USDOT has released its Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) for the FY2025 round of the Safe Streets and Roads (SS4A) competitive grant program. Almost $1 billion is available for projects that improve roadway safety for people in and out of a vehicle.

SS4A grants are open to Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs), Tribes, municipalities, counties, or business improvement districts for projects to enhance roadway safety. Unlike previous years, transit agencies that aren’t created by state authority are no longer eligible to apply.

Of the available funding, $580 million is intended for implementation grants, while $402.3 million (or 40 percent) is set aside for planning and demonstration grants. Applicants can seek planning funds for road safety action plans, supplemental planning, or quick-build demonstration projects. If they already have a safety action plan, applicants must submit a self-certification eligibility worksheet by email no later than May 9, 2025 (5 p.m. ET). Applications for planning and demonstration grants and implementation grants must be submitted by June 26, 2025 (5 P.M. ET).

The USDOT’s R.O.U.T.E.S. grant toolkit is available to support communities that may need technical assistance in navigating the grant application process. This toolkit is intended to ease the burden for communities, particularly rural or underserved, by providing information on competitive grant opportunities and strategies for putting together a successful application.

What’s changed?

Despite similarities to previous SS4A NOFOs, there are some notable changes that reflect the priorities of the current Presidential administration.

One of the main updates is to the selection criteria section. Economic competitiveness, equity considerations, workforce, and the climate are no longer included. Additionally, projects that reduce lane capacity for vehicles will be viewed less favorably by the administration. Applicants who have not previously received funding from this program will be favored for both planning and implementation grants. To apply for an Implementation grant, applications must certify that they have a recent and valid safety action plan. The components required for a valid safety action plan can now be found in up to three plans recently developed by the applicant. Examples of plans that could be eligible are a local Vision Zero plan or a regional transportation safety plan. The plans must be developed between 2020 and June 26, 2025.

Big opportunity to test roadway change

The SS4A program offers a valuable opportunity for cities, towns, and counties to test roadway changes through quick-build demonstration projects. These temporary, low-cost interventions allow communities to experiment with new street designs, such as bike lanes and safer crosswalks, before making permanent changes.

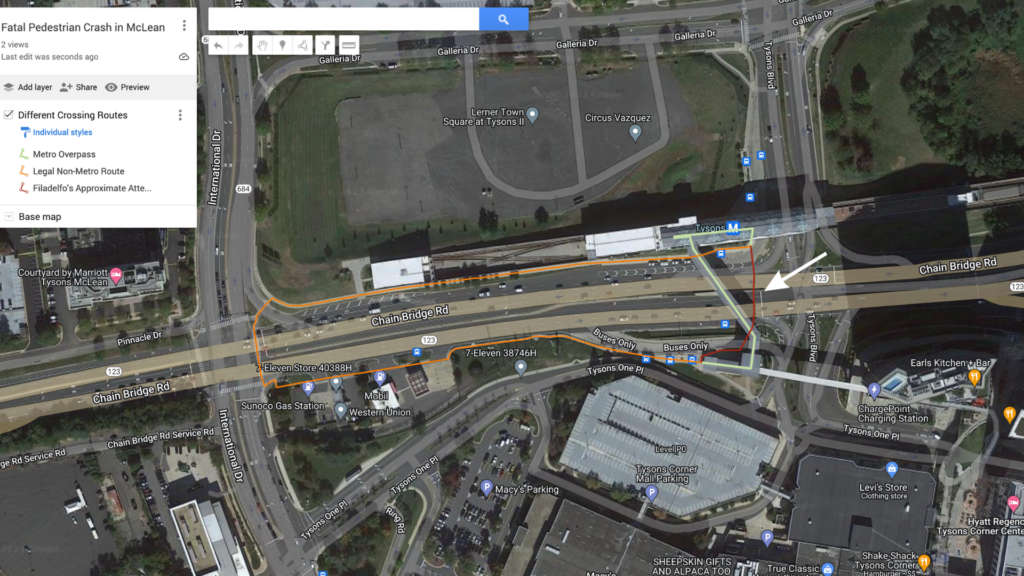

By testing these improvements, communities can gather feedback, measure the safety impact of the design intervention, and address concerns in real time. Piloting street design changes quickly and cost-effectively can help build valuable momentum towards long-term safety improvements. This was the case in Versailles, Kentucky, which secured an SS4A grant to fund quick-build demonstrations to inform updates to their Regional Safety Action Plan. Temporary installations were implemented to measure the impact of design changes on high-crash areas, and the lessons learned from these projects will guide long-term improvements to these areas and other locations across the county.

Tips for writing a great grant application

SS4A is an important tool to advance roadway safety for all users. That’s why we believe it’s crucial that communities of all sizes capitalize on this opportunity. While there will be scores of competitive applications, we’ve compiled some key strategies that will better position applicants to win these grants:

- Communities must align their project objectives with the program criteria. Tailoring projects to meet the program criteria included in the notice of funding opportunity ensures their project is eligible for the program. A competitive application will clearly define the problem the community is facing and specify how the project will address those needs.

- Build a diverse coalition of stakeholders, including local leaders and businesses, to demonstrate a broad base of support. Competitive grant programs often require a certain amount of non-federal funding to match the federal dollars. A wide array of supporters can help put together a local match, which can even include in-kind contributions. Additionally, understanding the specific funding program parameters and administrative steps is essential for having a better chance at success.

- Preparation is key. Start the process early, and stay informed through webinars listed by the NOFO to get an overview of the opportunity, ask questions, and effectively coordinate your application to ensure your project stands out.

Now is the time to prepare your SS4A Application

SS4A funding can help communities design safer, more connected streets for everyone who uses them. With SS4A applications due by June 26, 2025, cities, towns, counties, or other metro areas interested in pursuing a grant should start planning now to put together a strong, competitive application.