Juxtaposed by a well-supported bike ride from San Francisco to Los Angeles, there are many people in rural communities, particularly agricultural workers, along the route that are in critical need of vital, reliable, affordable transportation options, and suffer dire health and economic consequences as a result.

The 2022 AIDS/Lifecycle bike ride (June 5-11, 2022), a seven-day, 545-mile ride from San Francisco to Los Angeles raising awareness, advocacy, and financial support for community services for those afflicted with HIV, passes through many rural agricultural communities. Through Marina, Salinas, Gonzalez, King City, Bradley, Paso Robles, Santa Maria, or Lompoc, community members bike or walk along the side of the road in dangerous conditions like non-existent shoulders and roadways in need of maintenance or repair. I recently had the honor, privilege, and ability to participate in this bike ride, and along the way, I observed what is so often observed on U.S. streets: when our transportation system prioritizes vehicle speed over all else, other road users fall through the cracks.

It is quite the experience and privilege to ride through the beautiful California countryside, supported by medical and bike tech teams. If I got tired or felt sick from riding, I could stop and get a ride to the next rest stop or hop on a chartered bus to the next overnight camp stop. This unfortunately is not an option for residents and workers alike in these rural communities. Along our route, biking infrastructure was scarce, and other convenient modes of transportation like public transit are often hard to come by. Those of us participating in the bike ride could easily spot rural residents and workers biking for long distances on unprotected paths.

Add the additional pain of high gas prices and scarce and infrequent public transportation options, and many people are left with little option but to walk or bike on hazardous roads with high speed or very large freight vehicles and tractors. For undocumented workers or people living paycheck-to-paycheck who have to show up in-person for work, high gas prices become even more of a barrier and can force people to other modes of travel, even when safe infrastructure is lacking. I observed one woman biking with a shopping cart tied to her bike to carry her goods home.

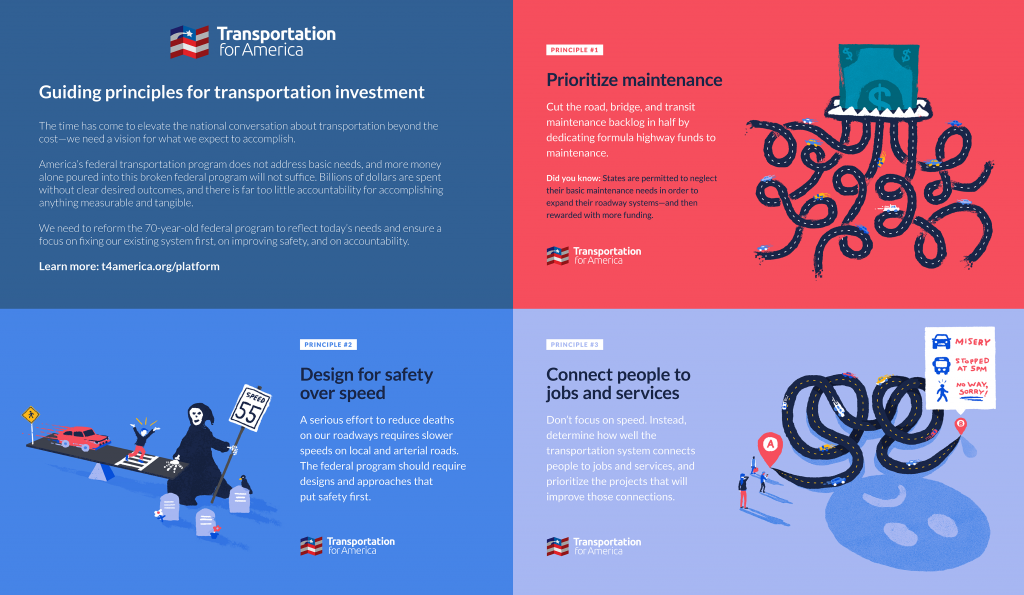

Dangerous rural roadways aren’t specific to California. Over 1 million rural households across the nation have limited mobility options. Leaders in many rural communities are standing up and looking to make changes to improve transportation choices and safety. In California, the city of Salinas has an active Vision Zero program, enacted in 2020, looking to stem the tide on roadway fatalities. Communities like Lompoc are actively looking at policy and funding opportunities to expand their complete streets program. However, as the bulk of their busiest and most dangerous roads are state-owned, these places will have to rely on the state to make sure rural communities receive the investments they need. That will involve emphasizing a better state of repair on roadways, investing in rural transit solutions (including microtransit), not to mention supporting transportation investments, policies, standards, and strategies advancing safety and mobility choice for all roadway users.

Despite the support that cyclists on the AIDS/Lifecycle ride received and the increased safety that often comes while biking in larger numbers, a person was still killed on the final day. Roadway fatalities for pedestrians and cyclists continue to rise, and without making an effort to address the dangerous conditions on our roadways (mainly, the lack of safe infrastructure for road users outside of vehicles), this trend can only be expected to continue. (The 2022 edition of Dangerous by Design, produced by Smart Growth America and the National Complete Streets Coalition, addresses how our streets are designed for vehicles at the expense of all other road users.)

This ride was an experience for the impact it has to its mission, but it also was an experience to “ride in the shoes” of the many residents in these rural communities in Central California, only a sliver of many rural communities in America clamoring for safe, reliable transportation choices for their socioeconomic and health well-being. Often, political leaders assume that all rural residents drive, or only drive, and any investments in other modes of transportation are somehow out of touch with rural needs. But the fight for safer streets and more convenient methods of transportation can’t stop at city limits. That mindset leaves far too many behind.