The Strengthening Mobility and Revolutionizing Transportation (SMART) competitive grant program offers communities funds to apply new technologies to solve their transportation challenges. How smart this program ends up being depends on whether it treats the application of new technology as a tactic, or as a goal in and of itself.

In the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), Congress authorized $1 billion over five years for the Strengthening Mobility and Revolutionizing Transportation (SMART) grant program. This program seeks to fund pilot projects where smart technologies and systems are innovatively used to solve transportation problems by guiding applicants through a two-stage process. In the grant’s first stage, selected applicants will receive funds to do planning and build the partnerships necessary to create a “scaled-up demonstration of the concept” with funds from the grant’s second stage.

The SMART grant is another chapter in an age-old story: looking to technology to solve our transportation challenges. However, in the materials introducing the grant, we can see that there are two perspectives to tell this story from: one from the driver’s seat of a personal vehicle, the other from the sidewalk, bike lane, bus stop, and train station. The first perspective can be found in the Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO), and the second in the illustrative use cases listed on the grant’s website.

From the first point of view, the SMART grant will improve transportation by advancing unproven technologies that ignore the root causes of our safety, state of repair, and emissions difficulties. From the second, this grant can use well-tested solutions that complement efforts to redesign streets and invest in modes of transportation besides cars to improve how we all get around.

Eligible projects vs. illustrative use cases

The eligible projects listed in the NOFO center around technological advancements for automobiles. Based on section titles like “Coordinated Automation,” “Connected Vehicles,” and “Smart Technology Traffic Signals,” you might be forgiven for thinking that the only projects DOT would entertain are those that intend to pave the way for fleets of self-driving vehicles. Thankfully, you would be mistaken.

The illustrative use cases harness technology to improve the experience of pedestrians, cyclists, and transit users. They are broken up by benefits, such as improving safety and reliability, lowering emissions and improving resiliency, and integrating data and sensors into signaling and decision making systems.

For a safer, more reliable transportation system, USDOT suggests giving transit and emergency vehicles priority signals at traffic lights, automating street sweeping vehicles for sidewalks, and implementing active detection technology for railroad crossings. Technology can reduce emissions and enhance resiliency by making room for modes of travel beyond personal vehicles, through actions like improving last-mile delivery and sidewalk accessibility. USDOT also proposes ways technology can help make streets safer and more accessible for all road users. On-demand right-of-way conversions could give pedestrians and cyclists more opportunities to cross the street, and sensors can monitor the quality of signage and crosswalks to help transportation planners make needed changes.

When combined with possible projects to improve equity and access—such as more efficiently delivering reduced-fare transit to those who qualify and adding automated wheelchair securement systems to transit vehicles—these illustrative cases would increase the reliability, frequency, and accessibility of transit trips. Efforts like these could also improve the safety of everybody walking and rolling, by changing both the physical infrastructure of our streets and sidewalks, as well as the signals that guide how we walk, roll, and drive through them.

What could be

These are also by no means a constrictive list of potential applications. By applying the spirit of the illustrative use cases, the categories of eligible projects have a bounty of opportunities for bettering the everyday experiences of pedestrians, cyclists, and transit riders.

People walking and rolling to their destinations could especially benefit from what the USDOT calls “Intelligent, Sensor-Based Infrastructure.” By looking at examples from across the country and the world, we can see how this technology can be used to improve the safety of vulnerable users instead of reasserting the dominance of cars. This type of eligible project could include retractable bollards that support shared streets (check out this Streetsblog article for examples of retractable and moveable bollards in New Orleans, LA and Cambridge, England).

That same category of eligible project might also cover speed governors, a technology that has been available for over a century to limit the speed of cars and will soon be mandatory in some way, shape, or form in all vehicles on the road in the European Union. Furthermore, the requirement that vehicles retrofitted as part of the SMART grant be publicly owned or controlled sets up perfectly those who control public fleets to install such technology in their vehicles. New York City is soon to implement this strategy on thousands of non-emergency vehicles under its control. Combined, these applications of the grant would make walking and biking safer through design of both streets themselves and the vehicles on them.

Transit and rail could also see significant benefits from SMART technologies. “Coordinated Automation” could cover the type of fully automated subway systems—both built from scratch and renovated lines over a century old—that are in operation and under construction around the globe. In addition, this automation requires upgrading signals and sensor systems to ensure that individual trains are more closely connected to one another, a potential application of the “Connected Vehicles” and “Intelligent, Sensor-Based Infrastructure” sections. The “Smart Grid” category could apply to the electrification of rail lines, and given that freight trains carry a significant portion of goods in the United States, their electrification would reduce emissions and the length of the supply chain.

The bottom line: It’s not the tech, it’s how we use it

All of these potential applications are no less innovative technologies than the auto-oriented ones described as eligible activities in the NOFO. In fact, their effective implementation in a wide variety of settings might point to them being more groundbreaking. As reflected in the NOFO’s selection criteria, “revolutionizing transportation” is about not just novelty. It is about proof of concept, scalability, and being appropriately aimed at the particular problem. By these measures, adequately-funded incremental solutions like the signal improvements being installed to more than double speeds on parts of New York City’s subway are exactly the kind of projects applicants should be submitting and USDOT should be encouraging. (For the system’s millions of users per day, speeds are more than doubling in some cases, all at a fraction of the cost it would take to do so for any segment of road.)

And yet, the NOFO’s listed eligible activities reflect the last century’s status quo of transportation policy in the United States. Instead of centering communities’ transportation goals and asking what technologies and other policies could help achieve them, these “technological areas” presuppose that hypothetical fleets of connected, autonomous, battery-electric cars will solve all potential problems.

The effectiveness of the SMART grant will depend on whether or not DOT continues to view cars as the unimpeachable mobility solution without actually asking what problem it is trying to solve. Per the eligible activities listed in the grant’s NOFO, DOT is still not asking this question. But based on the illustrative use cases, DOT knows that achieving tangible benefits from the SMART program won’t come from trying to move more personal vehicles, but using technology to improve the mobility of all road users, especially people outside of a car.

Because this is the first year that the grant is being administered, and USDOT will require Stage 2 applicants to be recipients of Stage 1 grants, only Stage 1 grants will be accepted this year. Applications for these planning, prototyping, and partnership-building grants are due by 5 p.m. on November 18, 2022. Their tentative maximum size is $2,000,000, depending on the number and quality of applications submitted, with up to $100,000,000 and no less than $98,000,000 available to distribute.

Transportation for America members have access to exclusive resources that provide further detail on this topic. To view memos and other members-only resources, visit the Member Hub located at t4america.org/members. (Search “Member Hub” in your inbox for the password, or new members can reach out to chris.rall@t4america.org for login details.) Learn more about membership at t4america.org/membership.

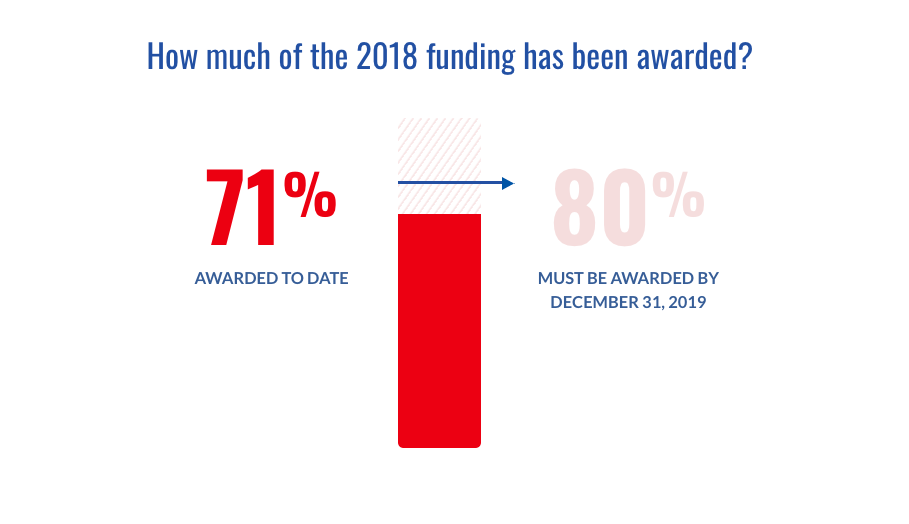

With federal employees at the Federal Transit Administration furloughed during the recent record-length shutdown, transit funding wasn’t being distributed and grant/loan programs ground to a halt. New projects were further delayed and transit providers were faced with hard choices about service cuts, showing the vital importance of federal funding for transit.

With federal employees at the Federal Transit Administration furloughed during the recent record-length shutdown, transit funding wasn’t being distributed and grant/loan programs ground to a halt. New projects were further delayed and transit providers were faced with hard choices about service cuts, showing the vital importance of federal funding for transit.