Reconnecting the Hill District to downtown Pittsburgh

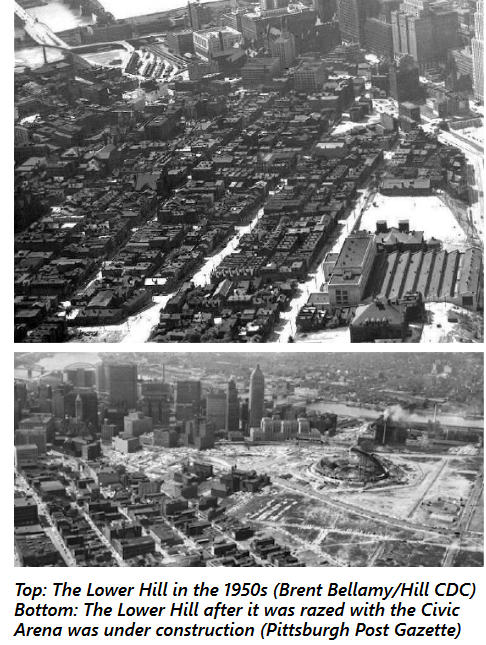

In its heyday, the historic Hill District neighborhood was bursting with life. It was full of opportunities and culture; residents treasured it. After slowly cultivating a unique identity through generations and incremental layers of growth, it was nearly destroyed in just a few short years through the building of I-579 and the Civic Arena. Now, 60 years later, some connections are being restored.

A cultural district cut off from downtown

The Hill District of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, located just to the east of the core of downtown Pittsburgh began as a community of freed Black men and women early in the 20th century. As the city’s first Black district, it became a “cultural icon,” known for its jazz scene, radio station, and weekly newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier. Following World War II, the Hill’s aging housing infrastructure, in conjunction with “crime and disease” (how the city defined it) became the basis to justify drastic urban renewal. Over 95 acres were condemned by the city. Developers came in and began taking houses by eminent domain to “revitalize” the neighborhood. This was the beginning of a swift downfall for the Hill District.

The plan for I-579, which today cuts directly across Pittsburgh and crosses the Allegheny River to connect with I-279, was conceived almost a decade before any work began. In 1949-1950, there were ongoing conversations about building a highway from Liberty Bridge to Grant Street, at the the end of Bigelow Boulevard. This would cut across the Golden Triangle, enabling a quicker, less congested commute across the city. After a few years of back-and-forth over route and cost, the city and county finally agreed to split the cost of an “82-foot-wide, six-lane expressway.” The City Council passed an ordinance establishing the right-of-way for the partially elevated, partially below grade project, cutting through the Hill District. The repercussions of the expressway on the Hill District were either never considered or blatantly ignored.

In 1957, much to the City Planning Commission’s displeasure, the state announced that Crosstown Boulevard would be part of the newly created national Interstate System and moved forward with a larger, wider highway than they had originally approved, now backed by federal dollars.

The expressway, built in two sections, was completed by 1964. Simultaneously (1961) a new arena (home to the NHL’s Pittsburgh Penguins) and adjacent parking were constructed in the Hill District (South Side). All told, the destruction required to build I-579 and the greater urban renewal efforts resulted in the displacement of over 8,000 predominantly Black residents and 400 locally owned businesses. In addition, almost overnight, the Hill District was cut off from downtown right next door.

“The massive highway constructed at the base of the arena severed the residents of the Middle and Upper Hill from downtown and any kind of continuity with civic life,” according to this piece in Belt Magazine. For residents of this low-income neighborhood, in a (previously) well-connected central location, walking to work, or walking to access essential needs and services, was no longer an option. By the mid-1980s, the Hill District had “deteriorated into a shell of its former self.”

A path forward: The “Cap” Connector

Before and after cap construction. Photos from HDR, Inc.

Today, there is a new cap over a portion of I-579, creating a limited new connection between the Hill and Downtown, restoring access to employment, education, and services—now known as Frankie Pace Park. The cap and park were built (2019-2021) in the open air space above a portion of the below grade I-579 just to the west of the old Civic Arena site The project was initiated by the Penguins’ move into a new arena a few blocks away in 2010, after which the owner of the Penguins demolished the arena and replaced it with 28 acres of parking. The Urban Redevelopment Authority threatened to take one-fifth of the parking revenue unless 6.45 acres were redeveloped by 2020. The Penguin’s owner acquiesced. Approximately half of this land would become Frankie Pace Park, the remainder would be used for mixed-use development.

The space includes bicycle, pedestrian, and ADA access through and around the three acres of land, as well as rain gardens, performance areas, recreation space, and other public amenities. Improved sidewalks, lighting, and signage were included in the project for improved safety and use at all times of the day, as well as curb-cut ramps and enhanced crosswalks at intersections leading into the space.

This project was funded by a combination of federal and state sources including: USDOT through a TIGER (round 8) grant, PA Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program, PA Department of Transportation (Multimodal PennDOT), PA Commonwealth Financing Authority (Multimodal DCED), and PA Department of Conservation & Natural Resources (DCNR Keystone Recreation, Park and Conservation Fund). Several local agencies and foundations also provided funding.1

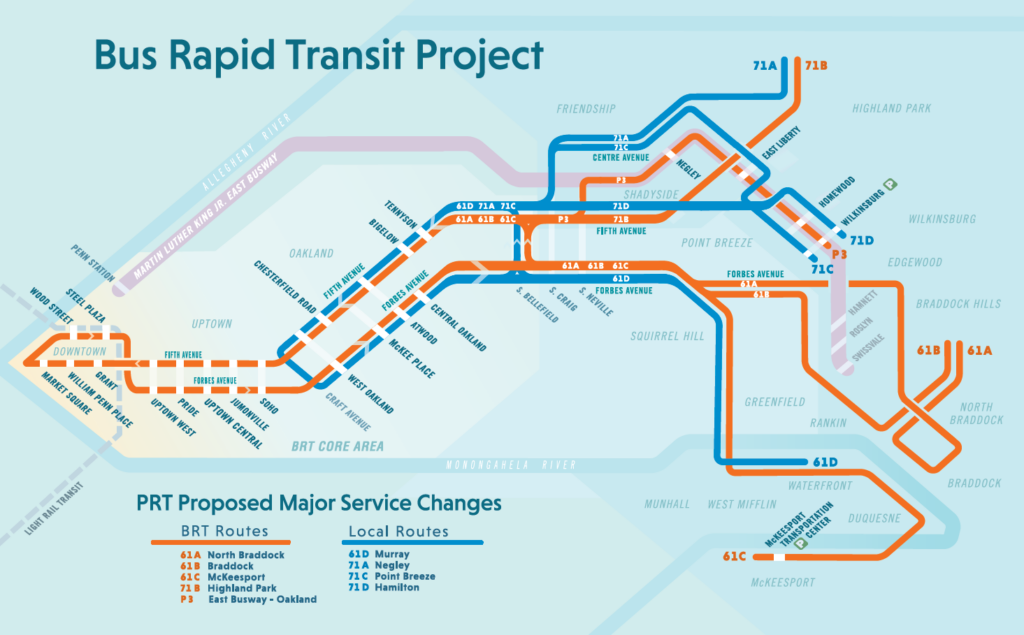

An additional aspect of this project was its location near an existing subway station, a new bus stop, and a (then) proposed bus rapid transit system (BRT). In March 2023, the Pittsburgh Regional Transit announced approval for the first phase of this project, connecting Downtown, Uptown, and Oakland. Five new stations will be added downtown, including one at Steel Plaza station, made more accessible to Hill District residents by the new park. The electric buses will move along dedicated lanes to ease congestion and improve commuter efficiency.

Still more work to do

In August of 2022, Pittsburgh received a federal RAISE grant to further address the harms caused by I-579. Projects funded by the RAISE grant, including curb extensions, new sidewalks, and intersection improvements, will help make the Hill District a safer place to walk for those who are still left in the Hill District.

From the looks of the new park, it can be deemed a success. However, this new park and new connections do not address the issues of past and current displacement and harm that was done to this community over decades, and which continues today.

Lessons for budding community connectors

Transportation and land use are inherently intertwined. As we advocate for development, and redevelopment, and fight to reconnect communities, we must always consider how one variable impacts the others—at the micro and macro levels. The building of I-579 had tremendous repercussions on housing and access (to employment, healthy food, community services, etc). That transportation decision to cut an entire neighborhood off from opportunity to serve thru-commuters had cascading effects on land use decisions across the region. And then 60 years later, the land use decision to create the cap created valuable new transportation connections between the Hill District and downtown. These decisions are inexorably connected.

Projects like these can require significant cooperation and a diverse range of funding sources. Building an interstate is relatively simple—the federal government provides 90 percent of the funding for the project. But Frankie Pace Park, which took nearly a decade to develop, required the cooperation of multiple local, regional, and state agencies, leverage placed on private landowners, and funding from a wide range of sources. Engaging a broad range of stakeholders is required for these complex projects, so get everyone to the table.

The cap is a band-aid on a historical wound. The cap and new park, although successfully built, doesn’t do enough to right historical wrongs and steer the benefits to come from the connection to those who were displaced. The best intentions are no replacement for listening to, including, and prioritizing the voices of those who lost their neighborhood in the first place. Successful reconnecting communities projects should reflect the needs and goals of the existing community, and that can only happen by engaging everyone in the process and empowering them to shape the final product.

Community Connectors: tools for advocates

You may be fighting against a freeway expansion. You may be trying to advance a Reconnecting Communities project to remove an old highway. You might be just trying to make wide, dangerous arterial roads a little safer for people to cross. This Community Connectors portal explains common terms, decodes the processes, clarifies the important actors, and inspires with helpful real-world stories.

You may be fighting against a freeway expansion. You may be trying to advance a Reconnecting Communities project to remove an old highway. You might be just trying to make wide, dangerous arterial roads a little safer for people to cross. This Community Connectors portal explains common terms, decodes the processes, clarifies the important actors, and inspires with helpful real-world stories.