City and state budget deficits and a drastic decline in transit ridership have pushed transit agencies to the brink of collapse. Communities that were on the verge of expanding or building new transit may not be able to finance their projects if Congress doesn’t act.

Transit agencies across the country are facing huge operating and budget losses. While transit agencies are still operating to provide essential service, they are on track to lose billions this year due to revenue dwindling as a result of dramatically reduced ridership, increased cleaning costs, diminished local tax receipts, and other impacts from a contracting economy.

This has had a predictable impact on service, with every agency in the country making changes to reflect the drops in ridership. But also at risk are plans to expand or build new transit that have been in the works for years. These new services would yield significant mobility and economic benefits for communities in the years to come, but only if they can get off the ground.

Communities of all sizes apply to the federal Capital Investment Grants (CIG) program in order to secure federal funding for new or expanded transit projects—subway systems, commuter rail, light rail, streetcars, and bus rapid transit. Participating in the CIG program requires significant local political and financial commitment and years of dedicated work. But even with that comparatively high bar, there is still great demand for this funding, with over $23 billion in requests from projects currently waiting in the CIG “pipeline” for federal funding.

To access funding, Congress has recently required local communities to come up with at least 50 percent of the total cost, and under this administration, FTA has sought to make local communities pay even more. For many CIG projects, the local match comes from tax revenue and local community budgets. In many cases, communities have gone to the ballot to increase taxes to pay for these transit projects.

Now, all those carefully laid plans and contingencies could be for naught in light of the gaping hole that’s suddenly appeared in many municipal budgets—a 50 percent (or greater) local match could become an insurmountable challenge. Even projects that were on the verge of receiving a grant could see their “overall project rating” downgraded, which would prevent them from receiving a grant and delay critical projects which support jobs today, and long term economic development tomorrow.

Boosting CIG to create jobs

Back in March, Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Emergency Security (CARES) Act, a $2 trillion relief package that gives transit agencies $25 billion in emergency relief. While providing transit operating support, as the CARES Act did, will continue to be important to keep transit running and allow service to rebound as economies reopen, ensuring that capital projects receive adequate federal support will spur our economic recovery in the long run. Transit is a job creator, and investing in CIG projects means investing in jobs in local communities and in the manufacturing sector across the country. The supply chain for public transportation touches every corner of the country and employs thousands of Americans who produce tracks, seats, windows, communications equipment, wheels, and everything else in between. More than 2,000 manufacturing facilities and companies are tied directly to the manufacture or supply of new transit systems and repairs and upgrades to existing systems.

Every $1 billion invested in public transit creates more than 50,000 jobs and economic returns of $3.7 billion over 20 years. And during the 2009 stimulus, we found that dollar for dollar, “public transportation produced 70 percent more job hours” than funds spent on highways.

Further, access to transit has proven to be critical to economic development, and any long-term economic recovery will be nearly impossible without transit service to help people get back to work after this unprecedented crisis subsides. Companies of all sizes are relocating to or deciding to start up in walkable downtowns and communities with transit to ensure access to a high quality workforce. Communities designed around transit are desirable for workers and businesses, which will boost economic growth and support our economic recovery.

Investments in transit create jobs directly, and lay the foundation for long term economic prosperity.

What Congress can do

Congress has already stepped up to help transit agencies get through the beginning of this crisis by providing operating support in the CARES Act, and while transit agencies need additional operating support, we must also think about other important challenges facing transit.

To support local community demands for transit, and job creation today while supporting the conditions for job creation tomorrow, we need CIG, and to save CIG, Congress must:

- Provide no less than the FY19 funding level of $2.55 billion and $3.1527 billion in FY21 if Congress enacts the proposals below.

- Eliminate the local match for new CIG projects for projects that demonstrate an inability to cover the cost of the local match.

- Retroactively eliminate the local match for existing projects that demonstrate an inability to cover the cost of the local match.

- Prevent FTA from changing overall project ratings due to changes in local commitments or ridership projections.

A proposal for the long-term transportation reauthorization released by U.S. House Democrats on June 3 would address a number of these points, at least partially. There’s nearly $1 billion for emergency CIG support in the first year and a delay in payment for local matches. The bill would also allow a 30 percent increase in the federal share of project funding (for a total of up to 80 percent) for new projects and projects that received their grant as far back as 2017.

These actions would reduce strain on local community budgets, allow them to proceed with building transit, and give USDOT the resources to fund more projects. In the long-term, this would ensure more robust transit service and greater access to jobs and services. But in the short-term, it would create jobs and put Americans to work. It would allow projects to continue to move through the “pipeline” and eventually receive funding.

What transit agencies can do

As we wrote recently, transit agencies need to track and publicize how COVID-19 is impacting their agency. They should quantify the impacts of low ridership and of keeping service running for essential workers and document stories from personnel and riders to make the case for continued federal funding and local support.

Tell Congress what your agency needs and what your experience of waiting for CIG funds has been like. Congress needs to hear that there is continued demand for CIG funding and sustained local support to continue expanding transit.

And most importantly, continue to engage with local advocates and riders. Ask them to call their elected officials to explain how important transit is, and how transformational new or expanded transit in the community could be.

Current federal transportation policy is diametrically opposed to climate action. The Green New Deal framework released a year ago mostly left that unchanged. But a

Current federal transportation policy is diametrically opposed to climate action. The Green New Deal framework released a year ago mostly left that unchanged. But a

Rep. Garcia echoed this sentiment, saying, “It boils down to social justice. People cannot afford to get to where they need to go or stay where they grew up. We need to take a step back and start thinking about what it is we’re throwing hundreds of billions of dollars [at] every year.”

Rep. Garcia echoed this sentiment, saying, “It boils down to social justice. People cannot afford to get to where they need to go or stay where they grew up. We need to take a step back and start thinking about what it is we’re throwing hundreds of billions of dollars [at] every year.”

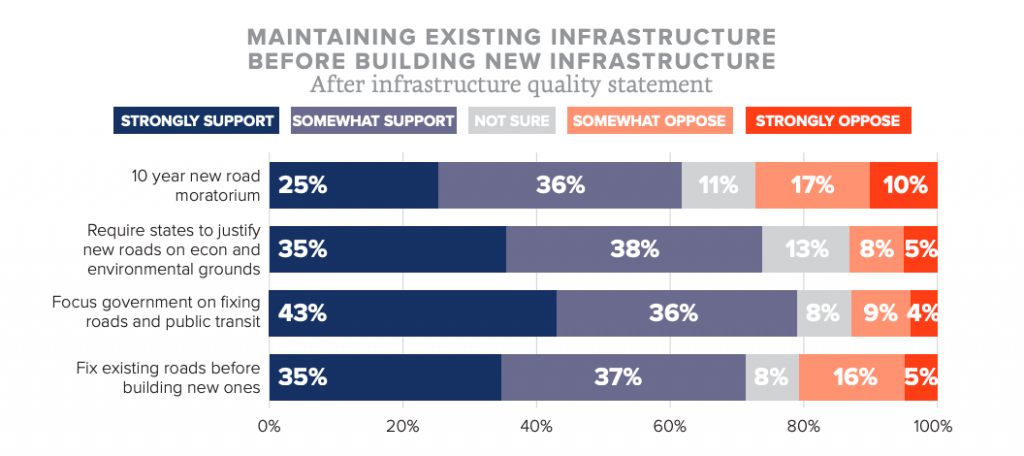

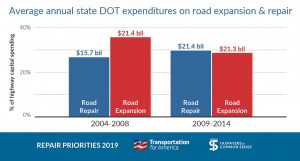

Politicians (and the media) love to bemoan our “crumbling roads and bridges.” That must mean we need more money to fix them, right? Here’s a secret: most of the billions we spend every year on our infrastructure

Politicians (and the media) love to bemoan our “crumbling roads and bridges.” That must mean we need more money to fix them, right? Here’s a secret: most of the billions we spend every year on our infrastructure