Late last week the House released their new five-year proposal for transportation policy and spending, known as the INVEST in America Act. By focusing on making tangible progress on outcomes like repair, safety, climate change, and access to jobs and services—rather than just asking for more money for more of the status quo—House leaders have again proposed a paradigm shift in how we spend transportation dollars and measure what they accomplish.

The first, most important thing to know about the new Invest in America Act is that it’s quite similar to the INVEST Act, which was approved by the House in the last Congress but which failed to advance to the Senate. This new bill picks up where the INVEST Act left off, repeating almost all of the good provisions and making improvements. As we said in our statement last Friday about the bill, “this is a paradigm shift from the approach of the last 30 years of proposing small, exciting new programs to fix recognized problems while allowing the much larger core program to exacerbate and further those same problems.”

It’s the kind of fundamentally new approach we need.

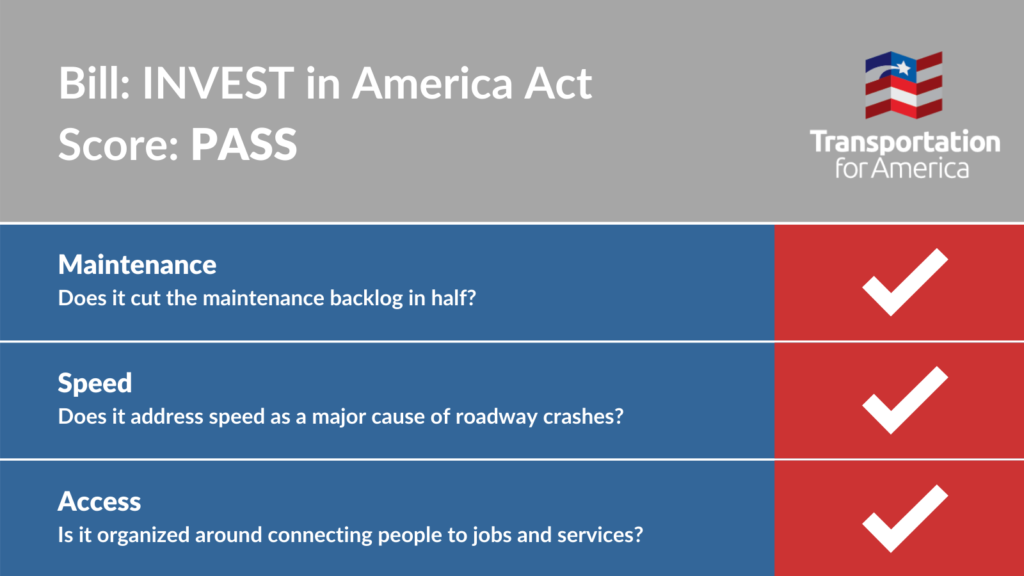

As we’ve done with every infrastructure proposal or long-term policy proposal for the last few years, we’ve produced a scorecard for the bill to measure how the Invest in America Act starts to redirect transportation policy toward T4America’s three core principles of 1) maintaining the current system, 2) protecting the safety of people on the roads, and 3) getting people to jobs, schools, groceries and health care.

1) Prioritizes maintenance first in nearly every program

We can’t keep choosing to expand with no plan to maintain. We’ll never make progress on our infrastructure if we don’t start prioritizing the care of the valuable assets we’ve spent decades and billions of dollars building.

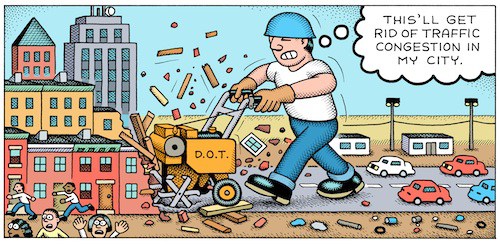

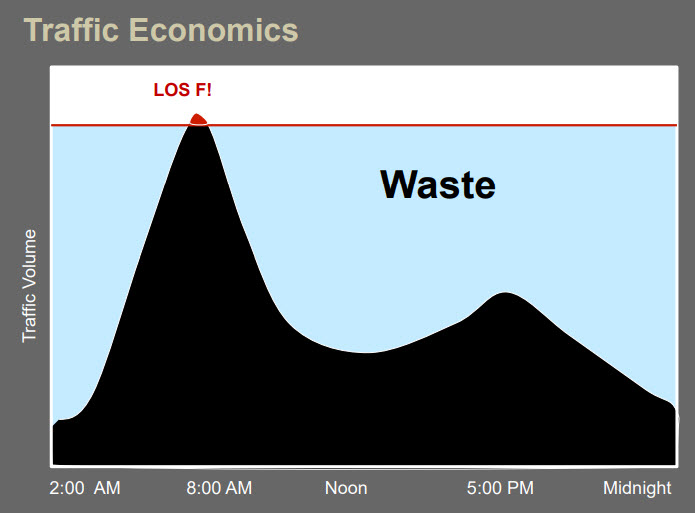

As we wrote last summer, we’re “expending money we don’t have to build roads we can’t afford to maintain which fail to bring the promised economic returns—all while neglecting repair needs.” While our preference would be to cut maintenance backlogs in half by dedicating formula dollars to maintenance, this bill finally brings the kind of focus on repair that we need, pushing transportation agencies to prioritize maintenance across the board in core programs—the most important way to make repair a priority—while also creating some new repair programs. This stands in sharp conflict to the Senate approach which favors providing state DOTs the flexibility to ignore their repair needs in order to build new things they can’t afford to maintain.

As an example of that approach, for one of the two largest programs typically used on highways (the National Highway Performance Program), this bill requires project sponsors to have a plan to maintain any proposed new capacity while making progress toward their state of repair goals. Overall, this bill maintains the INVEST Act’s language requiring a long-term maintenance plan for any proposed new capacity project and a record of improving their state of repair, includes a provision requiring states to spend no less than 20 percent of their main highway programs on bridge repair, creates a new programs to fix bridges and a $1 billion program for repairing rural bridges, adds a unique program to prioritize replacing the oldest buses, and creates other new programs focused on the maintenance of rail crossings, bridges, and tunnels.

2) Institutes a comprehensive approach to safety

Designing for safety over speed is our second principle, with a call to save lives with road designs that support and encourage safer, slower driving.

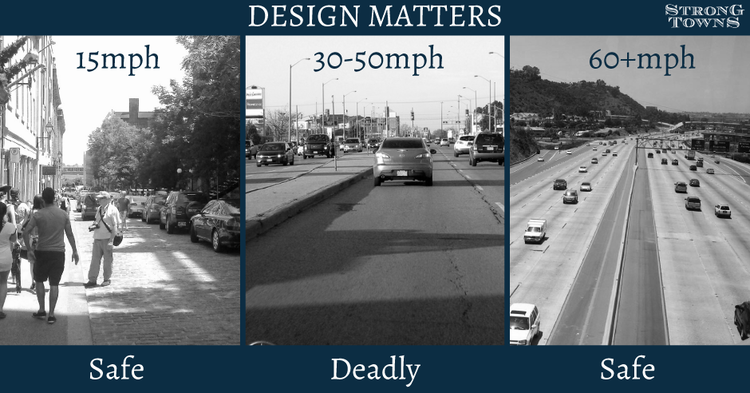

The conventional approach to designing highways—wide lanes and wide roads to allow for high speeds—has resulted in the highest number of people being struck and killed while walking and biking in three decades, in addition to a record rate of in-vehicle fatalities in 2020 as traffic evaporated and speeds increased. Our roads are deadly by design, and safety needs to supersede moving cars fast at all costs.

Last summer’s INVEST Act was strong on this count, and this bill maintains almost all of that positive language, which might be easiest to digest in a list of bullets:

- It removes states’ current ability to set negative targets for safety, i.e, planning for more people to die on their roads next year with the money they spend. This stands in stark contrast to the Senate bill which continues to provide states with the “flexibility” to continue with this practice, with no penalties and certainly no concrete, accountable goals for saving lives and reducing deaths.

- It will no longer require states to use the unreliable sorcery of traffic modeling that so often results in prioritizing speed and vehicle throughput over peoples’ lives.

- The Transportation Alternatives Program, which is used to make walking and biking safer and more convenient, is popular and oversubscribed in almost every state, where localities have to apply to the state for funds. Yet some states either sit on this money or transfer it into conventional road-building projects, a practice which will be curtailed by this bill.

- The Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP) gets a new focus on vulnerable users and a push toward what’s known as a safe systems approach.

- To create plans for Complete Streets and Vision Zero plans—an effort to completely eliminate traffic fatalities, in part through street design—states would be able to use a variety of federal funds for those efforts, including the HSIP program above.

- Lastly, the 85th percentile rule for setting speed limits gets tossed, and states would instead be required to set speed limits with a consideration of the community surrounding the corridor, the number of bicyclists and pedestrians, and crash statistics (as opposed to just traffic conditions). Right now (with the 85th percentile rule), speed limits are set by how people behave; so if you build a wide street and people drive too fast, the speed limit is often raised to accommodate the rule breakers, showing just how pernicious the focus on speed over safety is with the current program.

This bill will most certainly create a safer transportation system and save lives. We may dive into the safety provisions in more detail in a longer post, so stay tuned.

3) States and metro area planners must determine how well their system connects people to jobs—drivers and non-drivers alike

If the goal of transportation spending is to connect people to jobs and services, then that must be measured and considered when funding decisions are made. Our third principle is measuring transportation success by how many jobs and services people can access, rather than the blunt and outdated assumption that cars being able to drive fast on specific segments of road equals success.

As with the INVEST Act last summer and for the first time at the national level, recipients of federal transportation funding will be required to measure how well their system connects people to the things they need, whether they drive, take transit, walk or bike. State DOTs and MPOs must consider whether people traveling (not just driving) can reach jobs, schools, groceries, medical care and other necessities, collect that data, and also make it available. And they will be penalized if they fail to use federal funding to improve that access.

This is truly groundbreaking stuff, and while there’s far more under this umbrella to highlight in a longer post, this represents a massive shift to how we currently spend money on transportation, which is largely unhinged from producing any sort of measurable improvement in access for everyone who uses the system.

—

We will be taking some longer looks in a follow-up post at how the bill will impact other important areas beyond our three principles, like climate, equity, transit, passenger rail, and others, so stay tuned.

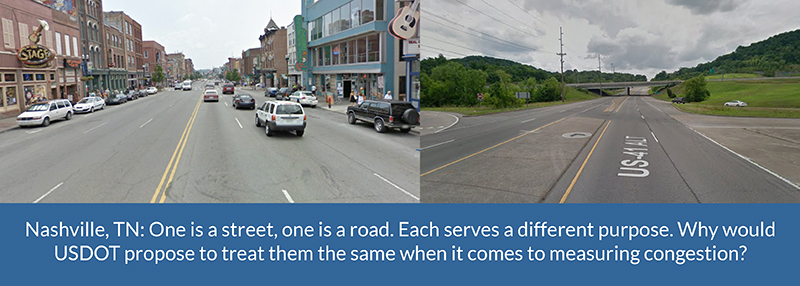

he new criteria recognize that successful streets running through a bustling downtown of any size need to be designed far differently than rural highways connecting two towns or cities. They have to meet a far more diverse range of needs than simply moving cars fast, and these smart new guidelines reflect that wisdom.

he new criteria recognize that successful streets running through a bustling downtown of any size need to be designed far differently than rural highways connecting two towns or cities. They have to meet a far more diverse range of needs than simply moving cars fast, and these smart new guidelines reflect that wisdom.