Things DOTs say: “We have to preserve the level of service”

Why level of service (LOS) is the most important transportation measure that you’ve never heard of

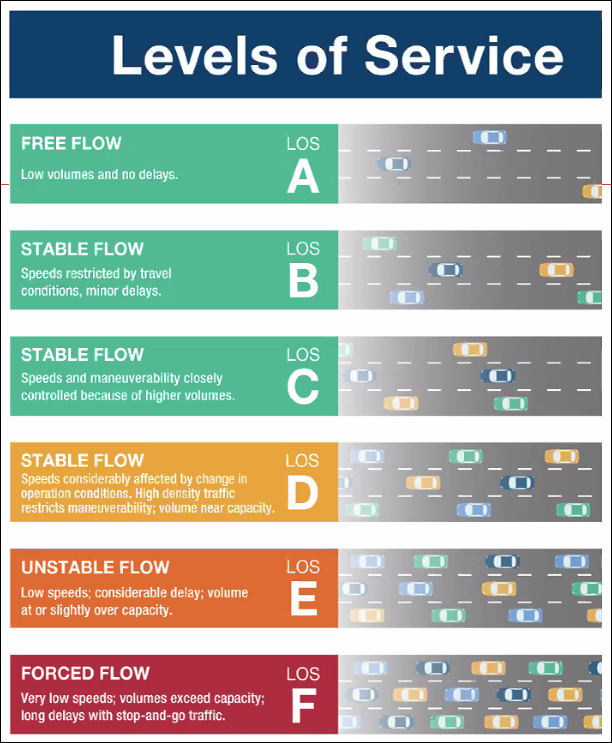

Level of service (LOS) measures a driver’s experience on the road and at intersections, based on the speed and number of cars using the road. The LOS of a road is designated by a letter grade of A (free flow) to F (near gridlock).

A designation of A, B, or C represents free-flowing conditions. F is stop-and-go traffic. These scores are based on the highest congestion level on that roadway, even if it only occurs a few minutes a day.

Why is LOS harmful?

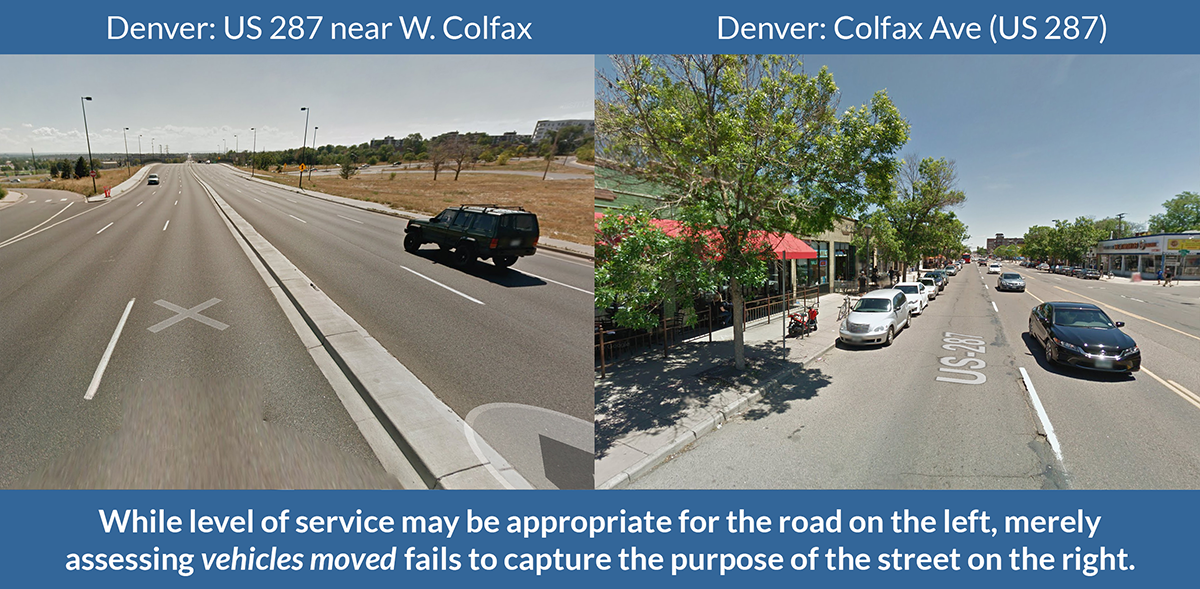

LOS is the primary transportation measure used by planners, engineers, and local officials when designing a roadway, considering changes to a roadway, or evaluating whether the roadway is functioning well. In zoning codes, LOS often takes priority over economic development, job creation, or housing.

Notice what is not measured in LOS:

- Transit users and people walking, biking, or rolling.

- Duration of congestion.

- Economic benefits of busy, if congested, retail areas.

- Economic costs of building-wide, sprawling roads for peak times.

- Tradeoffs of higher LOS, include safety risks, air pollution, heat islands, loss of habitat and trees, and housing displacement.

- Induced travel demand can wipe out the benefits of road widening in the long term.

Read more about the concept of induced demand in this more detailed T4America blog post.

Read more about the concept of induced demand in this more detailed T4America blog post.

Is LOS required?

No.

Transportation agencies at any level are not required to use level of service. There are no planning or project design requirements that mandate the use of LOS. States can adopt their own targets or use an alternative to LOS.

But the highly influential Green Book, which is written by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), adopted by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), compiling current practice for highway and street design—recommends LOS targets based on the roadway classification (eg, interstate, principal arterial, local, etc). And most then states adopt these targets into their design manuals.

State DOTs especially will insist that they are required to use level of service. This is not true, and FHWA issued a memo to officially explain that FHWA does not require any minimum LOS targets, that the Green Book targets can be unattainable, and that traffic forecasts are not the only factor that DOTs should consider.

Improvements and alternatives to LOS

If a DOT isn’t ready to move away from LOS altogether, they set more attainable goals. That might be allowing LOS-F on certain roadways in highly developed, economically robust areas or requiring LOS-E or F to occur for a certain period of time, such as over an hour a day, before it is defined as problematic.

The Office of the Secretary at USDOT has provided information on alternatives to LOS here. Those alternatives include:

- Multimodal LOS, which estimates vehicle, bus, bicycle, and pedestrian level of service on roadways but provides no way to consider which mode to prioritize when or how to make tradeoffs between the modes;

- Vehicle miles traveled, which looks at the number and length of car trips induced by development projects and transportation (the many benefits of this approach are beautifully explained by Streetlight Data here); and

- Person throughput, which is an analysis of how many people can move through a corridor whether they are in a car or not.

Better yet, DOTs could stop looking at vehicle movement as a proxy for whether people can get where they need to go and actually just measure that: multimodal access. With the wide availability of GIS since the 1990s, we can now determine how many jobs and essential services people can reach from their homes by all modes of travel. Vehicle movement and bottleneck relief is one way to improve that access but so is more frequent or direct transit service, safer roads for people walking or bicycling, and building services like groceries and retail closer to where people live. Virginia DOT has used this approach as a way to measure the benefit of potential transportation projects since 2015 (see the Smart Scale technical guide, page 69 and 95).

For more detail about how bad metrics like LOS lead to even worse outcomes, read this longer blog post from T4America:

Community Connectors: tools for advocates

You may be fighting against a freeway expansion. You may be trying to advance a Reconnecting Communities project to remove an old highway. You might be just trying to make wide, dangerous arterial roads a little safer for people to cross. This Community Connectors portal explains common terms, decodes the processes, clarifies the important actors, and inspires with helpful real-world stories.

You may be fighting against a freeway expansion. You may be trying to advance a Reconnecting Communities project to remove an old highway. You might be just trying to make wide, dangerous arterial roads a little safer for people to cross. This Community Connectors portal explains common terms, decodes the processes, clarifies the important actors, and inspires with helpful real-world stories.