costs.

FLEET SIZE

Should there only be a single operator per community or can there be competition in this arena? Also should a cap be set for the industry or individual operator?

It’s still unclear what an appropriate number of permits or overall fleet size should be as it relates to population, density or other community factors that will appropriately serve individual communities and the city as a whole—while still creating an attractive and profitable market for operators. Between permit caps and fleet size caps, cities should probably focus more on managing the overall fleet size effectively to create a program the whole community can benefit from. Cities should use dynamic, performance based caps that establish clear, utilization-based formulas for the expansion of operator fleets.

Minneapolis is also thinking about—in terms of the differences among companies—whether it’s a different product (such as a sit down scooter) or potential differences in operating structure (vendor hiring practices, fleet activities, etc.) and also how closely vendors align with city goals for transportation and mobility. With rapid growth and continued consolidation in the scooter industry, there is also the idea of maintaining continuity of service, should a vendor be acquired or leave the market.

How did the City of Santa Monica decide on their initial fleet size for providers?

In Minneapolis, any hints on the actual ratios of people/scooter you’re examining? Any preliminary findings you can share on those numbers? Formulas?

Santa Monica interviewed eleven operators before crafting the the scope of the pilot program and Administrative Rules. One of the questions asked was regarding the optimal number of devices with which to start operations of a fleet that would serve the whole city. Answers all hovered around 500 devices, and there was interest in flexibility. That informed the starting point for the pilot program. The city has owned a 500-bike bikeshare fleet since 2015, and it has worked well for the city’s size and layout.

In thinking about ratios of people per scooter, Minneapolis has been discussing and comparing with a variety of other cities, and comparing that to last year’s results based on the population that was generally served by the distribution of scooters. Minneapolis is also talking to some of the vendors who’ve expressed interest in Minneapolis to see how they determine ideal fleet size. Those calculations are still being firmed up but Minneapolis is hoping to use 2019 as the starting point to establish the idea and then evaluate performance from there.

INFRASTRUCTURE

I would love to hear more about the Minneapolis idea of dedicated fees to advance protected bike infrastructure! Did you set up designated parking areas for scooters anywhere? Does the $1/day PROW fee fund something related to streets (or even active transportation infrastructure?)?

Minneapolis has set aside the fees from the 2018 pilot and is thinking about establishing some testing of this idea in 2019 in places with low-hanging fruit such as adding delineators on bikeways (with no current protection) which connect equity focus areas to core parts of the city. Minneapolis is also looking at testing lane markings and dedicated parking, particularly in dense areas with narrow sidewalks. Equally important to this effort will be communication of how and why this is being done.

EQUITY

Were these set up with any particular group in mind? Are these focused on ensuring the best interest of the broad public and of special-needs group?

The was developed as a result of a collaboration between Transportation for America and the participant cities in T4America’s Smart Cities Collaborative as well as industry stakeholders including Lime. T4A conducted additional research and held conversations with cities across the country developing regulations and managing pilot programs. The Playbook also builds on the effort by the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) and their member cities to develop their Guidelines for the Regulation and Management of Shared Active Transportation.

DATA

How do you think about requiring operators to provide public feeds in GBFS format so real-time info is visible to the public and trip-planning apps? These feeds were missing in some early pilot programs, but cities like DC require them from new mobility operators, which are already commonplace for existing systems like Citi Bike, Breeze bikeshare and Nice Ride MN.

This is perhaps a notable difference between a publicly owned and operated system (often through contract) and a service that’s privately owned and operated. Systems owned and managed by public entities (such as those listed in the question above) have mostly been making their data publicly accessible. But, while some cities are requiring data be provided by (private) dockless operators, not many have required it to also be publicly available. So far, private operators have typically been comfortable sharing data with regulators for enforcement and operations, but have been opposed to being required to share their data publicly to the benefit of other private sector companies.

PERFORMANCE METRICS

Are there recommendations for the most effective performance metrics?

Great question! We include a list of potential metrics that cities can use to measure performance in the playbook. But, given that we’re still very early in the development of these services, it’s not clear yet which metrics may be best. And, since each city will likely have different goals and outcomes that are most important to them, it will be important for each city to determine which metrics best track the outcomes or impacts they’re most interested in.

Relatedly, that type of ethos governed our overall approach to the playbook. T4America wanted to provide a framework that any city could use to advance their specific goals, while also recognizing that cities will bring vastly different big-picture goals to the table. Some cities might be more committed to shifting more trips to cleaner modes, for example. The important thing is for cities to understand how measuring performance is (and should be!) connected to accomplishing specific goals, and then to find the metrics that best get them where they want to go.

Question for Minneapolis: How would your population density-based distribution requirement work?

This idea is still being explored in Minneapolis, but essentially it would be establishing a goal ratio of people per scooter, based on population and including commuters as well as students (where applicable) to try to include the groups using scooters regularly. That would then be used to establish some distribution minimums or maximums, to ensure broader distribution and availability. Minneapolis essentially allowed the market to determine distribution in 2018, and we are thinking about how we can make it more equitable and position it as an option for all in 2019 and beyond.

GENERAL

For cities that have conducted RFA/review processes for selecting operator companies, what criteria is used (metrics, performance measures, etc.) have been used to rank, evaluate, and determine which company is most competitive and also the best fit for both the city and the overall community?

Last summer, the San Francisco San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) created its Powered Scooter Share Permit and Pilot Program. Their application process invited proposals that prioritized the city’s concerns around safety, equity and accountability and they rated everything from public safety and user education to equitable access to collaborating with the city. You can find the details, applications and their public review on their website.

The enabling ordinance for the pilot project specified some of the selection process, including “Each qualified applicant shall be evaluated based upon objective criteria including: experience; proposed operations plan; financial wherewithal and stability; adequacy of insurance; ability to begin operations in a timely manner; public education strategies; relevant record of the applicant’s or officers’, owners’ or principals’ violations of Federal, State or local law, or rules and regulations; and any other objective criteria established by Administrative Regulation.”

Minneapolis : How is your ridership in winter versus summer?

Minneapolis didn’t get much snow or ice in November prior to the end of the pilot last year, however temperatures did drop in the last 3-4 weeks of the pilot, which caused a steady decline from roughly six trips per scooter per day to about three trips per scooter per day by the last week. At the peak in early summer, we were seeing about seven trips per scooter per day.

Is Santa Monica’s eScooter industry review publicly available? If so, could you share it?

All available program documents are posted here.

What is a typical day-in-the-life of your Code Enforcement Officer?

Code enforcement tasks are both in the field investigating issues and documenting conditions, as well as in the office responding to phone calls, e-mails, and submitted complaints. Time is split roughly 50/50 between field and office, inclusive of work entering reports and evidence into a document management system in the event that a complaint ends up in a hearing. Code staff investigate complaints in the field, and if confirmed will follow up with additional investigations which may lead to citations from violated municipal codes. Once a complaint is confirmed, code staff investigate the problem daily or even weekly until the problem is resolved.

—

Thanks again to our guests for their time. View the full Playbook at playbook.t4america.org

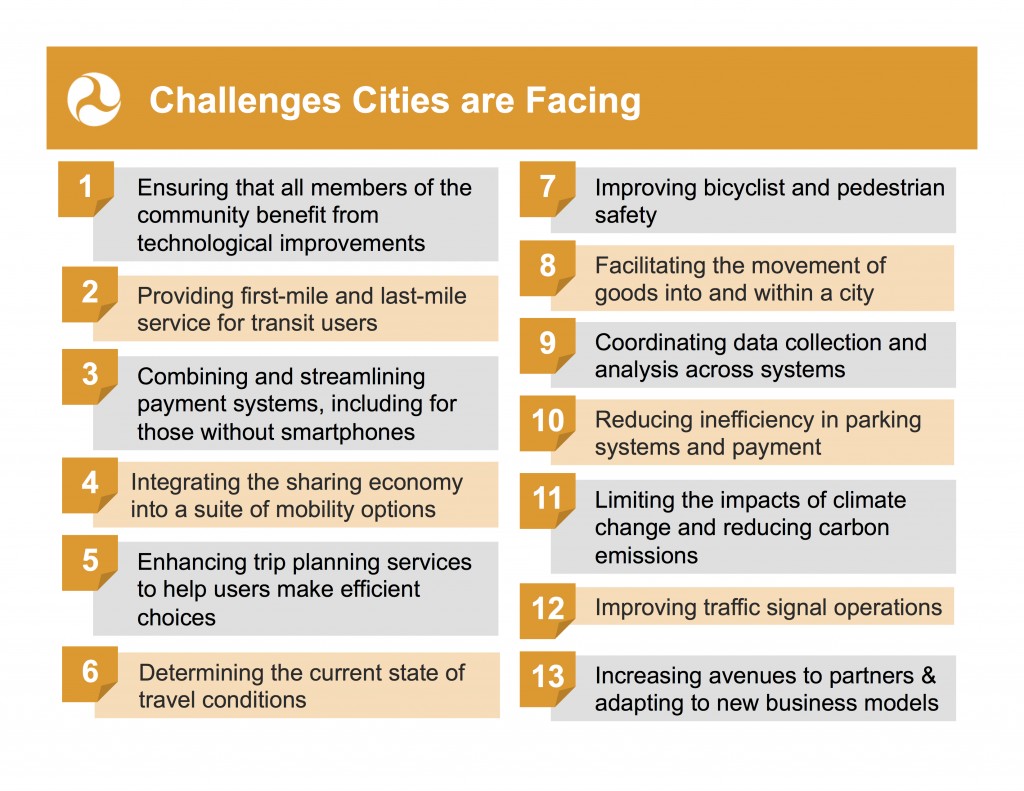

No cities were even considering the prospect of shared electric scooters two years ago, and now in 2019, hundreds of them are. This incredibly rapid pace of change is unlikely to slow anytime soon, and it highlights the need to create flexible regulatory frameworks that will help cities integrate new technologies and contribute toward their preferred long-term outcomes.

No cities were even considering the prospect of shared electric scooters two years ago, and now in 2019, hundreds of them are. This incredibly rapid pace of change is unlikely to slow anytime soon, and it highlights the need to create flexible regulatory frameworks that will help cities integrate new technologies and contribute toward their preferred long-term outcomes.

Much of that conversation centered on how cities can drive the discussion and lead at the state level on those policies that will have the largest impact on our cities. Keynote speaker Seleta Reynolds, the head of the LA Department of Transportation, reminded the participants that, no matter what policy levers are controlled by the state, cities still have an enormous amount of leverage — if they’re willing to work together and think outside of the box.

Much of that conversation centered on how cities can drive the discussion and lead at the state level on those policies that will have the largest impact on our cities. Keynote speaker Seleta Reynolds, the head of the LA Department of Transportation, reminded the participants that, no matter what policy levers are controlled by the state, cities still have an enormous amount of leverage — if they’re willing to work together and think outside of the box.

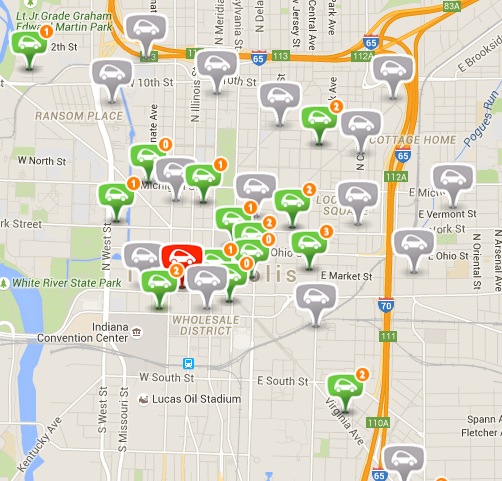

The system is launching with 50 vehicles and 25 charging stations (doubling as the reservable parking spots) around the city, with a plan to soon expand up to 500 electric cars and 200 stations. The city is paying $6 million in dollars earmarked for infrastructure projects, with the French company that owns the service investing somewhere over $40 million.

The system is launching with 50 vehicles and 25 charging stations (doubling as the reservable parking spots) around the city, with a plan to soon expand up to 500 electric cars and 200 stations. The city is paying $6 million in dollars earmarked for infrastructure projects, with the French company that owns the service investing somewhere over $40 million.