People disparage rural areas with the term “flyover country,” but our federal transportation program currently treats rural areas even worse—as “driveover” country. If Congress adopts Transportation for America’s three new policy principles, transportation investments could truly help rural areas prosper.

A focus on speed rather than safety and access would result in telling Erwin, TN that they need to widen this road and get rid of the crosswalks. Federal transportation policy doesn’t work for rural America.

This week, we released our three guiding principles and three outcomes we expect from any new investment in transportation. These ideas will start to fix our broken system and improve safety and access to opportunity for all—including rural areas.

When I was a small town mayor in Mississippi, I fought transportation policy that treated our town like it was “driveover” or “drive-through” country. Our transportation program makes it far easier for rural communities to build highways—which residents can use to drive far away for jobs, schools, education, and other services—than it does to help rural places invest in their vital town centers.

What the federal government doesn’t realize about rural areas is that they are not comprised of empty towns and open fields that need to be driven through as fast as possible. In reality, rural areas are dotted with countless walkable town and community centers.

In some rural areas, these walkable places are the center of commerce and activity for that town. But unfortunately, in too many rural areas, thanks to federal transportation policy that prioritizes new highway construction and roads designed primarily for speed—no matter their context—these once-thriving walkable places have been hollowed out, with jobs and services now located far away.

Our three principles would improve life in rural areas by finally treating rural areas as places to be, not places to drive away from.

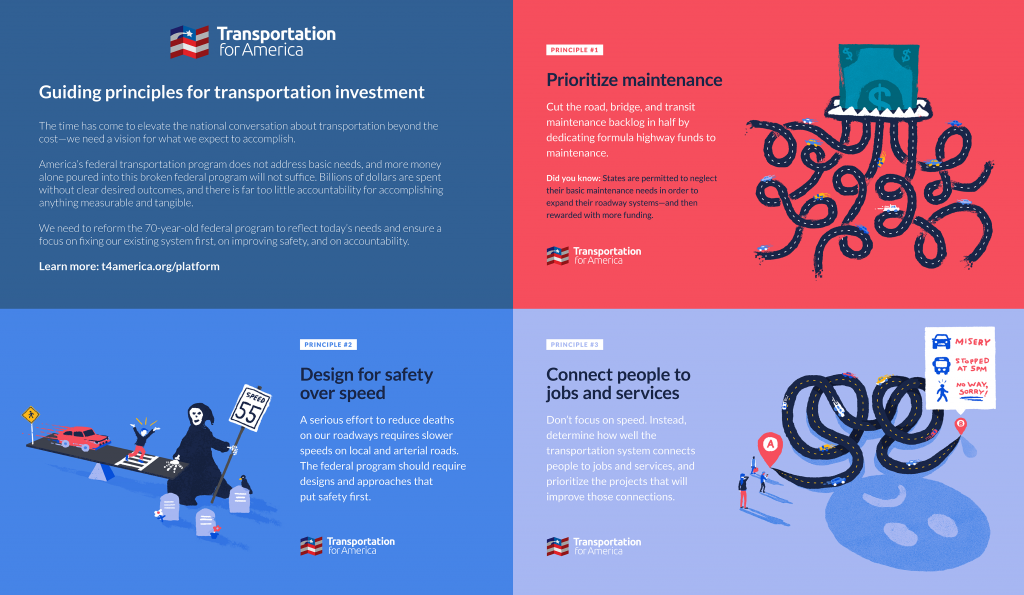

Maintenance

When I was mayor of Meridian, Mississippi, the state had 12,000 bridges that were structurally deficient. This hammers rural places especially hard. If a bridge needs to be shut down—or even worse, collapses—some areas might lose their only quick connection, and then people can’t get to their doctors, produce can’t get to market, and students can’t get to the community college. Without these bridges, rural areas are isolated.

Unfortunately, the current federal transportation law allows states to kick the proverbial maintenance can down the crumbling road. Many times, states use this money to build new infrastructure while letting their existing assets crumble. (Something Mississippi did for many years, though their state DOT has recently made a drastic about-face, a story Mississippi DOT Commissioner Dick Hall outlined in our press briefing for Repair Priorities.)

That’s why our third principle, “prioritize maintenance,” would require states to fix these structurally deficient bridges before building new roads or bridges they can’t afford to maintain. It would ensure that rural places will not be stranded.

Speed

Oftentimes, the main street of a rural community is a state highway that passes right through the heart of downtown. Because of federal design standards and a focus on the speed of travel above all other priorities, the main street is unsafe and unattractive for people to bike and walk in a very small urban grid, and it’s terrible for the local economy.

Main streets shouldn’t be highways that get people through communities. They should be arteries that bring people in. Walkable main streets in rural areas can and should be a huge driver of economic development for a small town, generating a large, prosperous tax base in a very small area.

In West Jefferson, NC, by prioritizing safety and access over speed, 10 new businesses opened along Jefferson Avenue—adding 55 new jobs— and the number of visitors to downtown increased by 14 percent. Four-way stop signs, crosswalks, and upgraded sidewalks were added—anathema to our broken system where speed is the top priority.

That’s why our second principle, “design for safety over speed,” would prioritize designing main streets to serve their intended functions, not as unsafe highways for speeding traffic right through a town center. Any road embedded in an urban grid where people walk and bike, where businesses or homes are located, and where an outside portion of the county’s economic base is located—like in countless rural downtowns—should never be designed for deadly highway speeds.

Access

When state DOTs build new transportation infrastructure, they might share how wide the shoulders are going to be or brag about how much a new road will speed traffic up, but they never tell the public how transportation projects will make their lives better. That’s because improving people’s access to destinations is not how we measure success. We “measure” success by how fast vehicles are traveling, with no measurement of what destinations you can actually reach.

Bentonville, AR’s downtown is a place to bring people to and connect to nearby neighborhoods, not to speed cars through on their way somewhere else.

Put another way, traveling for 15 minutes at 40 mph and going 10 miles is preferred to traveling for 15 minutes at 20 mph and only going five miles, for absolutely no good reason at all. If every daily need in a small town is a 15-minute drive at 20 mph, what’s the point of building a brand new road on the edge of town that can speed you along at 40 or 50 mph?

This focus on speed results in orienting every transportation project—whether in a big city or a small town—around the goal of moving cars as fast as possible, telling everyone who wants to live in vibrant small towns that the needs of their automobiles come first.

Rural areas also have higher percentages of elderly, low income, and disabled people, presenting greater challenges to connectivity and transportation infrastructure. But when access is truly prioritized—meaning that transportation projects are chosen by how they improve people’s lives by improving their access to daily destinations, no matter how they travel—everybody benefits.

That’s why our third principle is “connect people to jobs and services.” Improving access means that instead of making a road wider for cars to drive just a little bit faster, a jurisdiction might instead build a crosswalk in a rural downtown, or add a new road to the street grid, because those investments would do far more to better connect more people to more destinations.

The goal of connecting people to the things they need—which is fundamental to the purpose of transportation—is currently missing from the federal transportation program, and this affects rural areas just like it does any big coastal city

By making access the goal, designing local streets for safer, slower speeds, and ensuring that maintenance is more than just talking point politicians use to get more money to spend, we can improve the lives of people all across the country.

America’s rural areas are filled with wonderful small towns and vibrant communities. It’s time for our federal transportation policy to build them up rather than pave them over.

Click on any image below to learn more about our brand new principles or download a sharable card

How could a new transportation bill revitalize rural and small-town America? That was the focus of a Senate Democratic Steering Committee briefing on “Issues and Innovations for Small Towns and Rural Communities” in the Capitol Visitors Center last Friday.

How could a new transportation bill revitalize rural and small-town America? That was the focus of a Senate Democratic Steering Committee briefing on “Issues and Innovations for Small Towns and Rural Communities” in the Capitol Visitors Center last Friday.