For well over two decades, we’ve had no big-picture guiding purpose for the federal transportation program. Like a ship with a jammed rudder heading off aimlessly into forever, federal transportation policy has been limping along without an overarching purpose or destination in mind. How does this inertia lead us toward all the wrong things?

Is the purpose for the ~$60 billion in federal funds we spend each year merely to increase driving? To add more lane-miles? To ensure that pavement totals increase? To simply build some new stuff and try to keep up with the old stuff? To better connect people with opportunity in a measurable way? Here are six policies embedded in current transportation policy that are not a product of an intentional conversation about what we should accomplish, but rather the result of having zero direction and purpose since we completed the interstate system in 1992.

1) States are rewarded financially for encouraging more driving and longer trips

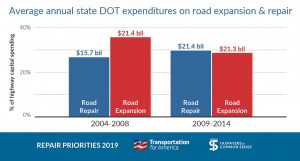

It’s no mystery why states spend too much of their money building new lane-miles, new roads, and new bridges at the expense of repair and everything else: The financial payout for states is based on increasing driving as much as possible.

The bulk of all federal transportation money is doled out to states based on a series of formulas tied largely to population, number of lane-miles, and how much everyone drives (vehicle miles traveled, or VMT). If a state encourages more driving or if everyone takes longer trips, that state receives more money the following year. Conversely, if your state finds ways to reduce driving by investing in transit, more logically planning jobs and housing in better proximity to one another, or finding creative ways to manage travel demand, your state loses money.

Put another way, perhaps the most core, embedded philosophy of the federal transportation program is to increase driving—as if more driving itself is an unmitigated economic and societal good.

2) Federal programs originally designed to support and encourage long distance driving are poorly suited to fulfill more complicated modern needs

“Most state departments of transportation were created largely for one reason: to implement a highway-building program,” wrote T4America director Beth Osborne in this series on the Smart Growth America blog, and even the most forward-looking of state DOTs today still have that highway-building DNA embedded deep in their culture. Today’s aimless federal program needs to accomplish far more than the original intended purposes of moving people long distances across states or between metro areas. Yet we still try unsuccessfully to make this old, outdated system serve today’s needs. As Beth wrote in the opener for that series, “the same department that delivered this highway below on the left a few decades ago is the same one tasked with delivering the street on the right, perhaps right in front of your house.”

Our transportation needs have changed, but the federal program has failed to keep up.

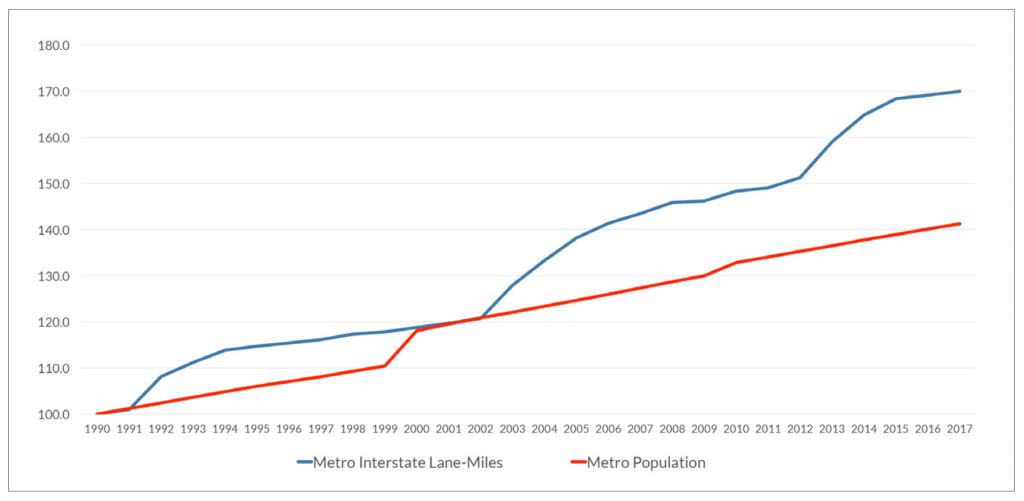

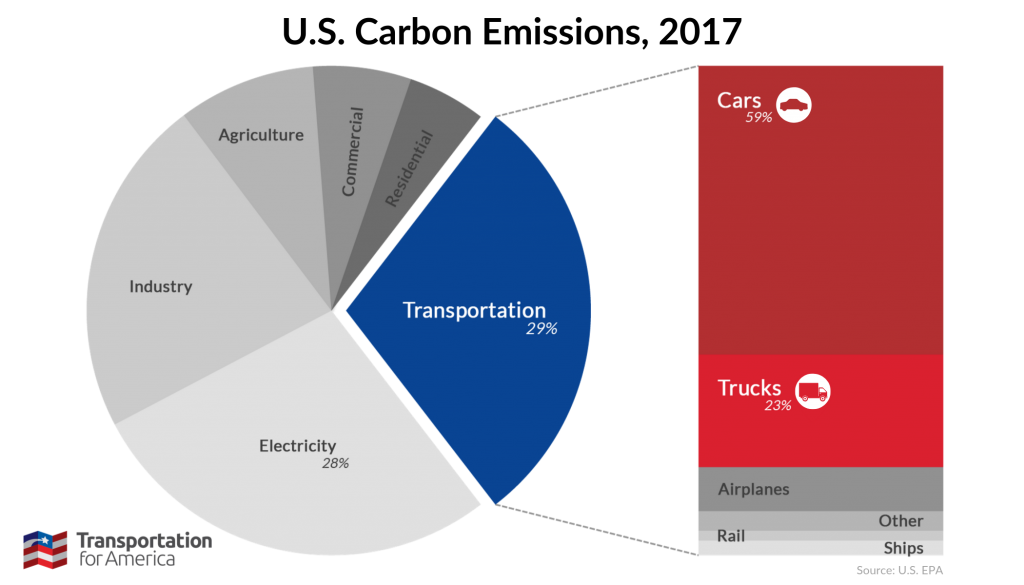

3) Transportation emissions are growing because the program is designed that way

Transportation is the #1 sector for emissions and driving represents 83 percent of those emissions. These emissions are rising because people are forced to make more and longer trips. The U.S. has added metro interstate lane miles faster than our metro population has grown, increasing greenhouse gas emissions and obliterating the modest gains made in more efficient vehicles and cleaner fuel. With new roads subsidized by the federal government (covering around 80 percent of the cost), localities struggle to stay ahead of development that spreads further from the center of metro areas, forcing people to travel further to access jobs and services. This leads to a demand for more roads, which induces even more driving and pollution.

We simply can’t continue expanding our roadway network and lower emissions at the same time. The two goals are incompatible, and unfortunately, increasing driving is a purpose embedded deeply in the program. If the main policymakers in Congress can stop talking about money long enough to do so, it’s past time for a conversation about making shorter trips and shared trips a core goal and purpose of the program.

4) We subsidize driving at the expense of providing any other options

Given a transportation challenge to solve, the federal program puts its thumb on the scale in favor of a road “solution” by covering about 80 percent of the cost, while only providing about half of the cost for a transit solution to the same problem. On top of that, not only do we make transit projects jump through more hoops in an arduous development process that no highway projects are subject to, but we actually hold them to a more realistic standard of long-term affordability. As we wrote for Strong Towns last week, “with new federally funded transit projects, agencies have to prove they have sufficient funding to operate and maintain the new line or service, and can do so without shortchanging the rest of their system.”

The federal program encourages costly over-expansion because it doesn’t require states to prove they can afford to maintain what they’ve been encouraged to build in order to get more federal money. Congress is perfectly fine with states building a new road they can’t afford to preserve long-term, even as they are failing to maintain the rest of their system in a good state of repair. And then, as we wrote in Repair Priorities, “those states return to the federal government every few years requesting more funds to address their unmet ‘needs,’ when those needs could have been prevented or delayed with more responsible spending practices.”

That’s why we’re in this goofy situation where every state and every lawmaker seems to thinks the problem is just a lack of money.

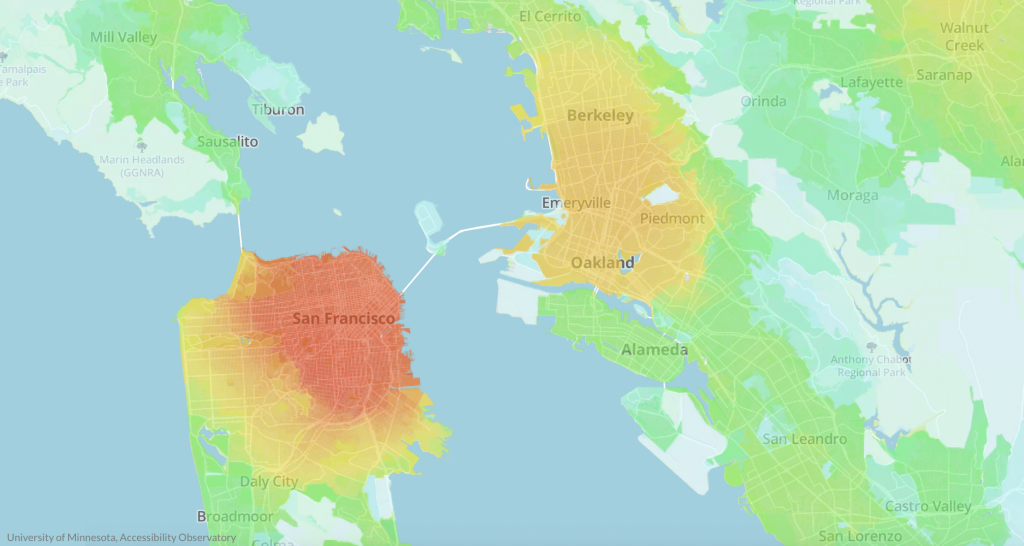

5) The program asks the wrong questions and measures the wrong things

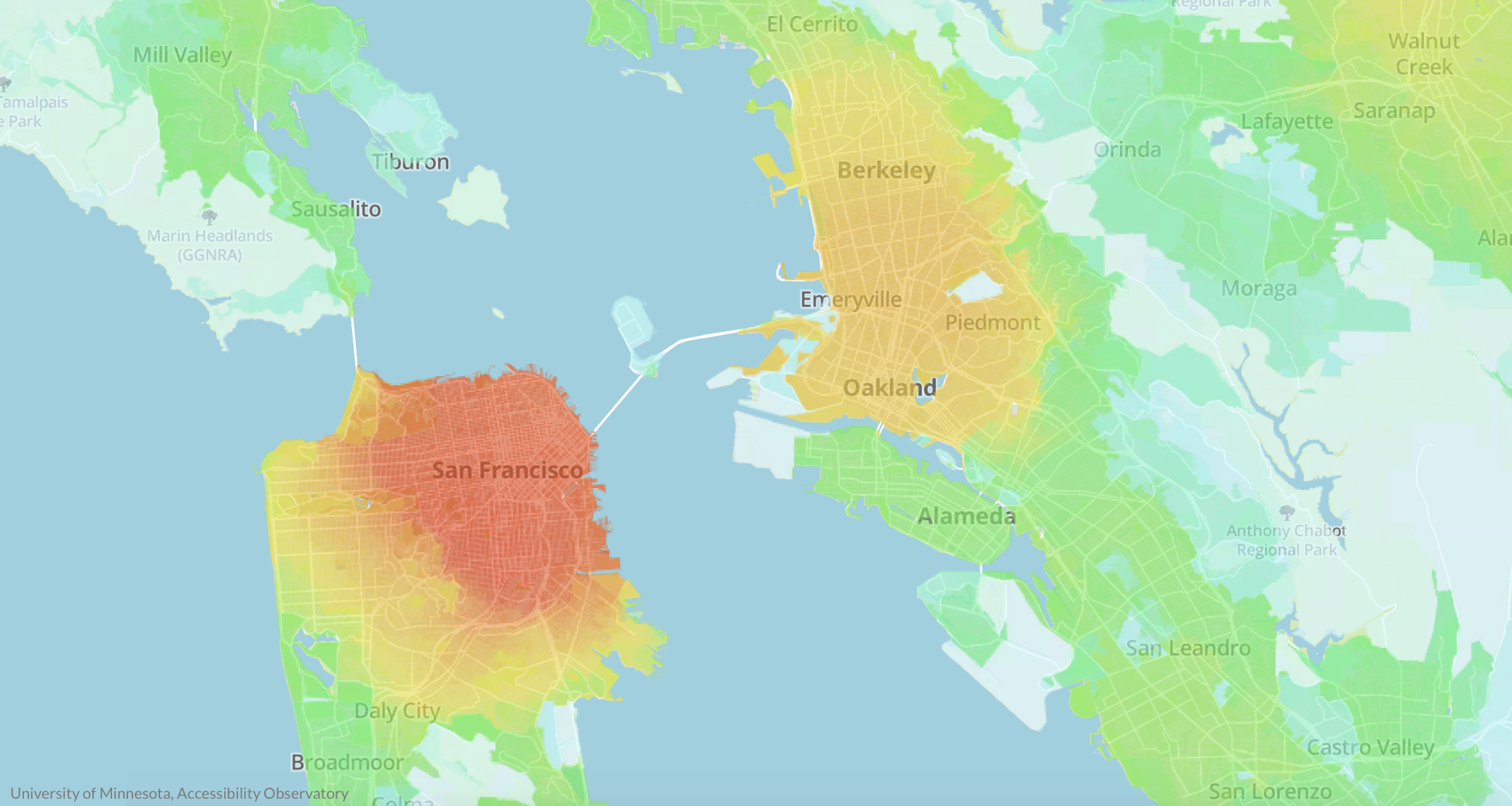

The program is obsessed with vehicle speed and you can see it in the few, limited ways that we try to measure whether or not our system succeeds. If you have a 15-minute commute to work in congested urban street traffic, are you better off than if you have a 45-minute commute in traffic that moves quickly? All of the incentives embedded in the program related to how we measure and assess congestion would prefer the second commute. And because free-flowing traffic is considered the gold standard, roads are built to ensure that traffic flows quickly, and this is what leads us to more and wider roads, and more and longer trips. (And streets that are then uninhabitable for anyone walking or biking.) Perhaps, a better measure would be assessing whether or not people can reach jobs and services by any mode of travel, rather than the simplistic measure of whether some of them travel at high speed when driving.

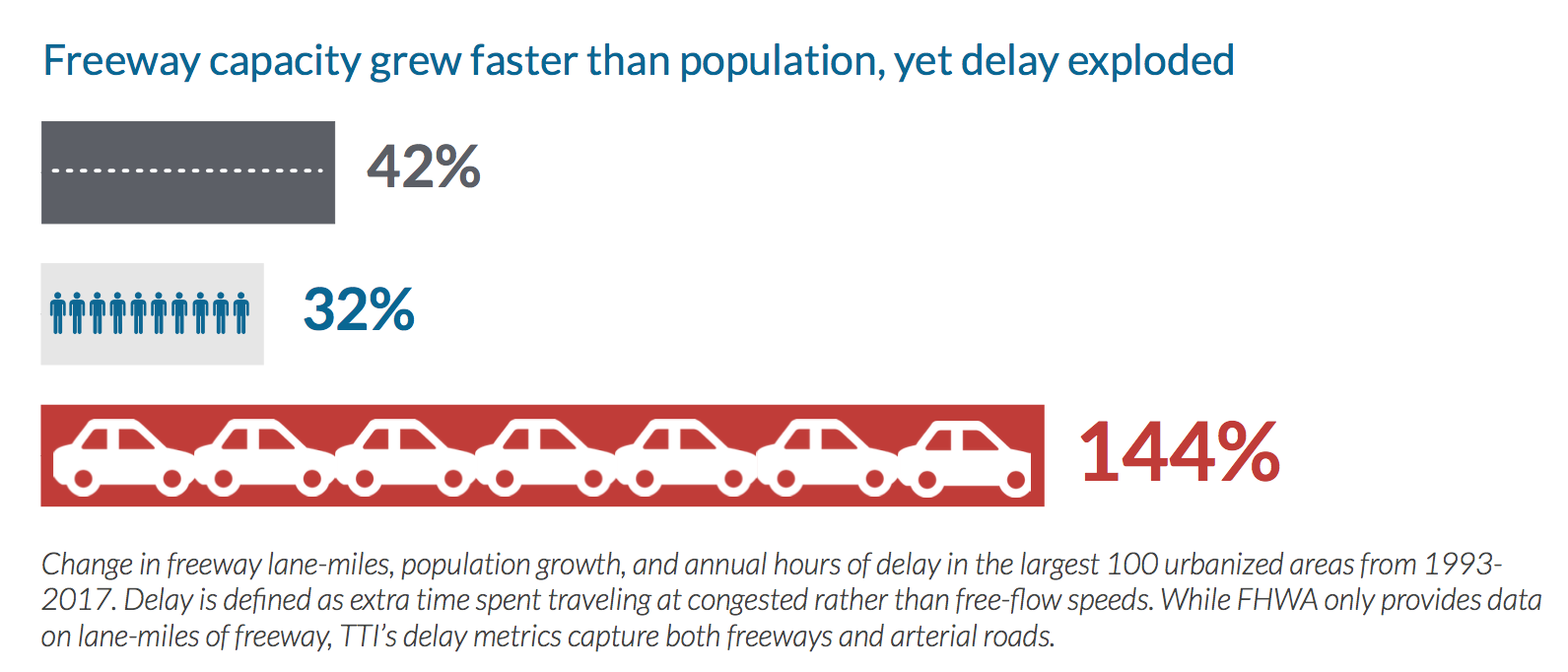

6) We undercut all our other priorities with a strategy to reduce congestion that fails every single time

The federal program is obsessed with reducing congestion, yet everything we do to reduce congestion just makes it worse.

A new study from Cal State Northridge showed that increasing lane-miles increases driving proportionally: a one percent increase in lane-miles results in a one-percent increase in driving. The best part? Expanding roads also fails to improve traffic: the speed increases from highway widenings disappear in five years because of more traffic. We expanded the country’s road system by about three percent from 2009-2017, guaranteeing at least a three percent increase in driving right there. On top of that, it’s impossible to square the priority of speed with the other things we want to accomplish, like improving safety, increasing reliability, or lowering emissions. From the SGA series:

This assumption of “the cars need to always move fast and never slow down” is at the root of most of the big problems that [state DOTs] face. Engineers have a prerequisite—sometimes explicitly stated but always implicit in the agency’s culture of practice—that makes every other priority a nearly impossible task. In practice, what this turns into is a list of secondary goals states would like to accomplish, that usually get sacrificed for the real top priority of speed. Until we come to grips with the fact that moving cars fast at all times of day without delay is a goal that can’t always be squared with all of the other priorities, until we can admit that perhaps everyone is not going to be able to go fast all the time, we’ll continue building unnecessarily large and expensive roads where speed is the number one priority and most other priorities fall by the wayside.

Make sure the vehicles can always go fast

|

AND |

- Prioritize repair first

- Keep everyone safe, including people walking & biking

- Create vibrant places worth visiting

- Keep your costs low

- Don’t negatively impact nearby communities

- Help connect everyone to jobs and opportunity, whether they drive or not

- Promote sustainable and lasting economic development

- Reduce transportation-related emissions

|

Wrapping up: It’s past time to make some new goals for what this program is supposed to accomplish

Back in the 1950s we dramatically reshaped our federal transportation policy around accommodating high speed vehicle travel, and our federal program functioned with this unifying purpose for decades. Brand new highways made cross-country and inter-state travel easier than ever before, boosting the national and local economies by connecting places that weren’t well-connected before. But they also started to transform the way we we built homes and destinations by enabling easier travel from cities to their fringes. Today, the challenge is making sure people have access to jobs, services and amenities within easy distance of their homes. To accomplish this, we will need to remove barriers, build bridges (real and metaphorical) and provide safe, affordable convenient alternatives to get around.

Rather than limp along, plowing billions into adding a lane here or a new road there with no equivalent economic return, let’s state a set of clear, explicit goals for the federal program, guaranteeing less driving, more options, healthier communities, and less pollution—all things we should be encouraging as we near the quarter pole of the new century.

Politicians (and the media) love to bemoan our “crumbling roads and bridges.” That must mean we need more money to fix them, right? Here’s a secret: most of the billions we spend every year on our infrastructure

Politicians (and the media) love to bemoan our “crumbling roads and bridges.” That must mean we need more money to fix them, right? Here’s a secret: most of the billions we spend every year on our infrastructure

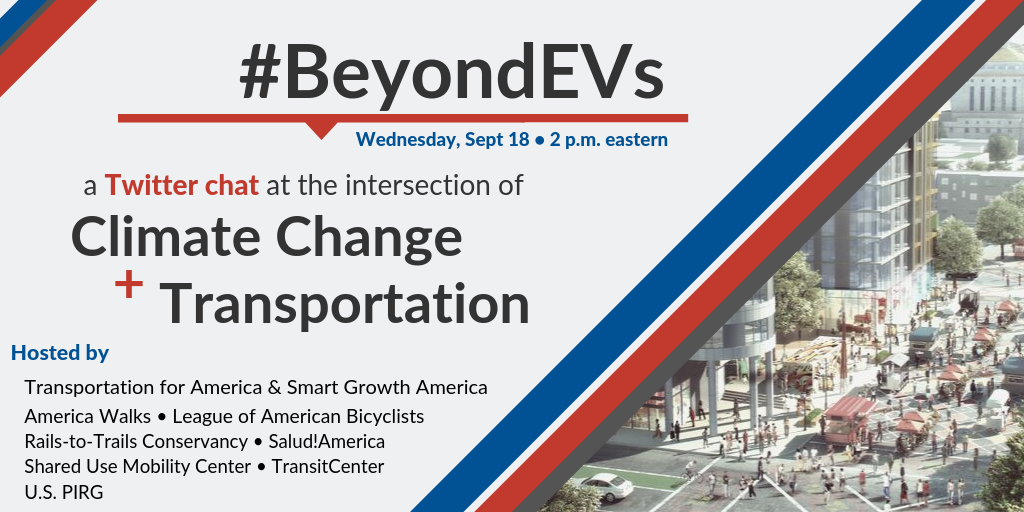

Last week, Representatives Chuy García (IL-4) and Ayanna Pressley (MA-7) co-hosted a briefing on Capitol Hill on the nexus of transportation and the climate crisis and announced the imminent launch of a caucus focused on creating a new vision for our transportation system.

Last week, Representatives Chuy García (IL-4) and Ayanna Pressley (MA-7) co-hosted a briefing on Capitol Hill on the nexus of transportation and the climate crisis and announced the imminent launch of a caucus focused on creating a new vision for our transportation system.