Our failing federal transportation program is supposed to be completely paid for with gas taxes, but since 2008, Congress has taken an additional $275 billion from taxpayers (on top of all gas taxes) to cover the difference between gas taxes and their spending. And it’s only getting worse.

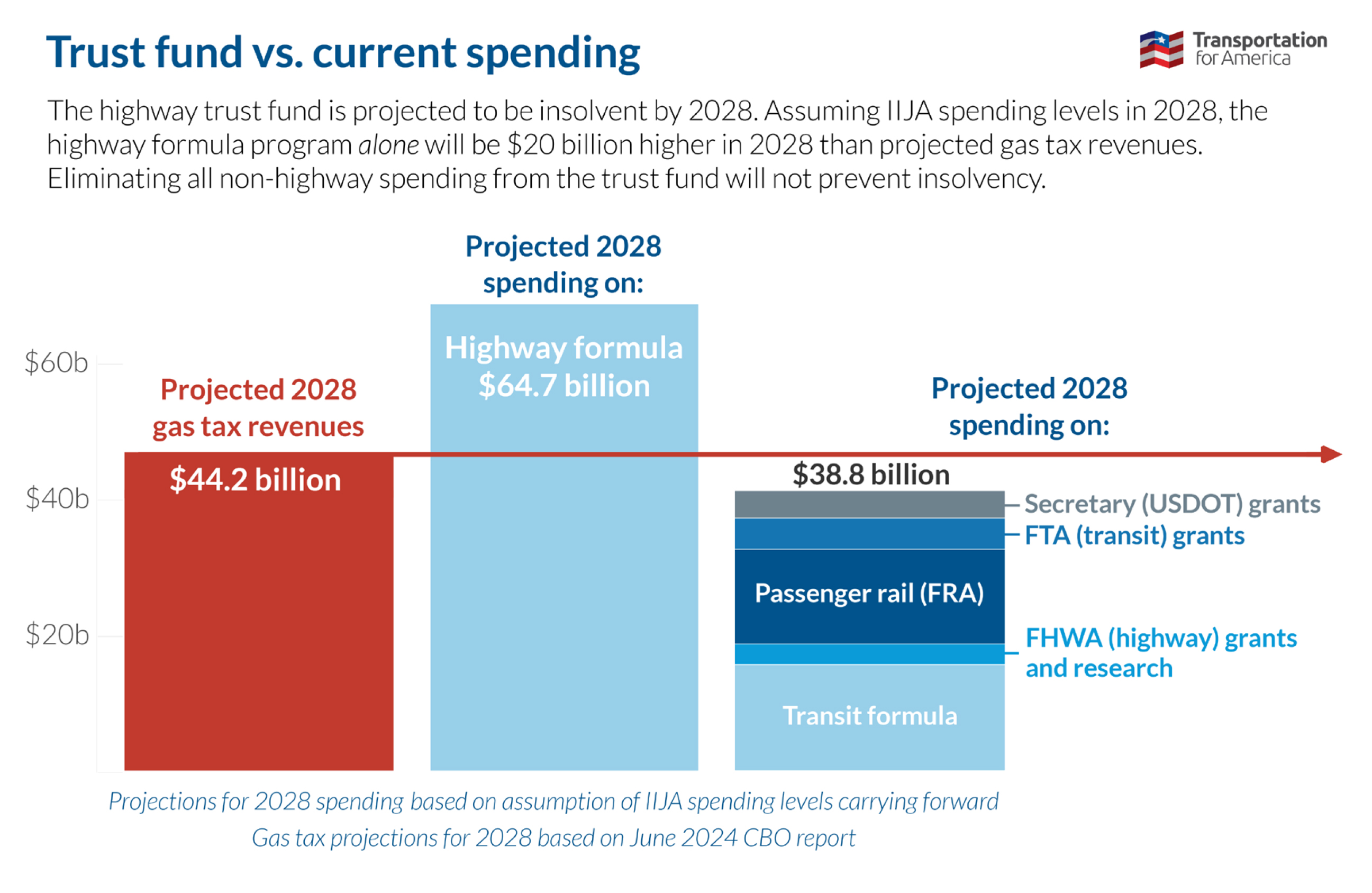

You may have heard about the looming “fiscal cliff” for the country’s federal transportation trust fund in 2028. We can climb a cliff—but this is more like a chasm: The Congressional Budget Office projects that, by 2027, the gap between trust fund revenues and spending will reach $40 billion annually, resulting in an overall deficit of more than $240 billion by 2033. To put that $40 billion gap in perspective, the entire federal-aid transportation program spends about $77 billion per year.

This deficit is happening for one basic reason: Congress keeps spending far more than the gas tax brings in.

But first, how did we get here?

There’s a much longer version of this story, but let’s start with the shorter one.

Every time you buy gas, 18.4¢ per gallon (and 23.4¢ for diesel), as a “user” of the transportation system, you pay into a protected federal trust fund for transportation called the Highway Trust Fund.1 (Despite its name, the fund also has a Mass Transit Account because transit benefits drivers too by taking all of those potential drivers off the road.) There are other small fees on tires and related things, but 90 percent of the trust fund’s money must come from fees charged to the users of the system.2

Here’s how trust funds work: Users pay fees directly into a protected trust fund over a long period of time, and then those funds must be spent to benefit those users. The users (those who buy gasoline) pay directly for the system (roads and transit systems.) This allows the transportation program to be protected from the typical annual appropriations fights over a program’s funding levels. Gas taxes roll into the trust fund and then get distributed back to states via a multi-year authorizing law, usually five years for transportation. For example, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 allocated those anticipated user fees for five years.

Since its inception, the bedrock principle of our federal transportation program has been that the user (through the trust fund) covers 100% of the cost of the federal transportation program for highways and transit. And, other than a rocky start in the 1950s and 60s, users did cover that full cost for years. Until 2008.

The trust fund is not “threatened”—it died in 2008

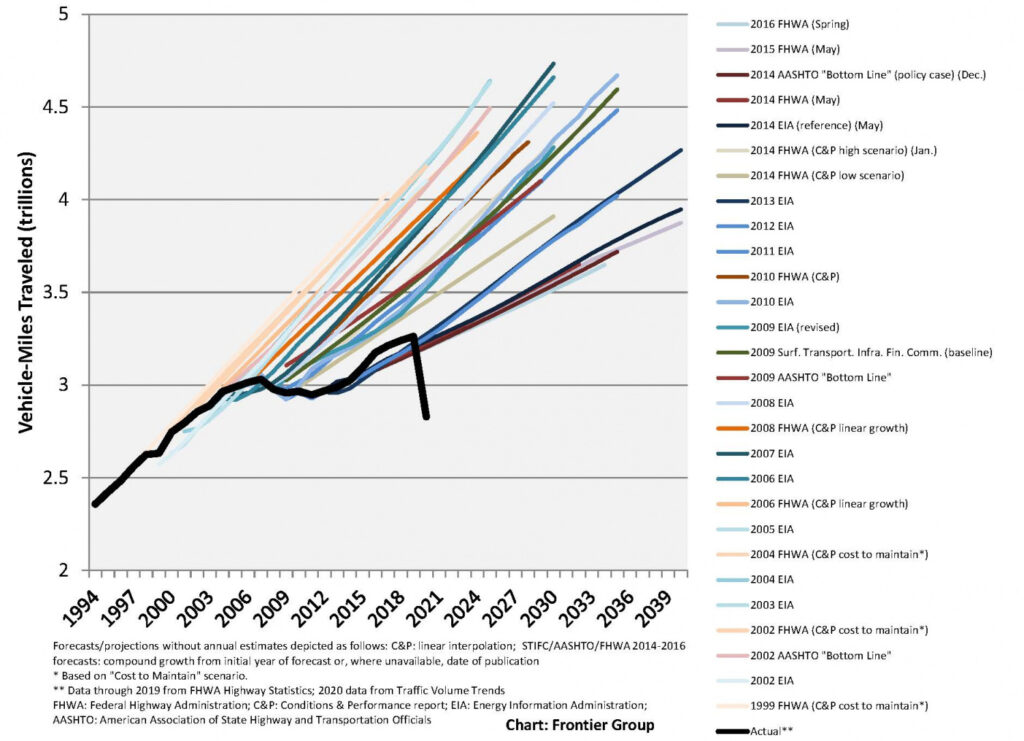

In 2008, after rosy projections of growing gas tax revenue by Congress in the 2005 surface transportation reauthorization law failed to materialize as growth in driving slowed, Congress was forced to make an emergency bailout of the trust fund, transferring $8 billion in general funds into it to keep it from becoming insolvent. 3 But this September 2008 bailout just turned out to be just the first of many. Flash forward to 2025, and Congress has now made a total of nine transfers totaling $275 billion—taken from all taxpayers, regardless of how much they drive or how much fuel they purchased—to keep the “trust fund” solvent.

To put that number in perspective, the total price tag for the entire five-year 2005 federal transportation law (SAFETEA-LU) was only $244 billion. The reality looks even worse if you start to consider its status without those nine transfers:

The “user pays’” principle isn’t on life support—it died a long time ago.

Here are two basic reasons why:

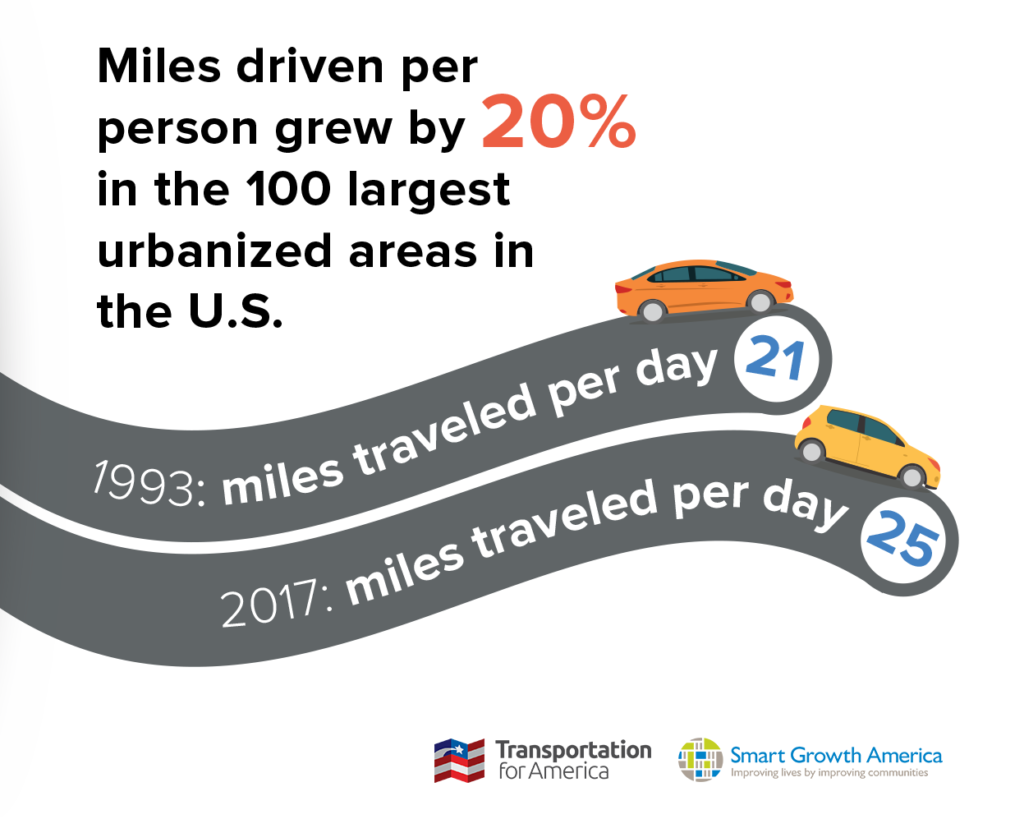

First, the gas tax hasn’t increased since 1993, even as the fuel efficiency of vehicles has improved, and inflation has steadily reduced its purchasing power. 4

This means that annual gas tax revenue declined by $10 billion per year from 2010 to 2025. There’s also compelling evidence that the largest factor in the erosion of gas tax value “is the massive increase in road construction costs—the cost-per-mile of the United States highway system grows larger each year.”

Second, 2008 was also the beginning of a structural imbalance created by how much the gas tax was bringing in and (most importantly) how much money Congress was committing to spend each year. Rather than keeping overall spending matched 1:1 to the amount of gas taxes projected to come in, Congress has continually committed to spending far more than the gas tax brings in. State DOTs received 50 percent more in flexible formula funding in the 2021 IIJA compared to the 2015 FAST Act, which was itself a 15 percent increase over MAP-21 in 2012. All while gas tax revenues were failing to grow at the same rate.

Everyone has paid to fill the gap since 2008, whether you’ve ever bought a gallon of gas

Back in the late 2000s and early 2010s, the loudest debate during reauthorization was about the states who received more gas tax revenue back than they paid into the program. But because of the $275 billion taken from all taxpayers to plug the gaps in the trust fund, this phenomenon simply no longer exists. Every state is receiving more than they paid in gas taxes. The Congressional Research Service estimates that more than a quarter of all “trust fund” spending has come not from users but from general tax dollars or other sources since 2008. That number has gotten worse in recent years: when it expires in 2026, close to a third of all IIJA spending will have come from sources other than users.

And despite what you will surely hear about the #1 problem being that we spend gas tax revenues on non-highway projects, Congress is spending $20 billion more per year than the gas tax brings in on highway formula programs alone.

One more time: The trust fund and its core concept are not mostly dead; they are completely dead.

What’s next for the trust fund

Because of this looming fiscal fiasco, the loudest refrain you will hear from the transportation industry and lobby groups and Congress over the next two years will be about money. You won’t hear much about making dramatic changes to get better outcomes out of this program, but you will see headlines and quotes about how we need to “find more money,” and “solve the funding issue,” and “address the trust fund’s insolvency.” Indeed, the trade group representing state DOTs has already staked out this position: We absolutely must grow the size of this bankrupt program, and taxpayers (every one of you!) need to collectively find $210 billion for them to keep doing the same thing that fails to deliver results. AASHTO’s proposal:

Why is the default assumption that we have to continue increasing the size of a program that no longer pays for itself while failing to deliver on what matters?

There are only three basic options for moving forward

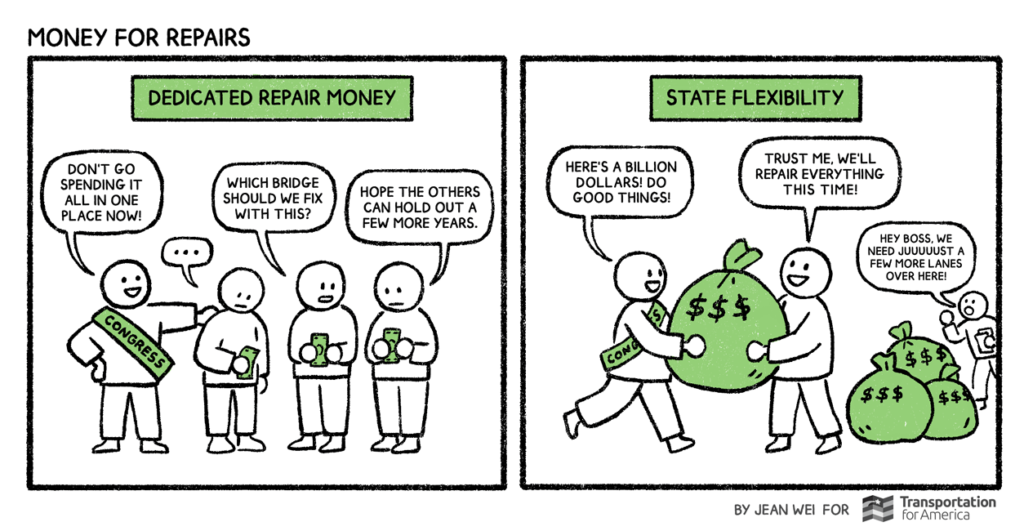

As Taxpayers for Common Sense wrote a few weeks ago, “the Highway Trust Fund’s looming insolvency is not just a transportation problem—it is a taxpayer problem.” There are three broad options at this point:

- Take billions more from all taxpayers (whether they buy gas or not) by deficit spending, transferring billions into the trust fund, and having all taxpayers pick up the tab

- Take billions more from taxpayers by raising revenues in some fashion (increasing gas taxes or establishing new taxes)

- Cut the size of the program’s spending down to the amount of revenue brought in each year and live within our means

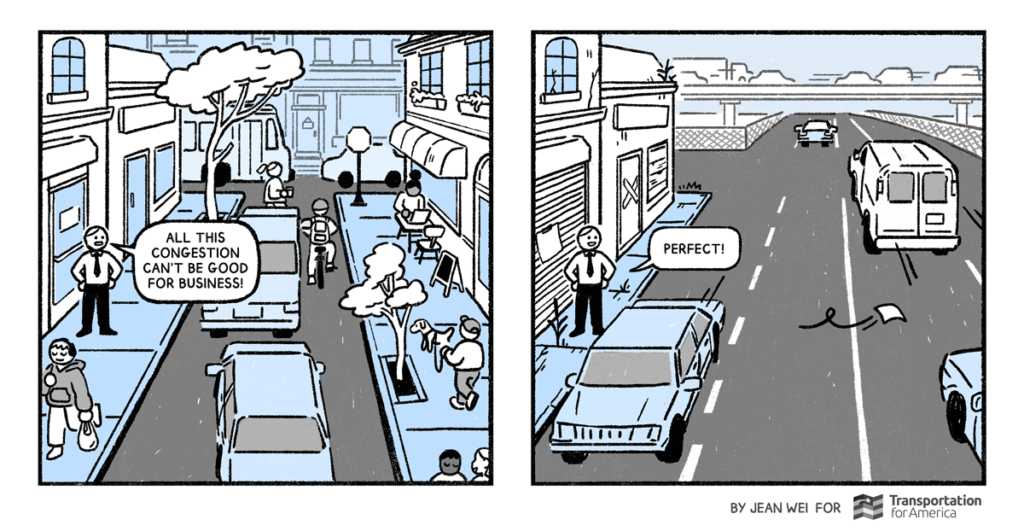

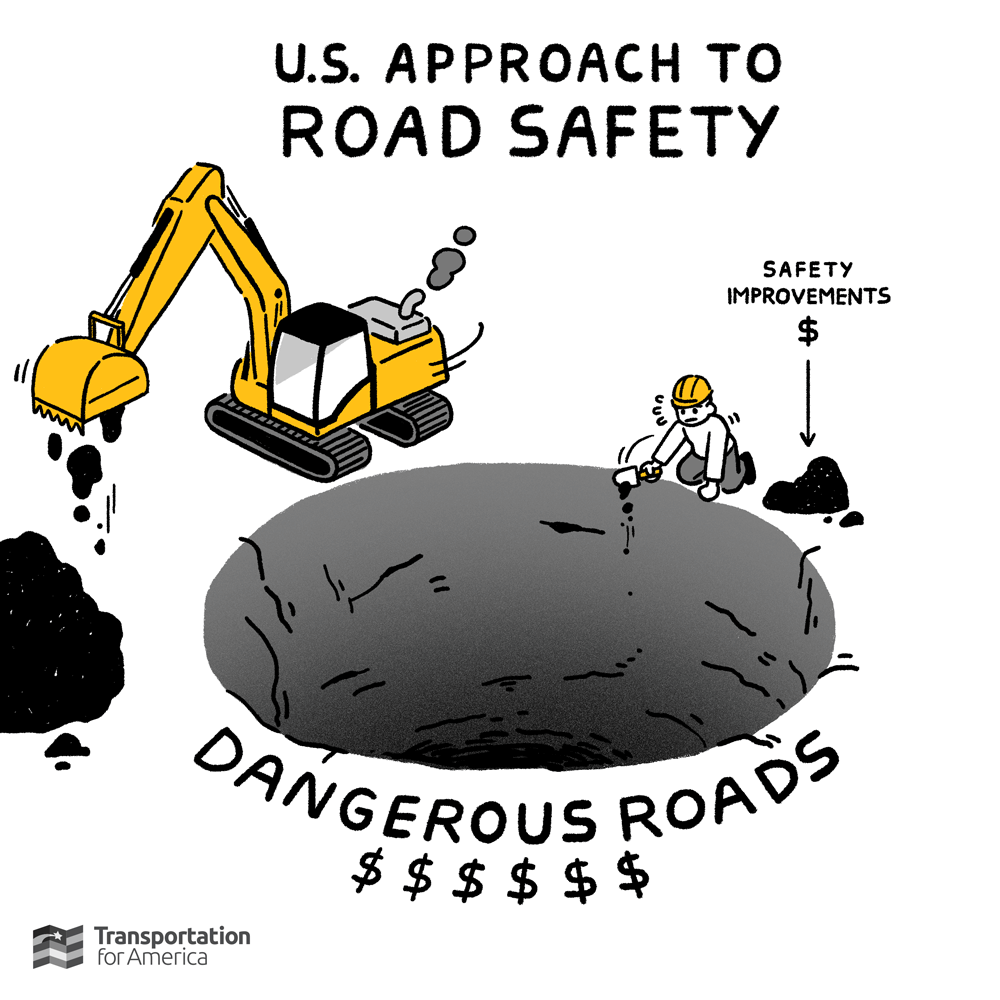

These first two options require taking more money from taxpayers to prop up a federal program that is failing to move the needle on repairing our crumbling infrastructure, reducing congestion, reducing emissions, or improving safety.

It’s time to start thinking about that third option: Scale the program down to the size of what the gas tax brings. Similar plans have been suggested before, including a slightly different 2014 proposal by Senator Mike Lee (R-UT) and 28 Senate Republicans to mostly phase out the federal gas tax—except for a few cents to fund interstate maintenance and repair only—and leave it to states to make up for the lost funding.

End this program as we know it

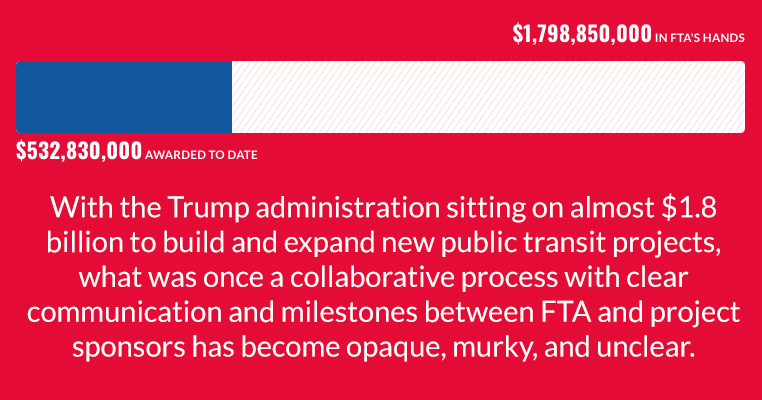

There was a time in T4America’s history that we joined the chorus of those who thought Senator Lee’s above idea was a terrible one. Back then, we believed—as a lot of others still do—that we just had to accept billions in destructive highway building and bad outcomes in order to get some transit funding, pennies for bike lanes or sidewalks, or competitive grants for creative, multimodal projects. But we simply cannot continue ignoring this program’s damage and terrible performance.

It’s time to wind down the federal program.

As we say in our platform for reauthorization, “this program doesn’t need a facelift; it needs to be blown up and replaced with something completely new.” It has completely failed to deliver on its promises, and it’s taken obscene amounts of money from all taxpayers above and beyond what vehicle owners pay at the pump to do it.

Scaling the program down to the size of incoming gas tax revenues is probably the best first step toward transitioning to a radically different federal program oriented around setting priorities, picking projects that will deliver on those outcomes, and providing greater accountability for taxpayers. This is the only conversation about funding that T4America will be having: What are the best possible options for scaling down the federal transportation program and creating something new?

This program has been a bad deal for a long time, and it’s time we stop accepting it. It’s not time to rescue the trust fund, it’s time to write its eulogy.