Transit Equity Day—which honors Civil Rights Leader Rosa Parks—is on February 4th. As we celebrate the importance of ensuring people of all backgrounds and abilities are able to use transportation, it is imperative to highlight communities that are often left out of the public transit conversation: rural communities.

Source: AARP.

All communities and people deserve transit options to ensure their greatest well-being. Access to high-quality and reliable public transportation is foundational to ensure everyone can access essential destinations like schools, healthcare facilities, and jobs. Traditionally, transportation advocacy is seen in urban and metropolitan areas where density is plentiful, and the demand for transit is loud. However, rural communities are lost in the conversation, perceived as areas that do not need access to transit due to the sprawling nature of the communities and assumed access to private vehicles.

A Complete Streets approach is needed—and can be made possible—in rural communities. Learn more about how to create safe and inclusive small towns in this video.

In reality, more than one million households in rural areas do not have access to a car. In fact, the majority of counties with zero-car households are in rural communities, highlighting the brazen need to invest in public transit. The lack of transportation access leads to a decreased quality of life with barriers to access community amenitites, healthcare resources, and schools. However, studies have repeatedly shown that people in rural areas are equally as likely to walk and bike as those in urban areas if they have access to safe and reliable options to do so. In spite of this, investments in transportation networks that support walking, biking, and public transit are largely limited to urban communities. There are a lot of affordable, attainable solutions to encourage active and multimodal transportation in rural America. Implementing Complete Streets, more effective and multimodal-oriented land-use approaches, and strategic transit planning would all result in more mobility options for residents, as well as significant benefits, including healthier and more economically prosperous places.

A critical part of the strategic planning process includes developing a vision for a community that is tailored to its unique needs and features building partnerships with community groups, agencies, and individuals that will help realize this vision. Having land development policies and guidelines in place is also key to producing strong economic outcomes and vitality in the long term.

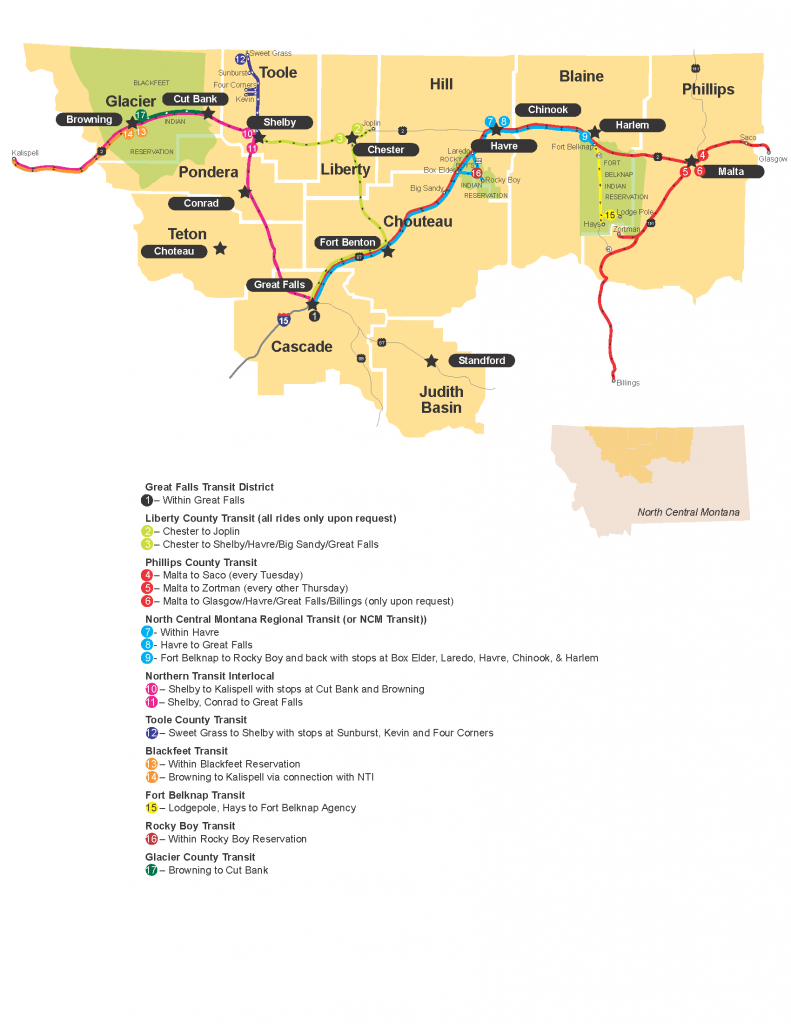

Strategic innovation also ensures the availability of viable and affordable transit for underserved regions. A study in rural New Mexico examined the feasibility of microtransit implementation in the area, finding that community engagement accompanied with diverse funding strategies was key to achieving success. Other examples of such efforts include the Blackfeet Indian Reservation’s micro-transit service in northwest Montana or the City of Wilson’s RIDE service. Innovative, shared mobility options that go beyond traditional buses, like bikeshare systems or vans, can offer flexible options that serve the unique needs of rural communities.

Transit Equity Day serves as a reminder for local leaders and planners to prioritize transit investments in rural communities. By fostering equitable access to transportation options in rural communities, we can build more resilient areas where everyone can thrive.

Transit conference where all jurisdictions (save one) supported putting a measure on the November 2018 ballot to expand the Twin Transit district to include all of Lewis County.

Transit conference where all jurisdictions (save one) supported putting a measure on the November 2018 ballot to expand the Twin Transit district to include all of Lewis County.