Nearly every bus transit rider starts and ends their trip with a walk, and decisions made to prioritize vehicle speed over safety often have significant impacts on transit. This excerpt from the new book Better Buses, Better Cities helps explain how better bus transit and prioritizing safety over speed are intrinsically related.

The content that follows is an excerpt from “Better Buses, Better Cities: How to Plan, Run, and Win the Fight for Effective Transit” by Steven Higashide, published by Island Press. Steven is a former colleague of ours at T4America as an outreach associate based in New York a few years ago before moving on to the Tri-State Transportation Campaign and then to TransitCenter, where he today serves as the research director. We are proud to see his book in print and are thankful to him and Island Press for letting us share this long excerpt from Chapter 4 entitled MAKE THE BUS WALKABLE AND DIGNIFIED, sourced from pages 59–61 and 74-75. – Stephen Lee Davis, T4America.

The content that follows is an excerpt from “Better Buses, Better Cities: How to Plan, Run, and Win the Fight for Effective Transit” by Steven Higashide, published by Island Press. Steven is a former colleague of ours at T4America as an outreach associate based in New York a few years ago before moving on to the Tri-State Transportation Campaign and then to TransitCenter, where he today serves as the research director. We are proud to see his book in print and are thankful to him and Island Press for letting us share this long excerpt from Chapter 4 entitled MAKE THE BUS WALKABLE AND DIGNIFIED, sourced from pages 59–61 and 74-75. – Stephen Lee Davis, T4America.

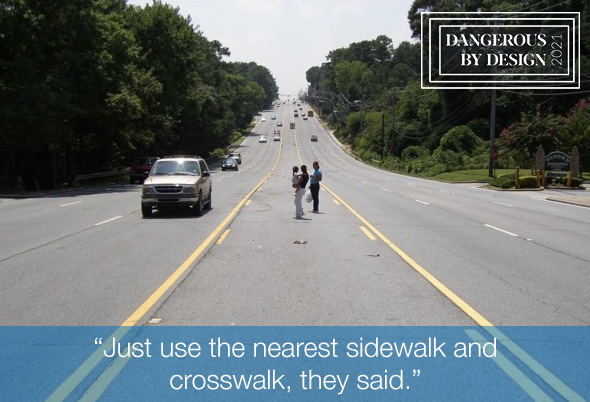

On a Saturday afternoon in April 2010, Raquel Nelson, her 4-year-old son A.J., and her two other children (aged 2 and 9 years) stepped off the bus across the street from their apartment in Marietta, Georgia. It had been a good but long day. Raquel and her children had celebrated a birthday with family and pizza. To get home, they took their first bus from the pizza restaurant to a transit center, where they missed their connecting bus and had to wait more than an hour for the next one.

Home was across a five-lane, divided road. And so, together with several other people who had been on the bus, the Nelson family crossed halfway across the street to wait in the median. As Raquel stopped to gauge traffic, one of the other adults in the group decided to start walking. Raquel’s son A.J. broke free from her grip to follow, and Raquel hurried to catch up.

A.J. was killed moments later, by Jerry Guy, who was behind the wheel of a van despite having “three or four beers” in his system.

Raquel and her 2-year-old daughter were also struck and injured. And yet that was only the beginning of her ordeal.

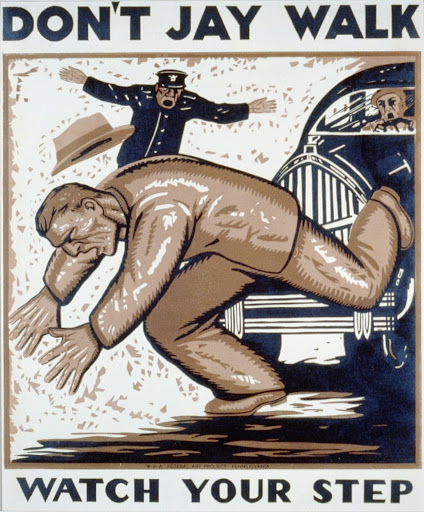

County prosecutors charged Raquel with vehicular homicide, which carried a potential sentence of 3 years in prison. A jury convicted her, and she was sentenced to 12 months’ probation with the option of a retrial, which she chose. Her case wound through the courts for 2 more years before Raquel agreed to plead guilty to a single charge of jaywalking.

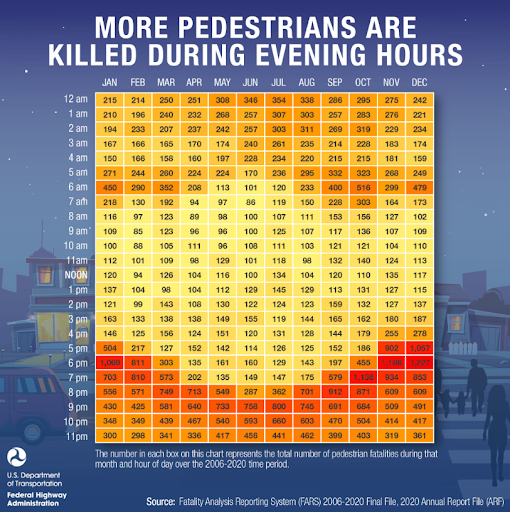

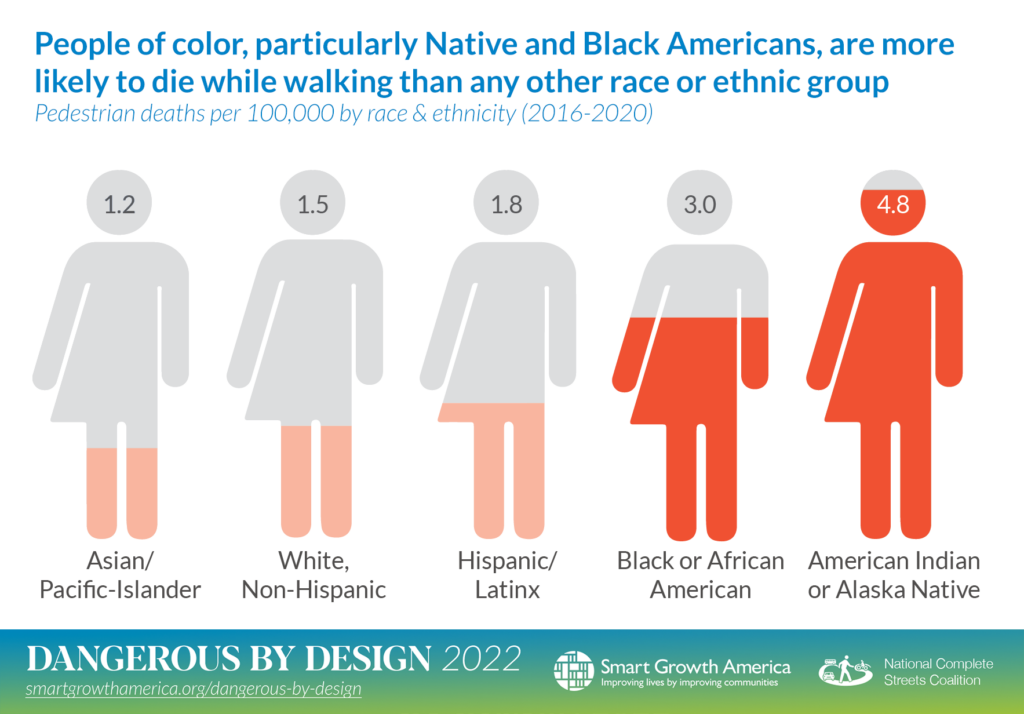

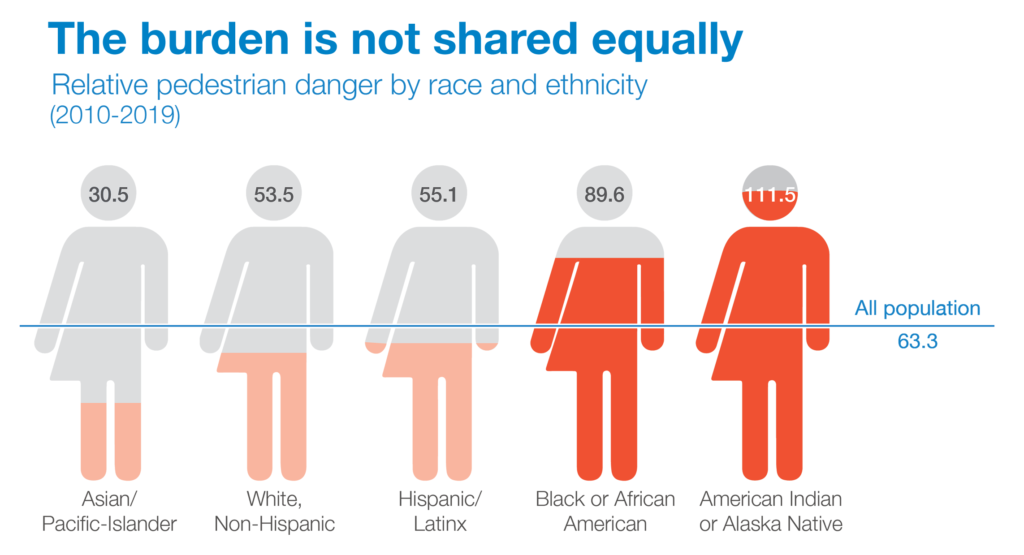

Raquel Nelson’s case made national news. But the loss she and her family experienced is replicated in nearly every city on wide “arterial” roads that encourage high speeds. In the City of Los Angeles, for example, 6 percent of streets are responsible for 65 percent of traffic deaths and injuries. When mapped, pedestrian deaths line up on these roads like dominoes.

Because they tend to have important destinations on them, arterial roads also tend to carry the most bus riders. But the tie between transit and walkability goes beyond pedestrian safety. Nearly all transit riders are pedestrians at some point during their trip. In Los Angeles, for example, 84 percent of bus riders get to their bus stop on foot.

The pedestrian experience is the transit experience, then. A bus rider may appreciate frequent and fast service but still be dissatisfied with her trip if she has to trudge through mud on the way to the bus stop, cross the street with her head on a swivel, and wait in the rain with no shelter. Someone who uses a wheelchair may be unable to use the bus at all if there are no sidewalks leading to the stop.

Poor walkability is corrosive to bus ridership and makes it harder to improve transit service. In Staten Island, New York City, transit planners had to make major adjustments to a redesign of the borough’s express buses after riders complained that the changes forced them to walk in the street or on lawns.

Although Austin’s bus network redesign has generally been considered a success, it ran into the same problems. More than a month after the launch of the redesign, Capital Metro was still moving stop locations in response to complaints that people had to transfer in places without good walking infrastructure. “If you’re going to go to more of a grid-based system and you’re going to have more on-street connections, then you really need to look at the pedestrian experience of those intersections,” Capital Metro’s Todd Hemingson said. (As of April 2019, only about 60 percent of streets in Austin have sidewalks.)

Improving the walk to transit, on the other hand, can have measurable impacts on transit ridership. Ja Young Kim, Keith Bartholomew, and Reid Ewing of the University of Utah found that after the Utah Transit Authority built sidewalk connections to bus stops that lacked them, ridership at those stops grew almost twice as fast as at stops in similar neighborhoods that had not been improved. Demand for paratransit was also stemmed near the stops with sidewalk improvements, saving the agency on its budget.

Although walkability and transit can’t be separated, government usually makes its best effort to do so. Just as transit agencies must convince cities to give transit priority on the street, they must rely on local and state government to create a good walking environment. That’s no given.

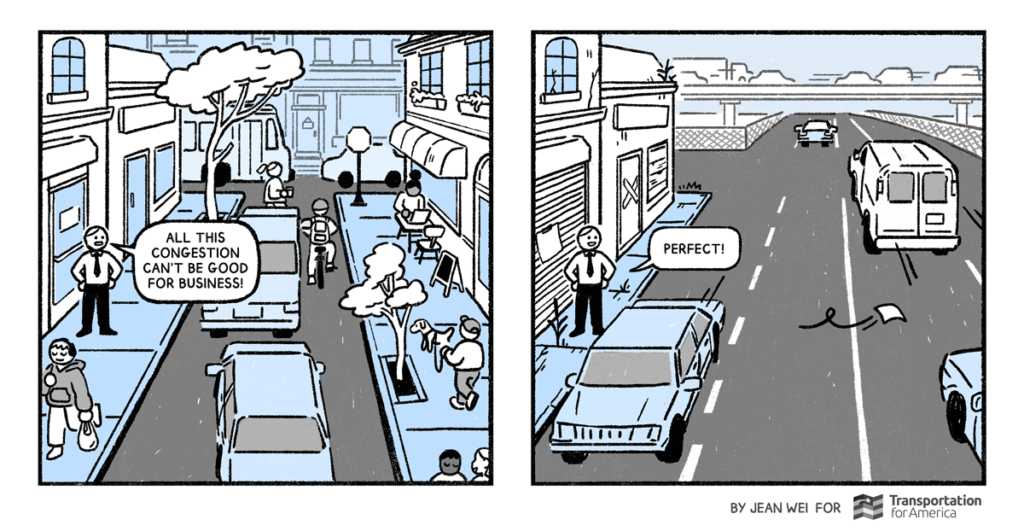

The state of walking in America represents an enormous collective failure. Even in urban neighborhoods where many people walk, engineering practices that favor drivers tend to degrade the experience. Intersections can be designed with slip lanes that allow cars to gun through turns. Zoning may allow curb cuts that turn the sidewalk into a gauntlet of traffic. The default rule at most intersections is “right turn on red,” intrinsically hostile to people walking because there’s never a time when they can be sure cars won’t turn into their path.

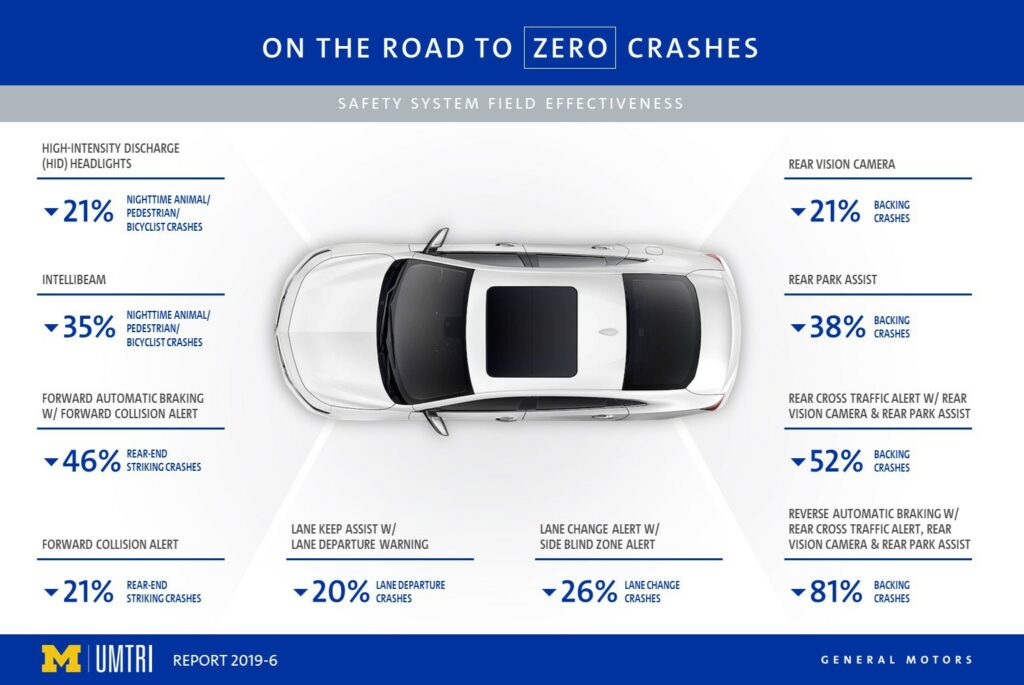

These decisions are rooted in a philosophy that prioritizes vehicle speeds and is often baked into engineering measures and practices. Engineers often assess streets using a metric called “automobile level of service,” where an A grade is free-flowing traffic. A major traffic engineering manual recommends against striping crosswalks unless at least ninety-three pedestrians already cross the intersection per hour—or if five people were hit by cars at the intersection in the past year. Peter Furth, an engineering professor at Northeastern University, has pointed out that “Synchro, the standard software [traffic engineers] use, is based on minimizing auto delay, and it doesn’t even calculate pedestrian delay.”

Although most streets are municipally maintained, most cities require local property owners to maintain sidewalks abutting their property. This means that wealthier neighborhoods tend to have better maintained and safer sidewalks. The further you get from downtown, the more likely it is that sidewalks themselves will shrink, decay, or vanish. Property owners may not be required to build sidewalks at all, which means many cities simply lack sidewalks in a huge portion of their territory.

Fighting for People on Foot

Pedestrian infrastructure doesn’t cost much relative to other transportation infrastructure. Houston’s $83 million in backlogged sidewalk requests could mostly be wiped out by nixing a $70 million project to add an interchange on an area toll road. Even the $1.4 billion price tag to build functional sidewalk on every Denver street doesn’t look so daunting when the Colorado Department of Transportation is spending $1.2 billion in just 4 years to widen Interstate 70, which runs northeast of downtown Denver.

Shelters aren’t particularly expensive either, costing roughly between $5,500 and $12,000 each. In 2017, medium and large transit agencies spent $297 million on infrastructure at bus stops and stations, compared with $2.2 billion on rail stations—or about 6 cents per bus trip and 47 cents per rail trip.

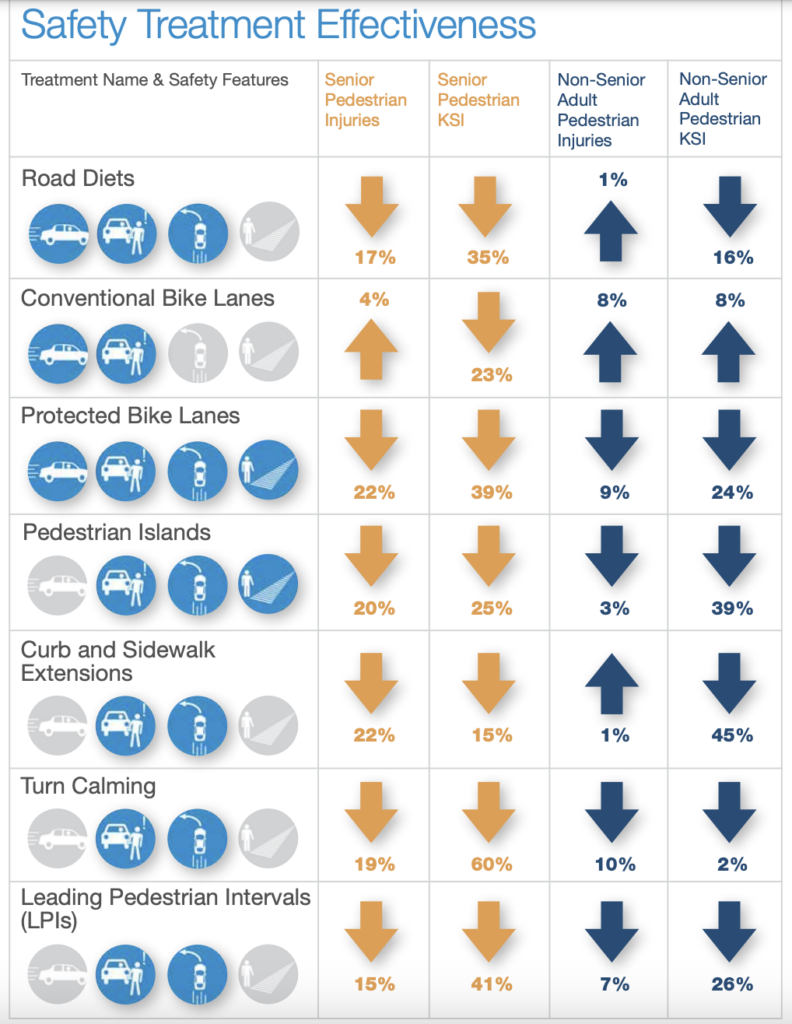

Creating walkable places requires changing municipal processes so that compact planning (creating neighborhoods where there are many destinations worth walking to) and pedestrian-friendly street design become routine.

This often starts with outside advocacy and political action.

The do-it-yourself movements I mentioned earlier in this chapter ultimately seek not to supplant government but to prod it to action. A year after MARTA Army launched its “adopt-a-stop” campaign, the state of Georgia awarded the Atlanta Regional Commission $3.8 million for bus stop signs, shelters, and sidewalks. Cincinnati’s Better Bus Coalition doesn’t just build benches; it has also published an analysis showing that shelters are disproportionately in wealthy neighborhoods. Streetsblog USA runs an annual “Sorriest Bus Stop in America” contest that has gotten governments in Kansas City, Maryland, and Boston to address bus stop walkability.

In Nashville, a long-time neighborhood activist, Angie Henderson, was elected to the city’s Metropolitan Council on a platform of walkable neighborhoods in 2015. Henderson later sponsored and passed a law requiring most developments in inner-city neighborhoods and near commercial centers to include sidewalks or pay into a citywide sidewalk fund. Denver’s City Council created a $4 million fund to help lower-income homeowners fix the sidewalks in front of their houses and budgeted for three new Public Works employees to manage the program and step up enforcement of sidewalk regulations throughout the city. And Seattle’s Department of Transportation has broken with the engineering guideline that says crosswalks should be striped only where many people already cross or where there are frequent pedestrian crashes.

Within transit agencies themselves, it’s important to raise the profile of the walk and the wait. Metro Transit’s Better Bus Stops Program is a great example. The decision to elevate a routine process into a branded program gave bus stops new stature throughout the agency.

“[The process of siting bus shelters] could be thought of as very dull and unimportant,” Farrington said. “But to package it, to get a great little logo and have it be a substantial program with its own name and people, it’s been a positive spiral of more resources and more support of the work.” She said that staff who had previously worked on park-and-ride stations were now spending more time on bus stops. True, in some ways the program was an outlier, funded by an Obama-era discretionary program, Ladders of Opportunity, that no longer exists. But transit agencies could replicate it using funding from many other sources.

Metro Transit’s program also offers a clear example of how well-resourced, well-planned public engagement can strengthen and educate both the transit agency and the communities it operates in.

Thanks again to Steven Higashide and Island Press for allowing us to run this excerpt. You can buy his book direct from Island Press or find links to purchase at other various outlets there. -Ed