Congress is starting to talk about the next federal transportation bill, due next year. But they seem more concerned with how the money is distributed, to whom, and how fast it is being spent, rather than what the American people are getting for their tax dollars.

With the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) sunsetting in 19 months, Congress has to prepare a bill to reauthorize the federal highway, transit and rail programs. But numerous committees so far tasked with that work have not even started to consider the most fundamental question: how well is the highway system working?

The federal government has spent $1.5 trillion of American taxpayer dollars over the past 30-plus years to build a world-class surface transportation system. In 2012, a strong bipartisan majority—373 to 52 in the House and 74 to 19 in the Senate—passed a transportation reauthorization bill that refocused the program on national transportation goals, increasing accountability and transparency, and improving project decision-making through performance-based planning and programming.

The seven national goals Congress wrote into law (23 USC 150) finally captured the priorities that have been highlighted since 1991: safety, infrastructure condition, congestion reduction, system reliability, freight movement and economic vitality, environmental sustainability, and better project delivery. After 34 years of increasingly spendy bipartisan transportation bills, how have we fared on these goals?

Safety

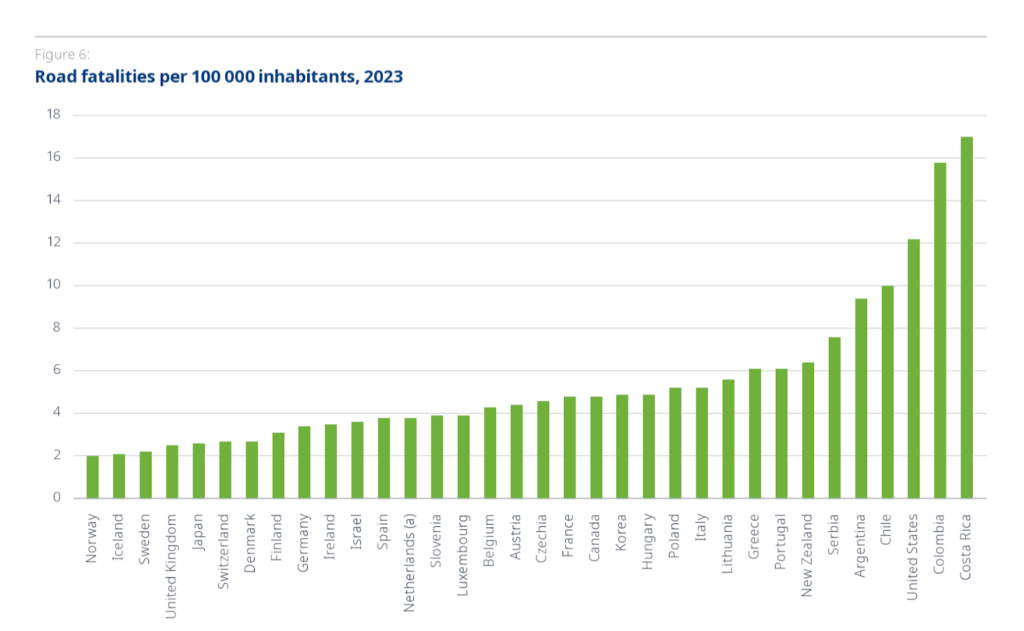

The United States has the most dangerous roads in the developed world. By a lot. Twice as deadly as Greece, three times as deadly as Israel, and six times as deadly as Norway. In fact, the U.S. is twenty percent more deadly than Chile and 30 percent more deadly than Serbia. Most of these countries are getting safer, but not us.

Roads in the United States are so deadly and unsafe that our numbers change the narrative on worldwide traffic safety in the developed world. The 2024 roadway safety report on the 70 countries in the International Traffic Safety Data and Analysis Group (IRTAD) notes that overall road deaths would have actually fallen by 12.8 percent if the US had been left out. We are dragging the performance of the rest of the developed world in the wrong direction.

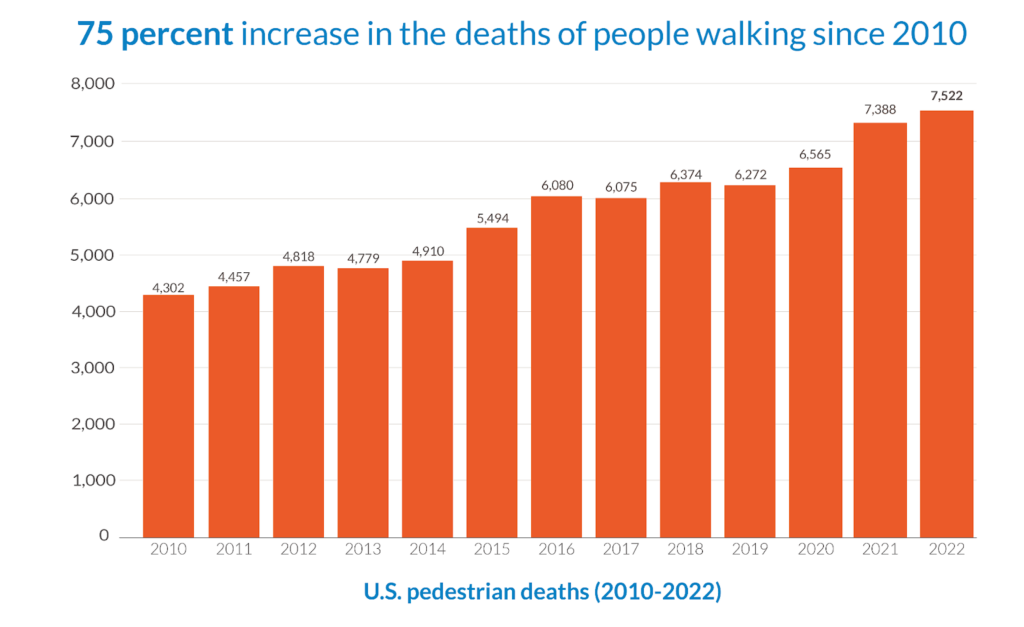

For people walking, it’s even worse. Compared to a 29 percent improvement in the rest of these countries, pedestrian fatalities in the US have increased 75 percent since 2010, which you can find in the National Complete Streets Coalition’s report on pedestrian safety, Dangerous by Design.

While the federal transportation program has included a specific program to address safety, the Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP), which has existed since 1973, has always been a tiny part of the overall program—currently, 6 percent of the highway program. Add in the Transportation Alternatives program, which helps build sidewalks and other infrastructure to help people without a car get around safely, and you get up to 9 percent. Whatever constitutes our approach to safety is failing for everyone who uses the road.

Congestion reduction/Reliability/Freight

USDOT chose to assess congestion reduction, system reliability, freight movement, and economic vitality through overly simple measures of vehicle speeds, so we will address these areas together. One of the biggest excuses for not taking established steps to improve safety (the steps every nation doing better than us is taking) is the need to support the economy by eliminating congestion. Saving lives with slower speeds has taken a back seat in favor of trying to eliminate congestion at all costs, which has been the ultimate goal of all federal transportation spending for the last 30 years. Yet, no matter how you measure this effort, it has failed.

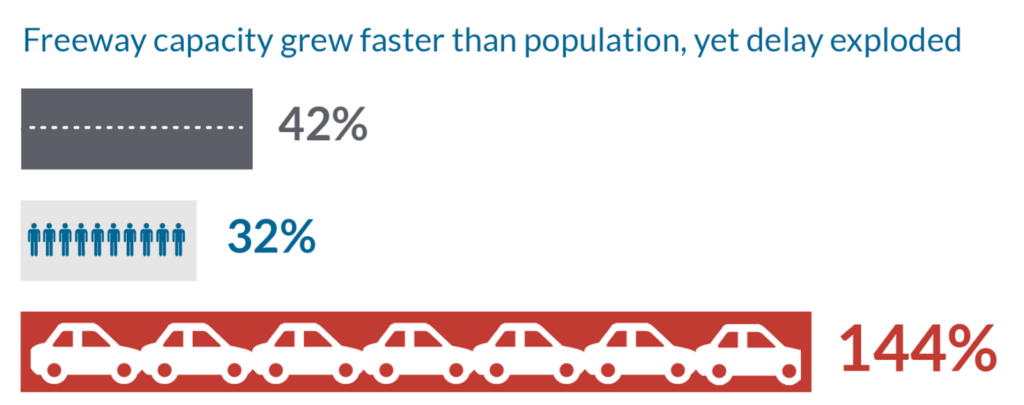

Between 1993 and 2017, the most populous 100 U.S. cities added 30,511 new freeway lane-miles, an increase of 42 percent. That rate of freeway expansion significantly outstripped the 32 percent growth in population in those regions over the same time period. So congestion should have gone down, right? Nope, it went up 144 percent. Congestion increased in every single one of these 100 metro areas. It went up in places that tried really hard to build their way out of congestion, like in Brownsville, TX, where the population increased 73 percent, they increased freeway lane miles by 287 percent and congestion increased by 1230 percent. It also went up in places that lost population, like in Detroit, MI, where the population decreased by 5 percent, they increased freeway lane miles by 15 percent, and congestion still increased by 45 percent. Let that sink in. Fewer people, more highways, and congestion increased—a lot!

Infrastructure condition

What have record levels of investment in infrastructure gotten us when it comes to the basic condition of our roads and bridges? USDOT’s Conditions and Performance Report for 2024 found that the share of federal-aid highway pavements with good ride quality improved during the 2008–2018 period—from 40.7 percent to 47.2 percent (not even half). But the share of federal-aid highway pavements with poor ride quality also worsened during that time, rising from 15.8 percent to 22.6 percent. In terms of bridges, the share of federal-aid bridges in good repair decreased from 47.8 percent to 46.0 percent; however, the share of federal-aid bridges in poor repair also decreased from 10.1 percent to 7.6 percent. Pretty lackluster results.

USDOT likes to note that the busiest roads (by amount of vehicle miles traveled) are in (slightly) better condition, as they likely have more repair dollars spent on them. While this is true, either all roads you’ve built are important enough to maintain, or they should not have been built in the first place. This claim also runs directly counter to rhetoric often deployed about the “importance” of rural areas—as if it’s ok if their less trafficked roads are poorly maintained.

Emissions

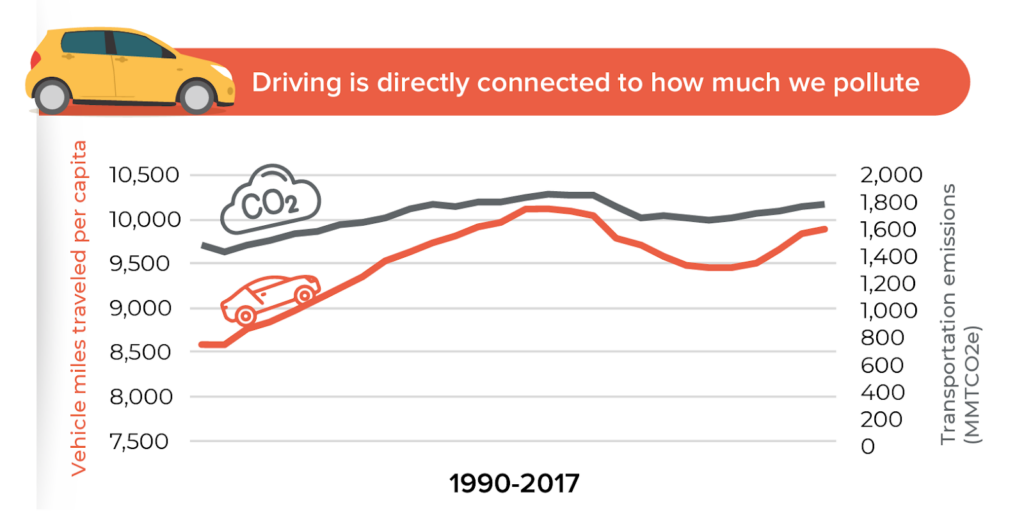

We covered this just two months ago. Based on current investment patterns, over the course of the current infrastructure law, federal surface transportation spending could increase emissions by nearly 190 million metric tonnes of emissions over baseline levels through 2040 from added driving. This is the emission equivalent of 500 natural gas-fired power plants or nearly 50 coal-fired power plants running for a year.

And we weren’t doing well before the IIJA either, as we showed in our 2020 report, Driving Down Emissions.

Speeding up project delivery

Why would we want to speed up the delivery of projects producing such terrible results? Slow them down. Stop them.

Members of Congress preparing the replacement of the IIJA this year and next should be warned that the collective failure to make improvements in these priority areas will be given as the primary reason to pump more money into the same programs we have been funding for decades. They may have changed names, shifted from formula to discretionary or vice versa, or seen their proportions change, but they are basically the same programs.

If you point out that the results have been truly disappointing, you will hear how the transportation agencies aren’t to blame, even as they ask for more money to do the same things. For example, we regularly hear that roadway fatalities are up because of the misbehavior of people using those roadways rather than the design or function of those roads. Their counterparts in other countries don’t feel that way, which is one reason they are successfully saving lives. If state DOTs aren’t able to improve safety, then we should give funding to other entities that can.

Senator Shelley Moore Capito, whose committee will be writing a large chunk of this law, is starting with the wrong questions and assumptions. She told POLITICO that she wants to look at formula vs. discretionary to see if the discretionary [grants] getting out and to determine kind of efficiencies need to be made. The most essential question to ask is whether or not the enormous amount of spending on transportation has resulted in better outcomes, like the goals Congress overwhelmingly supported and put into the U.S. Code: making the roads safer, reducing congestion, improving infrastructure conditions, and reducing emissions. If the answers are no, then clearly it’s time to stop throwing good money after bad.

Congress is looking at spending another $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years. People will point to the overwhelming bipartisan support. Inevitably (as happens at every reauthorization), there will be calls for more money for the same programs, more flexibility for states to spend federal funds however they like, and less accountability overall.

This strategy has failed to deliver, and it won’t deliver anything different, whether we give it more money or less.

We shouldn’t spend another dime on a program that fails so completely to deliver on all of the priorities we have set for it. This is the issue that Congress should be grappling with over the next year as they prepare the next transportation law.