Lawmakers in Nevada have recently introduced legislation to set aside Carbon Reduction Program funds—about $3.9 million per year—for medium- and heavy-duty vehicle (MHDV) electrification. Although MHDV electrification is essential, assembly bill AB184’s method for doing so is inefficient, ineffective, and unnecessarily generous to private actors at the expense of taxpayers.

When the 2021 infrastructure law was passed, it included a number of new formula and competitive transportation programs. The focus of these funds ranged from culverts and wildlife crossings to set-asides for state and regional level Complete Streets planning. Among them was the Carbon Reduction Program (CRP), which was authorized to disperse $6.4 billion on projects that—as the program’s name would suggest—reduce carbon emissions. It is the first federal program created within the national highway program explicitly focused on reducing carbon emissions and most of the eligible uses for the funds are focused on getting more efficiency out of the transportation system by moving trips to less polluting modes.

Unfortunately, even this small amount of funding dedicated to shifting travel to emissions-free modes is under threat. As we wrote last summer, this formula program has a significant loophole in it that could allow up to half of its funds to be spent on projects that actually increase emissions. And now, a group of Nevada state legislators want to require over one-third of the funding to be reserved for truck electrification only.

Nevada lawmakers set a low floor

Introduced last month, Nevada assembly bill AB184 would stipulate that 35 percent of CRP funds—or approximately $3.9 million dollars per year—that Nevada receives would go into a newly created funding pot called the Account for Clean Trucks and Buses. With money in this account, medium- and heavy-duty vehicle (MHDV) purchasers could receive a subsidy for buying electric versions of these vehicles, so long as they meet minimum criteria for how they’re operated.

Electrifying MHDVs does not violate the CRP. Deployment of alternative fuel vehicles is indeed one of the thirteen types of projects that these funds can be used for, and it is an important use: over one-fifth of transportation emissions come from MHDV emissions. In addition, electrifying MHDVs would have significant public health benefits for communities across the country (especially those living near ports, both inland and waterway). It is for these reasons that the Coalition Helping America Rebuild and Go Electric (CHARGE)—which Transportation for America co-leads—outlined MHDV electrification as one of three principles that should guide the electrification of our automobile fleet. However, AB184 has flaws in its execution and its decarbonization logic that ensures it would be no more than mining public funds for (minimal) private gain.

Click here to read CHARGE’s recent report on how electrification investments (including electrification of MHDVs) can advance climate goals.

As it is written, AB184 has three requirements for contractors to receive a rebate for their purchase. First, they must agree to operate or store their electric MHDV in Nevada for at least five years. Second, they must agree to operate said vehicle for at least 5,000 miles or 1,000 hours per year. Third, at least 75 percent of the time the vehicle is in operation must be in Nevada. This means that, in order to receive a rebate, purchasers would only have to operate an MHDV for 18,750 miles or 3,750 hours in Nevada. According to Department of Energy (DOE) data, this is less than one-third of the amount that an average Class 8 truck travels. If the taxpayer is going to help pay for these trucks to displace gas-powered emissions then these trucks should be used to the maximum extent possible throughout their useful lives.

Robbing driving reduction to pay for driving electrification

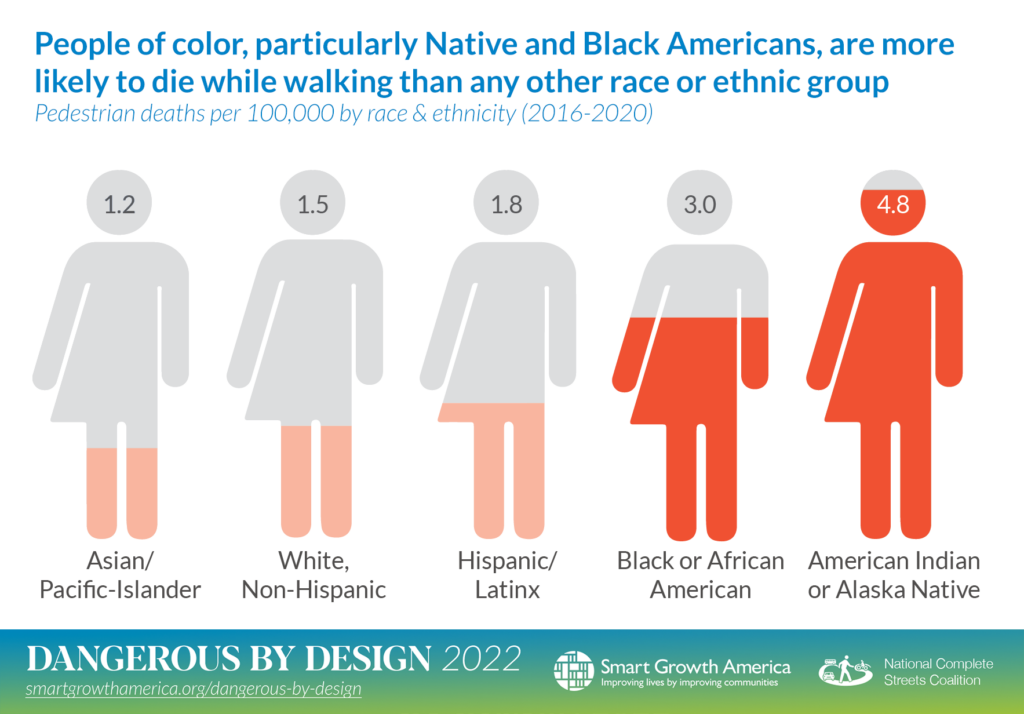

Electrifying the vehicle fleet across the country is absolutely essential. It must be done. But it is just not sufficient to meet our climate goals (much less our equity, public health and economic goals). Just like we couldn’t make HVAC systems maximally efficient while keeping the windows in buildings open and still meet our emissions goals, we can’t electrify the fleet and force people to drive more, farther every year, and meet our climate goals. The CRP is an important element in allowing people to move in more efficient modes.

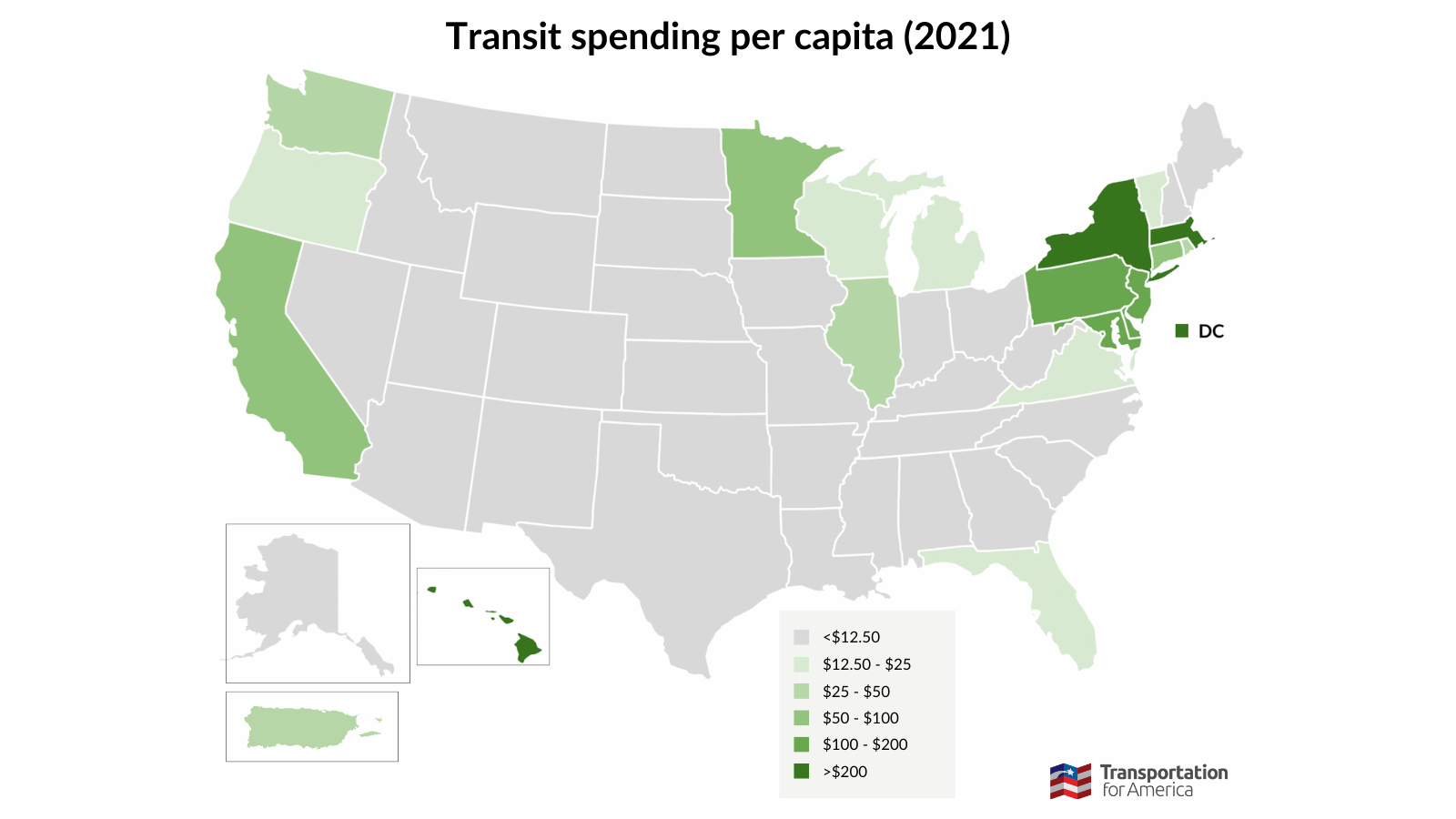

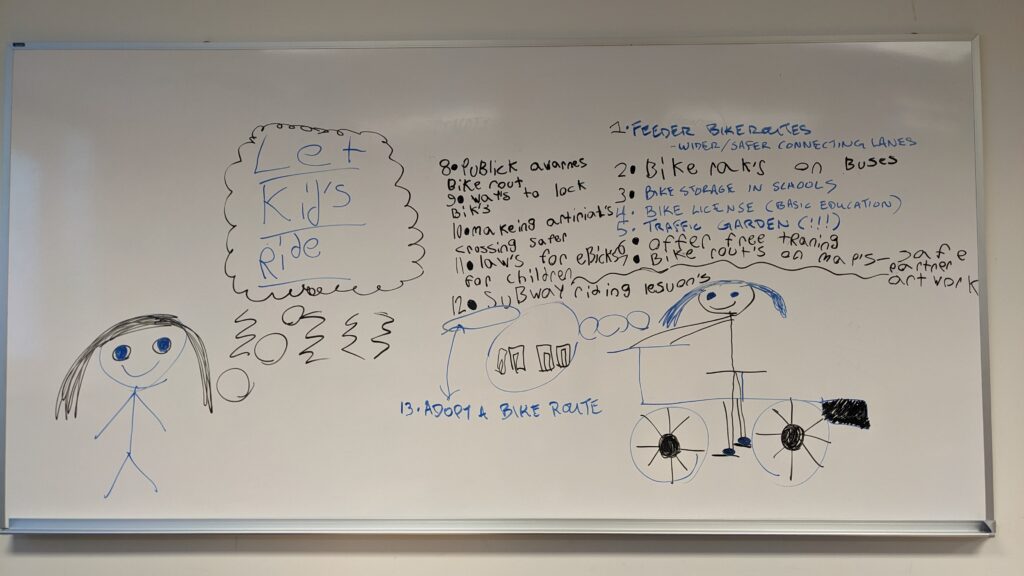

The CRP has thirteen eligible use categories—including public transportation capital projects and building active transportation infrastructure—but there are multiple other programs specifically intended to electrify MHDVs. These include the Bus and Bus Facilities Grant, the Clean School Bus Program, and the National Highway Freight Program. Importantly, many of these provide for the construction of public infrastructure, such as recharging facilities, that will induce private actors to purchase electric MHDVs on their own. More effective than incentives are efforts like in California to simply require newly-purchased drayage trucks to be electric starting in 2025, with all registered trucks being zero-emission by 2035. In addition, the infrastructure law and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provide further investments in port electrification, as well as a tax credit explicitly for qualified commercial vehicles that simply hasn’t been implemented yet.

AB184 doesn’t address reducing how far people need to drive or giving their constituents access to more low-emissions travel options. As CHARGE, Transportation for America, and the Climate and Community Project have all noted, any proposal to electrify existing transportation infrastructure without significant reductions in how far people need to drive is fundamentally insufficient. If Nevada already has a strong plan to ensure that the state isn’t cutting into the gains made by electrification with investments that cause more vehicle travel overall, then it might be time to dip into CRP funds as they have proposed. If not, the state DOT and legislators need to consider whether the emissions benefits of this diversion is sufficient to justify it.

Considering that the rebate program as currently formulated would provide at least $175,000 (with potential increases for purchasers who meet additional criteria, such as being a minority- or veteran-owned business, AB184 could only be used for buying about twenty-two electric Class 8 vehicles. When combined with the DOE data, this means that the standards for this rebate are so low that they might only replace eight Class 8 trucks. The question for Nevada lawmakers is whether that benefit is enough to justify taking this funding from other needs that might be hard to fund any other way.

The bottom line

The central flaw of AB184 is simple: there is no consideration of whether there are better uses for CRP funds today or in the future. There is no consideration of other needs such as improving transit or active transportation and whether the state has access to sufficient funding elsewhere to address these needs before a portion of this funding is diverted. Additionally, Nevada lawmakers are creating a program that could be exploited by those who want to expand their MHDV fleets on the taxpayer’s dime without having to demonstrate sufficient use of those vehicles or emissions reductions.