Browse the report

POLICY GOALS

- I: Increase accountability and transparency to build taxpayer confidence

- II: Make states economically competitive; empower locals to do the same

- III: Invest in innovation and reward the smartest projects

- IV: Maximize savings through better project development

- V: Improve safety through better street design

Download the full report (pdf)

Join the START Network

T4America supports efforts to produce and pass state legislation to increase transportation funding, advance innovation and policy reform, empower local leaders and ensure accountability and transparency. Join the network.

State policy & funding home

Click here to visit our central hub for all state policy and funding resources, including our work tracking proposals in states to raise new transportation funding or reform the policies governing those funds to improve how those dollars are spent.

Stay informed

Sign up to receive news and updates from T4America. All fields are required.

Goal II: Make states economically competitive; empower locals to do the same

OVERVIEW

Improving a state or region’s economic competitiveness is one of the primary reasons for investing in transportation. Goods and people have to move, and the smoothness with which they move is fundamental to a prosperous economy. The investments needed to best position a state or community for long-term success have changed dramatically over the last few years. The formulas and mechanisms that determine where money goes and how it gets spent need to change to keep up with a different time than when those formulas were created.

Local communities need the flexibility to invest in the best projects that will help them succeed, regardless of what particular transportation option fits the bill. After all, local governments are best able to prioritize and plan for a community’s specific needs, and also have authority over land use and development decisions.

Even though local governments own and manage the majority of all roads, bridges and public transportation systems in the country, state agencies regularly diminish the role local stakeholders play in the policy development and project selection process and some restrict local governments’ ability to raise local dollars for their transportation priorities.

The state DOT is often the policy and project decision-maker in both rural and urban areas of the state. In too many cases, DOTs appear inflexible in working with local interests, while prioritizing the movement of vehicles over state-owned roadways at all expense. This outsized authority frequently places the DOT at odds with local priorities of creating safer, more economically thriving, complete streets. It’s important — and politically practical — for states to recognize the significance of local stakeholders as equal partners in maintaining and building the transportation system. Local elected and civic leaders should be powerful allies for state legislators, and leveraging those partnerships makes political — and practical — sense.

PROPOSAL #3

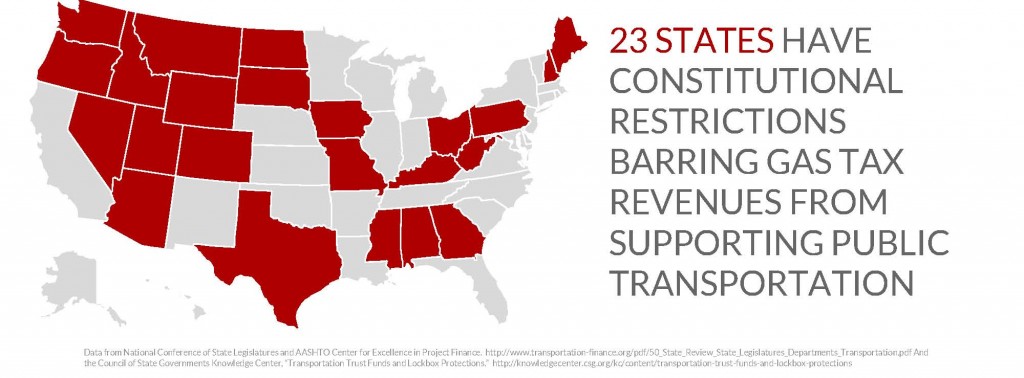

EASE CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY RESTRICTIONS ON FUNDING

Twenty-three states have out-of-date constitutions that impede economically important public transportation projects by restricting all or most state transportation-generated funding to roadway projects. Preventing state resources from funding public transportation can severely hamstring the economic competitiveness of a state’s metropolitan areas, where transit is becoming a fundamental requirement to be competitive for talent and job attraction, and is vital for connecting employees to jobs and easing roadway congestion.

Colorado, directly witnessing the massive benefits of Denver expanding its public transportation system over the past decade, has taken some strides to ease its restrictions on spending state funds on public transportation through statutory changes.

In 2013 the state legislature passed SB 13-048, which declared:

The general assembly further finds and declares that the funding of transit-related projects constitutes maintenance and supervision of public highways because it will help to reduce traffic and thereby reduce wear and tear on public highways and bridges and increase their reliability, safety, efficient performance, and expected useful life.

The bill permits state transportation-generated funds directed to counties and local governments to be invested in public transportation, bicycle and pedestrian projects. There is no limit on the percentage that can be spent for capital purposes; there is a limit that no more than 15 percent may be spent on transit operations.

The bill permits state transportation-generated funds directed to counties and local governments to be invested in public transportation, bicycle and pedestrian projects. There is no limit on the percentage that can be spent for capital purposes; there is a limit that no more than 15 percent may be spent on transit operations.

While that statutory change helps Colorado get to their desired outcome, states should consider providing true flexibility by allowing all transportation revenues to go to the best projects, regardless of transportation option. A constitutional change is a tough road to travel, but it may be the solution in many states.

PROPOSAL #4

REFORM OUTDATED DISTRIBUTION FORMULAS

States often use complex funding formulas — sometimes drawn up decades ago — to determine where and how incoming revenues are directed to various modes of transportation, to geographic areas, or to other entities.

Following their 2012 package to raise new transportation funding, Virginia went a step further and reformed its funding distribution formulas in 2015. HB 1887 reformed the confusing, outdated and complicated funding formulas that determined how money is distributed, and supports the state’s move to award more funds competitively.

Under the new formula, 45 percent of all funds will be reserved for maintenance and repair. The remaining 55 percent will be split evenly between priority state projects picked through a new, performance-based ranking process established by 2014’s HB2; and priority local projects selected through regional competitions. The 55 percent reserved for the new project selection process is eligible to a broad range of projects, including roadway, public transportation, rail, operational improvements and transportation demand management projects and strategies.

Additionally, HB1887 shifts $40 million annually to public transportation projects from highway, aviation and ports, upping the commonwealth’s commitment to meeting the growing demand for public transit.

A more detailed story of Virginia’s funding legislation and subsequent reforms to the project selection process mentioned here can be found in our second Capital Ideas report from December 2015.

PROPOSAL #5

DIRECT MORE FUNDING TO LOCAL COMMUNITIES

Every state is required by federal law (Title 23 U.S. Code §134) to partner with urban and mid-size regions through entities known as metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs). These MPOs manage the planning, coordination, and administration of federal, state, and local funds that enhance the region’s transportation network for areas greater than 50,000 people. The theory of providing authority over federal funds for metropolitan regions is to move decision-making closer to taxpayers and ensure that their local priority projects receive funding, but reality is often far different.

In practice, due to the fact that state DOTs control the final list of projects that can receive federal funds (the Statewide Transportation Improvement Program or STIP), the state DOT can exert powerful influence to dictate how regional funds will be spent. Local communities need more control over and access to transportation funds than they currently possess.

Recognizing that the best decisions are often made by the level of government closest to the people, California reformed their transportation program in 1997 with the passage of SB 45. This bill preserved 25 percent of the state’s capital construction dollars for the State DOT (CalTrans) and directed the remaining 75 percent to local regions — giving them authority to determine how the funds would be spent. The bill also provided regional decision makers great autonomy in their planning and project selection process by requiring the statewide California Transportation Commission (CTC) to adopt all regional project lists into the STIP or reject all regional projects outright. This authority is not found in federal statute but is a step to which states are entitled.

CalTrans, with its capital construction dollars, focuses on maintaining the transportation infrastructure that connects the regions, while the funding directed to metropolitan regions provides them great authority over the regional transportation system’s development. California’s move to give funding and authority to metropolitan regions continues to be an important step to allowing regions to implement and effectively coordinate land use and transportation.

PROPOSAL #6

ENABLE LOCAL COMMUNITIES TO RAISE THEIR OWN FUNDING

Many transportation projects — especially the larger ones — typically require almost all levels of government to participate, requiring multiple stakeholders to combine a number of funding and financing sources. However, far too many states restrict the ability for locals to tax themselves to raise their own funds to support federal and state money, making it a challenge to put together the diverse funding streams required for many of these projects.

Without the ability to raise local funding, it’s also a challenge for local leaders to effectively compete for federal and state grant programs such as TIGER or New Starts that require matching funds. Debts have to be repaid and federal programs reward applicants with a strong local financial commitment.

Local communities want and need to put their own skin in the game, and states should enable them to do so. In recent years, a few state legislatures have moved to provide additional authority to raise new funding to local governments. In 2014, Indiana passed SB 16, which will allow six counties in the Indianapolis region to increase local income tax rates by between 0.1 percent and 0.25 percent and dedicate these additional revenues to public transportation. Governor Mike Pence understands full well the benefits of unleashing local investments in transportation:

“I am a firm believer in local control and the collective wisdom of the people of Indiana. Decisions on economic development and quality of life are best made at the local level. Whether local business tax reform or mass transit, I trust local leaders and residents to make the right decisions for their communities.”

Local voters will decide the fate of these tax increases via county voter referenda. SB 16 contains a provision to allow adjoining municipalities (i.e., cities and towns) to increase taxes and join the transit district by local referendum if the countywide vote in their county fails. The legislation also mandates that 25 percent of the transit system’s revenue be generated from fares and 10 percent of revenue is supported by business contributions through a non-profit organization. The law also prohibits funding from being used for any rail transit projects.

As part of Utah’s transportation funding package (HB 362) passed in 2015, counties were granted local option sales tax authority for multimodal investments in roads, transit, biking and walking infrastructure or almost any pressing local need — an option that will now be permanent, whether counties approved the tax or not in 2015. Of the 17 counties that chose to put measures on the November 2015 ballot, 10 were successful and will raise millions in new, flexible revenue that can be invested in local needs. Thanks to strong legislative support for public transportation funding, in counties with existing public transportation systems 40 percent of new sales tax revenue will go directly to transit. Those counties may see immediate improvements in service or planned expansions moving ahead.

Utah was one of three states profiled in our second Capital Ideas report which analyzed 2015’s progress in state transportation funding, published in December 2015. Download and read that detailed story.