As we slowly settle into a new normal, transit agencies across the country are making big changes to their operations to keep employees and riders safe. We checked in with our transit agency members across the country to see how they’re adapting to COVID-19 and what they need to keep going.

Join us on Twitter all-day tomorrow (Thursday, September 17) for a #SaveTransit Tweet Storm. Tweet at your member of Congress to #SaveTransit using our social media toolkit, and send an email to your members using our action page.

A transit rider wearing a mask on the Washington, DC Metro. Photo by Elvert Barnes on Flickr’s Creative Commons.

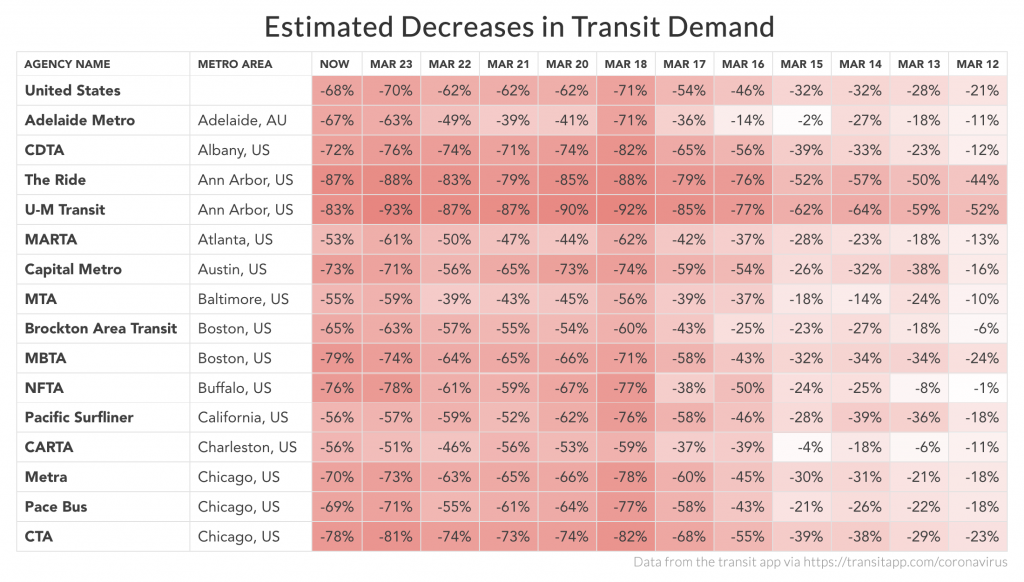

It’s been almost six months since COVID-19 radically altered our lives, and public transportation remains both vital and in a major crisis. The pandemic has shattered transit agencies’ funding sources, with necessary shutdowns and social distancing measures depleting revenue from fares and sales taxes.

It was already a perpetual challenge for agencies to keep trains and buses operating in pre-pandemic times, thanks to limited federal funding and a national transportation program that prioritizes driving over all other modes. But the added (and costly) challenge of keeping transit employees and riders safe from contracting COVID-19 has made operating transit safely and efficiently even more challenging. Transit agencies across the country are announcing major cuts to service, a consequence of plummeting revenues.

Transit agencies have a vital role in connecting people to jobs, healthcare, grocery stores and other essential services. Here’s what Transportation for America’s transit members are doing to keep employees and riders safe and connected to the things they need—and what will happen if the transit industry doesn’t receive at least $32 billion in emergency relief from the federal government.

Innovating on the fly

With limited federal guidance, transit agencies across the country often acted on their own to implement COVID-19 safety measures. Many transit agencies decided to suspend fare collection to reduce contact between riders and bus operators, and only allow rear-door bus boarding and install plexiglass shields at bus operators’ seats for the same reason.

Both Mountain Line (Missoula, MT) and DART (Des Moines, IA) began running “plug buses”—running two buses in tandem—to provide riders with more space to social distance on buses. Mountain Line, Pierce Transit (Tacoma, WA), and the Sacramento Regional Transit District also parked some of their buses to create community WiFi hotspots, providing another service essential to weathering the COVID-19 crisis, especially for students lacking internet service at home to continue their studies remotely.

Spending more than ever

Most transit agencies are spending more than they ever have on cleaning transit vehicles and personal protective equipment to keep their employees safe. Pierce Transit hired temporary employees to increase sanitizing buses. King County Metro (Seattle, WA) committed to cleaning buses every night, with special attention paid to ensuring the safety of cleaning staff. Most transit agencies acquired sanitizing wipes, hand sanitizer, and washable masks for employees—but struggled with procuring these essential items in the early days of the pandemic.

Cleaning isn’t the only category increasing costs—many transit agencies are giving employees more paid leave to ensure the health of themselves and their families. DART found that many of its bus operators fall into high-risk health categories, causing the agency to increase leave for high-risk employees and employees dealing with childcare issues as a result of school closures. Pierce Transit also allowed high-risk employees to take four to five weeks of leave, and took advantage of the federal Families First Coronavirus Response Act to provide employees with an additional 80 hours of paid leave for childcare. That’s good for employees, but it has also left some agencies without enough workers to provide essential service.

Without federal emergency relief, transit can’t go on

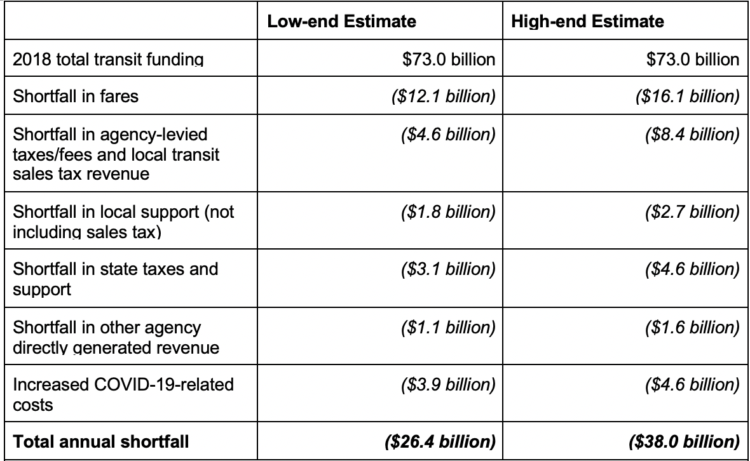

The double whammy of increased costs and decreasing revenue is slamming transit agencies—to the point where if they don’t receive emergency relief soon, they’ll have to drastically reduce service (or even cease to exist). While March’s CARES Act provided some relief ($25 billion in operating support), the financial hole public transportation is falling into has gotten much, much larger—at least $32 billion.

Transit agencies across the country are calling for at least $32 billion in emergency relief from the federal government, but Congress isn’t listening. Senate Republicans’ most recent COVID-19 relief proposal didn’t include any emergency funding for transit, and the House Democrats HEROES Act provided less than half of what transit needs. And both chambers of Congress are no closer to reaching any agreement whatsoever on a desperately needed relief package to provide support for transit, unemployment, the Payroll Protection Program, or other critical mechanisms for supporting Americans during this economic crisis.

Without transit, millions of people across the country will lose access to essential jobs, healthcare, and grocery stores—in the middle of a major, deadly pandemic. Losing transit service also erodes the prospect of any long-term economic recovery, with limited and infrequent transit service unable to connect people to opportunities and essential services they need.

Congress must include at least $32 billion in emergency operating relief for public transportation in the next COVID-19 relief bill, or leave your constituents stranded.

Tell Congress that they needed to pass emergency relief for transit yesterday. Email your members of Congress using our action page and tweet at your Congressional delegation to #SaveTransit using our social media toolkit.

It’s time for Democrats and Republicans—and more of the press—to think about what a transportation program can and should achieve: access to jobs for rich and poor, a safe travel environment for those in and out of a car, and a well-maintained system. None of these goals are partisan. Democrats and Republicans may come to each priority for slightly different reasons, but there is a new bipartisanship that can emerge around creating a better transportation system if we just look at what we are building and not just how much we can build.

It’s time for Democrats and Republicans—and more of the press—to think about what a transportation program can and should achieve: access to jobs for rich and poor, a safe travel environment for those in and out of a car, and a well-maintained system. None of these goals are partisan. Democrats and Republicans may come to each priority for slightly different reasons, but there is a new bipartisanship that can emerge around creating a better transportation system if we just look at what we are building and not just how much we can build.