With scores of competitive, surface transportation grant programs to administer, USDOT faces a heavy lift to get these programs off the ground, on top of administering the legacy programs that already existed. How should prospective grant applicants start preparing for success?

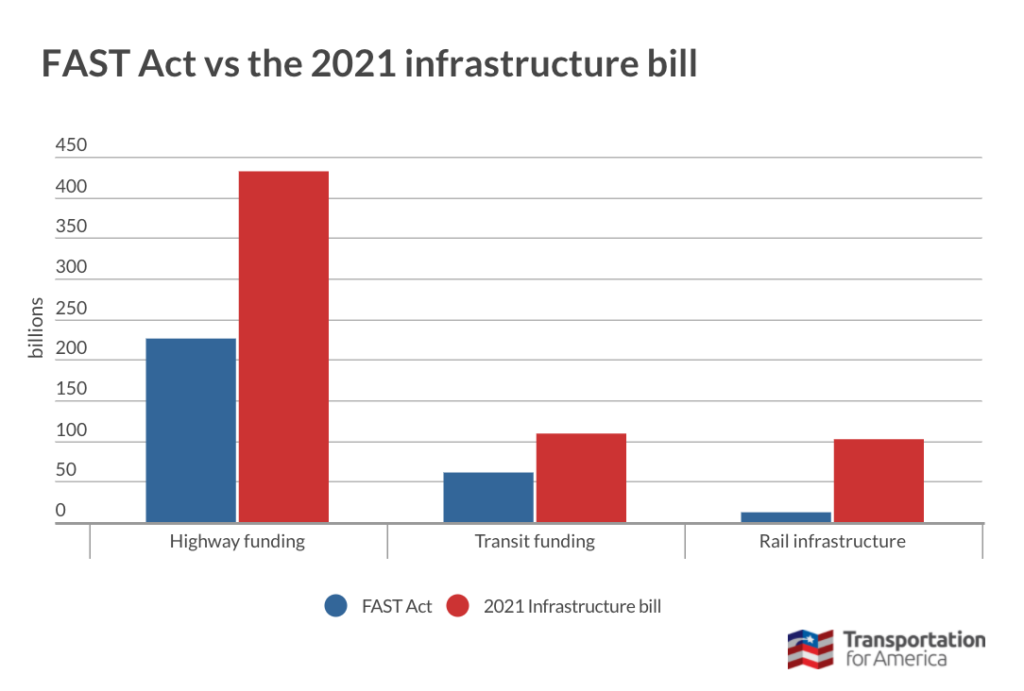

This post is part of T4America’s suite of materials explaining the 2021 $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which governs all federal transportation policy and funding through 2026. What do you need to know about the new infrastructure law? We know that federal transportation policy can be intimidating and confusing. Our hub for the new law will walk you through it, from the basics all the way to more complex details.

The USDOT will have to find ways to administer and harmonize nearly five dozen programs with other Biden administration goals, like the Justice40 initiative that emphasizes equitable distribution of resources, especially towards historically marginalized communities. They’ve got a lot of work to do. But communities don’t need to wait on USDOT to begin preparing their projects that emphasize the state of repair of their transportation system, advance safety for all users, and improve mobility and access for all people.

Here are three pivotal strategies that communities can use to better position themselves to win competitive grants.

1) Match project objectives to the program criteria

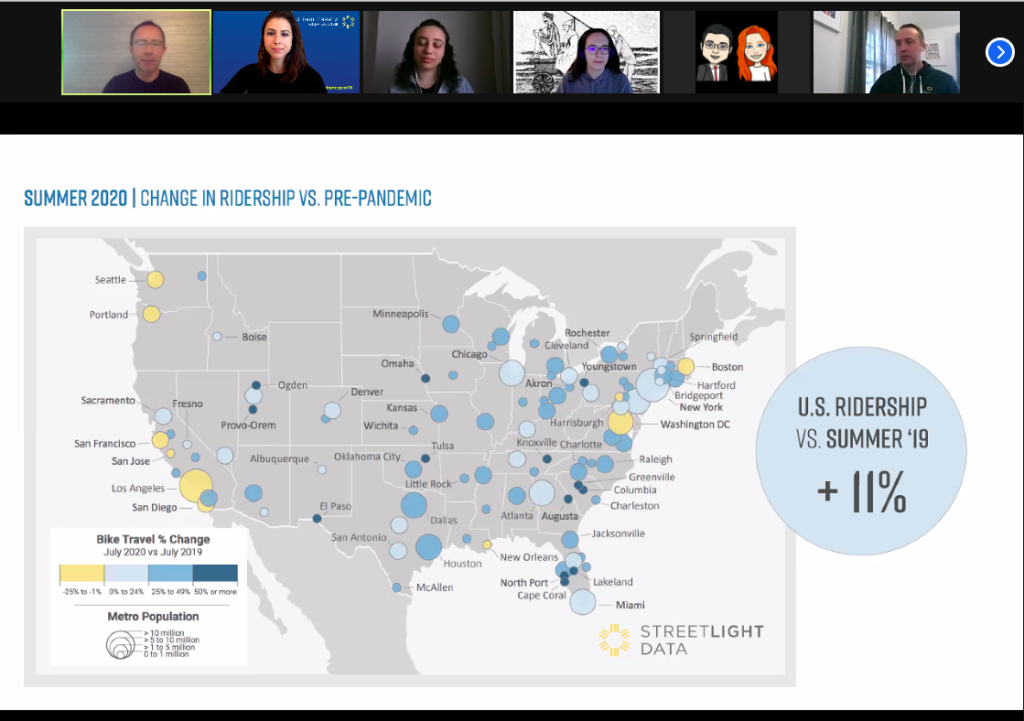

The most successful projects clearly define the problem or need of your community, and tailor the project to clearly address these needs—and those needs match the criteria that USDOT has laid out for evaluating projects. This means collecting and utilizing data, observations, and community feedback that affirm the problem or need.

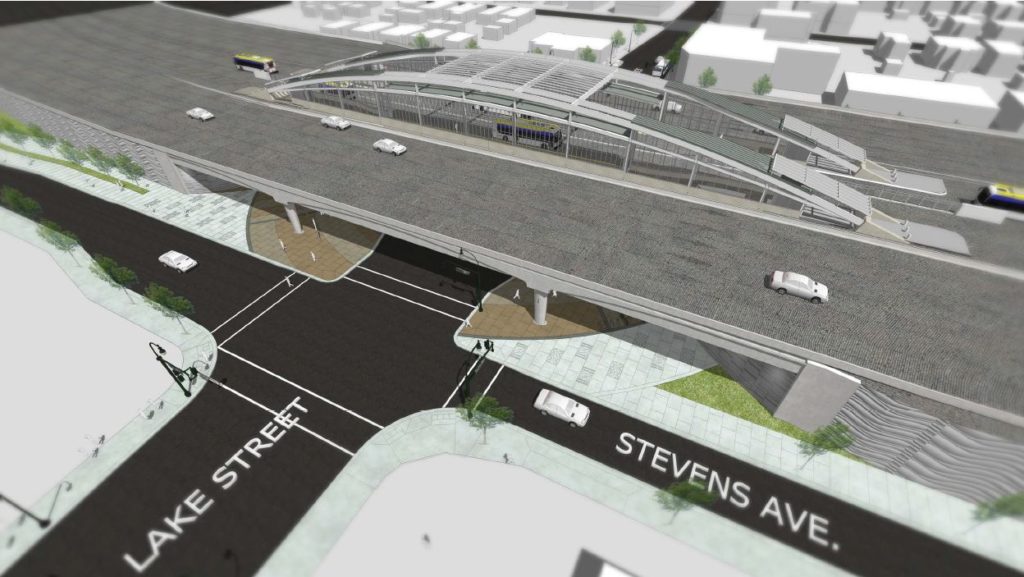

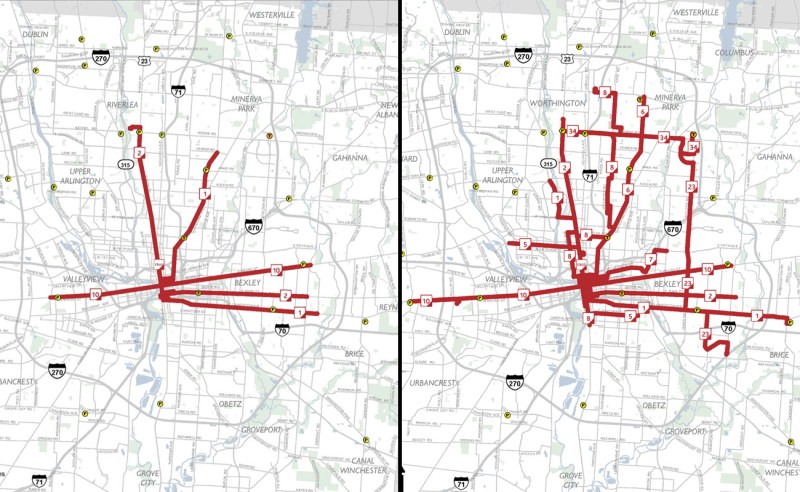

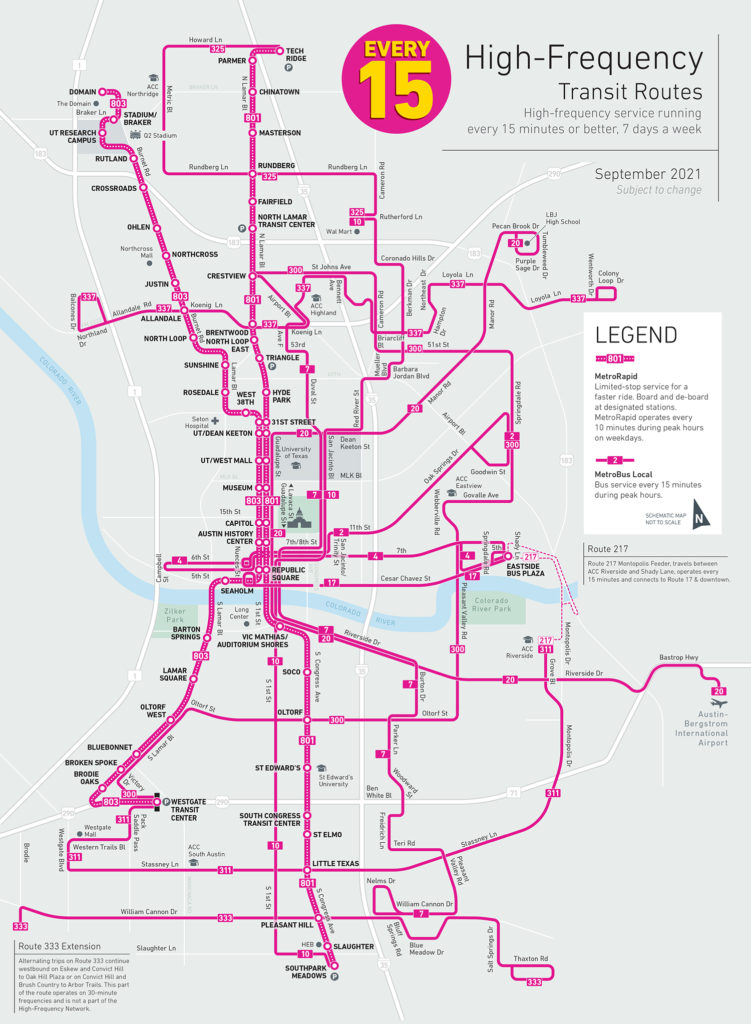

It also means putting the project in context. Remember those reviewing your application may not be familiar with your project or your challenges and may never have been to your community at all. So start your application by clearly stating what the project is, why it is needed in the community, what will be accomplished by building it, and other efforts in the area (past and current) that will support those results. It is also helpful to include maps, pictures, and sketches to help those reviewing your application fully understand what is at stake and what could be accomplished.

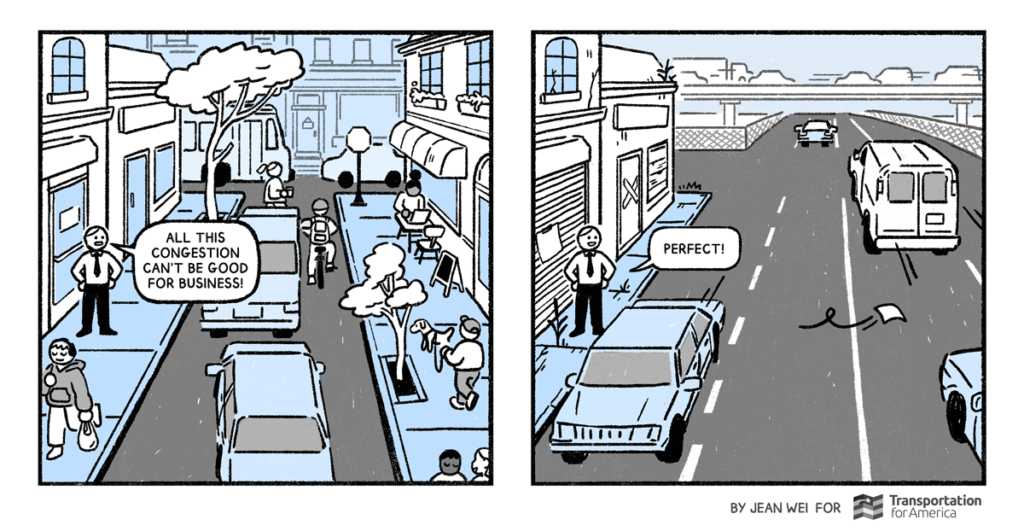

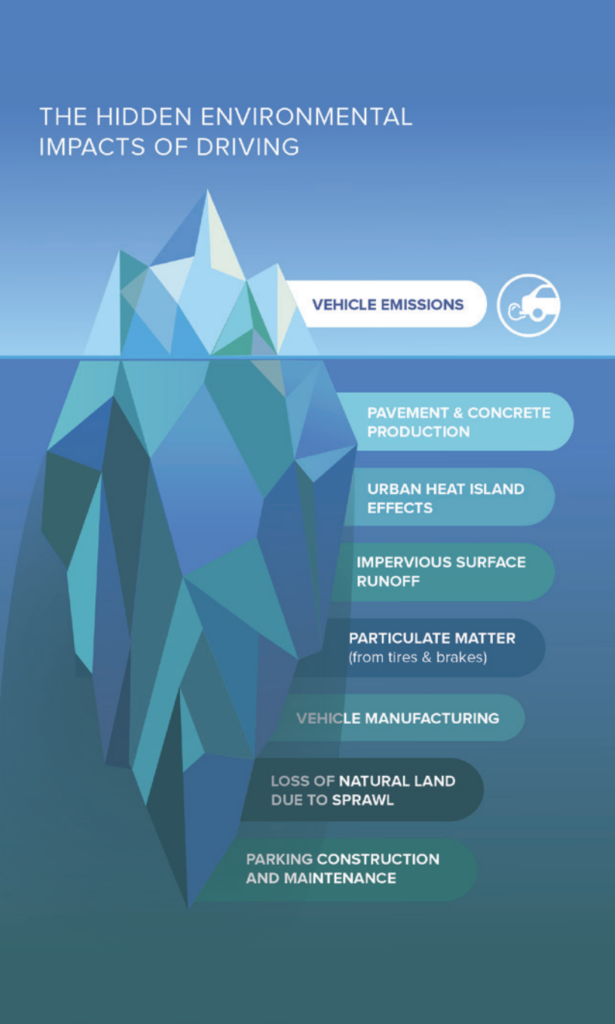

For example, depending on the context of the grant, USDOT looks favorably upon projects that are well-integrated into the development of their adjacent built environment and region, and that have broad support from everyone involved or affected. While transportation projects can have specific goals like cutting down on traffic or creating economic development, they should not do these at the expense of other goals like equity, housing affordability, or environmental health. USDOT recognizes this and rewards projects that form diverse coalitions, have buy-in from local businesses, and best meet the broader needs of the surrounding community.

Projects will be filtered for eligibility but evaluated first and foremost on how well they address the criteria included in the notice of funding opportunity. Everything else is secondary. Your project does not need to knock it out of the park on all of the criteria (rarely does any project do that), but it should produce impressive results in two or three areas.

2) Build a strong, broad coalition of support

Projects with a broad base of supporters will always do better. This means support from the community, civic leaders and local elected leaders. It also helps to have support from your state, especially if you need your state department of transportation to manage the money or help with the project. But USDOT will understand if you are dealing with a state that does not share your (and USDOT’s) priorities. If that is the case, state it outright.

When building a coalition for a project, consider who else would care about a potential project? Who else is a logical partner and stakeholder that you could collaborate with? Perhaps a neighboring community is also pursuing a similar priority, presenting a chance to pool resources together. Explore partnerships with the private sector. Advocacy to state legislatures to set aside funding to support state and local matches to grant programs, like what Colorado is doing, can go a long way in making grant applications more competitive. And even better is to build or develop projects from the beginning with partners and stakeholders who will be automatic champions as that project moves forward, rather than trying to gather support for a completed project idea.

A broad range of supporters can help you put together a local match, which most competitive grant programs still require. State and local project sponsors must bring some amount of non-federal funding to match the federal dollars. Any funding that does not originate with the federal government will do, including local, state, philanthropic, business and even some in-kind contributions. A broad number of contributors is often more impressive than a larger single source of funding. This is important because projects often run into trouble along the way. Maybe bids come back high or construction finds an unexpected utility or artifact. When such problems occur, projects are more likely to proceed and be successful with a broad range of support.(It’s nearly a decade old, but our primer on local revenue best practices is still a good starting point to learn about the available options.)

Finally, support from your congressional delegation is good too. It won’t help if your project doesn’t match the program criteria, but USDOT might use this support as a tie breaker. If there are a few equally good projects, it just makes sense for USDOT to choose the one that has support from the Congressional delegation. Letters are a good starting point, but phone calls and meetings with USDOT are better.

3) Know the funding program parameters

Choosing and applying to the right competitive grant program is necessary for most effectively coordinating the above strategies. If you would like to know the breadth of options available, check out our funding briefs. You can view all the various programs by the projects they can fund and for which jurisdictional level. Note: many grants have wide flexibility that may not be immediately obvious. We did our best in these funding briefs to describe these flexibilities, so read closely.

Once an applicant selects a program, applicants must identify what USDOT requires for that funding. The Notice of Funding Opportunities (NOFO) for each program explicitly states the requirements (such as the 2022 RAISE grants NOFO that was released on January 28th). Past NOFOs and grant applications—even from other applicants!—available in the public record, are a useful resource for understanding what successful applications look like. Applicants who are willing to put in more time can dig into the US Code (23 or 49 USC) or the Code of Federal Regulations (23 or 49 CFR).

Applicants will also need to set up the necessary administrative steps. For instance, they will need to know or request a Unique Entity Identifier through SAM.gov. If your organization has been using a DUNS number, a unique identifier has already been assigned since the federal government is migrating away from DUNS by April 4, 2022. These steps are more numerous than we can easily include here, but we can direct you to some resources that can help: 1) The USDOT maintains a website on how to do business with the FHWA, which contains a specific page on FHWA terms and conditions, 2) FTA has its own website outlining the The Transit Award Management System (TrAMS), its hub for federal transit grants, and 3) the General Services Administration maintains a site for live grant opportunity listings.

Read and pay close attention to who is eligible to apply, what projects are eligible for funding, as well as when and how to apply. And get to work on all of these requirements early. Get your Unique Entity Identifier as soon as you can, as this will take weeks if you don’t already have one. In fact, you do not have to wait to apply for a grant to set this up. Also, Grants.gov requires you to set up an account, and it can get overloaded by very popular programs close to the deadline. Don’t risk it! Do everything you can in advance. Apply a week early because you will not get more time if the system goes down at the last minute.

Still unsure on program parameters or if your project is eligible? Each NOFO lists a webinar to get an overview of the funding opportunity, ask questions, and learn the process to follow up with additional questions. You can also contact your FHWA Division HQ or Regional FTA HQ and ask questions of them over email or phone. In addition, T4A members gain access to our staff and our knowledge of federal programs.

Want access to in-depth analysis of what your community needs to do to tap into federal funding? Consider joining as a T4A Member.