Under President Trump, USDOT has hijacked the TIGER/BUILD competitive grant program, taking it far from its intended function. After a decade of experience with the program there are a number of simple steps that lawmakers could take to get it back on track and even improve it.

This is the second post in a series about the BUILD program. Learn more about the Trump administration’s dramatic changes to the BUILD program in the first post. Read the third post or download the full analysis.

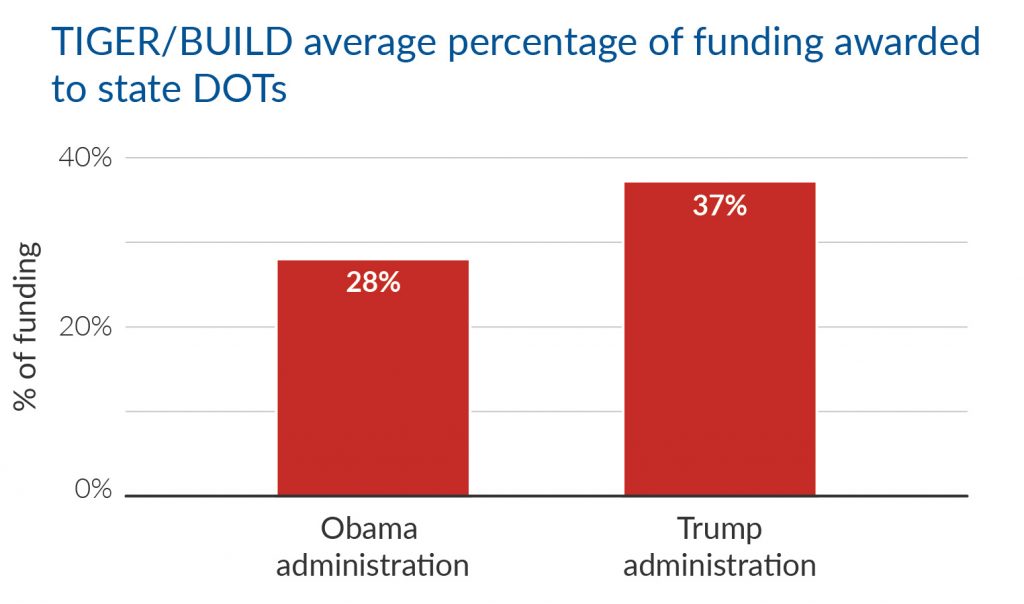

The BUILD program’s greatest strengths lie in its differences from other federal transportation funding programs, which should be reinforced, rather than diminished in order to award funding to the same kind of projects as core federal transportation programs. BUILD has the potential to continue to fund great projects only if Congress stays diligent and ensures that USDOT executes the program as intended. BUILD is not a roads program, it is not a rural funding program, and it is not another vehicle for funneling more money without any accountability to state DOTs.

Recommendations to improve BUILD

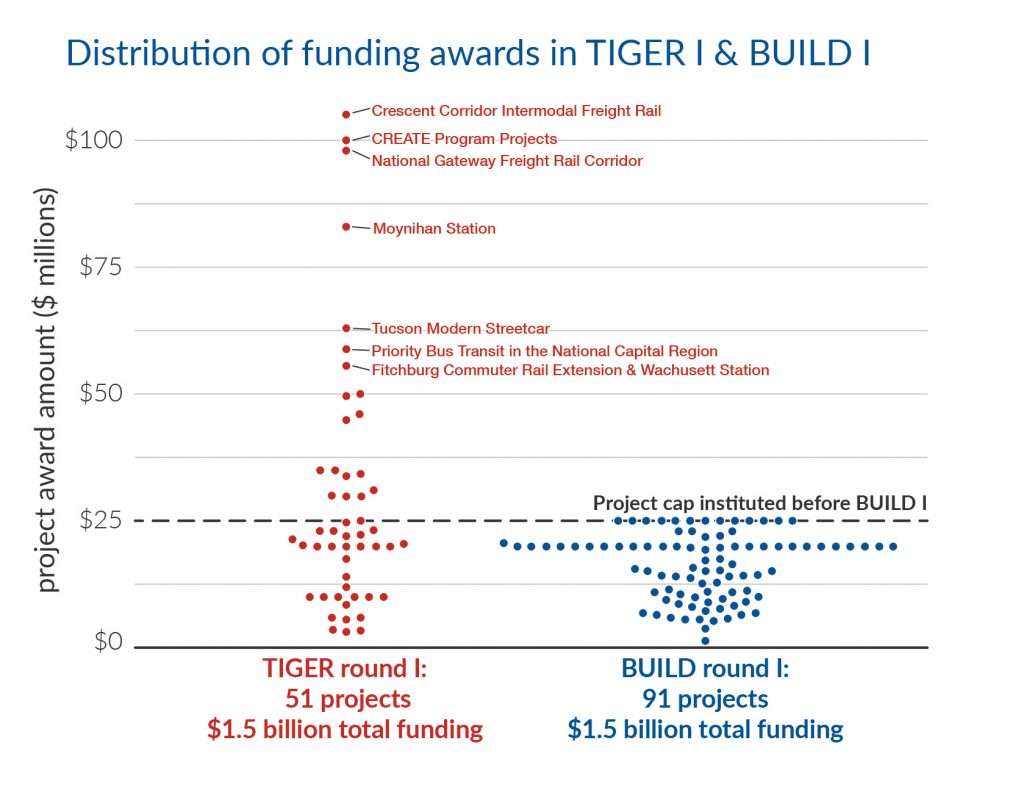

1. Eliminate the $25 million cap on awards.

Even though the program is now larger (average of $967 million during the Trump administration) than it was in most years of the Obama administration ($596 million per year on average), the most recent appropriations bill included a $25 million cap on BUILD grant awards. This has the unintended consequence of making it more difficult to advance innovative, multimodal, and far more transformative or nationally significant projects. For such projects, $25 million simply isn’t enough.1

The maximum award of $25 million was an informal practice established by USDOT early on when the program was funded at substantially lower levels, in order to help them equitably distribute a small amount of funds across the country, as mandated by Congress. However, with Congress providing larger amounts of funding for BUILD, this unnecessary cap serves only to limit the program’s ability to support larger projects that also bring more benefits.

2. Award planning grants, particularly for transit-oriented development and transit projects.

While recent appropriations bills have made planning grants eligible for funding, no such grants have been awarded. Many local communities desire investments in transit, transit-oriented development, and other multimodal infrastructure, but lack the resources or expertise to adequately plan for such investments.

Congress authorized planning grants within TIGER/BUILD four times—in 2010, 2014, 2018, and again in 2019, and USDOT awarded a combined 64 planning grants in 2010 and 2014. These grants helped local communities advance projects that were ultimately funded by a subsequent TIGER/BUILD construction grant, or other sources. For example, the 2014 funding of the San Francisco Bay Area Core Capacity Transit Study helped enable the advancement of the Transbay Corridor Core Capacity project in the federal transit capital program. In Indiana, another 2014 planning grant helped locals to advance the Red Line BRT project which also successfully received funds from the transit capital program and is currently under construction.

Innovative projects can struggle to get off the ground because transportation agencies can be hesitant to spend money on planning a project if there isn’t going to be any funding available to build it. But a program like BUILD can’t cover the capital costs of a project if no basic planning has been done. That’s why these BUILD planning funds are so important. USDOT should use its authority to make planning awards where appropriate, and Congress should also encourage USDOT to use this authority as well.

3. Strengthen requirements for modal parity.

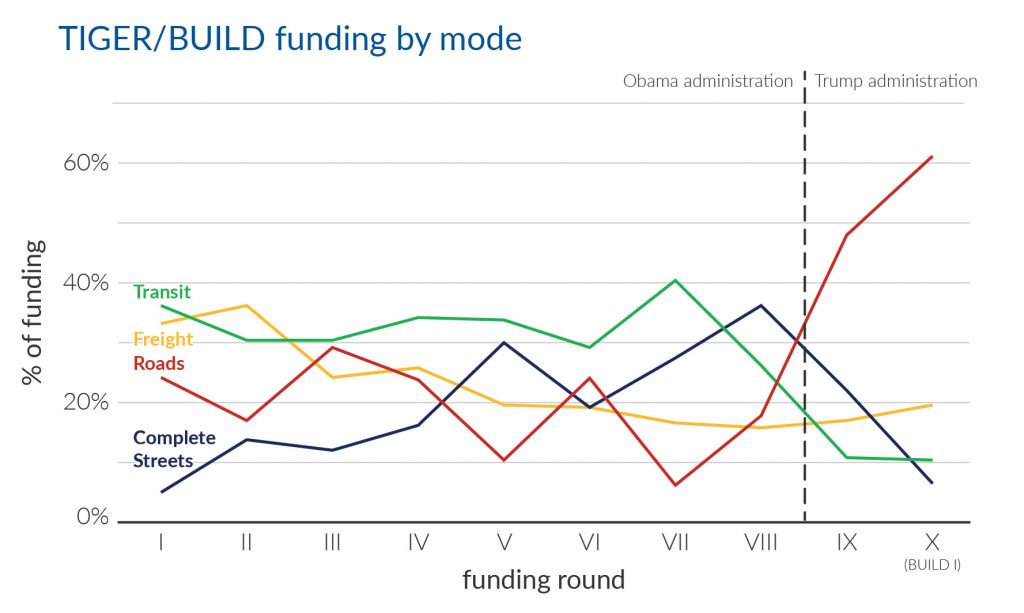

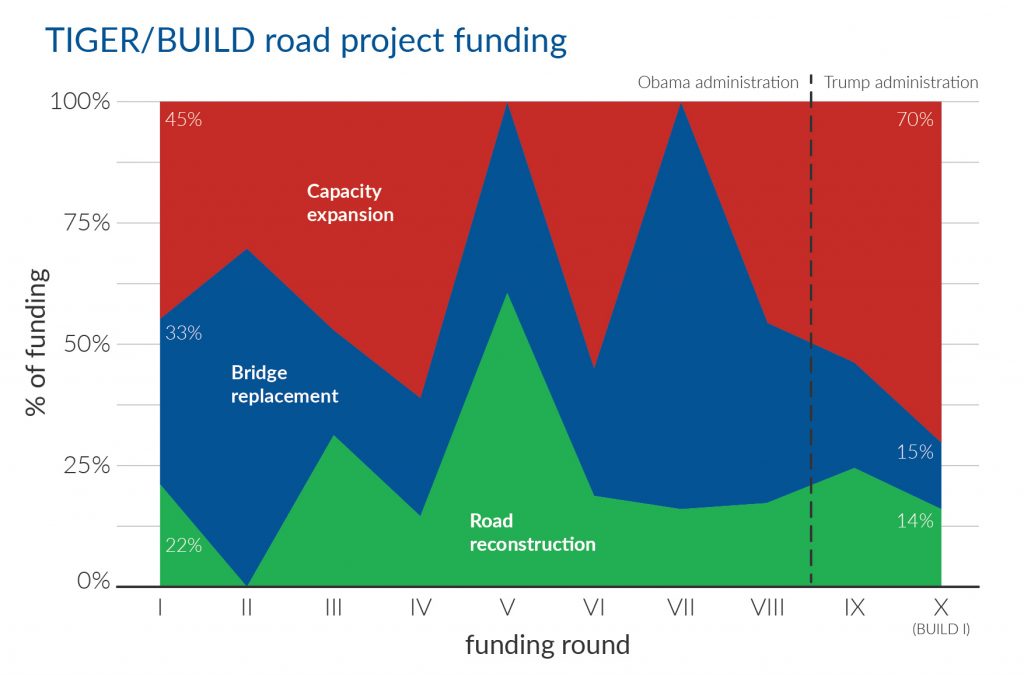

This administration has made a dramatic shift to use the BUILD program to fund traditional road projects which can already be easily funded without restriction through a variety of conventional federal programs. This misuse of the program should prompt Congress to strengthen requirements to allocate funding to multimodal projects, including transit and passenger rail. Alternatively, Congress should consider dedicating more trust fund money to these modes if BUILD funding is not going to be made available to them.

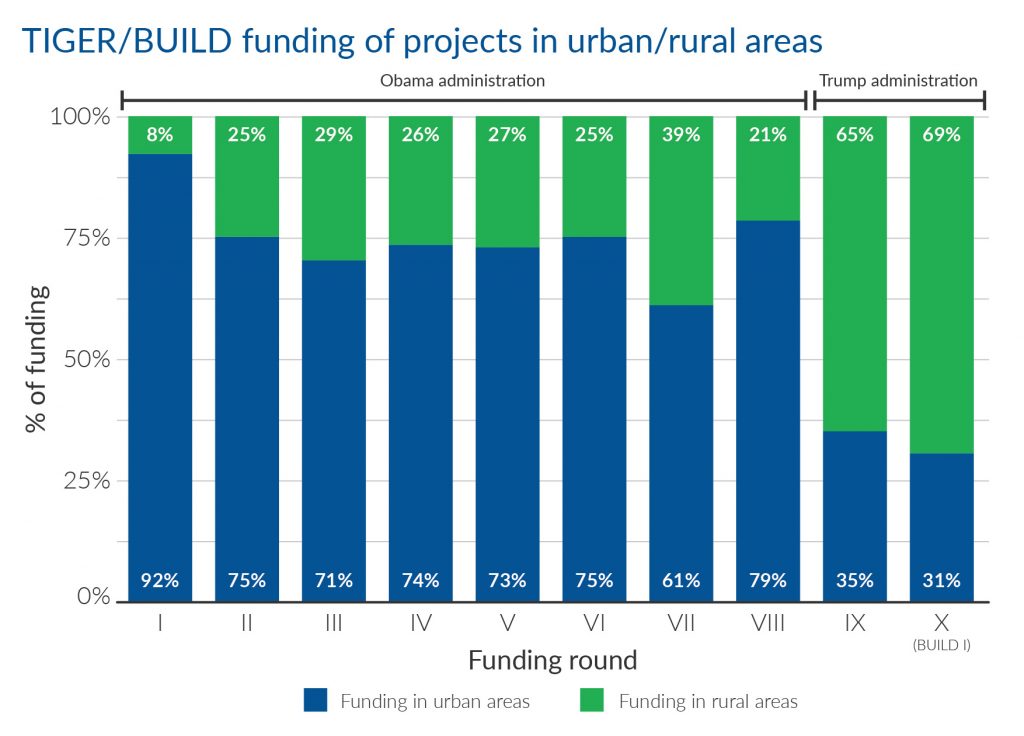

4. Require a more equitable urban/rural funding split.

Congress should make clear that a more equitable urban-rural split is appropriate and provide more clear guidance to USDOT about how they are expected to consider the needs of both urban and rural America. Currently, USDOT awards grants to either urban or rural projects, with a set-aside for rural projects. This creates a false choice between the two.

For example, the CREATE project in Illinois, which will relieve freight rail bottlenecks and allow goods to more easily move to market through the country, is considered an “urban” project. This, despite the fact that about 25 percent of rail traffic in the United States travels through the Chicago region, and farmers and businesses from rural areas will benefit from reduced freight congestion. The benefits of an urban or rural project are not limited only to the jurisdiction where construction will take place. USDOT should consider the full impact of a project, on both urban and rural areas when determining a projects classification.

5. Authorize the BUILD program in long-term transportation policy.

The TIGER/BUILD program stands out as the only major federal transportation program that has not been authorized by the FAST Act and previous authorizing legislation, leaving its fate in limbo each year. While Congress has continued to fund it through the annual appropriations process, authorizing the program over multiple years at $1.5 billion annually would provide some certainty to potential applicants and allow Congress to establish more policy guardrails to ensure it operates as intended.

Many of these recommendations currently have support in Congress. In particular, 20 members of Congress recently signed a letter led by Representative Mark DeSaulnier (CA-11) to USDOT expressing concern about how they have been facilitating the BUILD program. That letter endorsed some of these recommendations.

The BUILD program has long been a bipartisan winner because it is so flexible. It gives communities a unique opportunity (and in some cases the only opportunity) to win direct federal assistance for a priority transportation project that would otherwise be hard or impossible to fund. However, the dramatic shift in focus underway at USDOT seriously undermines the utility of the program by directing dollars away from innovative, multimodal projects and instead heavily favoring conventional road projects that can already be more easily funded.

The recommendations above will help Congress keep TIGER roaring (or BUILD building) as the program enters its second decade.

Up next, lessons from the past 10 years of TIGER/BUILD that should inform federal transportation policy at large. Read the final post or download the full analysis.

Sean Doyle was the primary author of this report for Transportation for America, with contributions from Beth Osborne, Scott Goldstein, Jordan Chafetz, and Stephen Lee Davis.

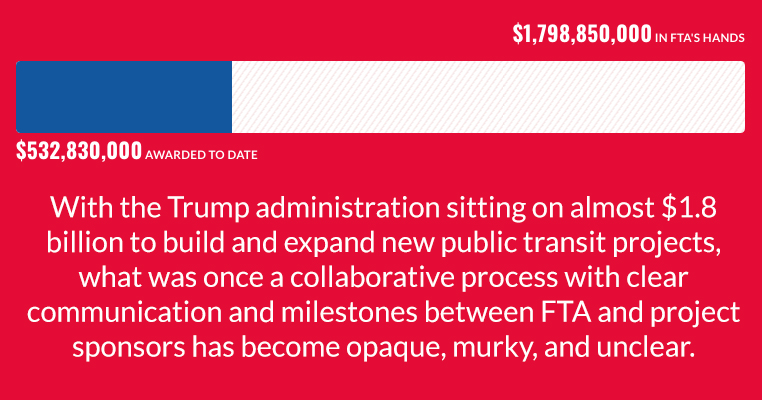

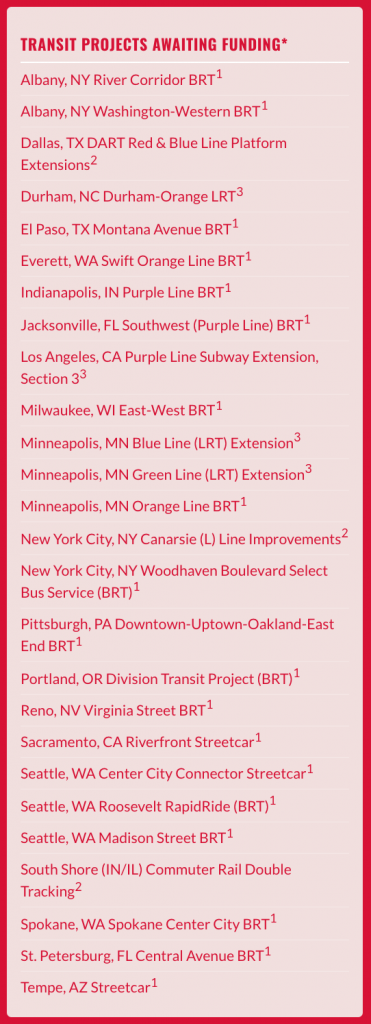

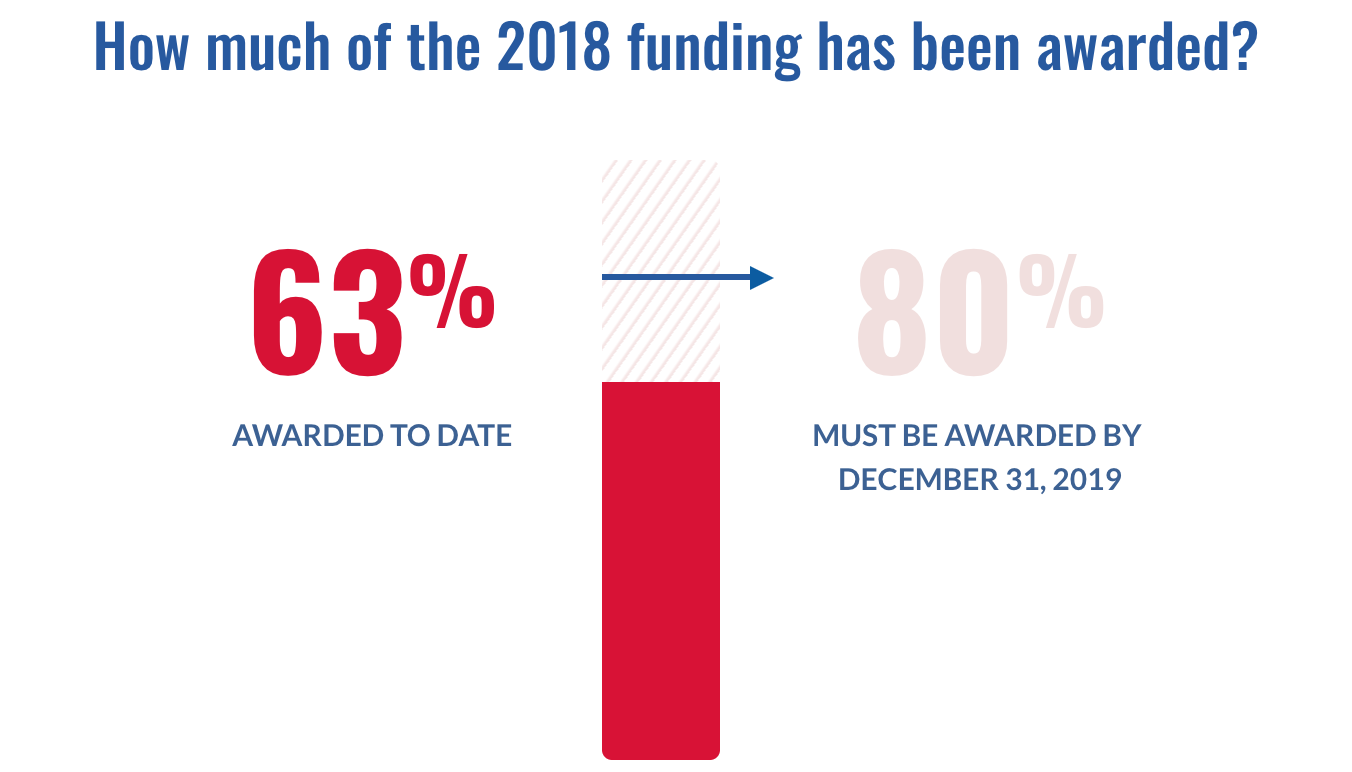

With federal employees at the Federal Transit Administration furloughed during the recent record-length shutdown, transit funding wasn’t being distributed and grant/loan programs ground to a halt. New projects were further delayed and transit providers were faced with hard choices about service cuts, showing the vital importance of federal funding for transit.

With federal employees at the Federal Transit Administration furloughed during the recent record-length shutdown, transit funding wasn’t being distributed and grant/loan programs ground to a halt. New projects were further delayed and transit providers were faced with hard choices about service cuts, showing the vital importance of federal funding for transit.