Billions of dollars in new federal highway funding are flowing into road safety programs, so we wanted to review the research on which interventions can save lives on America’s roads—and which are failing to do so. All the available data tell us one thing clearly: strategies that fail to accept human error and reduce speeds also fail to reduce road casualties.

Much of the research in this post comes from a capstone project on transportation safety and enforcement by Mae Hanzlik, SGA Senior Program Manager of Thriving Communities, completed during her time at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Around 40,000 people died on America’s roadways in 2020. Many state and local departments of transportation, encouraged by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), choose to address this crisis by educating drivers, increasing the enforcement of traffic laws, and promoting automated driving technology. But as Smart Growth America’s Dangerous by Design report notes, year after year, traffic fatalities continue to rise. Each of these approaches has its place, but they all have something in common: they focus on addressing human error, and they fail to acknowledge that mistakes are an inherent element of driving.

This fundamental misunderstanding is fatal, leading to higher speeds and more roadway fatalities, increasingly in recent years. We’ve pulled together all the available data to set the record straight. Strategies that fail to accept human error and reduce speeds also fail to reduce road casualties.

This post is the first installment of a series on road safety programs. For design solutions that can make mistakes less fatal, watch for part II and III.

Education

One of NHTSA and state DOTs’ favorite traffic safety interventions is public awareness and education campaigns like the ones below. These types of slogans can be found plastered across billboards along most state highways and interstates, begging drivers to stop speeding. Advertisements like these are often accompanied by direct outreach through new driver education programs in high schools across the country.

Some public awareness campaigns, like those that encourage parents to secure their young children in child safety seats while driving, can be effective. But broader, more vague efforts to get drivers to slow down, make bicyclists wear helmets, or have pedestrians wear high-visibility vests have failed to reduce roadway injuries and fatalities.

State and federal regulators seem to believe that drawing a public connection between behavior and safety will encourage safer driver behavior. But a sweeping 2008 report from the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) found that “information-only programs are unlikely to work, especially when most of the audience already knows what to do.” Drivers know what unsafe behavior looks like, but on roadways that are designed to allow for speeding, doing so is often the most convenient choice.

New driver education programs, despite being much better targeted at the needs of their audiences than general public awareness campaigns, are not much more effective. In a University of North Carolina evaluation of North Carolina’s Kindergarten-9th grade child traffic education program, researchers found that despite a “significant increase in students’ traffic safety knowledge…behavioral observations failed to reflect this increased knowledge.”

Researchers have found the same phenomenon to be true for older teenagers in licensure programs, whose lessons learned in driver education programs have limited impact when they encounter roadway designs that incentivize unsafe driving. This stark difference between what young drivers are taught about driving the speed limit and the reality of roads built for speed creates a dangerous contradiction, which NHTSA itself readily admitted in a review of local programs. Of course, driver education programs are necessary to introduce new drivers to the rules of the road. But leaning on them as catch-all solutions to skyrocketing road fatalities is likely to be ineffective at best and counterproductive at worst.

Public safety awareness and education campaigns, often defended as benign public services, require a lot of cash. They cost federal and state agencies millions of dollars a year, money that could be better spent on evidence-based approaches to road safety.

Enforcement

Law enforcement plays a major role in today’s traffic safety paradigm. Police reports are the basis of most traffic violation data. And though cities like Washington, D.C. are trying to take traffic enforcement out of the hands of police officers by giving it to other agencies or automating it, most areas around the country require all moving violations to be enforced by uniformed, armed police officers.

This approach often harms the communities it seeks to protect. Any limited ability that law enforcement has to make our roads safer is diminished by the harm that it causes in the process. Law enforcement officers killed over 400 non-violent drivers and passengers during routine traffic stops between 2016 and 2021. These impacts fall disproportionately on Black people.

Police reports are not accurate reflections of the causes of vehicle crashes. By nature, police reports focus on individual behavior, aiming to attribute blame to people involved. They fail to acknowledge the role of road design and vehicle size in crashes. For example, if a pedestrian is struck by a vehicle while crossing the street mid-block because the next crossing is a mile away, the police will often blame the pedestrian for not obeying the law. These faulty data lead policymakers to design solutions that try to correct for individual behavior rather than trying to better understand behavior as a symptom of a larger problem.

Organizations like the American Public Health Association and the Center for Policing Equity have called for and suggested more equitable forms of traffic enforcement. New ideas like these are worth considering.

Technology

Since the invention of the automobile, improved vehicle safety features have saved countless lives. But most of these advancements, like seatbelts, airbags, and frontal and side impact testing have focused on the safety of those inside the vehicle in the event of a crash, doing little to prevent crashes themselves.

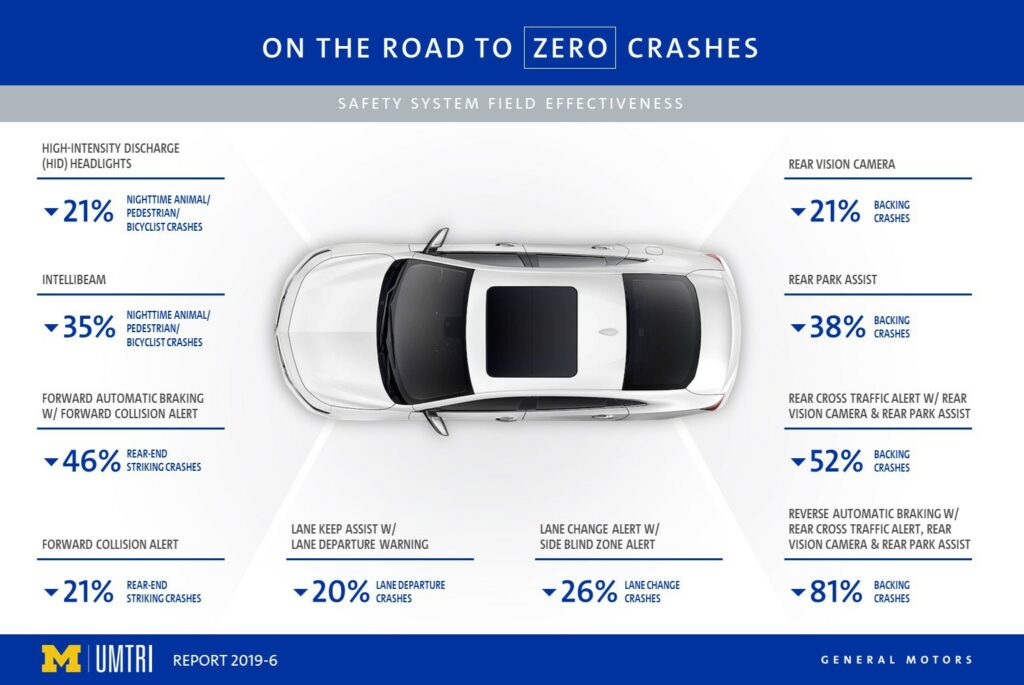

With skyrocketing fatalities among vulnerable road users (like pedestrians, cyclists, and wheelchair users), though, NHTSA and other authorities have championed some new driving systems, namely Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) and Automated Driving Systems (ADS), as solutions. ADAS and ADS are technologies that can help drivers detect road obstacles and avoid them before the driver can react themselves. Companies like General Motors have even touted their features as a step toward a “vision of zero crashes.”

But the reality of these systems is a lot more complicated. Most vehicles equipped with ADAS or ADS allow drivers to disable those systems. A study by J.D. Power indicates that many drivers are opting to disable their ADAS or ADS out of annoyance. But even when ADAS or ADS are active, their safety benefits are dubious. These systems routinely fail to detect the presence of children, as well as people of color and those with disabilities. Children, people of color, and people with disabilities are far more likely to be killed as pedestrians, so these advanced driving systems have the potential to deepen the inequities on America’s roads.

Tesla’s ADAS/ADS systems, some of the most popular on the road today, have resulted in hundreds of road fatalities each year. California’s Department of Transportation had to confront Tesla after that company’s ADAS systems, often advertised as fully autonomous vehicles, resulted in several manslaughter charges being filed against drivers that abdicated their driving responsibilities to their “autonomous” systems.

So without significantly more regulations on ADAS/ADS, their benefits will be minimal and they might actually be counterproductive, since human error is nearly impossible to eliminate from the act of driving, at least with current technology. Policymakers should consider this fact before entrusting the safety of American roadways to new technologies.

So what?

The widely-accepted paradigm of changing driver behavior through education, enforcement, and technology is not making road users safer. So wherever these strategies are currently being implemented, policymakers and regulators should seriously consider whether they are accomplishing desired safety outcomes. Advocates should persistently ask their state and local governments: “Where’s the evidence that you’ve been able to reduce driver error?” Most of the time, the answer will be: “There is none.”

But calls to reduce these ineffective measures are likely to be ignored without alternatives that actually reduce roadway crashes. By accepting the fact that humans will make mistakes, we can plan for those mistakes and make all road users safer by preventing them. Stay tuned for part two and three of this blog series to see how design interventions can get at those solutions, and further advice for advocates who want to push for change.

11/2/22 edit: A previous version of this post erroneously cited a University of North Carolina study as an evaluation from the Transportation Research Board. This post has been updated.

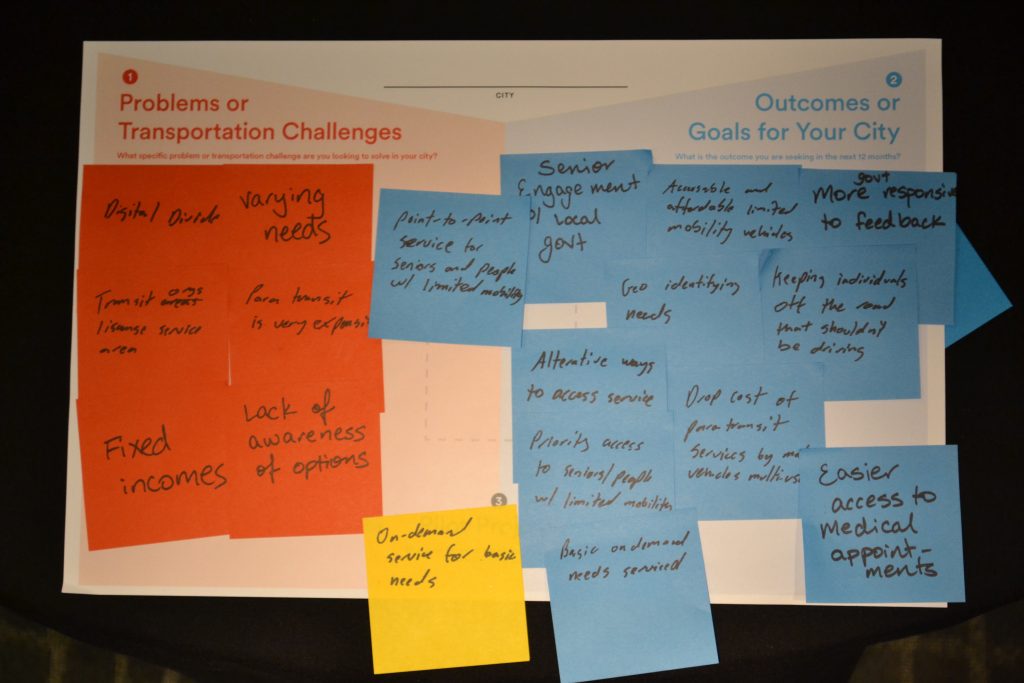

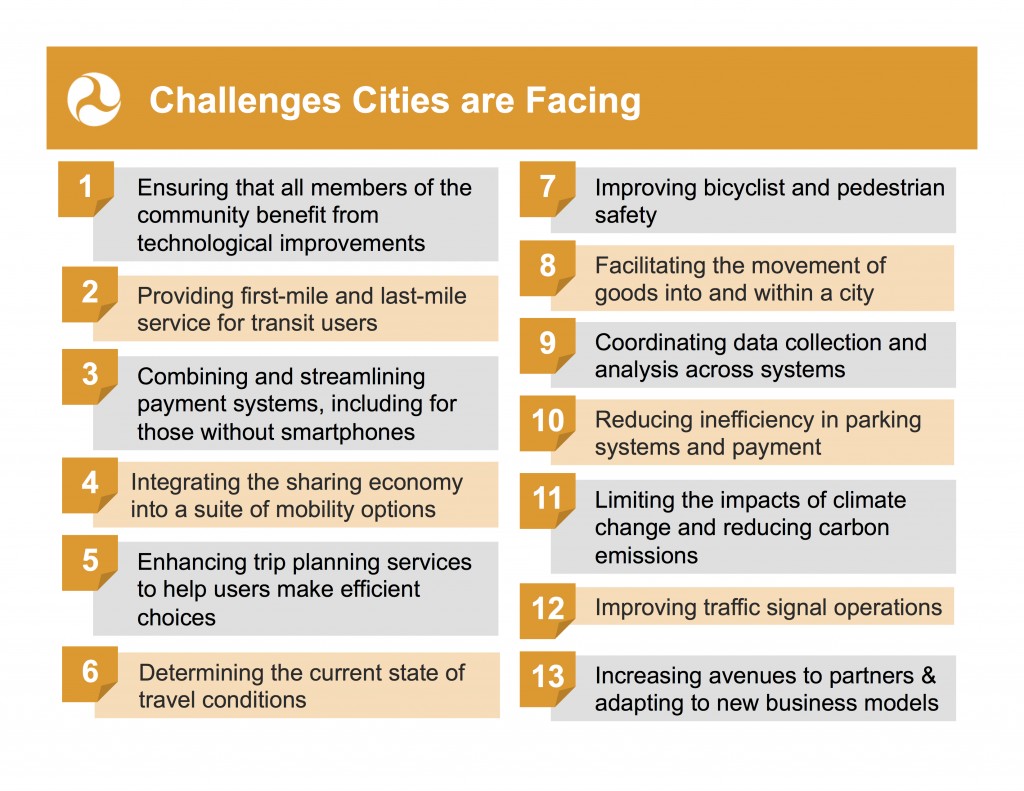

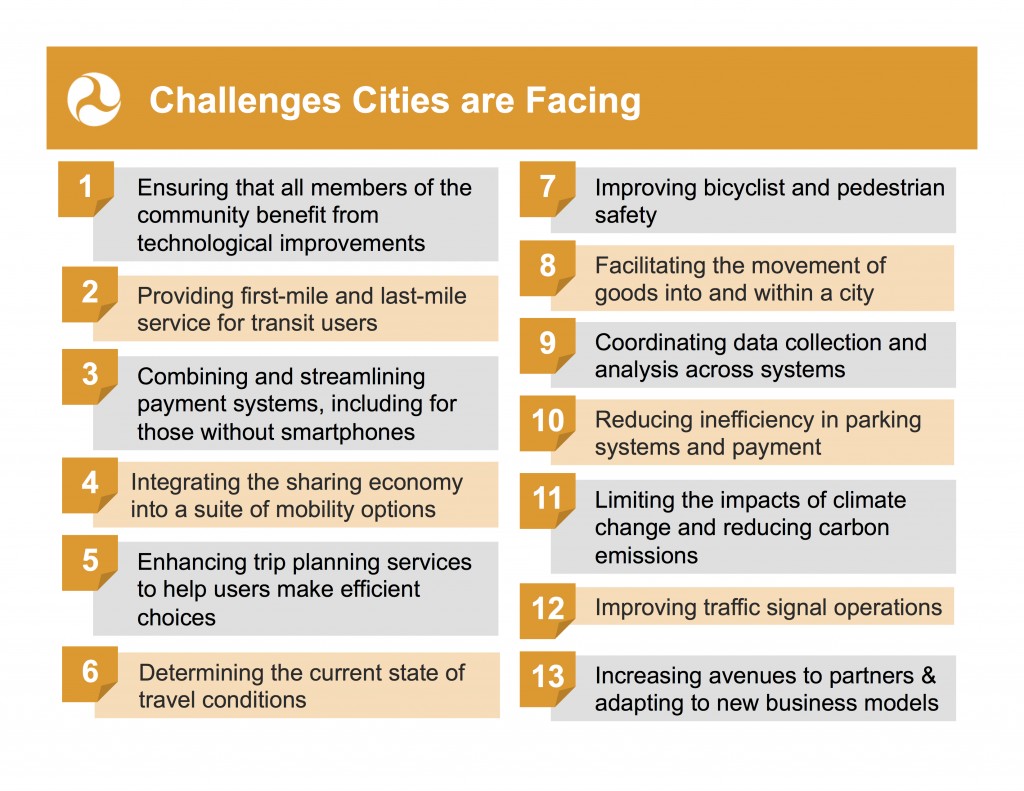

Much of that conversation centered on how cities can drive the discussion and lead at the state level on those policies that will have the largest impact on our cities. Keynote speaker Seleta Reynolds, the head of the LA Department of Transportation, reminded the participants that, no matter what policy levers are controlled by the state, cities still have an enormous amount of leverage — if they’re willing to work together and think outside of the box.

Much of that conversation centered on how cities can drive the discussion and lead at the state level on those policies that will have the largest impact on our cities. Keynote speaker Seleta Reynolds, the head of the LA Department of Transportation, reminded the participants that, no matter what policy levers are controlled by the state, cities still have an enormous amount of leverage — if they’re willing to work together and think outside of the box.