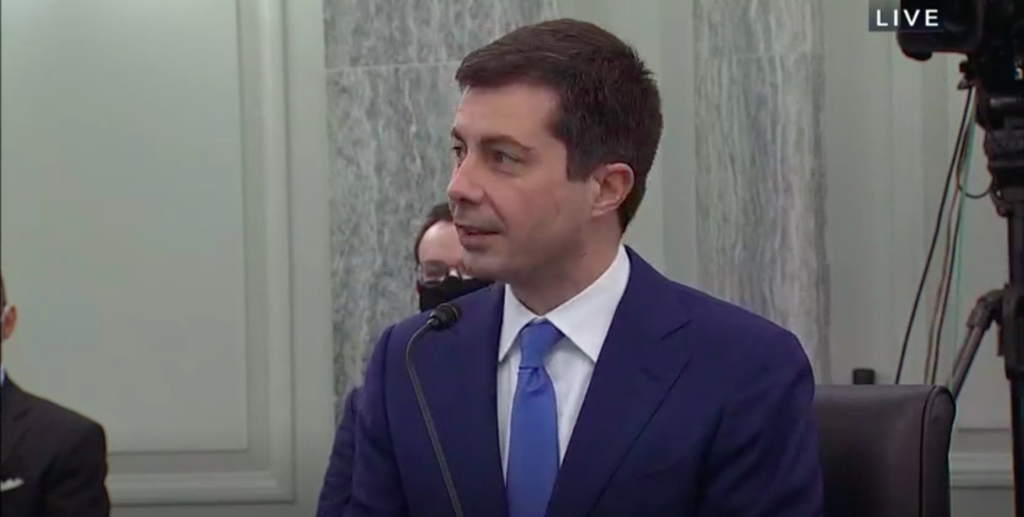

Last Thursday, former South Bend mayor Pete Buttigieg faced the Senate for questioning on his nomination to be Secretary of Transportation. We liked almost all of his answers, and we weren’t alone: Senator Tester said Buttigieg’s testimony was “refreshing.” Here’s what T4America liked and didn’t like from Buttigieg’s confirmation hearing.

Former South Bend mayor Pete Buttigieg facing the Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee as President Biden’s nominee to be Secretary of Transportation. Screen grab from C-SPAN.

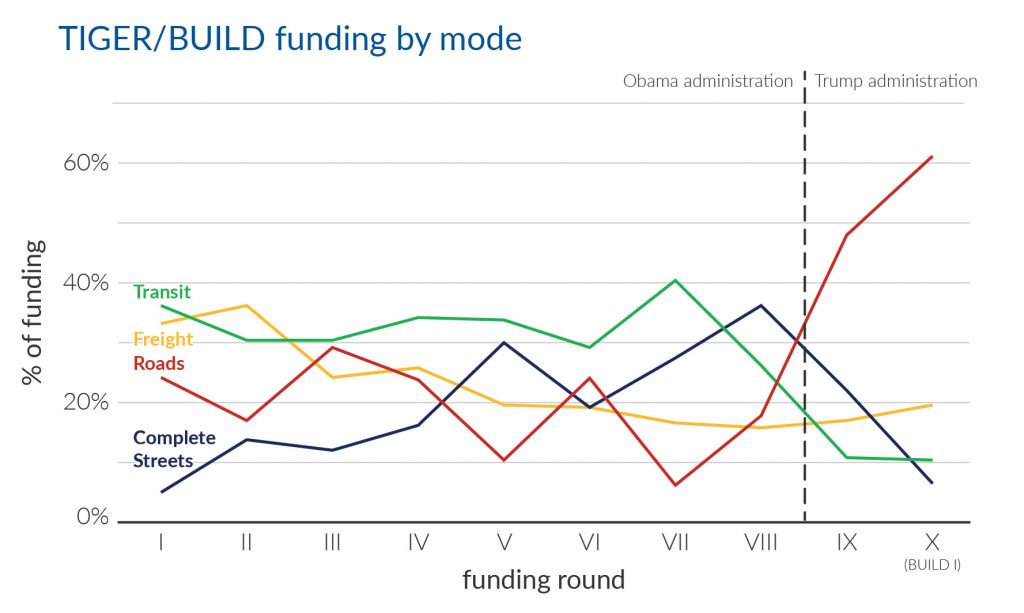

✅ Complete Streets is a priority for Buttigieg

When answering a powerfully-worded question from Senator Schatz (D-HI), a cosponsor of the Complete Streets Act, Buttigieg confirmed his commitment to a Complete Streets approach. He even highlighted the Complete Streets projects that took place in South Bend. (Smart Growth America provided technical assistance to South Bend to pursue Complete Streets demonstration projects.)

“It’s very important to recognize the importance of roadways where pedestrians, bicycles, vehicles, any other mode can coexist peacefully. And that Complete Streets vision will continue to enjoy support from me if confirmed,” Buttgieg said.

✅ Our “autocentric view” is a problem

Doubling down on his commitment to Complete Streets, Buttigieg noted that transportation in the United States overwhelmingly prioritizes cars. “There are so many ways that people get around, and I think often we have an autocentric view that forgets historically all of the other different modes,” Buttigieg told Sen. Klobuchar (D-MN). “We want to make sure that every time we do a street design that it enables cars, bicycles, and pedestrians, and businesses and any other mode to coexist in a positive way. We should be putting funding behind that.”

✅ Addressing past damages is a priority

Transportation infrastructure—particularly urban highways that have demolished and divided communities of color—is sometimes a major roadblock to improving equity in this country. Buttigieg knows this and told senators so in his opening remarks. “I also recognize that at their worst, misguided policies and missed opportunities in transportation can reinforce racial and economic inequality, by dividing or isolating neighborhoods and undermining government’s basic role of empowering Americans to thrive,” Buttigieg said.

✅ Policy hasn’t kept up with automated vehicles

Automated vehicles (AVs) is one of the transportation technologies that often captures lawmakers’ imagination. But in response to Sen. Fischer (R-NE), Buttigieg acknowledged that the federal government has failed to provide the leadership necessary to ensure that AVs actually deliver the benefits they promise. “[AV technology] is advancing quickly and has the potential to be transformative, but in a lot of ways, policy hasn’t kept up,” Buttigieg said.

This couldn’t be more true. After investigating deaths from two separate AV crashes, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) billed the utter lack of federal safety performance standards as one of the causes for the fatalities.

But proactive federal policy is needed for more than just ensuring that AVs are safe. Policy is needed to ensure that AVs are equitable, accessible, and sustainable. That’s why we joined Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety and other partners in creating tenets for AV policy.

✅ He supports passenger rail

Buttigieg said he’s the “second biggest enthusiast for passenger rail in this administration,” referring of course to President Biden, a long-time rider and fan of Amtrak, as the first. “Americans deserve the highest standard of passenger rail,” Buttigieg said.

When Sen. Roger Wicker (R-MS)—a major supporter of restoring passenger rail to the Gulf Coast—asked Buttigieg if he’s a rail rider himself, Buttigieg said he enjoys short rail trips “and long ones too.” In light of Amtrak’s proposal to cut its long-distance network, this might signal Buttigieg’s support for those critical routes.

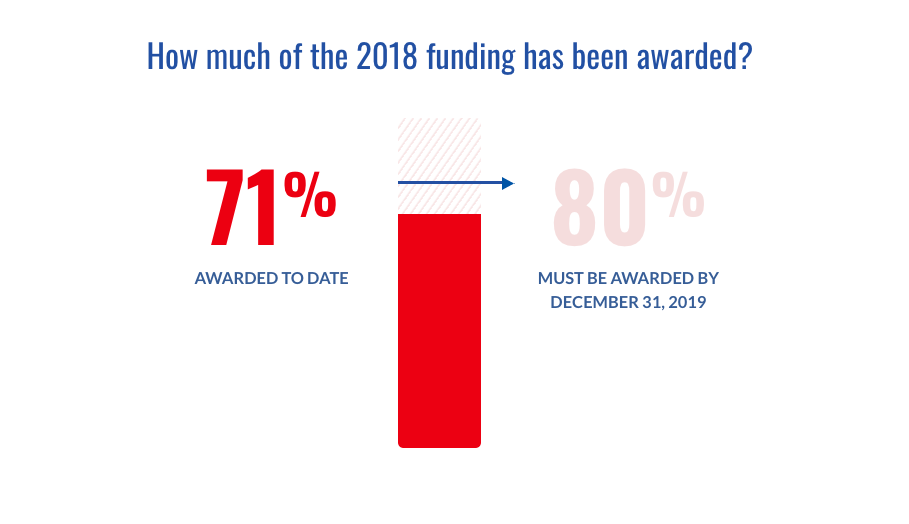

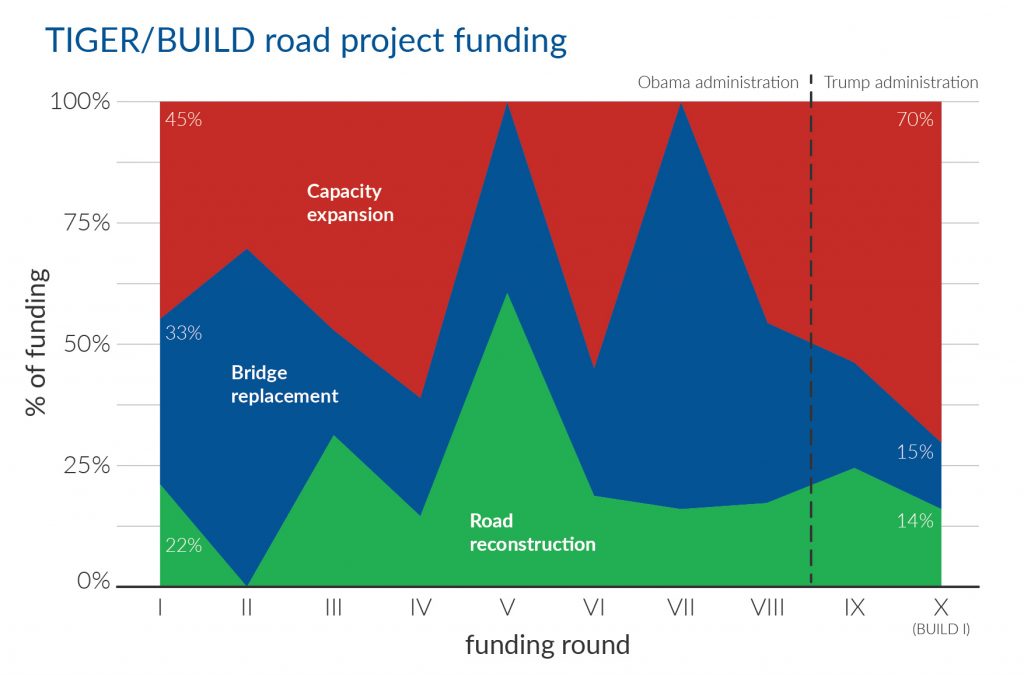

✅ The BUILD program should be easier to apply for

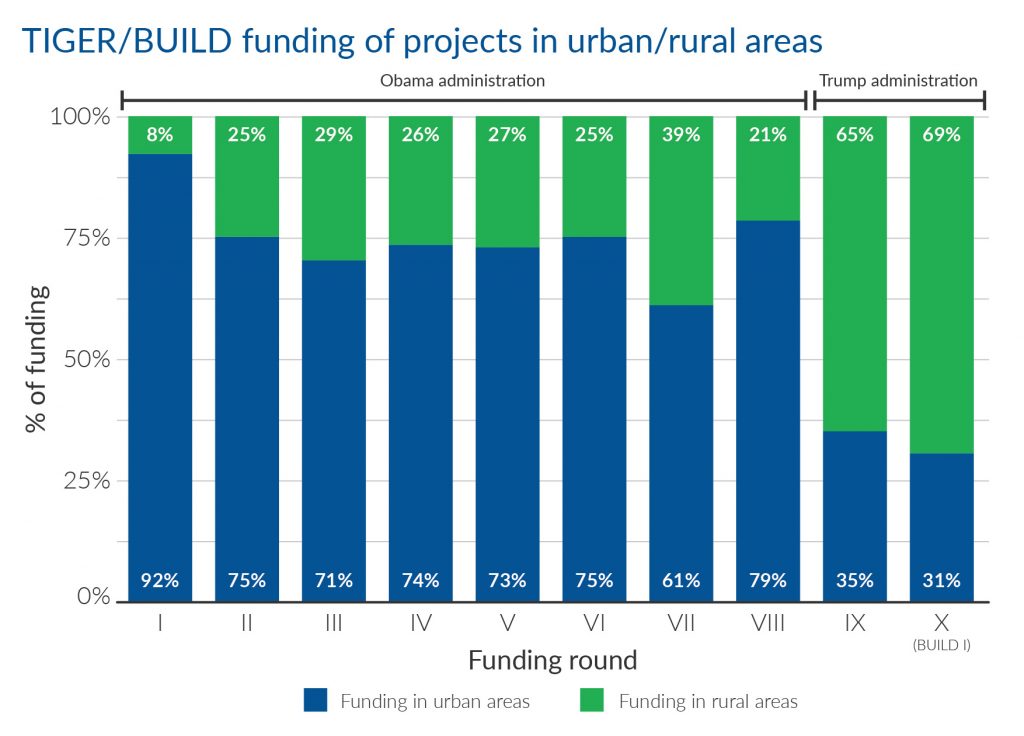

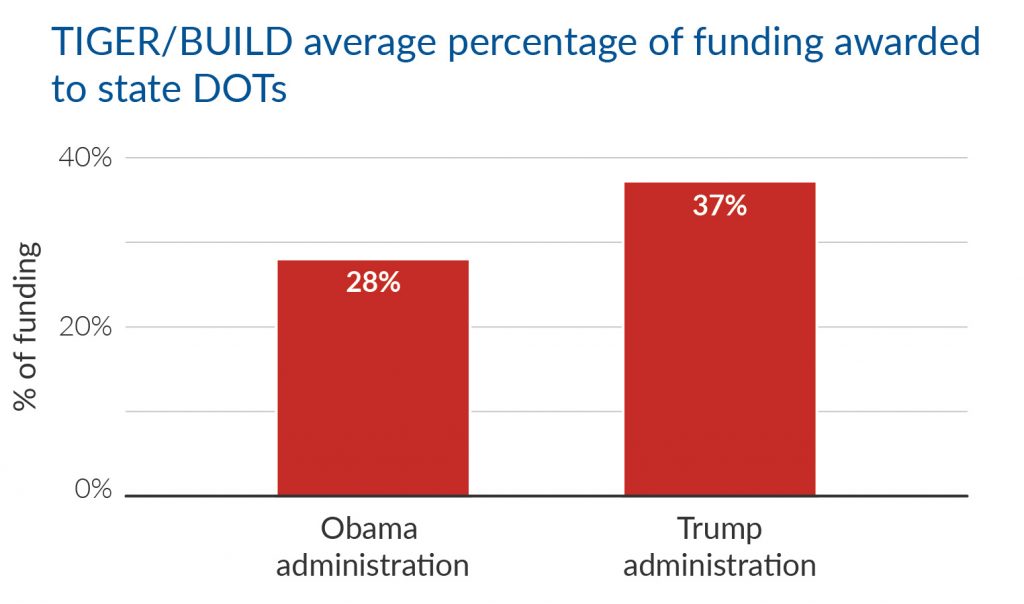

The U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) offers a host of grant programs for cities and towns to construct and maintain transportation infrastructure. But the application process is often daunting for smaller entities. As mayor of a small city that wasn’t able to have “full-time staff managing federal relations,” Buttigieg told Sen. Wicker (R-MS) that making BUILD and INFRA grants easier for small and rural municipalities to apply for are one of his priorities.

“It’s very important to me that this process is user-friendly, that criteria are transparent, and that communities of every size, including rural communities and smaller communities, have every opportunity to access those funds,” Buttigieg said.

✅ Senators on both side of the aisle support Buttigieg

Buttigieg felt the love from both sides of the aisle during his confirmation hearing, with Sen. Tester (D-MT) going as far to say that Buttigieg’s testimony should serve as a model for other nominees facing Senate approval. Sen. Wicker (R-MS) listed Buttigieg’s accomplishments in his opening statement, praising his “impressive credentials that demonstrate his intellect and commitment to serving our nation.”

With slim Democratic majorities in both the House and Senate, bipartisanship will be key to passing surface transportation authorization. But historically, infrastructure is one the areas where lawmakers bipartisanly agree to pass bad policy—rather than ruffling feathers and taking a hard look at what the federal government spends money on and why. (We blogged about it here.) It will take lots of work—like the herculean effort the House underwent this summer to pass a new kind of transportation bill—to make sure that the long-term transportation bill lawmakers must pass this year actually connects funding with the outcomes Americans want.

🚫 His climate answer only mentioned electric vehicles

When Sen. Schatz asked about Buttigieg’s approach to climate change, Buttigieg only discussed electric vehicles, charging infrastructure, and increased vehicle fuel efficiency as a solution. Yet it’s a fact that electric vehicles and improved fuel efficiency—while critical—aren’t enough to reduce transportation emissions on their own.

While we applaud Buttigieg’s support of President Biden’s “whole government” approach to addressing climate change (meaning that climate work isn’t confined to a single department like the EPA), we need Buttigieg to understand that USDOT needs to do more than invest in electric vehicles as a climate solution.

We like what we heard. Now let’s make sure it happens

Buttigieg might be one of the most promising new Secretaries of Transportation that we’ve seen, but we must hold him accountable to following through on these initiatives. Now is not the time to lay back: we have a lot of work to do to ensure that USDOT does what it can internally to connect transportation funding to the outcomes Americans want (like our three principles) and that Congress passes a long-term transportation bill that ends decades of broken, misguided policy.