Advancing equitable transit-oriented development requires all hands at the community level, but leadership at the state and federal level can also help propel change.

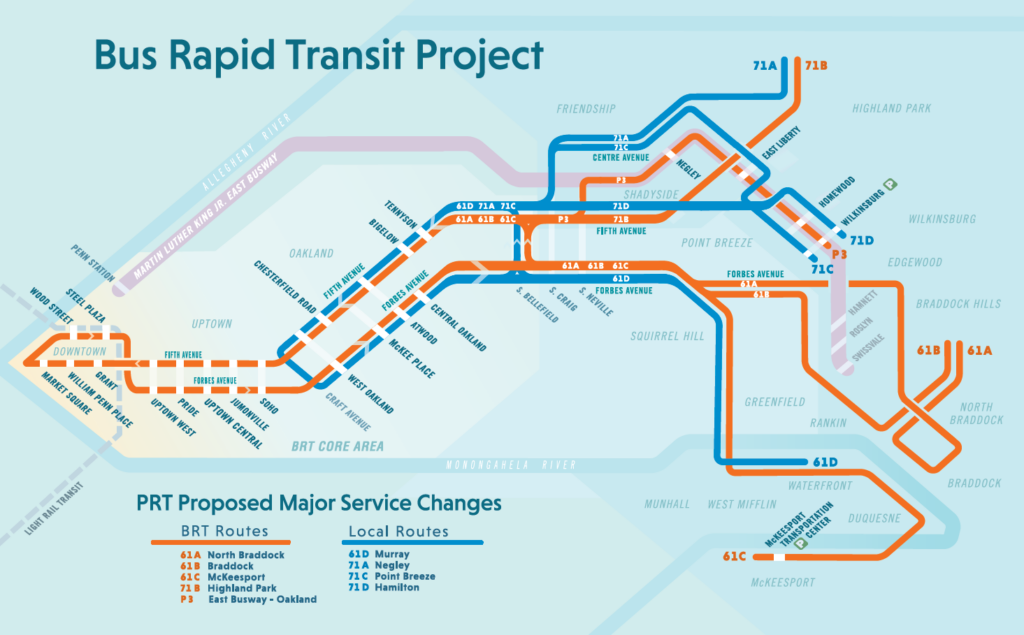

Public transportation and housing work in tandem. People want to live in walkable areas that are close to frequent transit stations to move around quickly. Equitable transit-oriented development (ETOD) helps meet this desire by maximizing the amount of residential, business and leisure spaces within walking distance of public transportation.

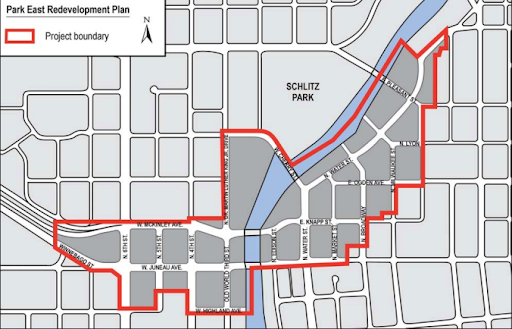

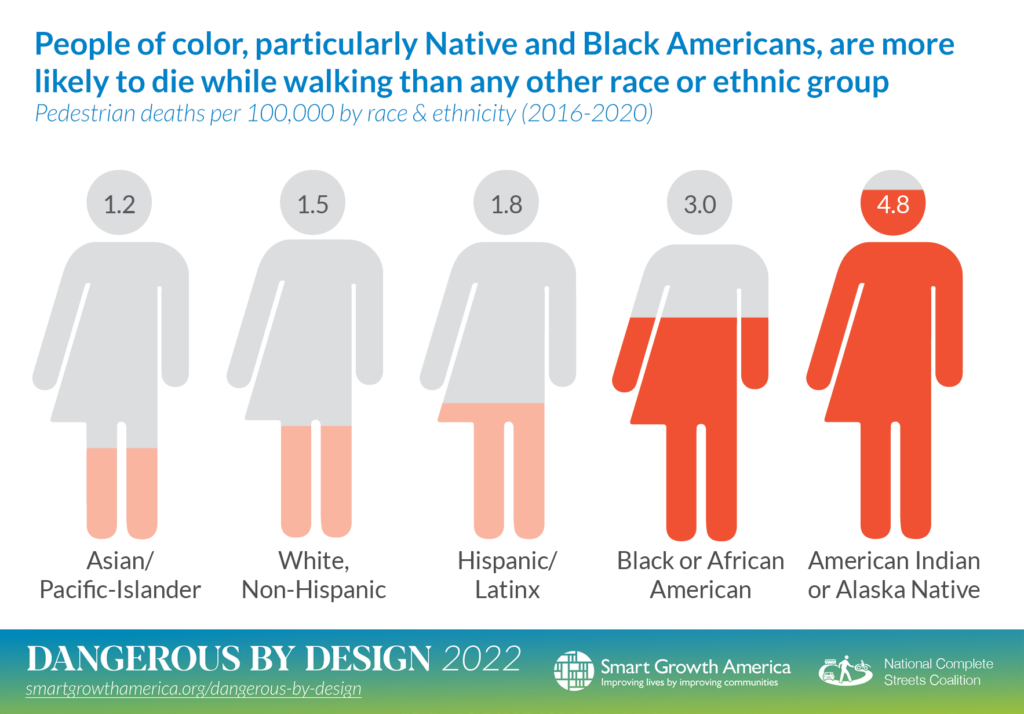

Locating public transit near everyday destinations promotes ridership and makes it easier for people to travel without needing a private vehicle. It’s a vital component to establishing well-connected communities and promoting economic growth. However, it’s difficult to build any form of transit within one mile of residential spaces.

On June 26th, 2024 the Future of Transportation Caucus hosted a congressional briefing focused on equitable transit-oriented development. Here are a few of the barriers to ETOD that came up during the briefing.

Local legislation can restrict development

Principal Research Associate from the Urban Institute, Yonah Freemark explained during the briefing that many localities have land use policies that restrict dense and mixed use buildings near transit.

Additionally, zoning laws in many cities have been stagnant in updating their codes. Planning Manager for the City of Columbus, Alex Saursmith, highlighted this point with his own city, where the zoning code has not been updated in 70 years. Currently, only 6,000 housing units can be constructed every 10 years, despite Columbus being one of the fastest growing cities in the country.

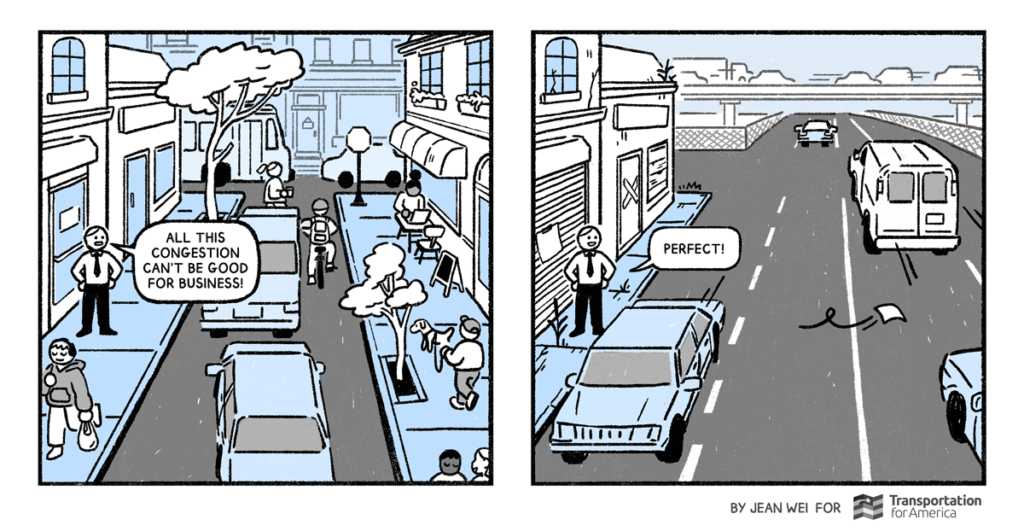

ETOD is also more financially effective than supporting continued road-building by prioritizing development density. It better maintains and maximizes the benefits of existing infrastructure. As LOCUS Chair Alecia Hill explained, state legislators should have an economic financial incentive to promote equitable transit-oriented development. When a lack of housing supply coupled with a lack of transportation options drives up household costs, residents are the ones who pay the price.

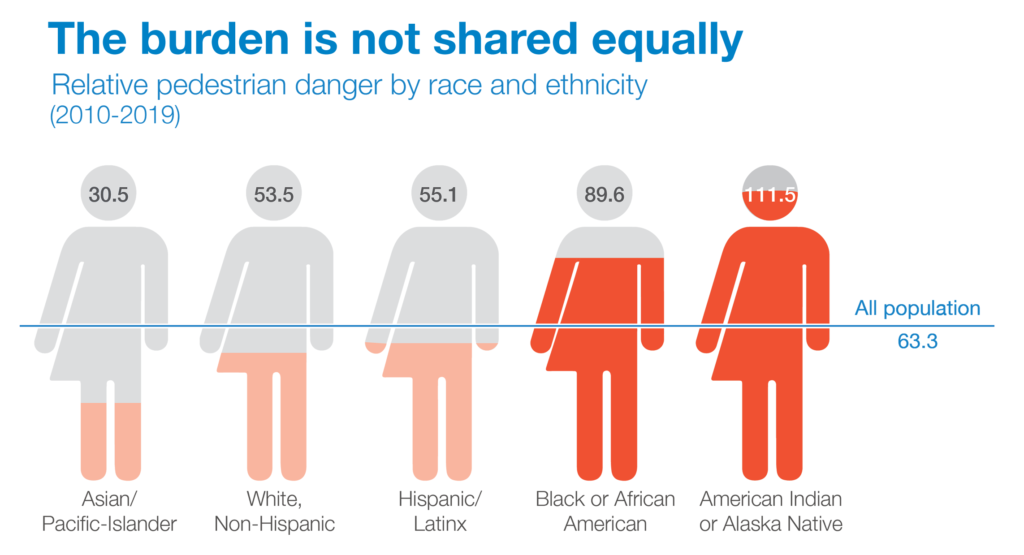

Transportation costs are the second largest expense category, behind housing, for most households. When households are already severely economically constrained, the costs of housing and transportation can be particularly difficult to meet. Renters that are cost-burdened or severely cost-burdened can spend greater than 30 or 50 percent, respectively, of their gross income on housing costs, according to the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. The Bureau of Transportation Statistics found that households with income lower than $25,000 who own at least one vehicle spent 38 percent of their after-tax income on transportation in 2022.

Community voices are key

Community input is a foundational factor to rally support for more housing and transit. It’s important for citizens to have an opportunity to provide input early and see how their concerns will be addressed.

Sometimes, residents oppose new housing development for a variety of reasons, ranging from a fear of losing a community’s identity to a fear of increased traffic or reduced property values. Practitioners and legislators should listen and respond to these concerns. For example, they could point to research like this study from Livable Cities Lab which showed that some property values increased when more housing was introduced. In addition, legislators working to adopt new zoning regulations would be wise to find their local allies and enlist their help in developing community support. Explaining how new housing development relates to the community’s values and goals can further strengthen the case for change.

As Saursmith explained during the briefing, areas that have seen high population growth are a major driving force to zoning reform, especially when those areas are economically disadvantaged. These places are in desperate need of more housing, especially mixed-use residentials within walking distance to transit. He notes that with noticeable population growth, innate political pressure grows to update local amendments that have become obsolete. Generally, political pressure on leaders is the start to policy-making change.

Labor perspectives are also vital to promoting ETOD, especially within the realm of unions. Executive Director of Good Jobs First, Greg LeRoy, explained that some unions have begun to embrace urban density, arguing that promoting density is not only beneficial for the environment, public health, and economic growth, but also innately pro-union and pro-jobs.

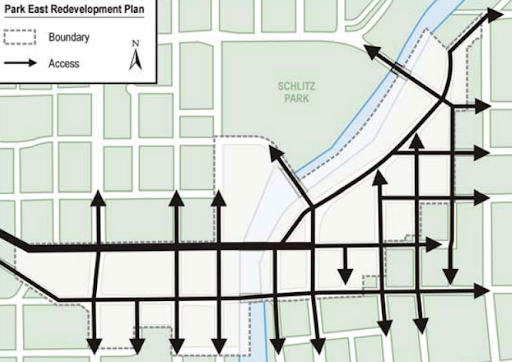

More equitable, better connected communities

Updating zoning laws requires having local city council members and state leaders actively and loudly call for reform. Calling local representatives and campaigning for leadership that will advocate for updated zoning laws is part of the solution to allow for more housing. The other side of the issue to address focuses on the grassroots level. Tackling discourse in online spaces, attending city council meetings in promotion of more housing near transit, or canvassing on referendums are all opportunities to promote ETOD.

Even federal leaders like members in the Future of Transportation Caucus make waves to address housing and transit, helping to propel the conversation forward. In 2020, Representative Jesús Chuy García introduced a bill to promote housing near transit and establish an office under DOT specifically for ETOD. These avenues all provide a chance to showcase the numerous economic, public health, and environmental benefits of constructing housing near transit.