Money from the finalized $1.2 trillion infrastructure deal is already flowing out to states and metro areas who are plugging it right into projects both already underway and on the horizon. After covering six things the administration should do immediately to maximize this mammoth infusion of unexpected cash, here’s a longer look at some of the law’s incremental or notable successes, with the aim of equipping the administration and advocates alike to steer this money toward the best possible outcomes.

This post is part of T4America’s suite of materials explaining the 2021 $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which governs all federal transportation policy and funding through 2026. What do you need to know about the new infrastructure law? We know that federal transportation policy can be intimidating and confusing. Our hub for the new law will walk you through it, from the basics all the way to more complex details.

Passenger rail

If you’re looking for good news in the infrastructure bill, passenger rail probably represents the most encouraging and exciting inclusion in the bill. After being woefully neglected over the past 40 years, passenger rail is one of the biggest winners, receiving a historic investment that totals just north of $100 billion over five years. (All of which is thanks to impressive bipartisan work by the Senate Commerce Committee earlier this summer—read our much more detailed take on all the passenger rail provisions here.)

This will provide significant opportunities to reshape American passenger rail in a transformative way. With the record investment, there is ample opportunity to improve safety and state of repair for existing rail infrastructure, make existing service more reliable, and support new, expanded passenger rail service. Communities near rail and lacking in intercity mobility options could connect their community with affordable intercity mobility and integrate passenger rail service with first- and last-mile community connections.

But these improvements are not going to happen automatically nor will they happen easily. The Biden administration, the Federal Railroad Administration, Amtrak and others will have to be very aggressive in ushering this money out the door and supporting state and local plans for those improvements to see the projects that have been promised or mentioned in breathless news coverage come to pass. If the administration fails on this count, this could turn out just like the 2009 Recovery Act, where money sat idle or was even declined by governors. On top of that, freight railroads will be opposed to the improvements in some places, just like they’ve fought or negotiated in bad faith against the publicly and politically popular plan to restore passenger rail along the Gulf Coast.

Additionally, Amtrak’s mission and governing structure have been adjusted to bring a greater focus on expanding and improving the national network. For the majority of Amtrak’s existence, the mission of passenger rail service was to justify investments with performance and operate to make a profit, no matter the cost to user experience, and no matter that nearly every other transportation mode fails to turn a profit. This hampered innovation and opportunity to build and retain rail ridership. Small but significant changes in the infrastructure bill reorient Amtrak’s mission towards the value of the customer and the importance of connecting those customers across urban and rural communities.

While the bill lays out goals for an Amtrak Board of Directors that better represents a diversity of perspectives and communities across the Amtrak system, as we noted last week, those slots need to be filled immediately if the administration is serious about improving passenger rail service and taking advantage of the funding and this historic opportunity.

By reinvigorating passenger rail infrastructure and user experience, this bill could lay the groundwork for other future advancements, including high-speed rail.

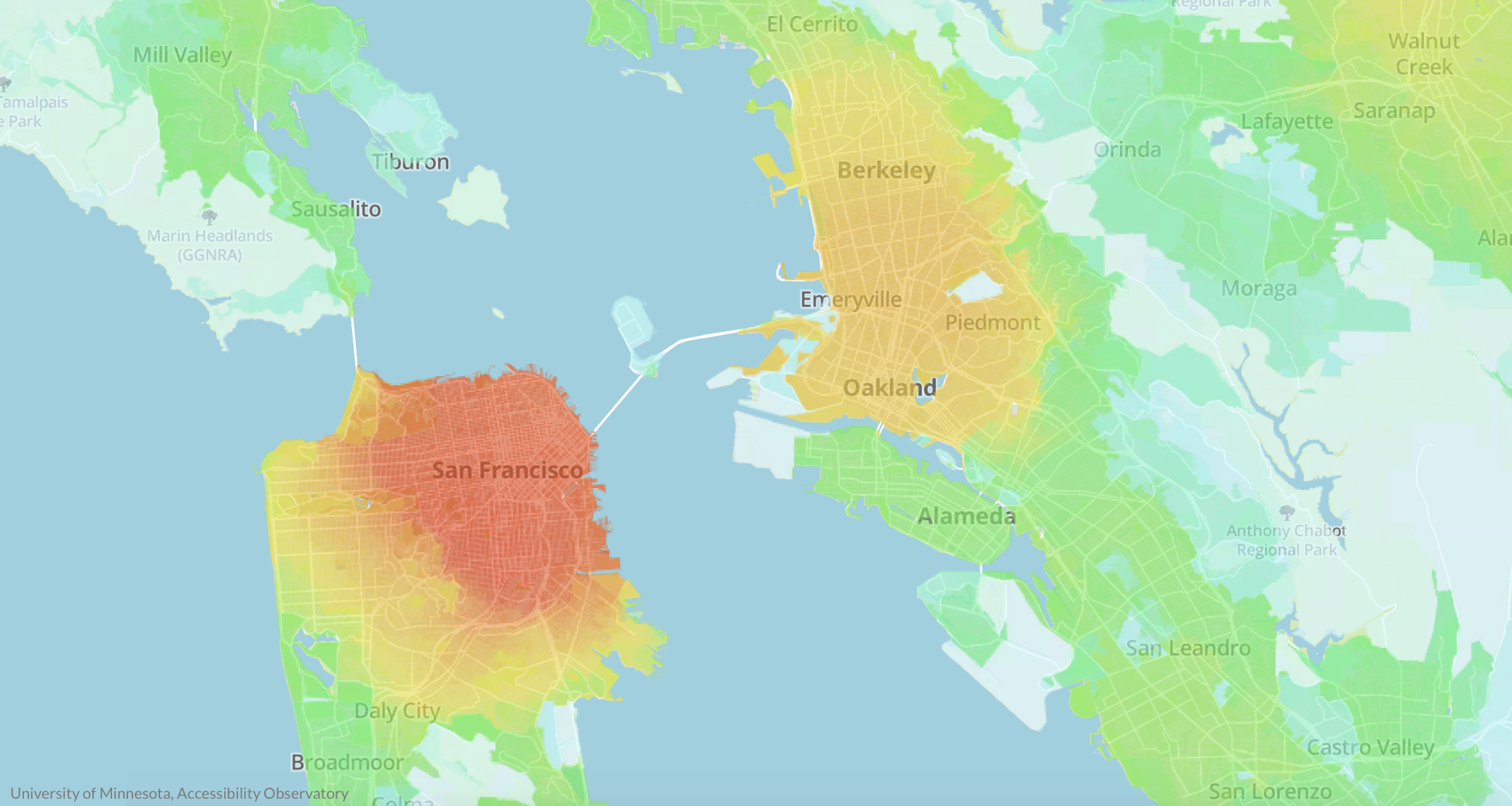

Connecting people to jobs and destinations

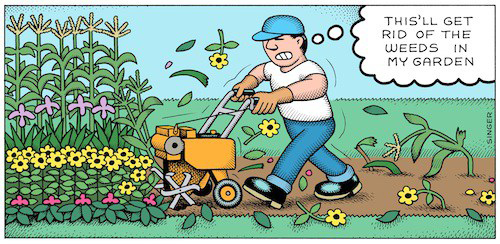

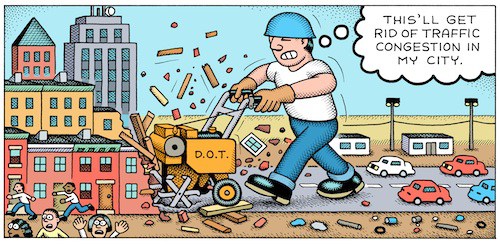

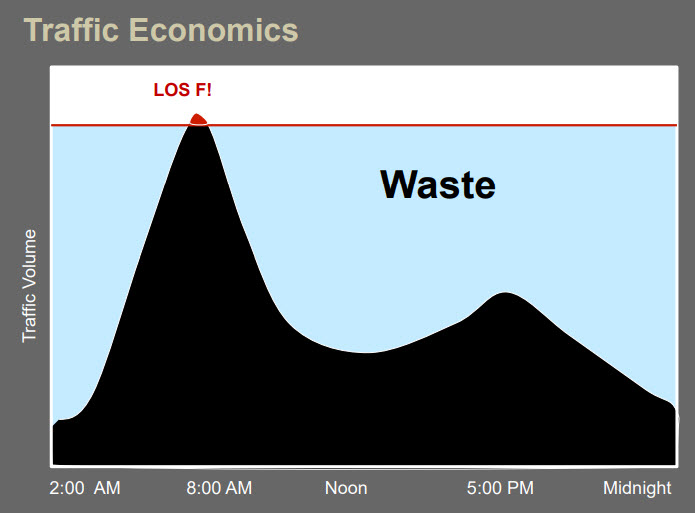

As we’ve noted, the bill pours the lion’s share of the funds into the same old highway programs with few substantial changes. And states are already responding to their hard-won flexibility and historic amounts of cash by supercharging previously planned or ill-conceived projects. But there are some notable ways the bill recalibrates the highway program for the long run.

First, a portion of every state’s funding will go to new programs aimed at reducing carbon emissions, improving transportation system resiliency, and congestion relief, in addition to existing money devoted to Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) dollars. States and metro areas must also now dedicate a portion of their planning money towards Complete Streets planning and implementation. (2.5 percent of each state’s State Planning Research dollars and 2.5 percent of their metropolitan planning dollars.) This money will be dwarfed by the hundreds of billions going into streets and roads being designed the same old way, but this is an incremental step toward elevating active transportation and livable streets within the transportation program.

Within the largest pot of funding that states and metro areas control (the Surface Transportation Block Grant program), the amount set aside for smaller but vital transportation projects like bikeways, new sidewalks, safe routes to school, and micromobility was increased from 1.5 percent up to 10 percent. This bill also lets local municipalities control more of this funding directly by increasing the share of that 10 percent that they directly control from 50 up to 59 percent

Lastly, while the $1 billion Reconnecting Communities program will be overpowered by hundreds of billions in highway funds perpetuating the very problem this program aims to solve, its inclusion is an important step toward repairing the damage of past highway projects and is worth celebrating. For the first time, Congress is acknowledging the racist and damaging history of highway building, laying the groundwork for future efforts and also providing a way for advocates to spotlight how some of the worst excesses of the past are still going on today in many urban areas. But devoting any federal dollars to tearing down divisive infrastructure plus the means to stitch communities together again is a vital step on the path toward reorienting the highway program to serving people and communities with the transportation system.

Transit

Most of the headlines and coverage about transit focused on the fact that it will receive historic levels of investment over the next five years from the infrastructure deal. That’s certainly good news, but that also glosses over some important shortcomings.

First off, unlike the Senate Commerce Committee did with passenger rail, the Senate Banking Committee never actually drafted a transit title to incorporate into the infrastructure bill. This preserved the transit policy status quo in amber for the next five years. Secondly, while the House’s superior INVEST Act proposal focused on trying to maximize transit service, frequency, and access, this bill failed to fix the current priority of keeping costs down no matter the effects on people when it comes to service, ridership, and access to transit. T4America is still looking to Congress to redress that wrong within the still-in-progress budget reconciliation bill (the Build Back Better Act), ensuring that public transportation, a fundamental backbone in our communities and a lifeline towards affordable housing opportunities, is properly funded.

Thirdly, while the $39 billion is a historic amount for transit and many excellent projects will be built because of it, this amount should have been higher. $10 billion was cut from the original infrastructure deal’s framework agreement with the White House back in June.

While we weren’t anticipating the Senate increasing the share for transit, the infrastructure bill did maintain the historic practice of devoting at least 20 percent towards public transportation and did not decrease it. On a positive note, the bill emphasized improving the nation’s transit state of good repair, plus improving transit accessibility via a grant program to retrofit transit stations for mobility and accessibility.

Environmental stewardship and climate adaptation

Although the infrastructure bill continues to heavily fund conventional highway and road expansions, digging us into an ever deeper hole of traffic congestion and greenhouse gas emissions, it is also the federal government’s biggest investment yet in climate adaptation and protection and recognizes the severity of the impacts of climate change which are already being experienced across America.

The new PROTECT program dedicates $7.3 billion (~2.9 percent of each state’s share of all highway funds) and $1.4 billion in competitive grants to shore up and improve the resilience of the transportation network, including highways, public transportation, rail, ports, and natural barrier infrastructure. Knowing where climate- and weather-related events are likely to be worse is a vital first step, and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) will invest $492 million in flood mapping and water modeling which could inform future infrastructure planning and investment.

The existing Alternative Fuels program is expanded and recalibrated to focus more, though not exclusively, on zero-emission vehicles and related infrastructure. A new Carbon Reduction program will dedicate ~2.5 percent of each state’s share of highway funds (~$6.4 billion total) to support active transportation, public transit, congestion pricing, and other strategies to reduce carbon emissions. (Although the core highway program will continue making emissions worse.)

All of this represents a positive first step in federal recognition of the severity of the impacts of climate change, but it is still not scaled to the level of risk that we face, though we applaud Congress for taking a bipartisan step on climate change and we hope to see more.

Safety

When it comes to safety, a new federal safety program, even a large one, is not what we need. The entire $300+ billion transportation program should be a safety program, with safety for all users as the highest and ultimate consideration in every single case on every single project. A transportation system that cannot safely move people from A to B should be viewed as a failure, regardless of whatever other benefits it brings.

With that backdrop in mind, there are key safety provisions that ensure a fairer shake for vulnerable road users. If injuries to and deaths of people walking, biking or using assistive devices exceed 15 percent of a state’s total traffic injuries and fatalities, then that state must dedicate at least 15 percent of their Highway Safety Improvement Program dollars towards proven strategies to make those people safer and lower that share. This helps put some teeth into highway safety dollars to target investments where they are critically needed, versus typical lip-service and disingenuous investments sold as safety projects that are really about increasing capacity, speed, or other goals.

The new Safe Streets and Roads for All program is a competitive grant program allowing applicants to seek funding to better plan and implement Vision Zero strategies in their communities and regions. Once deemed a niche concept, the Vision Zero safety framework has gained some prominence. For it to go mainstream, it will need to be fundamental to all highway spending.

Looking ahead

Though this bill leaves much to be desired, there are still some notable changes that will start to shape the direction of state, regional, and local transportation programs. The key will be how they are used. In the coming weeks, T4America will highlight key opportunities to better administer, deliver, and shape the US transportation program for generations to come.

Transportation is fundamentally about connecting people, but America’s transportation system focuses on moving cars instead. Madlyn McAuilffe from the

Transportation is fundamentally about connecting people, but America’s transportation system focuses on moving cars instead. Madlyn McAuilffe from the