A leaked policy memo from leadership at USDOT will add a new layer of extra-legal review of all awarded competitive grant projects without fully signed federal funding obligations, calling for bicycle infrastructure, green infrastructure, and EV chargers to be cut from projects.

What’s in USDOT’s new memo?

Drawing authority from the President’s inaugural slate of executive orders and the Secretary of Transportation’s first round of policy memos, the Department of Transportation Secretary’s office has, according to a leaked policy memo, issued another round of unprecedented orders, calling for the removal of all elements of projects related to bike infrastructure, charging infrastructure, climate change or those that take equity into account competitive grant funding. The memo specifically applies to competitive grants that have not yet completed grant agreements or obligated the funding, including those that have only been partially obligated. Projects with existing and executed grant agreements are not subject to additional review, but any new federal dollars made out to those projects would be.

What’s the difference between funding that is announced or obligated?

When the federal government announces an award, the awardee does not get that funding as a grant. First, the federal government and the awardee have to negotiate and sign a funding agreement, which lays out the project scope, schedule, and budget and demonstrates the availability of required nonfederal funding match.

Funds can be canceled or reclaimed until they are obligated, which is a binding commitment to pay out money. Funding cannot be obligated until the grant agreement is signed and all permitting and relevant regulations are complied with. Planning grants that don’t have those regulatory requirements are obligated once there is a signed grant agreement. However, capital (ie, construction) projects would need to complete regulatory review and permitting before being obligated.

Once there is a grant agreement and funds are obligated, an awardee must spend their own funding and file for reimbursement from the federal government.

This memo instructs USDOT operating administrations, like The Federal Transit Administration (FTA) and The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), to conduct a project-by-project analysis to identify any activities that include primary elements of “equity, climate change, environmental justice, green infrastructure, bicycle infrastructure, electric vehicles, and charging infrastructure.” Once projects are identified for non-compliance with the administration’s priorities, they will be subject to individual scrutiny for a final decision on whether they will be canceled, modified, or continue as planned. Projects that contain “flagged activities” could be revised, even if they meet all requirements of law, to comply with this administration’s agenda. This comes full circle from the “Woke Rescission” memo, which we unpacked in a previous blog, and follows the episode of STIP and TIP review of obligated projects that were recently walked back (though the new burdensome review remains an issue for environmental permits, according to a recent letter from AASHTO).

While it is normal for a new administration to set its own agenda, it has always applied to spending and policy going forward. This administration is setting the precedent that any project not underway can be undone when there is a new president. This memo furthers the agenda laid out in the “Unleashing American Energy” memo, which calls for increased reliance on fossil fuel consumption.

Under this approach, USDOT will reach back to 2022 to defund many projects that Congress specifically defined as eligible activities in the text of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Congress defines the scope of what federal programs can fund. Even under the Biden administration—despite its commitments to advancing zero-emission transportation—USDOT still followed congressional intent by awarding the statutorily required 25% of funds to more emitting fossil fuel buses under the Low or No Emission bus program, despite strong demand for zero-emission buses from applicants.

By nature of being eligible for funding, the bike, green infrastructure, and EV chargers elements of projects already got the okay for funding from Congress on a bipartisan basis. If this becomes precedent, future presidents could make unilateral decisions to freeze funding for any project that does not align with their own priorities. Allowing the pendulum to swing back and forth every four years undermines the rationale of the supposedly stable highway trust fund—perhaps further evidence that the model is no longer sustainable. If funding appropriated years in advance can be arbitrarily revoked, why even plan beyond the next fiscal year?

For an administration that has spoken at length about the elimination of waste, fraud, and abuse, even absent the hugely dangerous and detrimental impact this will have on people’s health, safety, and long-term environmental sustainability of the transportation system, these reviews are going to slow down projects they would want to proceed. Actions like these continue to sow confusion and are inefficient, waste staff time, and squander funds and resources at the federal and local levels.

What’s at stake

Nearly $2.9 billion in funding was announced for the Safe Streets and Roads for All grant program for projects in over 1,700 communities. Only $515 million has been obligated across 979 grant,s according to a search of USASpending data. The vast majority of this program’s funding, $2.4 billion, and hundreds of communities receiving assistance through this program would now be subject to review and renegotiation due to this memo.

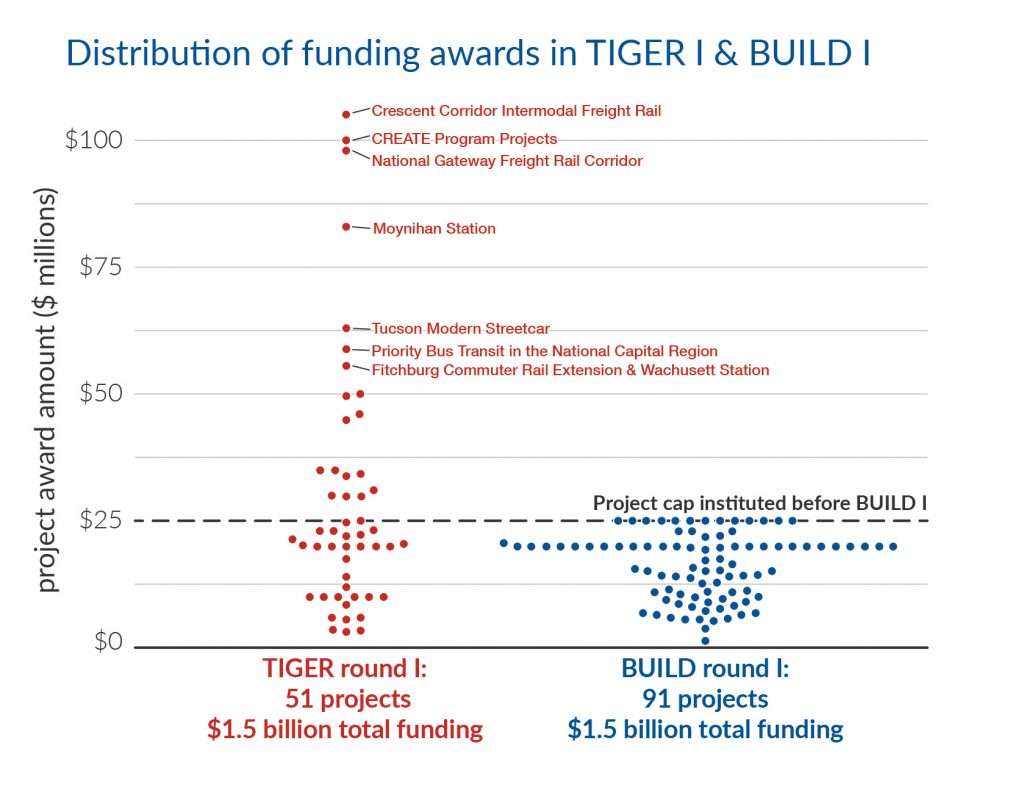

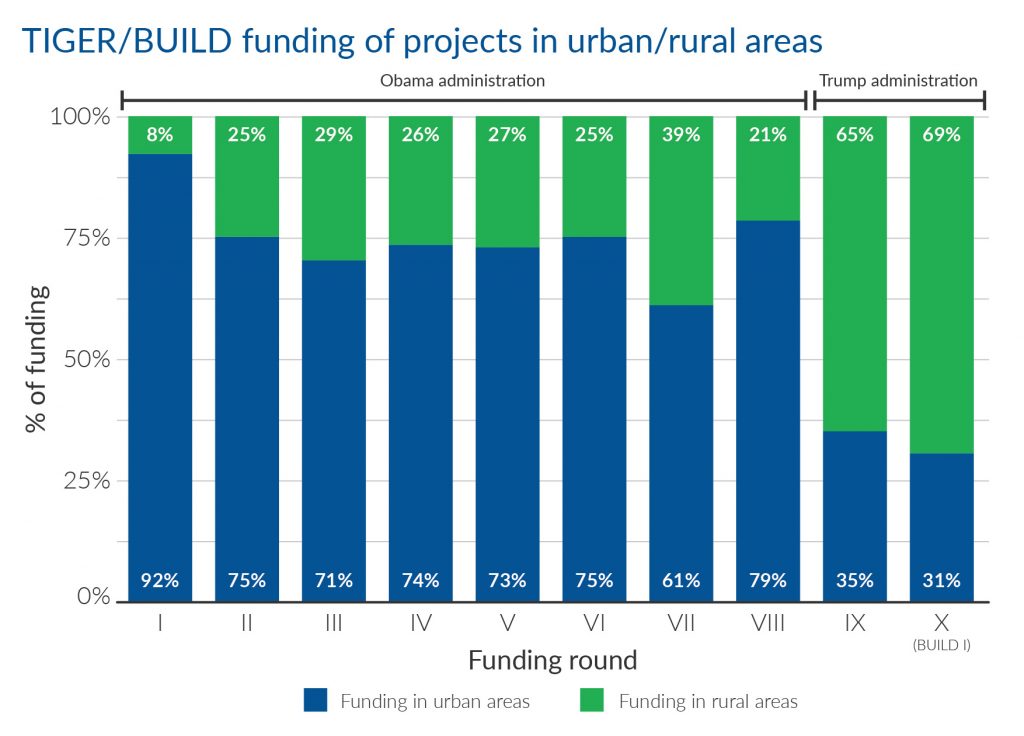

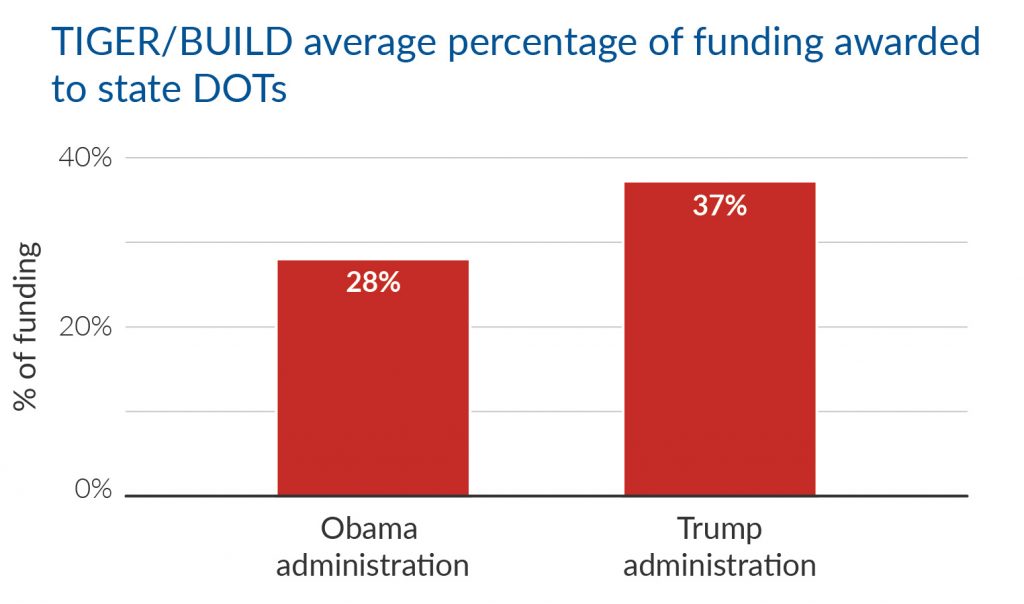

About $7.6 billion was announced under the RAISE/BUILD program for federal fiscal years 2022 through 2025. Still, only $1.25 billion, or less, of funding has been secured and obligated, leaving the rest of the announced funds, representing potentially hundreds of projects, stuck once again in the grant review process.

Zooming out to the whole program, based on data last updated by the USDOT on January 31, the Federal Highway Administration, the Federal Transit Administration, and the Federal Railroad Administration have a combined $51 billion in funds unobligated for non-formula programs. Much of these funds are now likely subject to review, cuts, and delays.

It likely will not stop there

While the current memo applies to competitive grants, there is good reason to expect that this administration will expand this review to cover other programs, too, if they find they don’t agree with how states, regions, localities, and transit agencies are using the funds.

For example, new, flexible formula programs created in the IIJA designed to address infrastructure resiliency, greenhouse gas emissions from transportation, and build out the national network of electric vehicle infrastructure remain at risk and could be the next target for politicized review and freezes. Further, if Congress decides to rescind funds for impounded or frozen climate-related programs, the impacts would disproportionately hit rural states, likely disrupting planned projects of all types. Carbon Reduction Program and PROTECT funds have been programmed for anything from new highway lighting to tunnel rehabilitation. Members of Congress should be aware of how cuts to these programs may fall hardest on whose constituents.