The mayors of Monroe, Ruston, and Shreveport, Louisiana, have joined forces with the mayor of Vicksburg, Mississippi to fight for new Amtrak service through their communities. This move has placed these four local officials at the center of the national conversation about expanding long-distance passenger rail service.

The I-20 Corridor

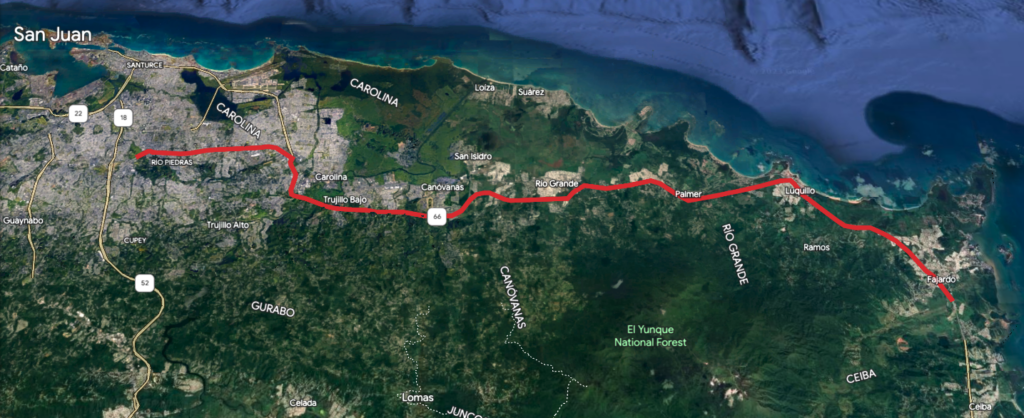

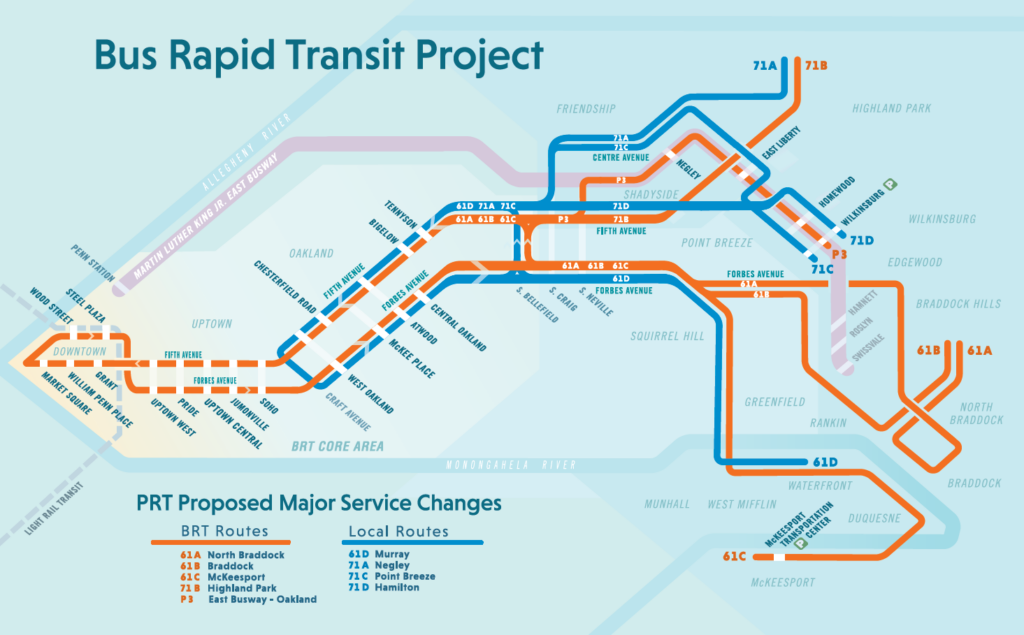

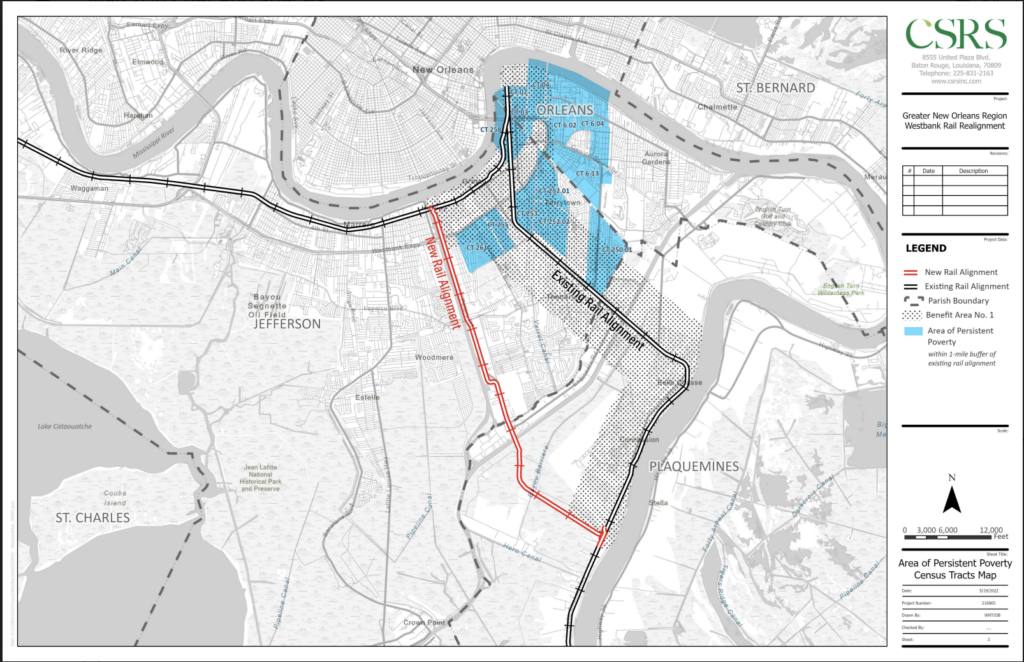

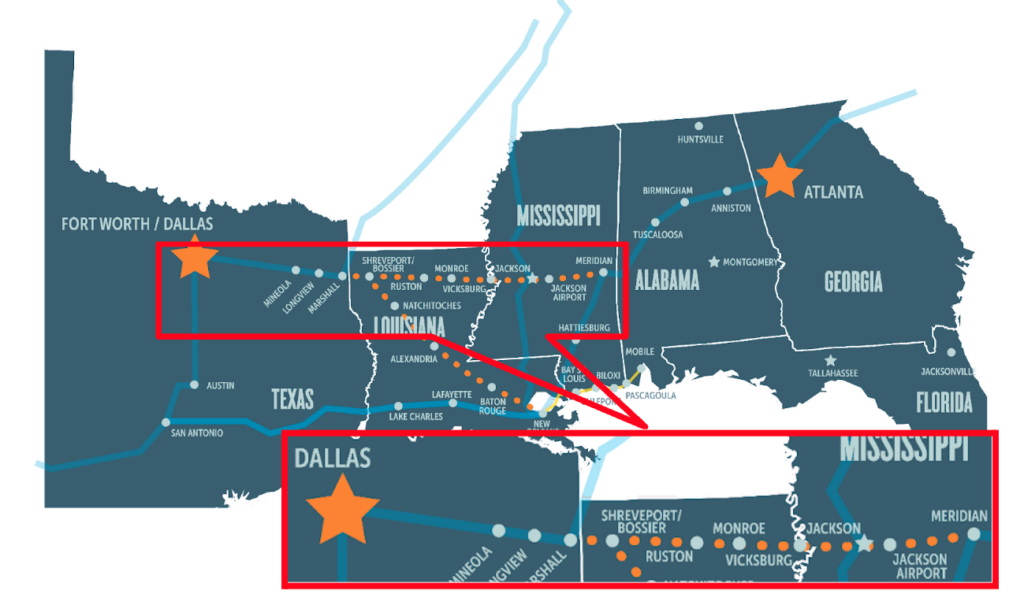

Mayor Friday Ellis of Monroe, Mayor Ronny Walker of Ruston, Mayor Tom Arcenaux of Shreveport, and Mayor George Flaggs Jr. of Vicksburg are working together to establish new passenger rail service along the freight rail corridor that runs along I-20 from Meridian, MS to Dallas/Fort Worth, TX (depicted below). The new service would be an expansion of Amtrak’s Crescent service through Meridian, allowing passengers along the I-20 Corridor to access Atlanta and other points north by rail.

“This route will be one more arrow in the economic quiver for small and midsize communities across the Deep South,” said Beth Osborne, Director of Transportation for America, in our statement in April.

On April 21, in partnership with these mayors, Amtrak and the Southern Rail Commission (SRC) submitted an application for the Federal-State Partnership for Intercity Passenger Rail (Fed-State) program to study the corridor and plan for future service. This application is a huge step forward and has led to much fanfare in the cities that stand to benefit, but service isn’t guaranteed yet. First, the FRA needs to decide whether to grant the award.

So the four mayors, joined by the SRC and CPKC (the railroad set to host this new service) Assistant Vice President of US Government Affairs Arielle Giordano, traveled to Capitol Hill to meet with members of Congress and build a coalition of support around their application.

And we had the pleasure of escorting them around.

Local leaders have national impact

Mayors Ellis, Walker, Arceneaux, and Flaggs Jr. joined us in Washington, DC during the week of April 17-20 to meet with their senators and representatives as well as officials from Amtrak and the Federal Railroad Administration to discuss the I-20 passenger rail project. They outlined the details of the project, what federal funding they need, and why the project is important to their cities.

To make their case, the mayors focused on how the new passenger rail service will fit into their communities. They each told a story about who will ride the train, for what reason, and to where. Each community’s story was different, and each contributed something different to the group’s collective argument.

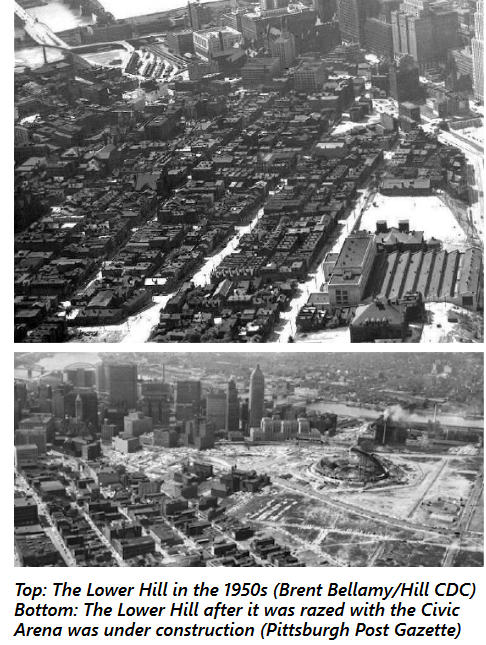

Mayor Friday Ellis described how the new station would be a core piece of Monroe’s plan to revitalize its downtown. So when the train stops in Monroe, people will have dozens of options for restaurants, shops, offices, and other amenities to choose from within walking distance. This will allow families with young children, students at the University of Louisiana Monroe, and every Monroyan to better access downtown and West Monroe (across the Ouachita River). This is why Mayor Ellis often says that the people of Monroe are more excited about this project than any other.

Mayor Ronny Walker is even further along. Much of Ruston’s downtown revitalization is well underway, and the station will fit right into it. Ruston has also invested in automated vehicle transit systems to connect the station to the nearby Louisiana Tech University (which along with nearby Grambling State University is a strong supporter of the project). The Ruston station will also be directly adjacent to the Louisiana Center for the Blind and therefore serve a community that relies heavily on rail and other transit to get around.

Mayor Arcenaux in Shreveport was inaugurated in January, so he is brand new to the role. But he has already developed a strong relationship with SporTran, the city’s transit agency, which is now working on plans to connect people from all over Shreveport and neighboring Bossier City to the new station. This will improve access to goods and services for the whole community, especially for residents that do not own cars.

Mayor George Flaggs Jr., an advocate of historic preservation, has latched onto the passenger rail plan as an opportunity to efficiently bring tourists into Vicksburg’s historic downtown and its Civil War battlefield. He has been able to pitch the project as a way to meet the immense tourism demand by bringing train-loads of riders straight into downtown – taking advantage of this major advantage of passenger rail over air or road travel. This will generate economic growth in downtown Vicksburg that will benefit residents for years to come.

By telling these stories, the mayors were able to make considerable progress in the push for the I-20 Corridor—perhaps more progress than anyone else in the 30-year long effort to bring this service to the Deep South. For example, one of the most impactful visits was with two representatives from Texas whose districts would host part of the new service. None of our group was from Texas, but they made such a persuasive presentation that the two representatives decided to submit letters of support to FRA for the project. Members of Congress rarely make such commitments to non-constituents.

The passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) in 2021 ushered in a once-in-a-generation opportunity to expand passenger rail. But taking advantage of this $100+ billion in federal funding will require the rapid coalescence of federal, state, and local governments. Mayors Ellis, Walker, Arceneaux, and Flaggs Jr. are demonstrating that local leaders are often best suited to make that push. Our job is to help them.

See more of the mayors’ visit by clicking through the gallery below.