Current state gasoline taxes aren’t enough to cover our transportation funding needs. Evaluating alternatives needs to involve taking five key principles into account. Read our policy evaluation framework, created by T4A Policy Associate Stephen Coleman Kenny with support from T4A Policy Director Benito Pérez, NRDC Senior Transportation Advocate Zak Accuardi, and T4A Policy Intern Julia Camacho.

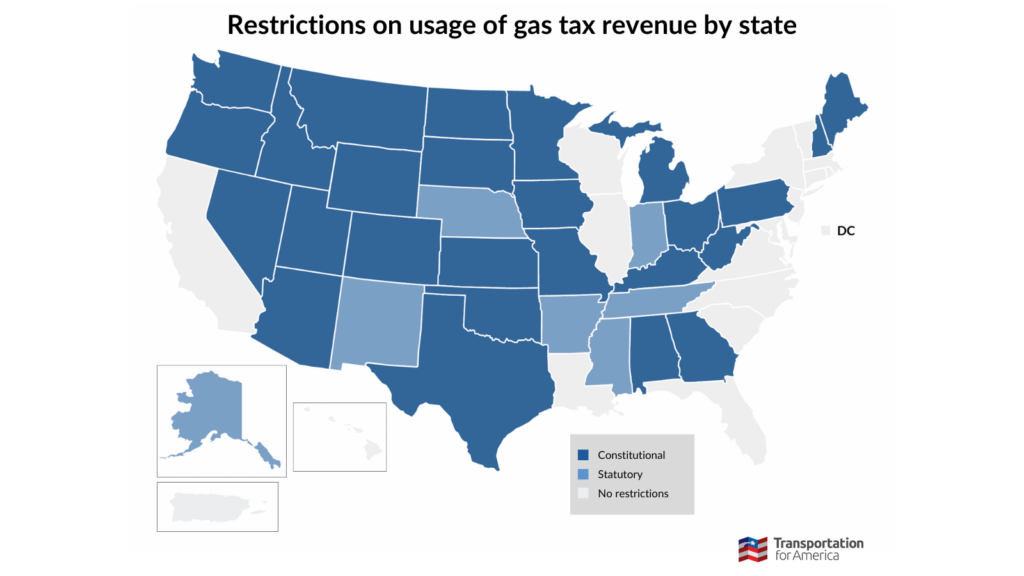

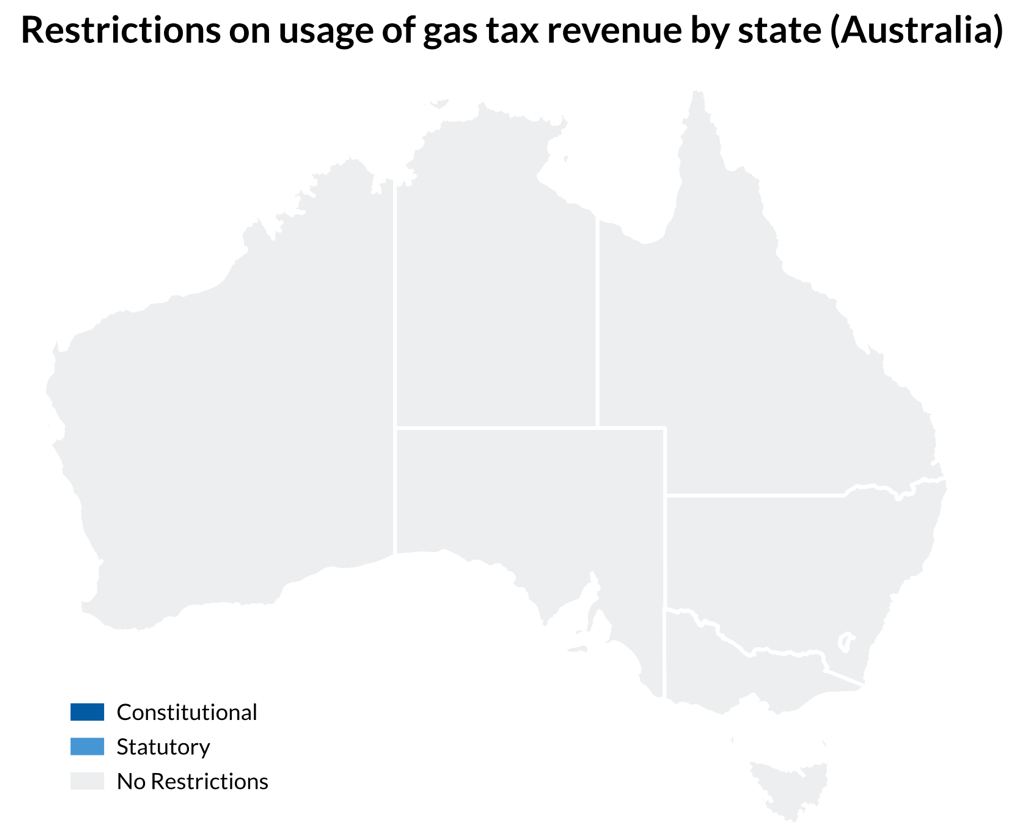

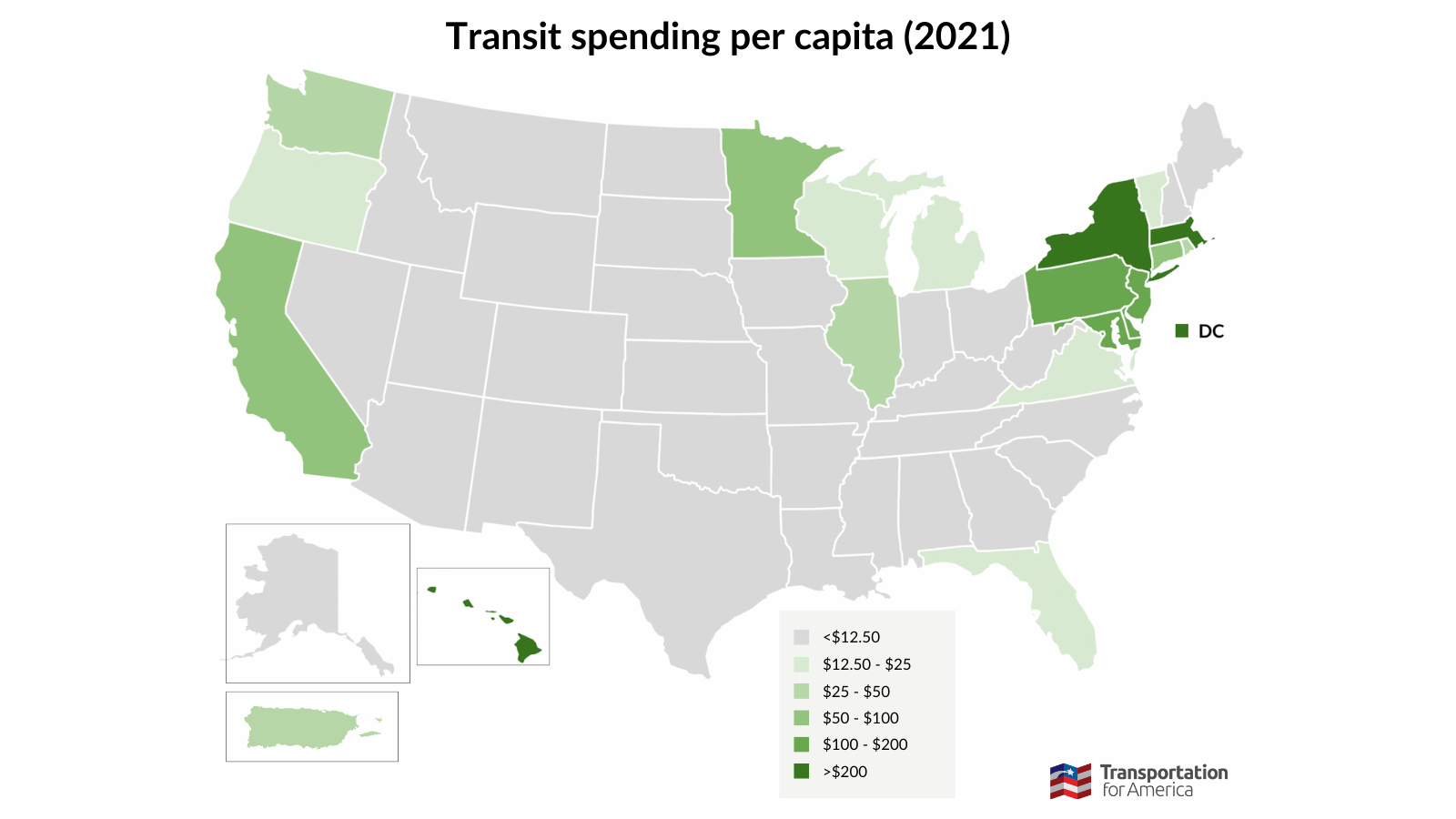

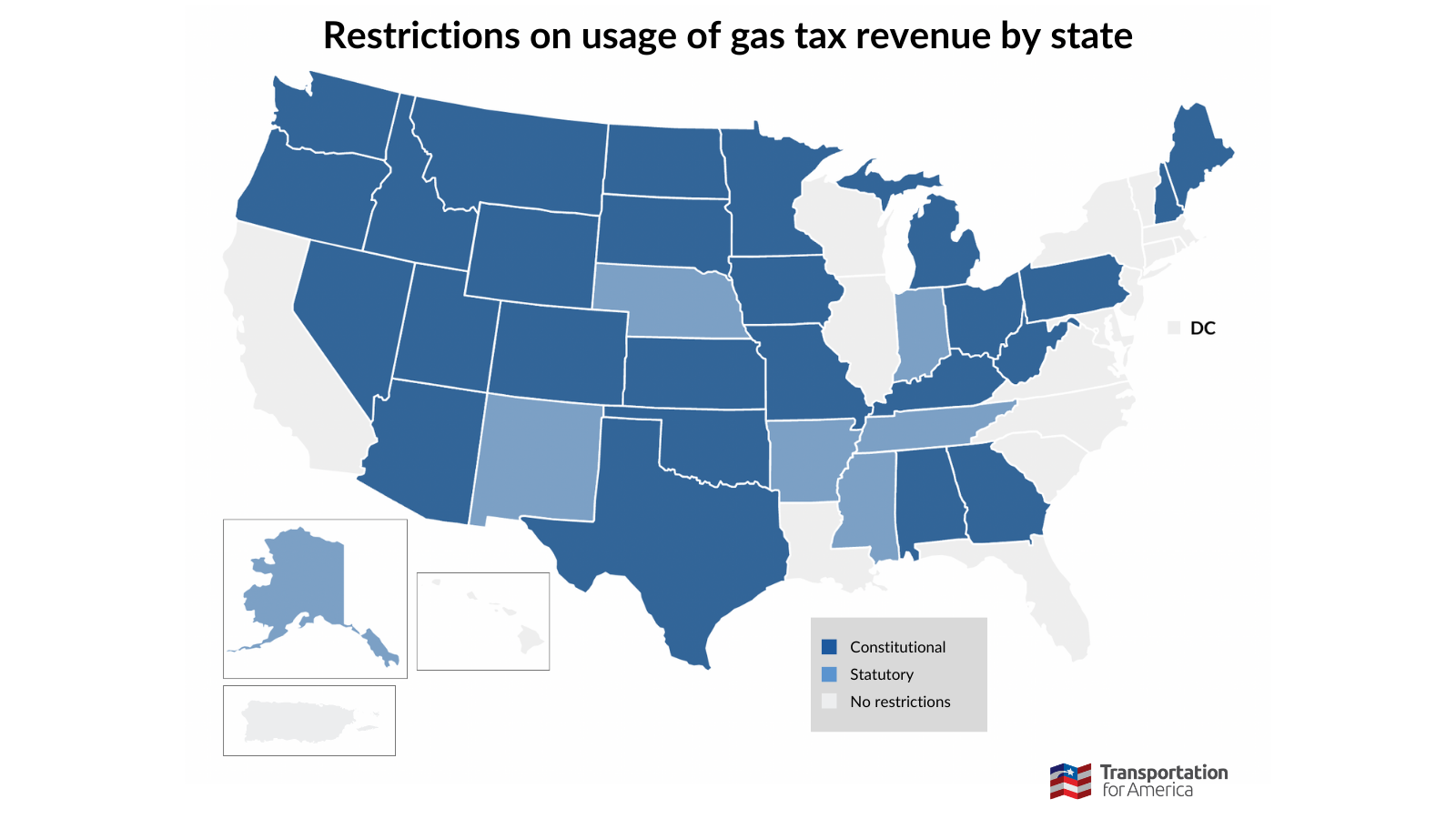

Our transportation systems are largely funded by motor fuel taxes that finance the federal Highway Trust Fund. Since the 1980s, these funds have been allocated using a roughly 80/20 split between highway and transit spending under the assumption that drivers were paying a larger share and deserved to receive more investments in return. However, after a crisis in 2008 when the national fund ran out of money—requiring billions of dollars in bailouts ever since—this system has proven to be outdated and unstable.

Why the gas tax status quo needs to change

In 2008, the National Surface Transportation Infrastructure Financing Commission wrote that the United States has an “ever-expanding backlog of investment needs” that then-current transportation funding policies would only cover one third of. As of 2016, public transit systems have faced a backlog of over $105 billion for maintenance and replacement costs.

Today, this problem is only worsening. America’s reliance on gasoline taxes in order to fund roads and transit systems is proving to be unsustainable. As vehicles become increasingly efficient and electric vehicles (EVs) become more commonplace, overall levels of fuel consumption are decreasing—thus lowering gas tax revenues and further widening the infrastructure funding gap. Without a change in our revenue-raising systems, our roads and transit infrastructure will crumble. It’s critical we act now.

As policymakers explore potential alternatives to the gas tax, a variety of options have emerged, including the following:

- Road pricing, or taxing by vehicle miles traveled (VMT)

- Adding new tolls

- Congestion pricing

- Flat vehicle registration fees

- Indexing the gas tax to inflation

- Taxes on external costs of driving like emissions and accidents

- General revenue subsidies

- Duties on fuel sales

Many of these proposals are not new—for instance, T4A wrote about raising the gas tax or indexing it to construction fees back in 2014. But save for some VMT-based road pricing pilot programs in Oregon, Virginia, and most recently Utah, little progress has been made.

Choosing the right option

There are a variety of possibilities, but no one option fits every regional context. Rather, the process of evaluation has to be sensitive to the goals and priorities of state and federal transportation programs. With that in mind, there are five main needs that new proposals will need to address, which we compiled into a policy evaluation framework:

- Outcomes: How the funding scheme changes road user behavior by incentivizing one of the following outcomes: electrification (EV adoption), mode shift away from personal vehicles, or maintaining the status quo.

- Fairness: Ensuring that the funding scheme is fair to all users by having road users (including drivers of internal combustion engine (ICE) cars and EVs alike) pay user fees in accordance with the wear and tear they impose on the road system.

- Stability: Estimating the revenue projections of the proposed system and whether or not it raises enough money to maintain the transportation system in both the short and long term.

- Equity: Examining how the structure of the funding scheme impacts different socioeconomic groups, and how the benefits and burdens are distributed.

- Feasibility: Considering the administrative costs, jurisdictional issues, technology for implementation, political popularity, and public support for the proposal.

There are tradeoffs between these goals, but looking at the possible alternatives to the gas tax through these five lenses provides a starting point for choosing a new policy. Find examples of our policy evaluation framework in action here.

Taking a closer look at a VMT tax and its implementation in Oregon

Among the options mentioned above, road pricing, or a tax on VMT, has emerged as a popular frontrunner among policymakers and thought leaders. A VMT tax would impact ICE cars and EVs equally, would include usage of all roads—not just interstates or toll roads—and would result in a precise user charge, especially if adjusted for vehicle weight, that drivers pay based on their wear and tear on the road system. However, the shortcomings of a VMT tax lie in the other four aspects—equity, outcomes, feasibility, and revenue stability.

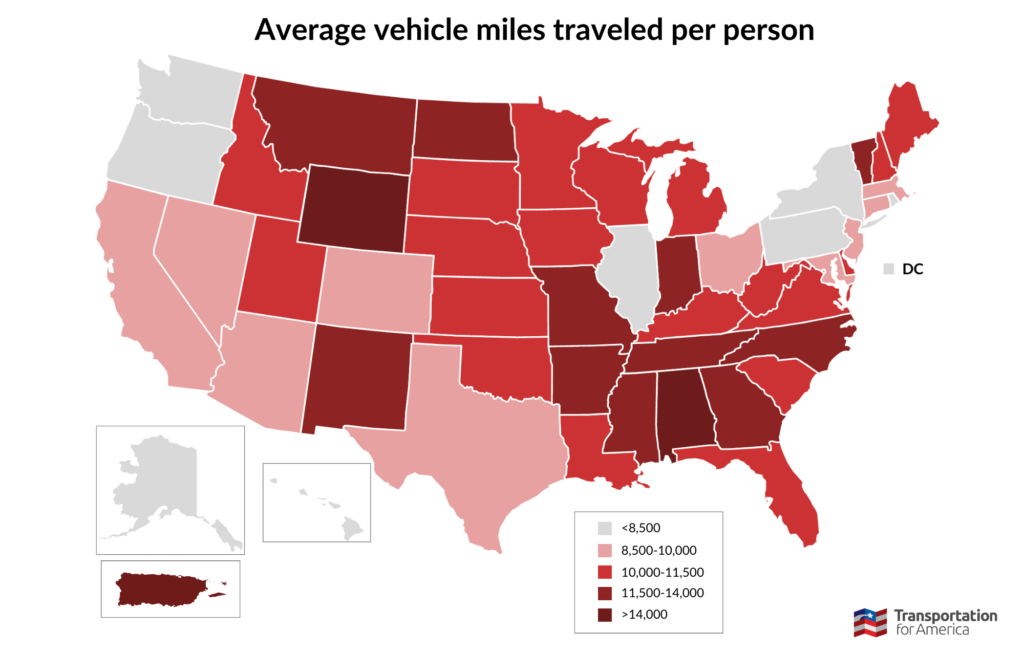

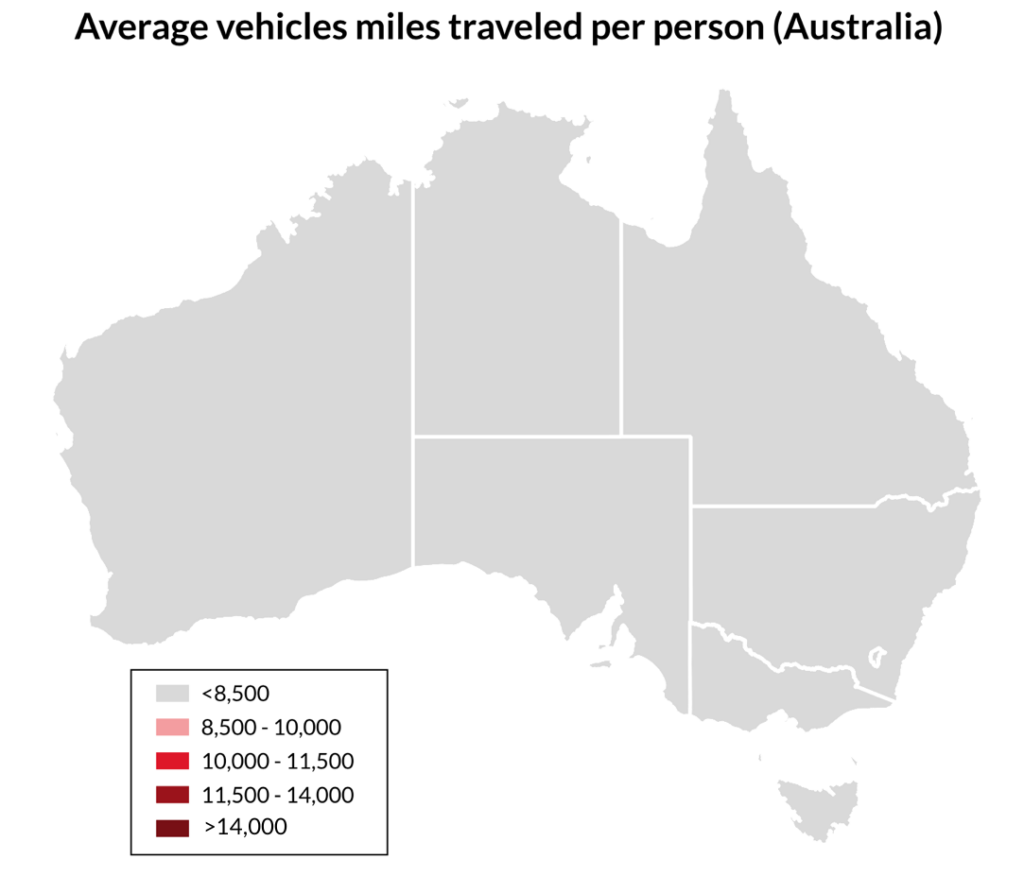

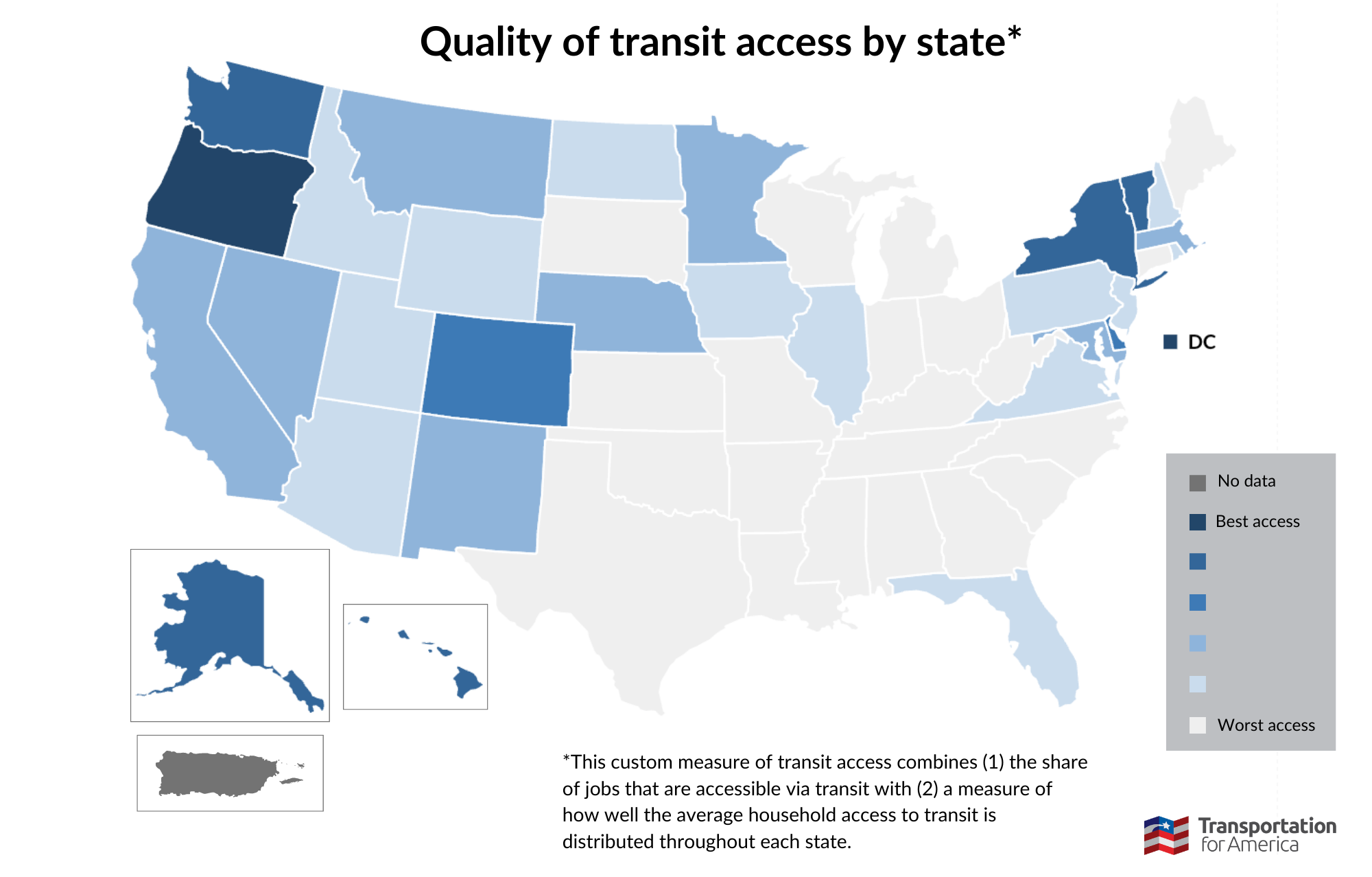

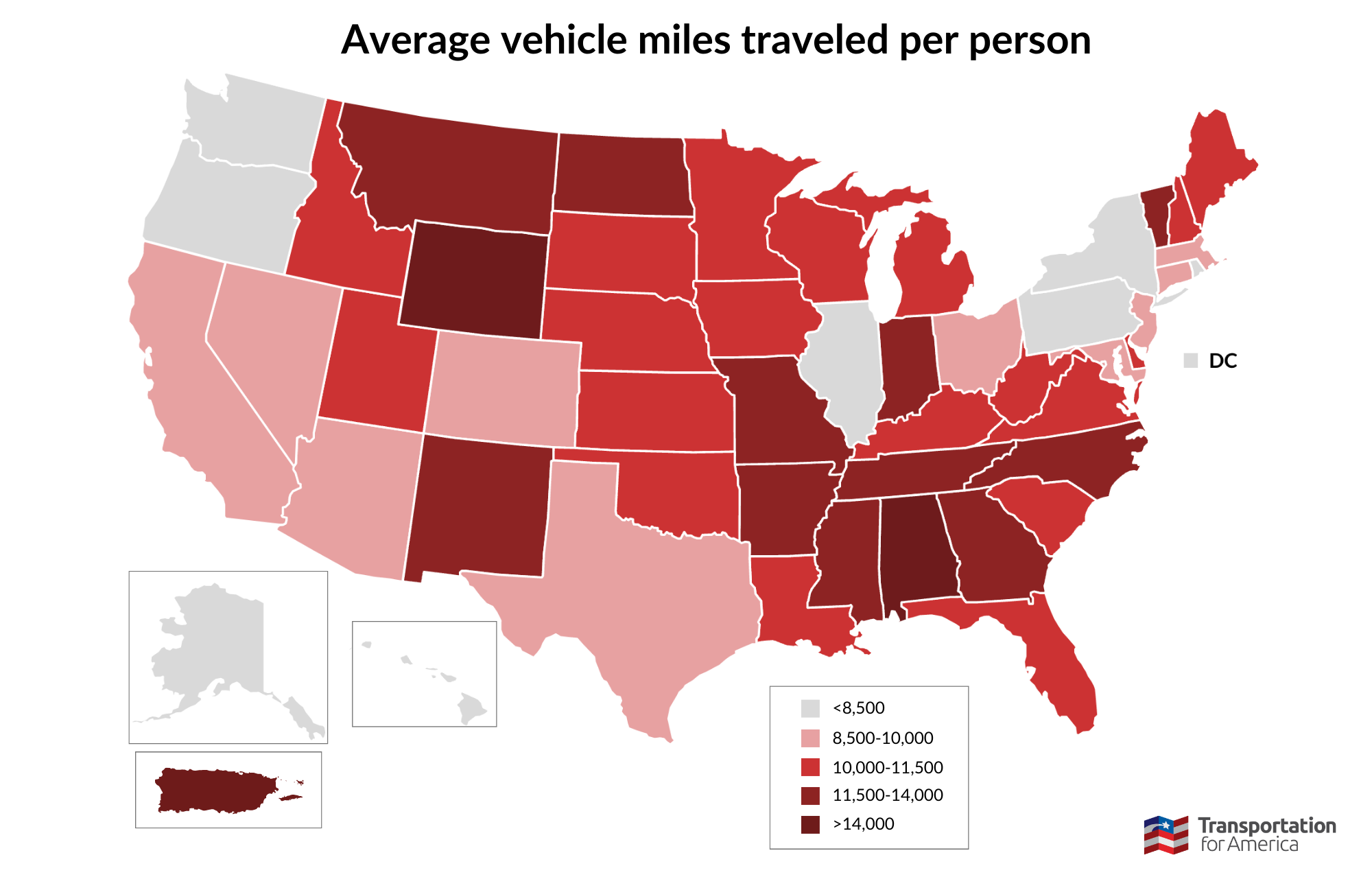

A VMT tax would be regressive, penalizing people who need to drive the furthest—in other words, rural households and those who live farther from city centers—and already have to pay high transportation costs as a result. Additionally, a VMT tax only incentivizes mode shift for that same group of people, who are the most likely to not be able to shift away from driving due to a lack of transportation alternatives.

Furthermore, a simple VMT tax doesn’t incentivize EV adoption over ICE cars or even just more efficient vehicles over heavier ones that use more fuel, since all vehicles are treated the same. With regards to feasibility, VMT taxes have faced technology challenges, high administrative costs, and public opposition. And in terms of revenue stability, a VMT tax is sufficient only if we maintain high levels of driving in the long term.

Oregon, a state that has historically been especially reliant on the gas tax for transportation funding, has tested out a VMT tax. In 2001, Oregon created a Road User Fee Task Force (RUFTF) in order to evaluate possible alternatives as hybrid vehicles and EVs began to rise in popularity. RUFTF decided to try implementing a road usage charge and launched a VMT pilot program in 2012 that succeeded in four areas: policy and public acceptance, technology, operations, and cost. This led to the creation of the voluntary OReGO program in 2015 that now enables drivers of EVs and efficient vehicles to pay a per-mile charge in exchange for reduced vehicle registration fees or gas tax rebates.

It’s notable that one of the aspects that wasn’t considered was outcomes—how the funding scheme changes (or doesn’t change) the behavior of road users, incentivizing electrification or mode shift or neither. Oregon’s eventual vision is to have a dual tax system—VMT for EVs and efficient vehicles, and a gas tax for all other vehicles.

When asked whether a VMT tax for fuel-efficient vehicles punishes drivers trying to do the right thing environmentally, Jim Whitty, who led the implementation of these programs at Oregon’s DOT, said that “making the great choice to buy a less polluting vehicle doesn’t make it a great choice to let the road system crumble.” And when asked why people who will pay more under a VMT system would volunteer to participate in the program, Whitty didn’t have a clear answer.

Notably, as of 2020, only 701 drivers were actively participating—well under the 5,000 that the program had initially envisioned. Oregon is now considering making OReGO into a mandatory policy, but other states should still try out other options before rushing to commit to a VMT tax.

Reevaluating America’s transportation funding systems

It’s of course critical that we act now to resolve this growing funding gap in order to address pressing maintenance needs and invest in the future of America’s transportation systems. When choosing an alternative policy (or combination of policies) to replace the current gas tax, it will be important to consider these five aspects—outcomes, fairness, stability, equity, and feasibility.

However, federal and state leadership will be as critical as funding. Both levels of government have a crucial role in transportation funding. Much innovation is fostered in localities, but without an overarching vision and approach, this can result in a patchwork of approaches that can spur inequitable outcomes.

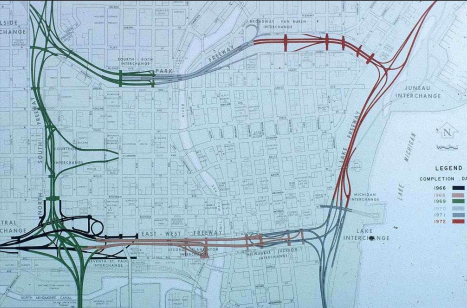

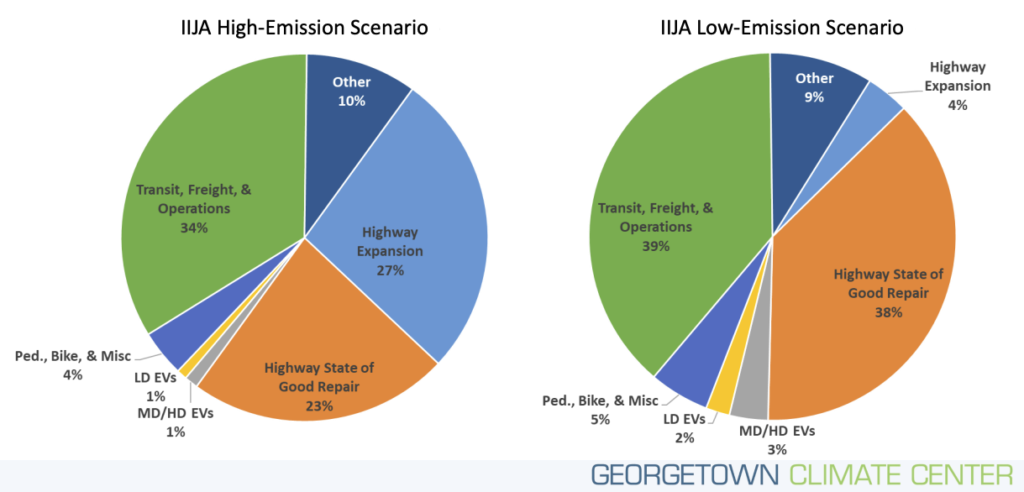

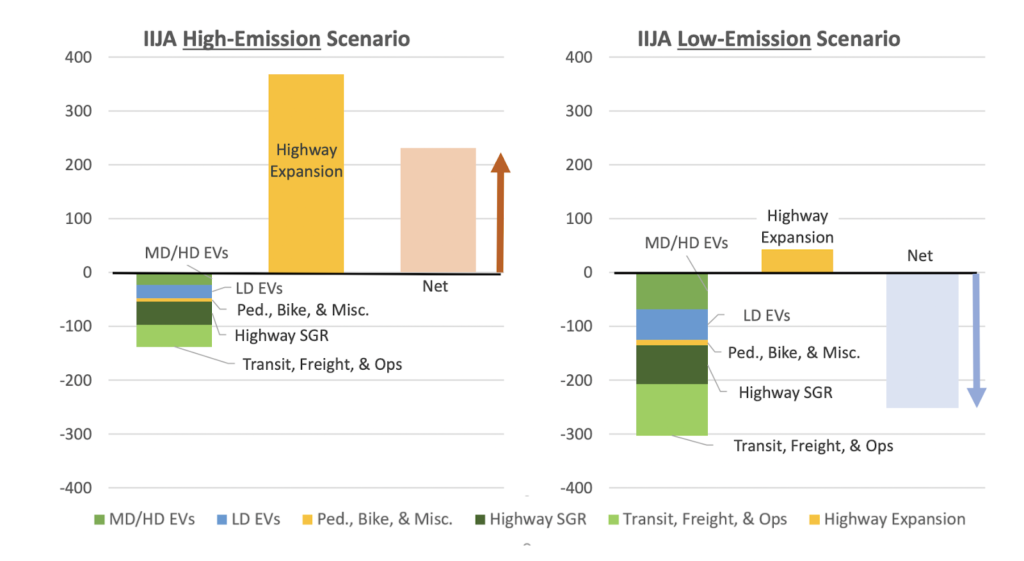

It’s also important that we consider the ultimate impacts of this transportation funding system: namely, how the money is actually used. In a foundational 2006 report on possible alternatives to the fuel tax, for example, the Transportation Research Board acknowledged that their analysis prioritized problems related to highway financing over public transit.

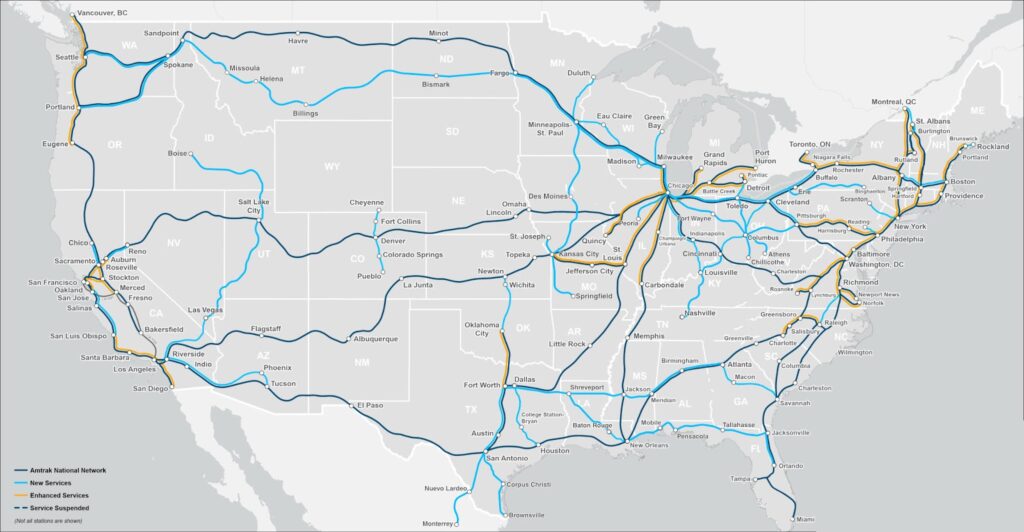

We can’t afford to pour money into expanding highways and worsening America’s transportation woes. Even if we achieve an optimal policy that maximizes revenue raised for transportation funding, we need to ensure that the money raised by any of these proposals is actually used for projects that prioritize maintenance and repair and make advancements towards reliable, affordable, and frequent transit systems that connect people to the places they need to go.

Learn more about how to evaluate alternatives. Read our policy evaluation framework here.