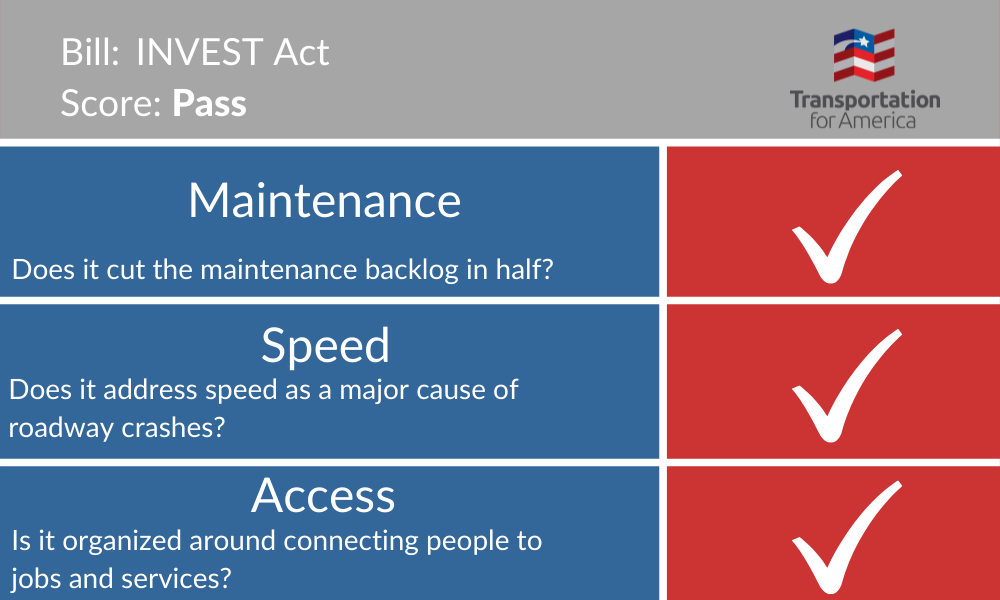

Update, June 29: This bill passed the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure (T&I) and will be voted on in the House of Representatives this week. A bipartisan amendment to fix the issues with the bill’s repair provisions was accepted by unanimous consent in the House (T&I) Committee. It’s our pleasure to change our scorecard below from 2/3 to a 3/3. We thank Chair Rep. Peter DeFazio, Rep. Jesús G. “Chuy” García, and Rep. Mike Gallagher for their tremendous support and leadership on this specific issue.

Federal transportation policy is in desperate need of an overhaul. This week, the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee released a bill that makes substantial changes to connect the program to outcomes that Americans value. Here’s more on how the House bill starts to redirect transportation policy toward maintaining the current system, protecting the safety of people on the roads, and getting people to jobs, schools, groceries and health care.

You can read our full statement about the bill here.

1) Takes steps to prioritize maintenance across the board

Prioritize maintenance is the first of our three simple core principles for federal investment in transportation. (Read more about all three here.) This bill doesn’t go as far as our specific call to cut the road, bridge, and transit maintenance backlog in half by dedicating formula dollars for maintenance, but it does push transportation agencies to prioritize maintenance in other concrete ways. Everyone in Congress talks nonstop about raising new money to “repair our crumbling roads and bridges,” and then they never make the requisite policy changes to guarantee it’ll ever happen. With this bill, the walk is starting to line up with the talk.

We should note that the overall highway funding in this bill is indeed growing overall, but we hope the language included in this proposal would lead to that money being spent in a different way. For one, 20 percent of the two biggest sources of state DOT highway funds are dedicated to bridge repair.1 For another, states will have to demonstrate three things before they can add new capacity with funds from the National Highway Performance Program, the largest highway program.2 DOTs would have to 1) demonstrate they are making progress on repair, 2) consider operational improvements and transit and show that expanding roadway capacity is more cost-effective than either, and 3) demonstrate that the expansion project would meet another performance target, like congestion reduction. This is a good step; however, this will only work if it’s matched with a strong standard to determine what defines “progress on repair” as well as a requirement that DOTs base their decisions and cost-effectiveness calculation on transportation models with a strong history of accuracy—and most currently do not.

Additionally, even if they fulfill these conditions above to add new capacity, there’s no language requiring the project sponsor to prove they can maintain the asset they are building, like we require transit project sponsors to do. That’s a big miss.

On the transit side, a new $600 million program is intended only for local transit projects which improve state of good repair (or other vital performance measures like emissions reduction, safety, or access.) There’s also a new formula program for keeping transit buses up to date that will always prioritize the agencies with the oldest buses, creating a rolling funding increase targeting the oldest buses as we try to modernize the nation’s transit fleet.

2) Institutes a comprehensive approach to safety

Designing for safety over speed is our second principle, with a call to save lives with road designs that support and encourage safer, slower driving. The conventional approach to designing highways—wide lanes and wide roads to allow for high speeds—has resulted in an epidemic of death on our nation’s roads and the highest number of people being struck and killed while walking and biking in three decades—disproportionately killing Black Americans and people in other communities of color. In this bill, safety goes from a talking point to action, focusing on making our roads safe for everyone and providing the money and standards for transportation agencies to build Complete Streets.

For starters, this proposal would take away the ability of state DOTs to set negative annual targets for safety. In other words, they can’t set a target for more people to die on their roads next year. Last year the National Complete Streets Coalition pointed out that not only were more people walking and biking being struck and killed by drivers in many states and they were 7 times more likely to be people of color, but many of those states were setting “safety targets” that assumed more people would die and there was nothing they could or would do to stem the tide. (Many “succeeded.”) The House bill should push those states to realize that there are things they can and must do in the design of their roadways to improve safety.

The proposal also dedicates more funding to protect the most vulnerable users and make communities more welcoming to pedestrians and bicyclists. This includes: 1) requiring states with the highest levels of pedestrian and bicyclist fatalities to set aside funds to address those safety needs;3 2) increasing Transportation Alternatives Program (TAP) funds by 60 percent from $850 million per year to an estimated $1.5 billion per year (which typically funds biking and walking projects); and 3) preventing states from transferring any of those TAP funds to other programs unless they make funds available to local governments who could identify no suitable projects. In a typical year, states transfer $150 million from this small program into the much larger highway programs.

There are also several provisions to embed safety into the planning and standards of transportation agencies. The bill would require FHWA to update its Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) to require speed limits to be set with a consideration of the community surrounding the corridor, the number of bicyclists and pedestrians, and crash statistics (as opposed to just traffic conditions). Right now, speed limits are set by how people behave; so if you build a wide street and people drive too fast, the speed limit is often raised to accommodate the rule breakers. States would also be allowed to use various funds to create plans for Complete Streets and Vision Zero plans—an effort to completely eliminate traffic fatalities, in part through street design. Finally, the bill would require each state to conduct a vulnerable road user safety assessment as part of its strategic highway safety plan.

This bill is markedly different than its predecessors and if enacted it will most certainly create a safer transportation system and save lives.

3) States and metro area planners must determine how well their system connects people to jobs—drivers and non-drivers alike

Our third principle is measuring transportation success by how many jobs and services people can access, not how fast cars can drive on specific segments of road, as our current program does. If the goal of transportation spending is to connect people to jobs and services, then that must be measured and considered when funding decisions are made.

Access to technology like GIS and cloud computing allows us to now measure travel by all modes from residential areas to jobs and services. With this information, we can consider all kinds of transportation projects and all transportation users equally. We can also see when it is more cost-efficient to build the things people need closer to them, rather than defaulting to building more transportation projects to make far away necessities less inconvenient to travel to.

This is where this bill most hits the mark. For the first time at the national level, recipients of federal transportation funding will be required to measure how well their system connects people to the things they need, whether they drive, take transit, walk or bike. Right now, the program assumes if vehicle traffic is moving that trips are easy and access is high. This ignores those who can’t or don’t drive, which are much more likely to be those who are low-income, people of color, or those who are mobility-impaired. Under the House bill, state DOTs and MPOs must consider whether people traveling (not just driving) can reach jobs, schools, groceries, medical care and other necessities. And they will be penalized if they fail to use federal funding to improve that access.

Additionally, the House proposal creates an Office of Transit-Supportive Communities within the Federal Transit Administration to provide funding, technical assistance, and coordination of transit and housing projects within the USDOT and across the federal government. Putting housing (and especially attainable housing) close to transit is a powerful way to increase access to jobs and necessities. Further, this proposal adds affordable housing into the planning considerations for MPO and state DOT Transportation Improvement Programs, as well as for future transit capital grants. Through this legislation, the House authors recognize the connection between transportation, housing and development and propose bringing them together in federal policy and investments.

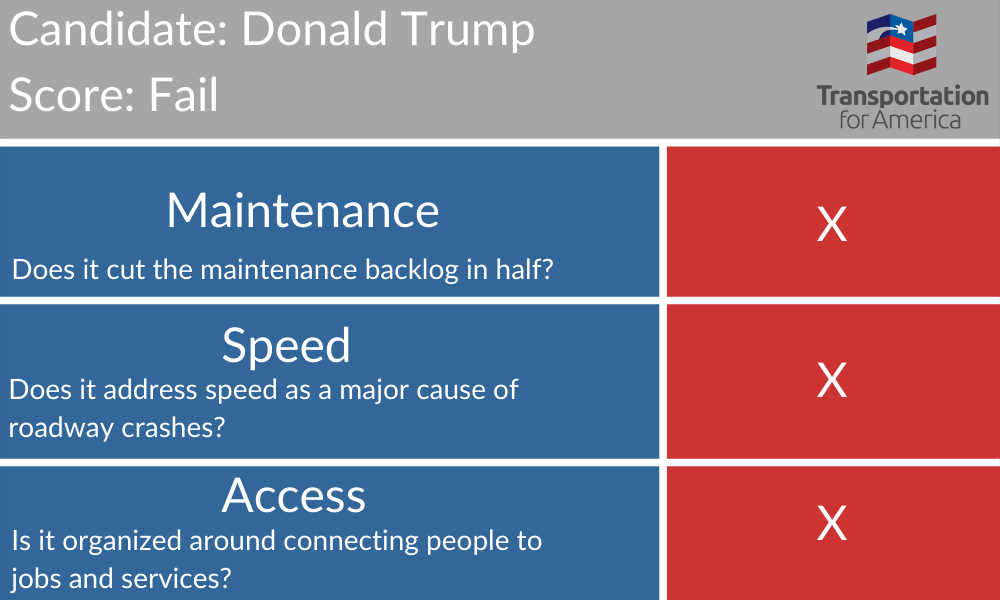

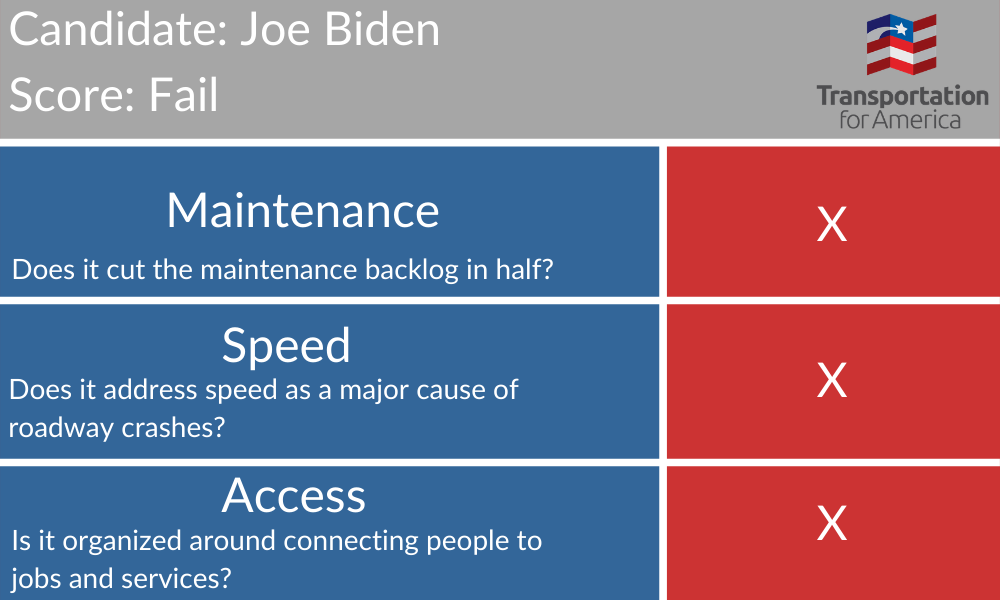

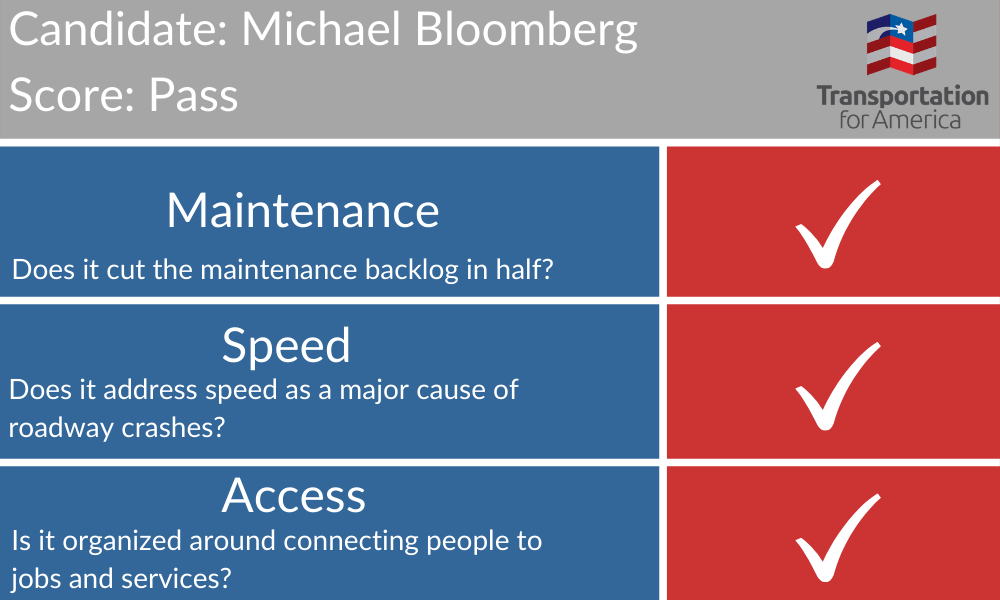

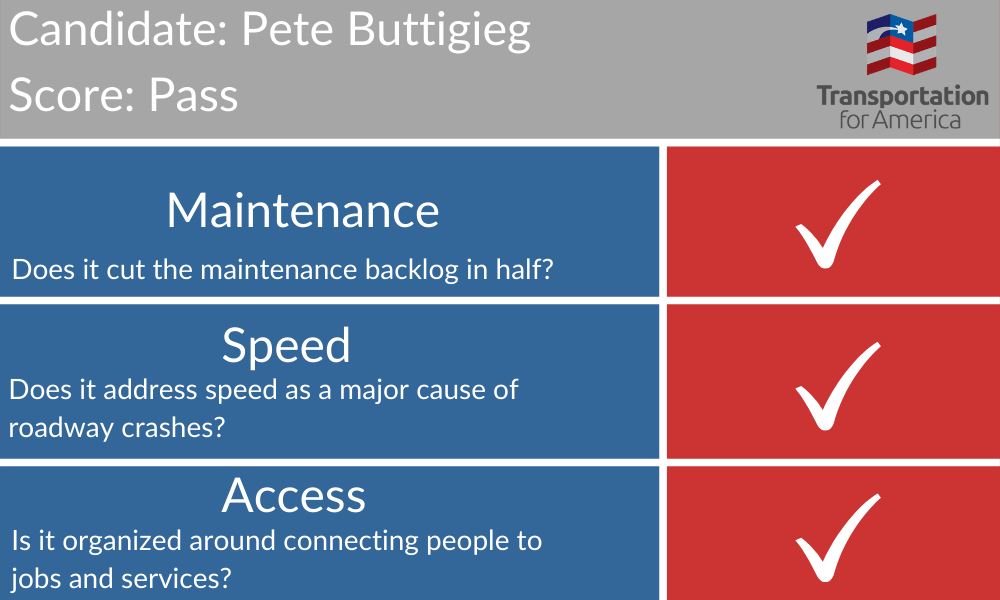

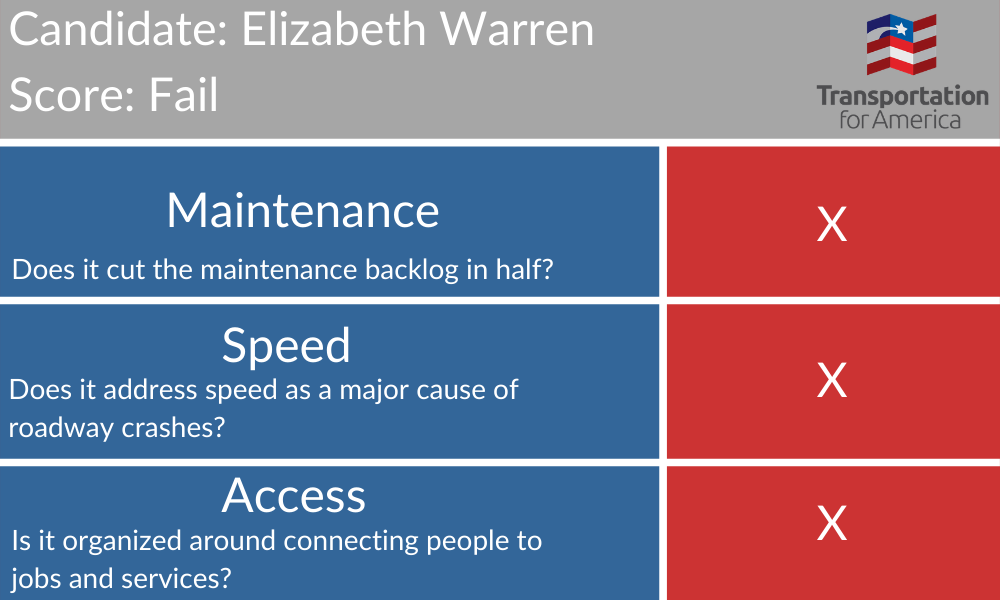

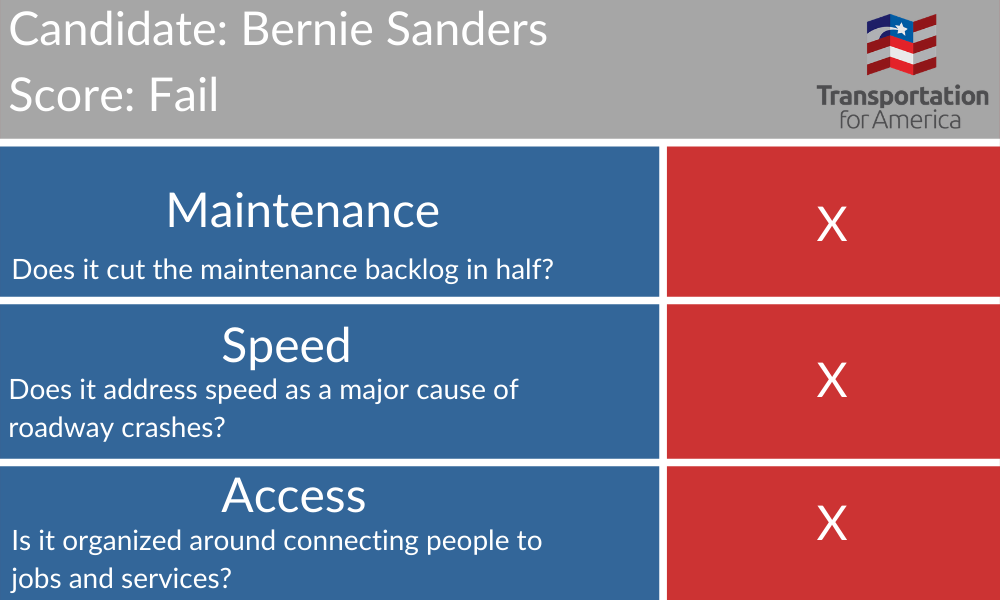

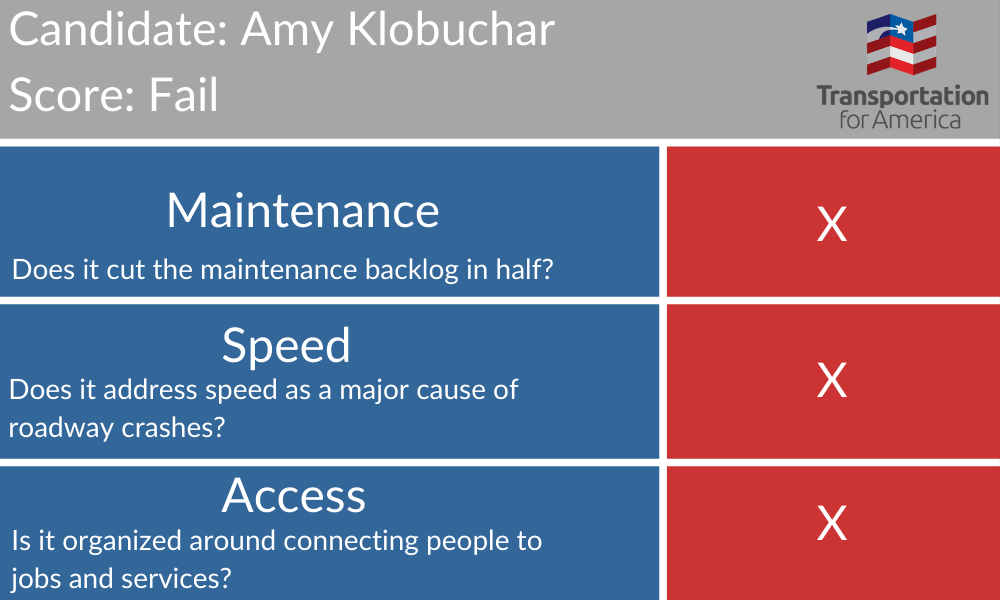

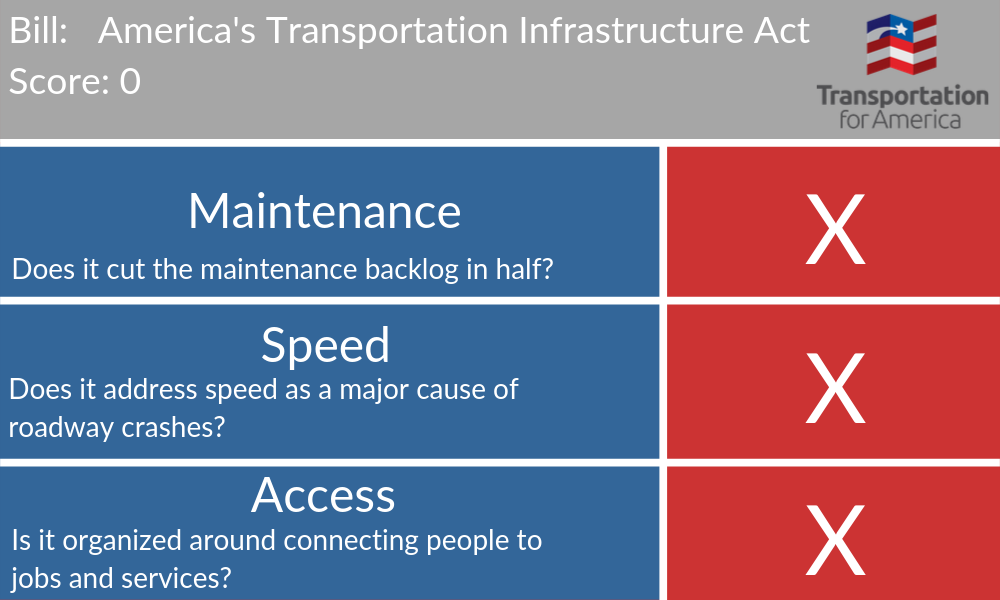

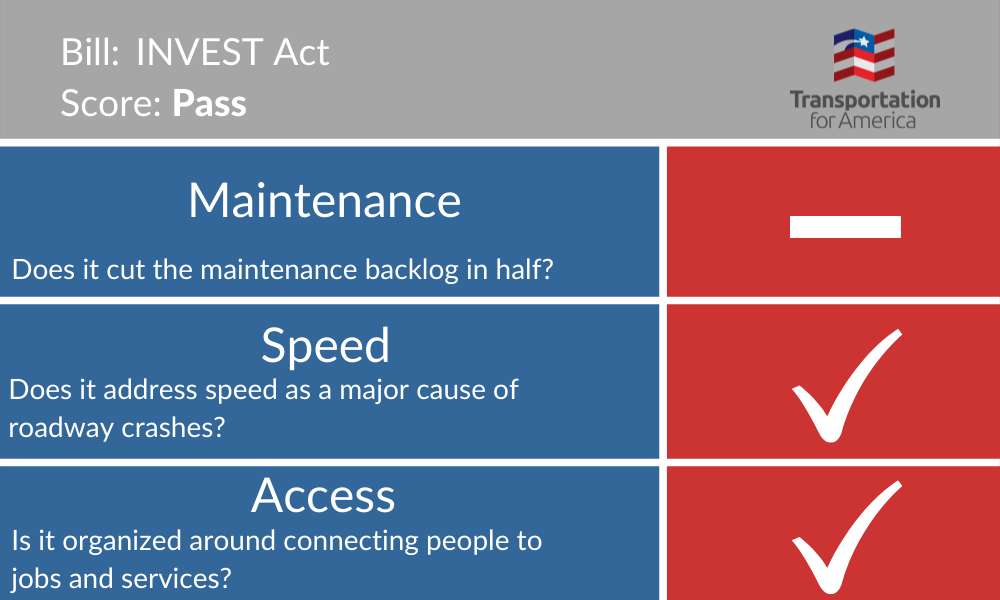

The score:

The INVEST Act checks two of the three boxes in our scorecard, but especially access and safety where the authors showed real comprehension of the problems and innovation on the solutions. On repair, the final verdict will be decided in the regulatory work that is done by USDOT, which is not ideal. We strongly recommend that the House strengthen their language on repair to ensure that we don’t end up with a much larger overall program with the same problem as before: neglected maintenance needs while states find creative ways to continue building things they can’t afford to maintain. On the whole, we’re glad to see the House move the program in a new direction, which is a vast improvement over the current proposal from the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, which got an “F” for their costly status quo approach.

Learn more: Read our follow-up post that delves into nine other (mostly positive) things to note about this bill.