The next federal transportation reauthorization won’t pass for another three years, but change can still happen at the state level. Here’s why state legislatures play a key role during this time and what they should do with that power.

By passing the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA, or infrastructure law), the federal government authorized transportation programs through November 2026. There are occasionally new programs proposed, such as Rep. Cori Bush’s BRT Bill, and annual fights to ensure that discretionary programs which didn’t receive advance appropriations are adequately funded. However, Congress’s general dysfunction likely means that no significant new transportation legislation will be passed at the federal level. The infrastructure law left a great deal of power in the hands of the states, and what states choose to prioritize will impact our safety, access, repair, equity, and climate goals for years to come. Therefore, it is a critical time for state legislatures to pick up the slack, and inaction is itself an action.

The state legislature behind the curtain

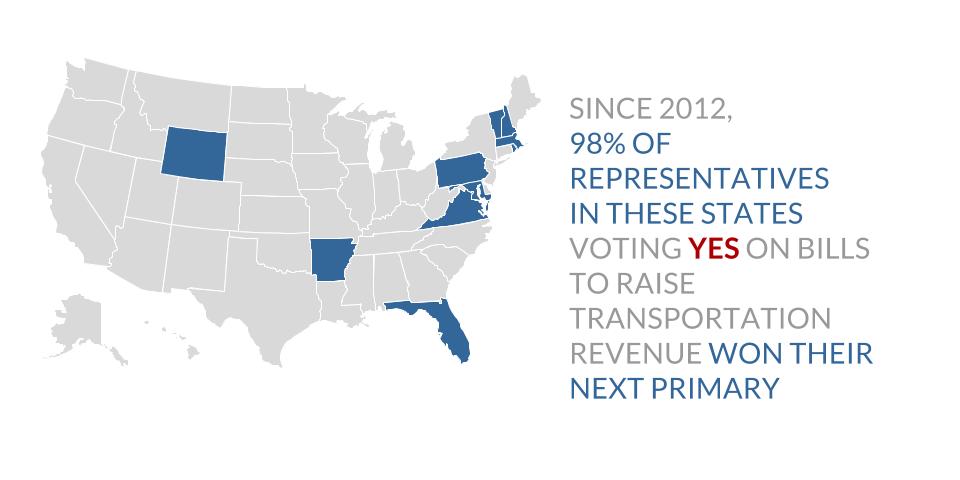

State legislatures have always had a critical role in determining what transportation networks look like. In many states, a significant portion of the transportation budget comes from state coffers, not federal funds. Illinois and Washington are two states whose legislatures have passed significant spending packages in recent years. In addition, no matter where money comes from, state legislatures have significant leeway over how that money is spent. They can set conditions on spending and conduct oversight of state DOTs whose urban and rural roads are disproportionately deadly. They can also direct state DOTs to spend funds on modes that aren’t just driving, such as investments in rail and subsidizing transit operations.

The passage of the 2021 infrastructure law made state legislatures’ role even more important, as it made a significant sum of money available to the states. However, a significant portion of these federal funds are being distributed through formula programs that don’t come with few strings attached, which means it could easily further entrench the unsafe, unsustainable status quo. Left to their own devices, state DOTs can profess to use that money in the name of good (setting a goal to limit the number of pedestrian fatalities), while ignoring key problems (setting a goal that’s higher than the actual number of fatalities in the previous year). The same could be said for goals of reducing emissions and ensuring that transportation’s inequitable past doesn’t become its future: without state legislative action, much of the funding from the 2021 infrastructure law could be used to make these problems worse.

Importantly, with many legislative sessions coming to an end in 2-3 months, state legislators’ windows for action on a number of these issues are rapidly closing. As federal funds go into state piggy banks, safety, sustainability, and equity could all suffer without sufficient guidance to state DOTs. As funding for passenger rail is distributed, state legislatures risk their state missing out on popular transportation options. At the same time, alarms are sounding from transit agencies facing a fiscal cliff. If state legislatures don’t step up, any promise in the infrastructure law could very well go unrealized.

What state legislators can and should do

The first step state legislators can take is to rethink the status quo on road spending. Rather than building new infrastructure that further divides communities, state legislatures should prioritize maintaining the infrastructure they have built that’s useful, and reconnecting communities where old infrastructure does little more than divide. Rather than getting people to their destinations as quickly as possible, states should prioritize getting them there safely and ensuring they don’t have to travel as far to meet their needs in the first place. These are all specific, clear transportation goals and priorities that state legislatures can direct their state DOT to pursue.

To do this, they simply need to follow the lead of, and improve upon, state innovations that have already been implemented. In Colorado, the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Reduction Planning Rule requires metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) to plan for greenhouse reductions by limiting projects which will increase emissions and promoting those which expand multimodal options. Minnesota lawmakers are pursuing legislation similar to that of Colorado. In 2021 Maryland established a required baseline for transit maintenance funding, securing it from the whims of annual budget conversations. This is an important step that other legislatures should consider. Relatedly, Virginia’s SMART SCALE is a transportation project evaluation tool that ensures factors like improved safety, increased accessibility, and efficient land-use make a project more likely to get funding from Virginia Department of Transportation. Unfortunately, no state has copied their work yet.

When it comes to passenger rail, state legislatures should take advantage of new, time-sensitive opportunities. The 2021 infrastructure law created the Interstate Rail Compact Program (IRC) to help states work together to develop regional passenger rail networks across the country, as well as the Corridor Identification and Development Program (CIDP). However, given shifts in Congress, both of these programs may receive less funding in future years. Legislators interested in bringing rail service to their state should not allow this opportunity to pass.

Finally, as transit agencies approach fiscal cliffs over the next few years, state legislatures should move to give them the operating funds necessary to not only maintain current service, but increase it. Although federal Capital Investment Grants are still available to agencies, financial support for operations that the federal government distributed during the pandemic is unlikely to come back any time soon. Any legislature that’s serious about maintaining, if not expanding, the role of transit in their state to avoid increased emissions must provide direct support to agencies for operations.

The bottom line

Transportation spending can be a lot like the game plinko—although a lot of money may be poured in at the top, where it actually ends up depends on decisions made at the state and local levels in between federal reauthorizations. As we approach three-and-a-half years until the next federal infrastructure law, the power over what our transportation system looks like rests in states’ hands.

Advocates can help steer their representatives in the right direction by contacting them and highlighting key transportation concerns. Include specific suggestions on how they can tackle the issue, such as direct more funding towards transit or support policy proposals. During legislative sessions, advocates also have an opportunity to engage through testimony on transportation issues that are most important to them. Ask your state leaders: Will you accept the current deadly, carbon-intensive, community-destroying status quo? Or will you usher in an era of safer, more sustainable transportation that brings our communities together?