Despite its name, the federal “value of time” guidance doesn’t actually value travelers’ time at all. Instead, this arcane but influential measure focuses on one thing: vehicle speed. The result is more dangerous, less convenient travel for everyone.

Bear with us for this one.

This may seem completely arcane, but the federal value of time guidance has monumental implications because assigning a value to time gained or lost guides nearly every transportation decision. This guidance instructs transportation agencies on how to measure (1) the current performance of the existing transportation system and (2) the cost and benefit of future projects. In other words, when agencies are deciding whether to add a crosswalk or expand a highway, they use this guidance to help inform their decision. Unfortunately, current guidance is flawed, costing taxpayers’ time, money, and safety.

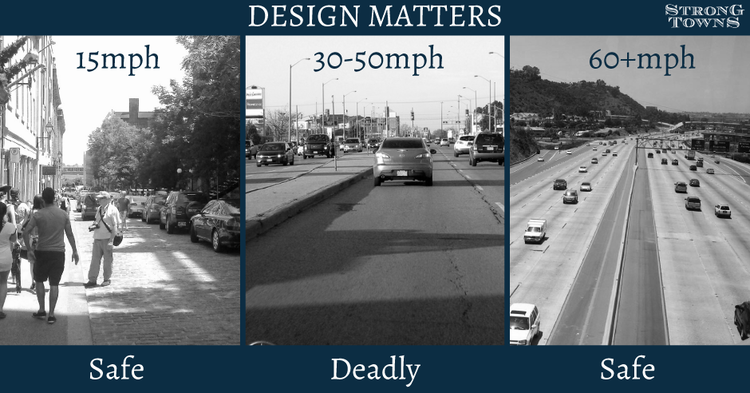

“Time savings” are mainly determined by vehicle speed

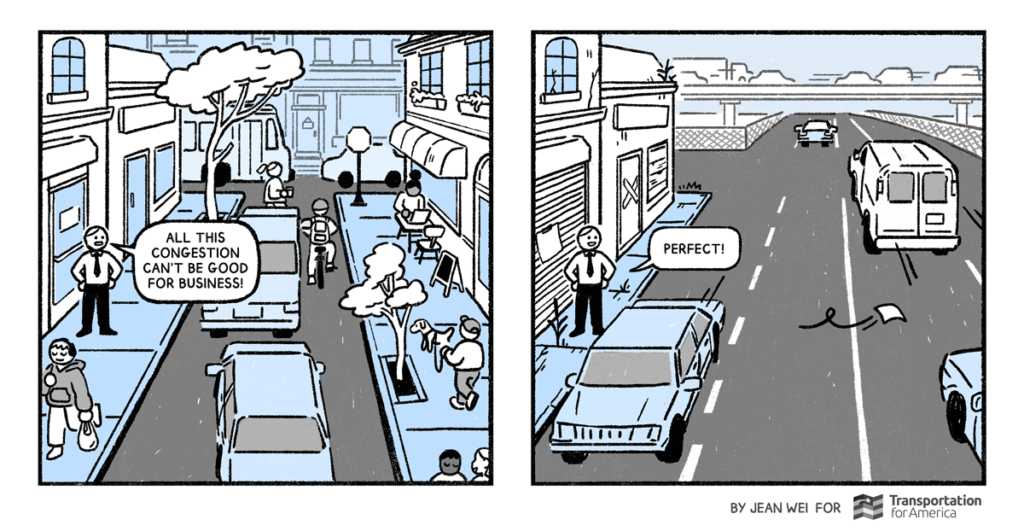

When modeling for time savings, agencies focus on only one thing: getting and keeping vehicles moving. As long as vehicles are moving faster, agencies predict that their new project will save time. It doesn’t matter if, to speed up vehicles, daily trips end up being longer and taking more time overall.

Imagine you’re driving to a grocery store located on the left side of a busy street. But allowing cars to turn left safely on this intersection would halt the flow of oncoming traffic and slow down car travel through the corridor. Instead, you have to drive to the next intersection and make three right turns to reach the grocery store. Your trip is longer, but overall, vehicle speeds stay high. This would be considered a time savings win under the current system.

Expensive roadway expansions justified by projected time savings because they’ll result in less traffic—promises that often never materialize thanks to induced demand—are another example. As the State Smart Transportation Initiative recently pointed out, as roadways expand and speeds increase, people just tend to spread out more. “So, while the distance a traveler is able to reach in a given amount of time is increased, there are not necessarily additional destinations available to them,” as Aaron Westling at SSTI noted. Even if added lanes miraculously solve traffic and cars can go twice as fast, people will still find themselves taking longer trips as destinations move further apart.

How do agencies get their numbers anyway?

For vehicles and transit, agencies measure end-to-end travel times on a segment of roadway. Yes, you read that right—they aren’t measuring how fast people are able to travel from their origin to their destination but how fast people can travel on individual segments of road.

Agencies can often believe they’ll help cars move faster, even though they’re relying on outdated or flawed models. Failure to account for induced demand is a great example of this. The result: time and money are wasted on projects that make travel longer, more dangerous, and in some cases, even slower.

Whose time is considered worth saving? Whose time isn’t even being measured?

The value of time guidance puts heavy value on the “nine-to-five” (or peak period) business trip. Travel to and from work is given greater importance than what the guidance refers to as “personal” or “leisure” trips like travel to schools, daycares, and doctors’ offices, let alone off-peak/non-traditional work trips that are more common for low-income workers. To explain this imbalance, the guidance claims that the schedule of work, dictated by the employer, creates more structure for measurement, even though schools and daycares track late arrivals and doctors can cancel appointments when patients arrive late.

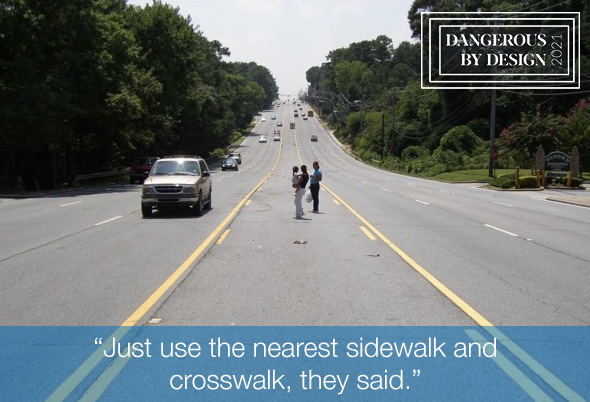

Local travelers get the worst of this bias. While agencies focus on making it easier for cars to move quickly, a highway that destroys a community (see I-49 in Shreveport) is easily justified on the grounds of time savings, even if locals lose 15 minutes having to walk out of their way to cross a now-dangerous street or can no longer walk to their destination at all because a new highway blocks their path. The impact to their time is literally never considered as part of the process of developing such a project.

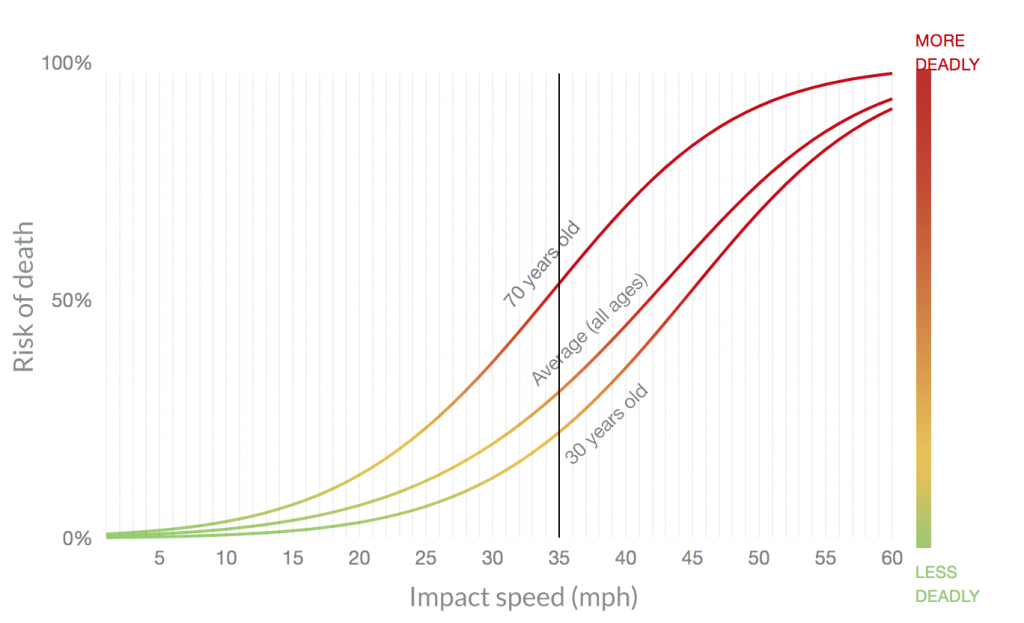

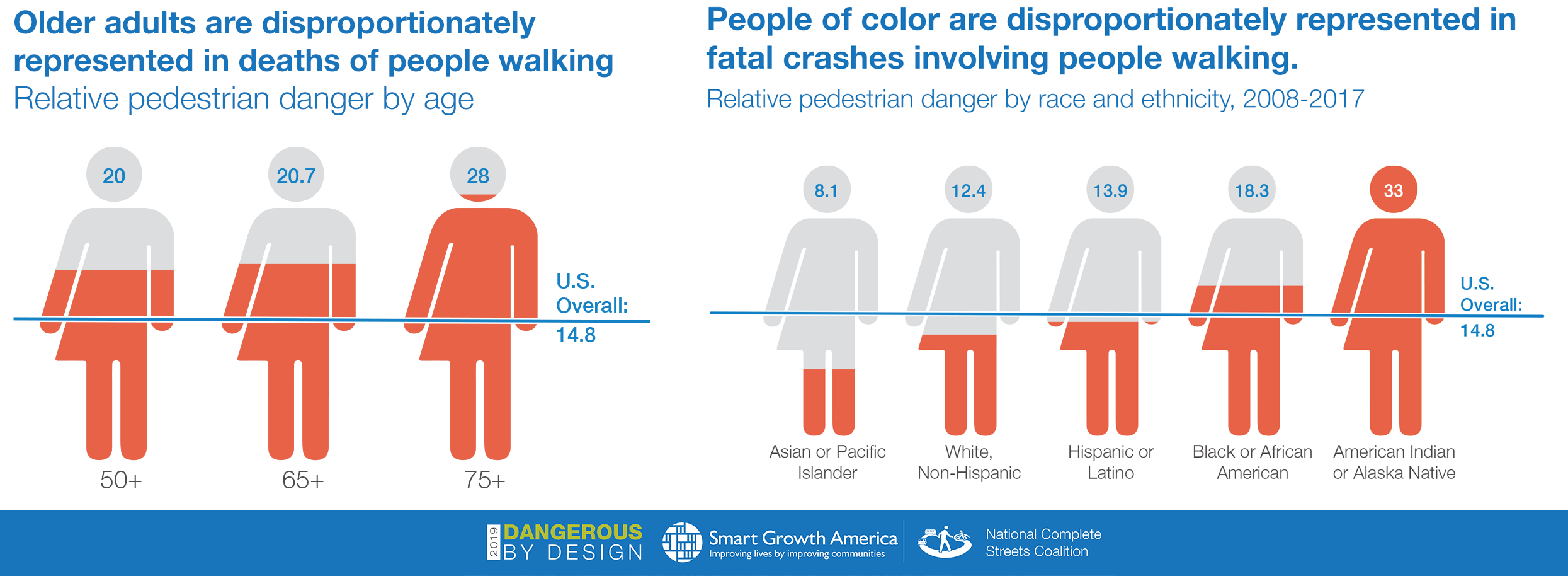

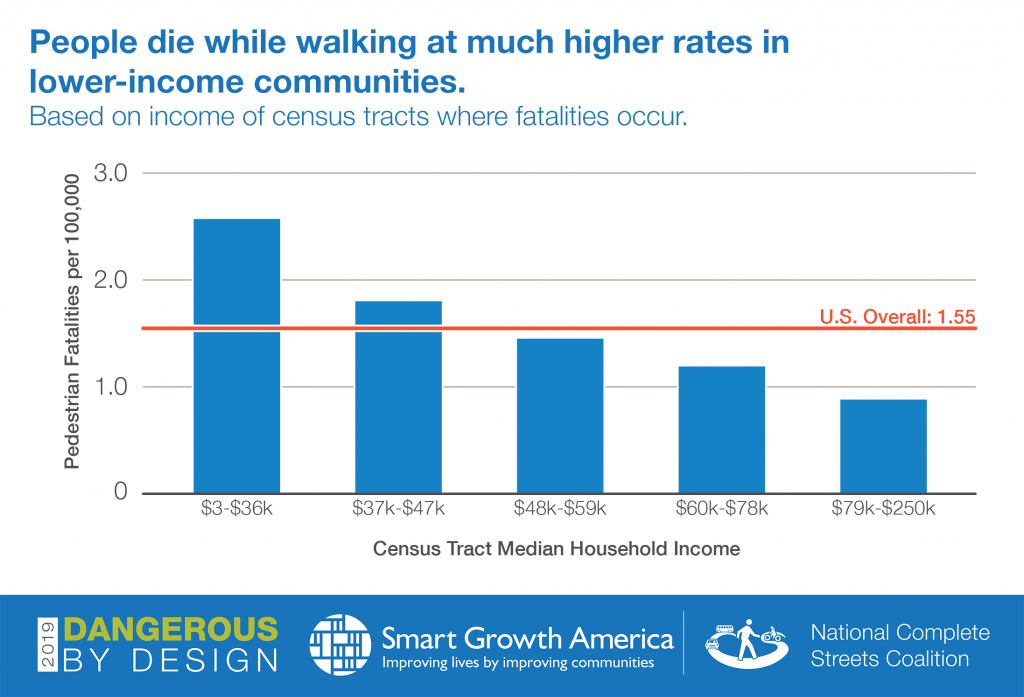

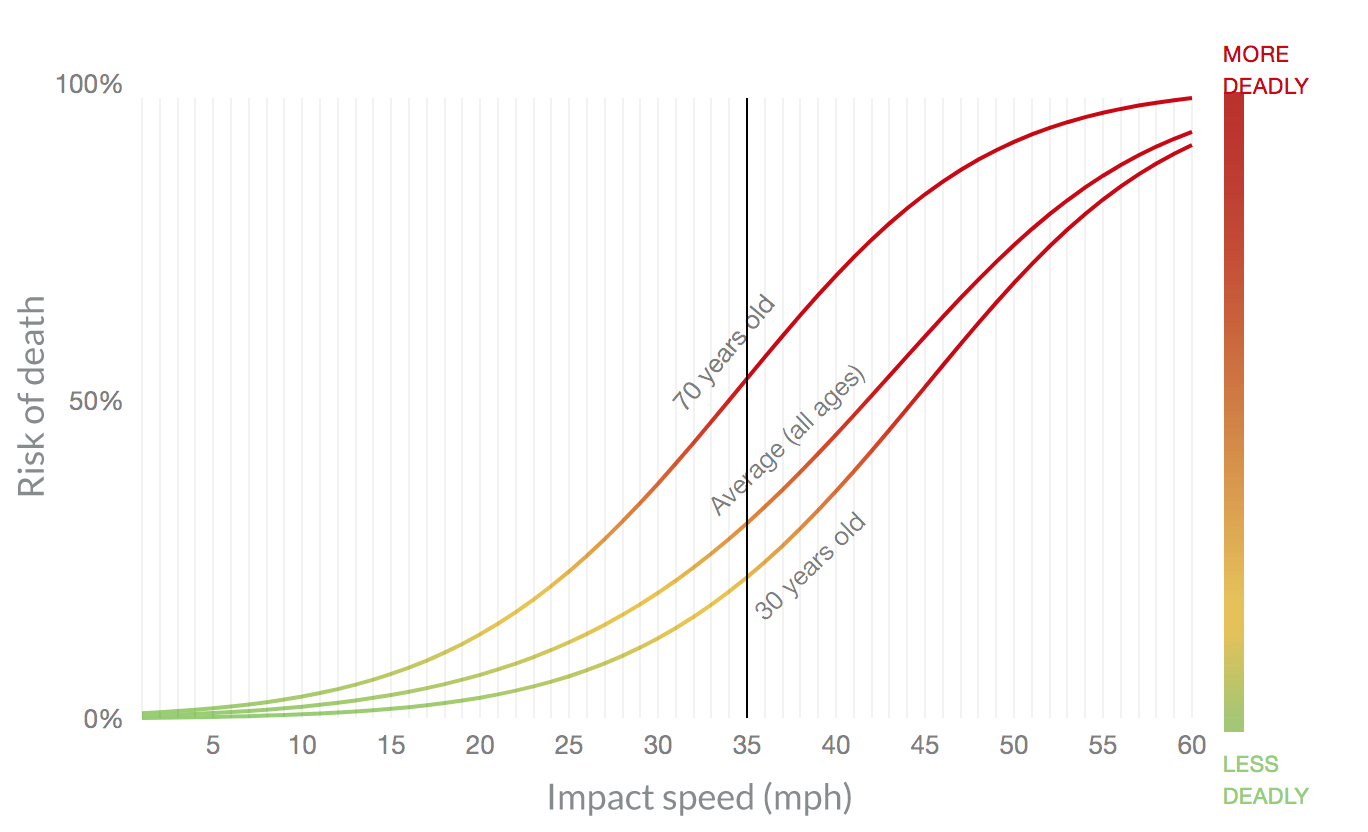

As another example, the small changes that result in faster car travel often make travel for other people more dangerous, which is never considered. Look no further than slip lanes, which exist solely to keep vehicles flowing quickly through intersections, directly through marked pedestrian crossings. These projects have a disproportionate impact on the time and safety of the people walking who have to cross bigger distances and make extra crossings. In most metro areas, low-income people of color are more likely to be pedestrians, while the white and wealthy are more likely to be driving and enjoying the “time savings” this deadly design feature provides.

On top of this, in traditional travel modeling processes, pedestrians and cyclists aren’t even considered. Federal guidance assigns a possible value for active transportation, but only if agencies can figure out on their own how they’ll measure it. Transportation agencies end up being able to assign a value to driver time savings, however inaccurate, but not to cyclist and pedestrian time savings. Active transportation is a cheaper, healthier way to travel that’s far better for the environment than vehicle travel, but we stack the deck against realizing those benefits.

The value of time savings of longer distance trips is also worth more, so a ten-minute saving for a business traveler from DC to Miami is given more weight than saving ten minutes on a daily, local commute.

Worse still, value of time is scaled to household income. A wealthy person with more choice on where they live and more ability to pay is valued higher when they save time. Meanwhile, someone who works minimum wage, who has fewer options for places to live, is valued less in time savings.

Recommendations

The Biden administration should repeal the current value of time guidance and replace it, taking into account the advice below. Current federal guidance accomplishes little in actual time savings, and what little time it does save often benefits only a privileged few at the expense of the safety and convenience of all other travelers. All travelers deserve quick, safe, and convenient access to the goods and services they need. This is true no matter how you travel, no matter where you travel, and no matter when you travel.

Stop overestimating the value of time

One issue is that the models overestimate how exactly much travelers truly value time savings. One of the easiest ways to determine this is to look at drivers’ willingness to pay tolls to travel faster. Surveys find little evidence that people are willing to pay for time savings. Among others, there are examples of people in Texas sitting in traffic to avoid tolls, or drivers avoiding a new tolled bridge in Louisville which undermines the very basis of monetizing this benefit.

Establish a minimum threshold for time savings

If a person saves five minutes on their commute each day, that won’t translate to sufficient time for work or a hobby or some other new, productive use. That’s why economists dismiss any time savings less than 10 minutes as “noise,” but under federal guidance, time savings as low as 10 seconds are considered valuable. Establishing a time savings minimum would ensure that costly projects result in real benefits to taxpayers.

Calculate the true time-saving value of other forms of transportation

People also value their time differently. Someone who bikes to work might prefer this method of travel over sitting in traffic. If getting some exercise during their commute means they can avoid a trip to the gym, a person might even feel that they’ve saved time—even though these time savings wouldn’t show up in agencies’ calculations. Agencies also ignore the benefits of forms of transportation like public transit that allow people to be productive by working, reading, or relaxing more on their trip than someone driving a car.

Calculating these benefits wouldn’t be difficult and could result in better transportation for everyone. If guidance included clearer and equally promoted value on health benefits and credited multitask transit riding as higher time savings over single task driving, agencies could better prioritize other modes of travel.

Stop tipping the scales for nine-to-five commuters

As teleworking during the pandemic altered travel schedules, agencies should also take advantage of the opportunity to reevaluate their emphasis on the nine-to-five business trip and give nontraditional work schedules, as well as necessary trips outside of work, more consideration.

Remember: it’s about time, not about speed

There are more ways to reduce time than simply increase vehicle speed. Take freight as an example. To save time, freight logistics experts don’t wait five years for a capital project as agencies do for roadways (and the benefits for these road expansion projects are quickly eroded by induced demand). In that time, freight companies make hundreds if not thousands of changes to their operations and practices that earn them more benefit than merely moving trains faster. They create redundancies in their system, which translates to choice for consumers. Furthermore, they recognize that the real time savings comes from warehousing and positioning needed goods closer to the customer, so that their trips become shorter overall. Yet nearly every model and metric we use ignores the growing length of our trips.

To actually save travelers’ time, agencies need to take local travelers into account and consider how projects impact the length of trips, not just how quickly cars can go.