Last week in Atlanta, Georgia we wrapped up our second cohort of the Smart Cities Collaborative with the fourth meeting of 2018. Once again, staff representing cities, counties, transit agencies and other public sector agencies from 23 cities gathered together to share their experiences and learn how others are using technology and new mobility to become better places to live. Here are seven things we learned or heard last week.

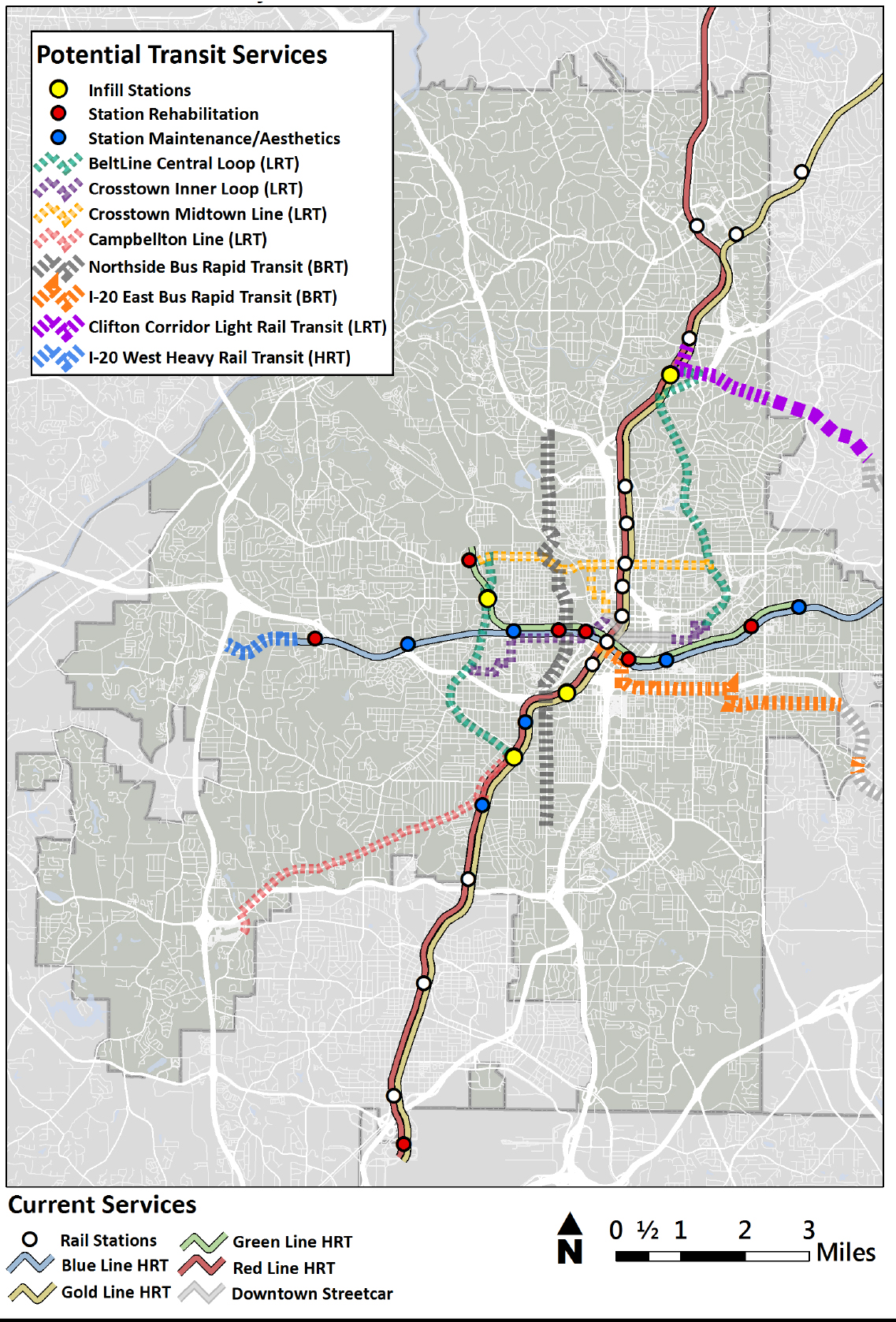

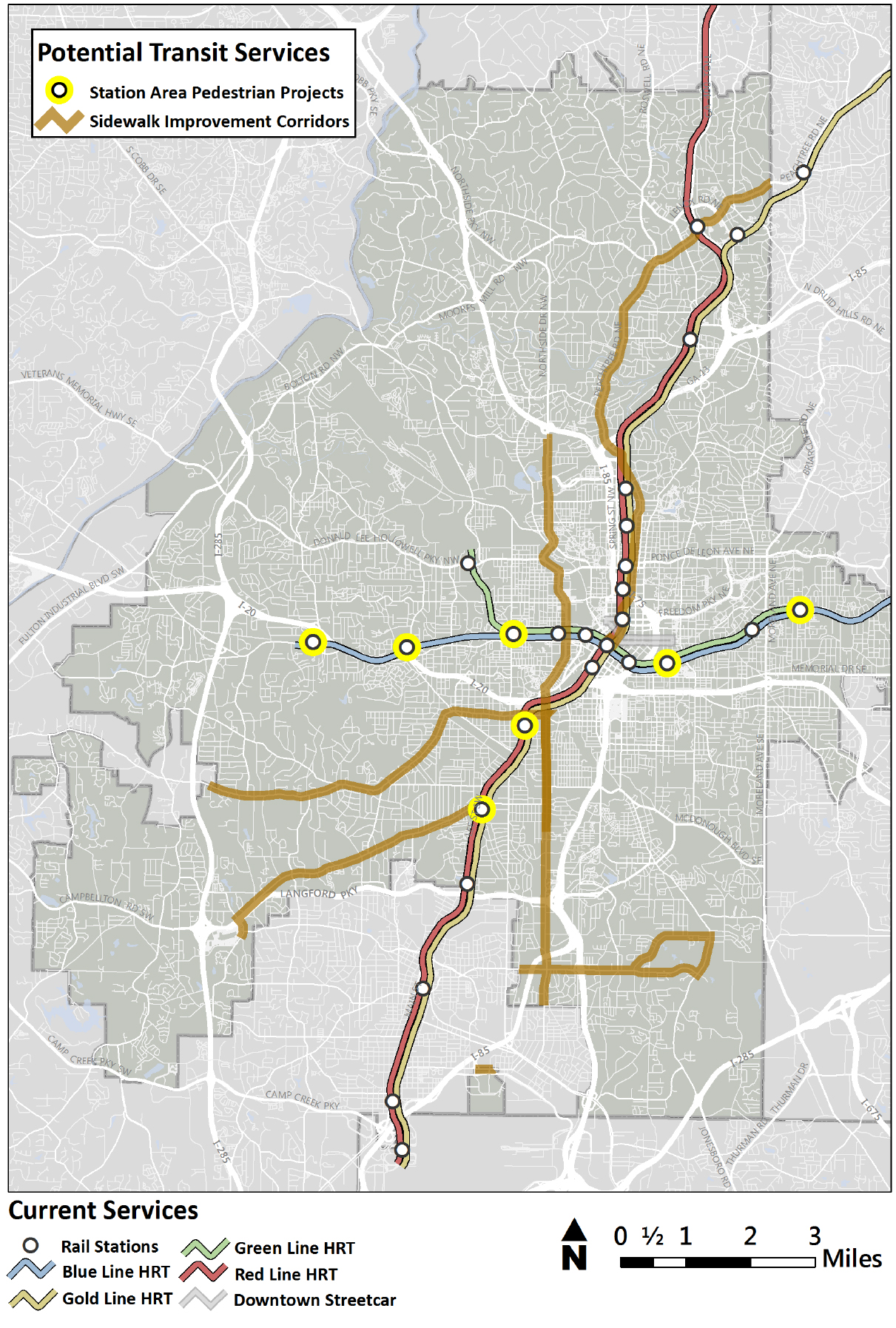

1. Atlanta has a tremendous amount of momentum and potential

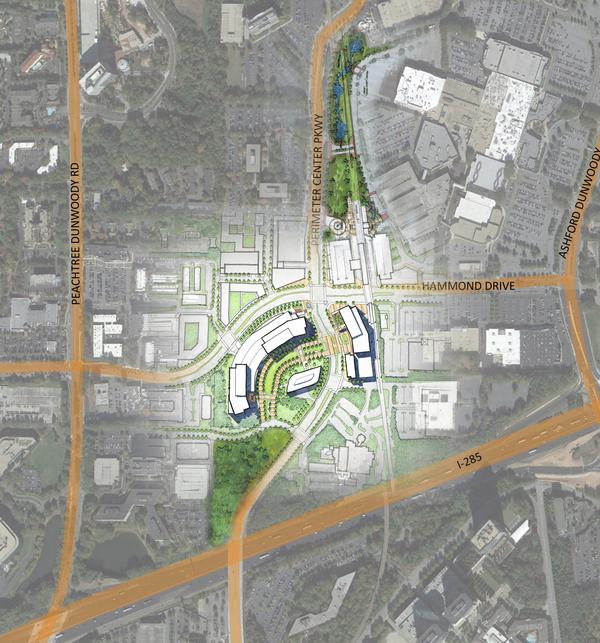

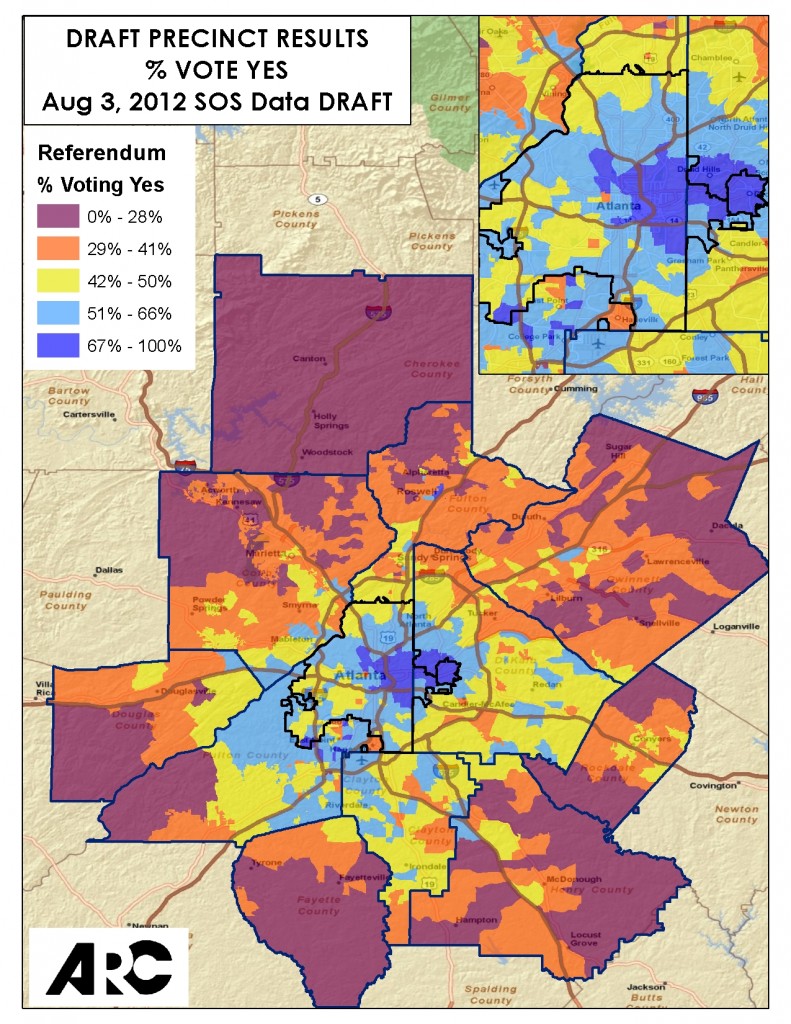

As someone said during the week at one point, it’s much harder to affect significant change if you’re not growing, and Atlanta (both the city and the region) have been booming. In fact, after losing population for nearly thirty years, the rate of population growth in the city proper has been near the top of the list within the (massive) region over the last few years. Which also means that the city and region alike are struggling to keep those people moving and well-connected to jobs and opportunity. Atlanta City Councilman Amir Farohki and Planning Director Tim Keane shared a little of the Atlanta story and how they’re working hard to keep people and residents at the center of their city’s efforts to improve mobility and access.

Atlanta Councilman Amir Farokhi, left, and Planning Director Tim Keane speaking to the Collaborative in Atlanta.

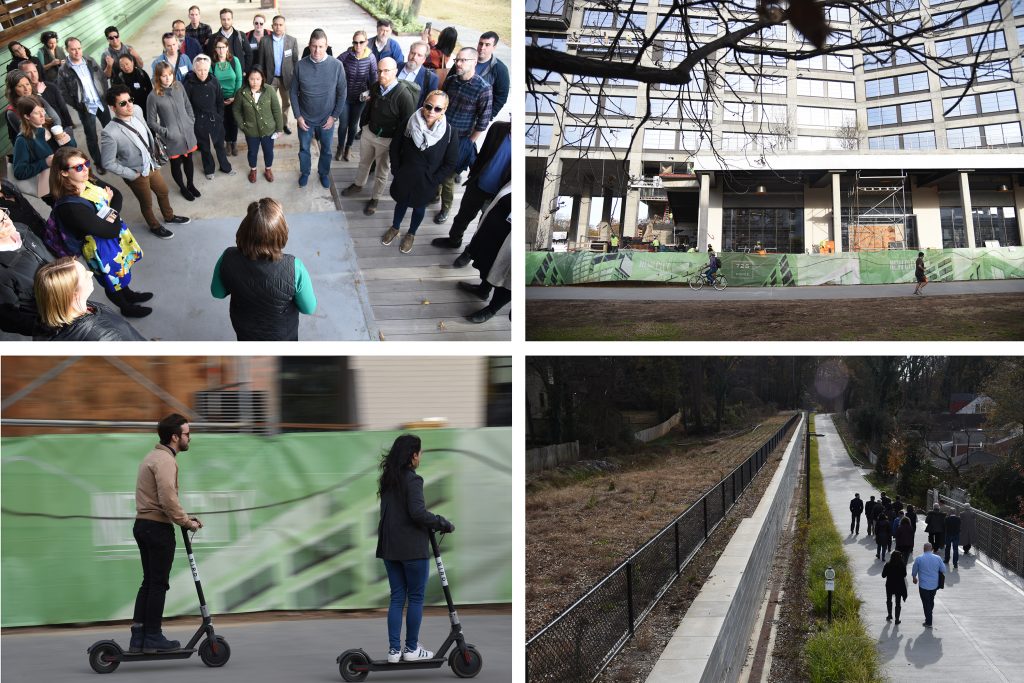

One of the best illustrations of that effort is the Atlanta BeltLine, an unprecedented and multi-decade project to add trails, parks and transit to old railroad corridors that form a ring around the core of the city. We were fortunate enough to get out of our meeting space in downtown (provided by the Atlanta Regional Commission) long enough to get a terrific tour of a small portion of the BeltLine, and it’s truly a transformative, people-centered project that will have immense long-term benefits for the city.

Touring the Atlanta BeltLine with staff from Atlanta Beltline near the Ponce City Market on the city’s east side, and on bottom right, touring a just-opened portion of the west side trail with the portion set aside and prepped for transit on the left side of that photo.

2. This was the last meeting of the second cohort of the Collaborative

This meeting wrapped up our second yearlong cohort of the Collaborative, putting a bow on a year that kicked off with 23 cities in Denver way back in the spring, traveled to Seattle over the summer, and then met in Pittsburgh near the beginning of the fall. We’re planning to reflect a little more later on in another post about a year spent learning with these cities, but suffice it to say we covered an immense amount of ground over a net total of only about a full week of time together, and we will miss working together with them every few months.

3. Arcadis sponsored the meeting and made an interesting offer to the cities

Data. Daaaaaaaaata. We all hear about it nonstop.

And it’s true: new technologies and mobility options are providing a wealth of detailed, real-time transportation data to planners and managers across the country. This is creating new opportunities to analyze historical data and better measure operations, understand network conditions and trends, and ultimately help cities make better decisions about how to manage their transportation networks.

But, despite all this wonderful new data, most cities haven’t been able to fully realize its benefits, update their models or turn it into meaningful action. It’s certainly possible to use this data to better understand what’s actually happening on the ground with present and future travel demand, but it’s a tough job for any city—especially the small and mid-sized cities—to do this on their own.

Arcadis, a large global planning and design firm that sponsored this meeting, came with an interesting proposal: They offered a three-month data analytics pilot project of nearly any kind to Collaborative cities for free. But they don’t want to just roll ahead with an idea of their own—they wanted to collaborate and work together with cities to figure out what would be most helpful. So their team, and others from Sam Schwartz Engineering, HR&A and Cityfi, met with the cities in small groups for a half-day to better understand their specific challenges and identify key areas to include in potential data analytics pilots, craft the scope for coordinated pilots across multiple cities, and highlight a few options for differing outcomes in each community.

4. We heard a lot about tangible projects happening on the ground right now

The Collaborative has always intended to be about action and real, tangible efforts to improve mobility and experiment with new technologies and tools. While a lot of our time was taken up with some big picture issues, we also heard short presentations from other cities that are forging ahead about how specific pilot projects are faring, with the hopes of sharing lessons and experience with the other cities that might want follow—or chart their own path.

Dan Hoffman from Gainesville, Florida shared about the automated vehicle shuttle pilot that they’re hoping to get rolling in early 2019. He explained the goals of the pilot, where and how it will operate and all of the hurdles they’ve cleared along the way to try to put a real AV shuttle on the ground connecting downtown and the University of Florida, providing a useful test case for other cities hoping to obtain a NHTSA waiver for AV testing or how to partner effectively with the state.

Robin Aksu from the Los Angeles Department of Transportation also joined us to speak on mobility hubs and how their project is progressing. Robin shared what they’re hoping to accomplish by creating mobility hubs, the focus on primary and satellite hubs and how the design will reflect those differences, and how they’re approaching implementation along with communications, marketing, and their community outreach program.

Mark de la Vergne from Detroit, Michigan joined us to share more about Night Shift and some of their other transit programs. Night Shift is specifically designed for late night and service workers to help connect them to transit and improve access to jobs. Mark shared about the process his team has gone through to conduct engagement and outreach in their local community to not only design the service, but ensure it meets the community’s ongoing needs. Detroit’s pilot is an excellent example of how cities can think about improving access from the ground up with the user’s perspective in mind and without a predetermined solution.

5. Mobility as a Service will definitely be one of 2019’s hottest topics — but it won’t end there

We’ve talked a lot here about Mobility as a Service and that this is where most of the companies like Uber or Lyft or Lime are ultimately headed: not a provider of one specific mode, but a mobility provider allowing multiple options for however you choose to get around. It’s likely part of the reason why Lyft bought Motivate and Uber bought Jump (both are bikesharing companies), and why we’ll continue to see more moves like that in the future.

So what will it mean to roll all these services into a single platform offering multiple modes of travel. Who would control the data? What would the role of the city be in helping to plan for travel demand? How would cities ensure that it improves access for everyone?

We had two representatives from the public side (Warren Logan from San Francisco and Alex Pazuchanics from Pittsburgh) discuss the topic with two reps from the private side (Lilly Shoup from Lyft and Matt Cole from Cubic.) And the back-and-forth that ensued (moderated by Cityfi’s Gabe Klein) was a terrific, open, and honest discussion that pulled no punches.

5. LADOT’s Mobility Data Specification is already shifting the conversation

There have been a lot of conversations over the past year about LA DOT’s Mobility Data Specification (MDS) and how cities can better use data to actively manage their operations. Starting with shared active transportation services operating in Los Angeles, Marcel Porras from LADOT shared more about their short- and long-term goals along with the topic of how cities manage the right-of-way today physically and how they will need to manage it in a digital future.

Apparent from the beginning of the conversation was significant interest from the participants to use MDS in their communities to accomplish similar goals. And, there was also a stated desire to work with Los Angeles to further co-create and build out MDS to help manage the other challenges they’re facing such as managing curb space, carsharing, ridesourcing and eventually automated vehicles.

One of the most poignant parts of the conversation was a deep dive into how MDS is being administered and governed today, how cities might work together to evolve MDS into a national standard, and how a governance structure might take shape that could foster its development long into the future. It was one of the best conversations we’ve had in the Collaborative this year and highlighted the growing need for cities to evolve their structures, capacities and capabilities as data management becomes paramount for mobility management.

6. We turned the tables and tossed the private companies into the Shark Tank

Cities get pitched all day long from private companies and providers. But it’s rarely in a forum where these maxed-out city staff can really engage in a thoughtful way and certainly not one where they can benefit from the expertise of their colleagues from other cities. So we tried to turn the tables a little bit and take a page from TV by creating the Smart Cities Shark Tank where private companies were given ten minutes to pitch a panel of reps from a range of cities about Mobility as a Service and curb space management solutions, and then take some tough questions from the panel as they tried to assess whether it would be a good fit for their cities. And then the panels huddled to evaluate the presentations and pick a “winner” with the best pitch for the cities.

Photos from the Smart Cities Shark Tank, including a picture of the location at Monday Night Garage on the BeltLine in West End.

The night was a lot of fun but it was also a useful exercise that forced the private companies to meet the cities on their terms and also allowed the cities to tap into the expertise of their colleagues from across the country—something they don’t typically get to do when one of these companies shows up in their office with a pitch.

Thanks to the International Parking & Mobility Institute for helping host the Shark Tank.

7. Year two is done, and we’re already looking ahead to year three

It’s hard to believe we’re already wrapping up the second yearlong cohort of the Collaborative, but we’re already looking ahead to another cohort of cities for year three in 2019.

We would never have been able to make the Collaborative happen without the hard work and leadership of Russ Brooks, who has been T4America’s Director of Smart Cities for the past three years (and has been part of T4America in some fashion for seven years in total.) He helped conceive of the program and pull together the initial group of cities that met on a fairly surreal day in Minneapolis after the 2016 presidential election, and he’s contributed his blood, sweat, and tears to build the relationships required to bring almost 150 participants from 27 different cities together throughout the first two years—and the private industry—to the table for such a productive and useful forum.

We’re especially grateful for the representatives from the 23 cities who came to one or more of these meetings this year and contributed their time and their wisdom and made the Collaborative, well, truly collaborative!

We’re actively looking for the next Director of Smart Cities to guide year three, and we’re hoping for someone with some experience on the ground within a city or agency to run the show. Read the job description here.

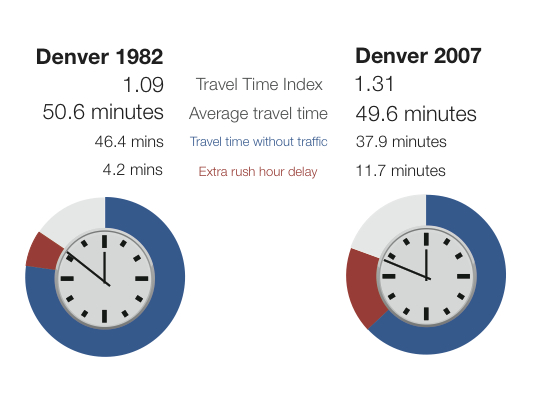

The second cohort of the Smart Cities Collaborative at our first 2018 meeting in Denver, Colorado.

Kicking off the first year of the Collaborative in Minneapolis on November 7, 2016.