The following is a memo published by Third Way on ensuring smart infrastructure investments, written by Third Way‘s Transportation Policy Advisor, Alex Laska. Alex recently joined T4America Director Beth Osborne on a webinar, “Responding to the Crisis: What Does US Infrastructure Look Like During the COVID-19 Recovery?” presented by Third Way, Our Daily Planet, and the University of Michigan”. You can watch the webinar here.

The U.S. government has rightly focused first on dealing with the ongoing health crisis and minimizing the economic damage that American families and businesses are facing. Policy goals will ultimately have to broaden so we can spur economic activity and recover from the slow-down. We must focus on shoring up our economy and providing the smart funding and policy to put people back to work and make our economy more resilient to future shocks. A key component of that will be investing in our nation’s surface transportation infrastructure—but we have to do it right. Here are some principles to keep in mind if we want to get the most economic bang for our infrastructure buck:

Summary

Fix it First: Instead of focusing stimulus funds on building new infrastructure that we don’t need and can’t afford to maintain, let’s prioritize putting millions of people to work fixing the infrastructure we already have. This “fix it first” approach will create more jobs and get more money out to workers in a shorter timeframe—without needlessly encouraging extra driving and emissions.

- Require states to tackle a significant portion of their road and bridge maintenance backlogs before they can construct new lane-miles.

- Provide the $550 billion needed to eliminate road and bridge maintenance backlog, which will create as many as five million jobs.

- Require states that want to use stimulus funds for new road construction to demonstrate that they can afford to maintain the new infrastructure.

- Ensure state DOTs are equipped to spend the stimulus funds quickly by providing grants to build agency capacity and offering technical assistance on project selection and delivery.

Build it Back Stronger: Our infrastructure should be rebuilt to better withstand climate change and severe weather, keeping people and goods moving and getting our economy back up and running more quickly after future shocks.

- Fund a comprehensive assessment of the resiliency of U.S. infrastructure, so we can determine the full extent and cost of national resiliency needs and which projects are most critical.

- Establish a new funding stream to support projects that improve resiliency.

- Incorporate resiliency into federal highway funding formulas and competitive grant programs.

- Reestablish federal flood protection standards and apply them to all infrastructure spending.

Prepare for Tomorrow’s Needs: We also need to make sure we’re rebuilding our infrastructure to be relevant for the future. The federal government must make funds available to deploy the alternative fueling infrastructure needed to enable the coming transition to zero-emission vehicles. We also need to consider broadband deployment as part of our transportation infrastructure investments, ensuring the conduit is available to help underserved communities get access to broadband.

- Establish a new funding stream of at least $2.3 billion to support the buildout of public EV chargers and other alternative refueling infrastructure.

- Increase funding for the Alternative Fuels Corridors program to help states identify and address barriers to refueling infrastructure deployment.

- Implement a “Dig Once” policy so that broadband conduit will be included during the construction or reconstruction of any road receiving federal funding.

Fix it first: Prioritize maintaining the assets we already have over new construction

The premise of “Fix it First” is simple: federal dollars for surface transportation infrastructure should go towards repair projects before new construction. A “Fix it First” policy will get more money out faster to hire people, create jobs, and make our infrastructure more resilient than spending the same amount on new construction projects—while at the same time avoiding needless increases in vehicle miles traveled (VMT), congestion, and carbon pollution.

The extent of our repair needs: America has over $550 billion in road and bridge repair needs. Our road maintenance backlog—projects that would lift roads currently in poor condition into a state of good repair—is now $376.4 billion. On top of that, the U.S. has approximately 47,000 structurally deficient bridges, and it could cost nearly $171 billion to make needed repairs for all 235,000 bridges in the U.S.

Congress should invest the full $550 billion over five years in order to eliminate our maintenance backlog, make our transportation network safer, and put millions of Americans back to work.

How many jobs it would create, and how quickly: Investing in fully tackling the road and bridge repair backlog could create as many as five million jobs. According to an analysis of states’ Recovery Act reports, repair work on roads and bridges generated 16 percent more jobs per dollar invested than new road and bridge construction. This is largely because repair projects are more labor intensive—for example, they don’t need to spend as much money on land or right-of-way acquisition—so more of the money can go towards hiring workers.

A “Fix it First” policy would spend money faster and create jobs more quickly. New construction projects take longer to create jobs because they often require property acquisition or lengthy environmental or design review processes. Repair projects put money into the economy faster: most repair projects can be completed in one construction season, whereas most new construction projects take up to seven years to pay out.

Time is of the essence: weekly unemployment claims have hit an all-time high, with 6.6 million Americans filing a claim in the last week of March. A “Fix It First” policy will create the most jobs, and it will create them faster.

How it’s better for climate: Despite increases in the fuel efficiency of passenger vehicles, emissions from highway transportation have increased over the past decade largely due to an increase in vehicle miles traveled (VMT). Research has shown that constructing new lane miles leads to more driving, which in turn leads to higher emissions and more congestion. Conversely, prioritizing maintenance projects will help reduce emissions by slowing that growth in driving.

It is critical that we achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 in order to avoid the worst consequences of climate change, and that includes deeply reducing emissions from highway transportation. Even as Congress focuses on the more immediate objective of economic recovery, we cannot lose sight of our need to reduce emissions: “Fix it First” will help us avoid increasing VMT and emissions even further.

How to implement it: To maximize our surface transportation infrastructure investments, Congress needs to compel states to prioritize repair projects while ensuring states have the capacity to manage the influx of stimulus dollars.

- Stimulus funding for infrastructure should be limited only to repair projects so that states can tackle their maintenance backlog before using the funds to build something new. This idea has gotten some attention on Capitol Hill: House Democrats included a “Fix it First” policy in their January 2020 infrastructure framework, saying they would “revamp” the federal highway formula programs to prioritize maintaining and improving existing infrastructure.

- Congress should also require that any state that wants to use federal funds for network expansion must prove it can afford to maintain the new roadway capacity. Over the past 10 years, states have spent about an equal portion of the transportation infrastructure dollars on road repair and new road construction—all while the percentage of roads in poor condition increased from 14 percent to 20 percent. This is unsustainable in the long-run, and adding new lane-miles when it isn’t absolutely necessary will only make the problem worse. Requiring states to demonstrate they can maintain new infrastructure and not let it fall into disrepair will ensure more federal funding goes toward repair projects that spend money faster, create more jobs, and avoid emissions increases.

- To maximize our investment, we need to make sure state DOTs are equipped to handle such a large influx of new funding and get projects started quickly. Congress should provide grant funding for state DOTs that face capacity issues and should also provide funding to FHWA to provide technical assistance to state DOTs on project selection and delivery.

Building it back stronger: Rebuild our infrastructure to be more resilient to climate change and severe weather

As we rebuild our infrastructure, we shouldn’t just rebuild it exactly the way it was before—we need to fix our infrastructure so that it’s better suited to deal with climate change and severe weather. Extreme weather events like hurricanes, flooding, and wildfires are increasing, and so is the cost of rebuilding following those events. But the U.S. has failed to integrate resiliency into our infrastructure, chronically underinvesting in projects that would help the system recover after a shock. That needs to change: resiliency must become a factor in federal infrastructure funding decisions so we can ensure our transportation network can better withstand future disruptions and reduce the cost of maintaining the system over the life of these projects.

Determining our resiliency needs: Due to decades of failing to account for resiliency in our infrastructure investments, we don’t have a good tally of exactly what’s needed. We don’t know all of the bridges that need to be raised to higher flood levels, which projects are most urgent to ensure continuity, or which parts of the network are most vulnerable to which kinds of shock. For example, the Office of Management and Budget reported in 2016 that the total cost of replacing all federally-owned assets built in flood plains would exceed $1 trillion—but that includes all federal assets such as transportation and communications infrastructure, federal buildings, national security facilities, etc. The federal government needs to lead a comprehensive effort to assess the current condition of our transportation infrastructure from a resiliency standpoint, determining which projects are most critical and how much funding is needed.

How to improve resiliency: While we still need to get the complete picture of where our infrastructure resiliency needs are the greatest, we can begin getting money out the door for projects that state and local agencies have already identified. Federal programs like FEMA’s Pre-Disaster Mitigation Grant Program and Flood Mitigation Assistance Grant Program help states and communities plan for disasters and implement mitigation measures that reduce impacts from severe events like flooding. Programs like these can serve as a model for establishing a new, transportation infrastructure-specific program that awards funding on a competitive basis to projects that can demonstrate they meet certain resiliency criteria. Congress should:

- Establish a resiliency-specific funding stream of at least $5 billion, as included in the Senate Environment & Public Works Committee’s highway reauthorization bill. This program should be competitive so that state and local agencies must detail how the project would improve resiliency based on well-defined criteria.

- Direct USDOT to develop definitive resiliency criteria and use those criteria in federal funding decisions, not only in the aforementioned competitive grant program but also in the highway formula programs and other competitive grant programs like BUILD and INFRA. The House Democrats’ Moving Forward Framework called for including resiliency as a decision-making factor in project selection. This will help ensure that all transportation infrastructure funding considers resiliency and that we’re rebuilding our infrastructure to last.

- Reestablish federal flood protection standards and apply them to all infrastructure spending so that we can fully account for the future impacts of climate change and severe weather. This will ensure we’re spending taxpayer dollars wisely by directing funding away from locations that are most vulnerable like floodplains.

These policies are just a start. While we don’t yet know the entire scope or cost of our resiliency needs, there’s no question that after decades of failing to invest sufficiently in resiliency, a $5 billion grant program will not be enough. A comprehensive effort to identify and address our transportation infrastructure resiliency challenges, paired with a robust direct federal investment program, will help our network and our economy recover from future extreme events while also putting potentially millions of Americans to work making our infrastructure stronger.

Providing for tomorrow’s needs: Build out refueling infrastructure for zero-emission vehicles and broadband infrastructure

If we are going to spend hundreds of billions of dollars in repairing and upgrading our infrastructure, we need to make sure that infrastructure will remain relevant for decades to come. That means building out the electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure and other alternative refueling infrastructure to enable a rapid transition to zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs) such as plug-in hybrid vehicles, battery electric vehicles, and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. It also means getting as many communities as possible “cable-ready” by deploying broadband conduit during road construction, thereby saving money by reducing redundant excavation.

How many chargers we need, and what it will cost: According to the Center for American Progress, we need to deploy 330,000 additional public EV chargers by the end of 2025 in order to accommodate the growth in EVs needed to meet our Paris Agreement commitments. While fulfilling our Paris Agreement emissions reduction targets is not enough, it will put us on a starting path towards achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. This buildout will cost us $4.7 billion over the next five years; taking existing state resources and the Volkswagon “Electrify America” settlement funds into account, that leaves us with a $2.3 billion gap.

A $2.3 billion federal investment will help build out the infrastructure we need to rapidly transition to ZEVs, while creating thousands of manufacturing and construction jobs in the near-term. It will also provide a strong signal to consumers and automakers that the infrastructure to support ZEVs will be there as more are put on the road.

How to improve federal EV infrastructure programs: Many states have tax incentives and other policies to incentivize EV infrastructure buildout, but federal action has lagged behind:

- The Federal Highway Administration has an Alternative Fuels Corridors program that provides low-dollar grants for state and local transportation agencies to do the research and analysis work to identify and address barriers to EV infrastructure installation. We should expand funding for this program to help more transportation agencies develop alternative fueling corridors, including addressing right-of-way acquisition.

- While there are federal programs like the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) highway formula program and the DOE State Energy Program that states can use to fund charging infrastructure, states generally use those funds for other priorities. Congress should establish a separate funding stream of at least $2.3 billion, including direct federal investment and grants to state and localities, to deploy the needed infrastructure. The House and Senate committees of jurisdiction have both called for such a program.

How to save money with a “Dig Once” policy: The COVID-19 crisis has brought the digital divide into stark relief. At a time when more and more Americans rely on an Internet connection for telehealth and virtual learning, underserved communities are getting left behind. Building out our broadband infrastructure will help get more Americans online while also creating construction jobs.

Broadband is an enormously important issue and opportunity that deserves its own list of policy recommendations. But as we focus on transportation infrastructure, we should keep in mind that the same roads we’re constructing or rebuilding now might need to be dug up again in the future to lay down broadband fiber. According to FHWA, burying fiber optic cables and conduit underground is the largest cost element for deploying broadband, responsible for up to 90 percent of deployment cost when it requires major excavation of roadway. A “Dig Once” policy minimizing excavations could save $100 billion.

In order to reduce redundant digs and save money in the long-run, Congress should:

- Include a “Dig Once” policy requiring broadband conduit to be included during the construction or reconstruction of any road receiving federal funding, if the surrounding communities do not already have broadband access.

- Direct state and local agencies to collaborate with the Internet Service Providers in their communities to identify where this conduit is needed and work together to minimize redundant digs.

Conclusion

The unfolding economic crisis calls for bold, swift action to put millions of Americans back to work and stimulate economic growth. Improving our infrastructure is one of the smartest investments we can make to accomplish those goals. For too long, the federal government has embraced a transportation infrastructure policy that encourages new construction where we don’t need it and can’t afford to maintain it. We have an opportunity now to reshape how we invest in our transportation infrastructure—to prioritize fixing what we have before we build anything new, to ensure we’re rebuilding our infrastructure to be more resilient to future shocks including climate change and severe weather, and to build out the infrastructure we need to support a rapid transition to zero-emission vehicles. Combined, these policies will create millions of jobs, ensure our transportation network can better withstand future shocks, and help reduce emissions.

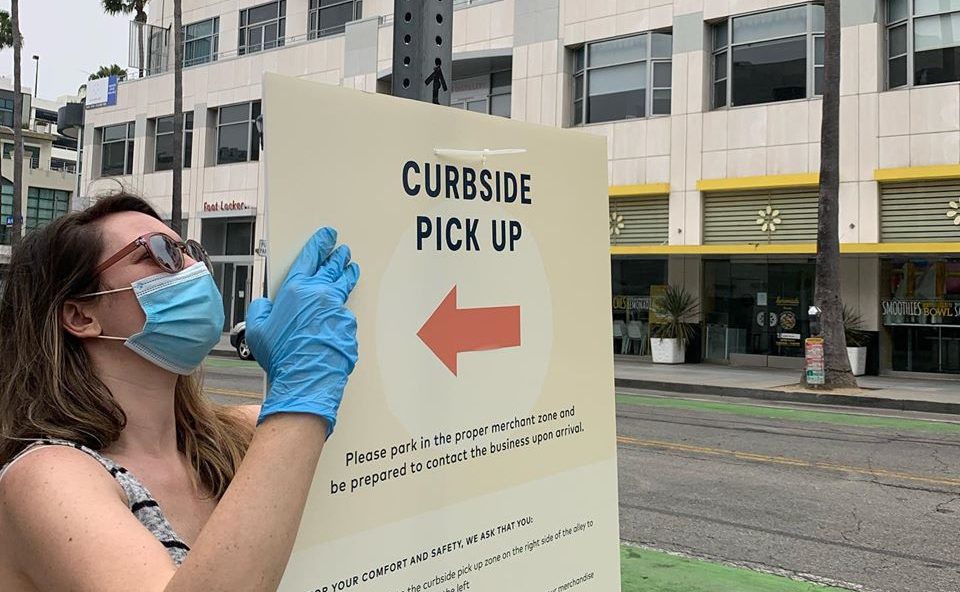

This blog is part of a special series on curb management and COVID-19. A joint effort of Institute for Parking and Mobility, Transportation for America, and the Institute of Transportation Engineers, this series strives to document the immediate curbside-related actions and responses to COVID-19, as well as create a knowledge base of strategies that communities can use to manage the curbside during future emergencies.

This blog is part of a special series on curb management and COVID-19. A joint effort of Institute for Parking and Mobility, Transportation for America, and the Institute of Transportation Engineers, this series strives to document the immediate curbside-related actions and responses to COVID-19, as well as create a knowledge base of strategies that communities can use to manage the curbside during future emergencies.