Focusing on whether the infrastructure law was “good” or “bad” will fail to shape how its historic cash is spent over the next five years. That’s precisely why T4America is pressing on to enable USDOT, states, metro areas, and local communities to maximize the potential of this flawed legislation.

A few weeks ago, Chuck Marohn from Strong Towns had America Walks CEO and former Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn on his podcast. It was a terrific journey through Mayor McGinn’s transition from local advocate to Mayor of Seattle and now to the CEO of America Walks, but they also talked at length about last year’s $1.2 trillion, five-year Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA.) Strong Towns was—like T4America—fairly critical and saw an immense amount of money being put into the same old broken way of doing things, while adding numerous small programs intended to accomplish some worthy goals. Here’s Chuck Marohn (around 36:00):

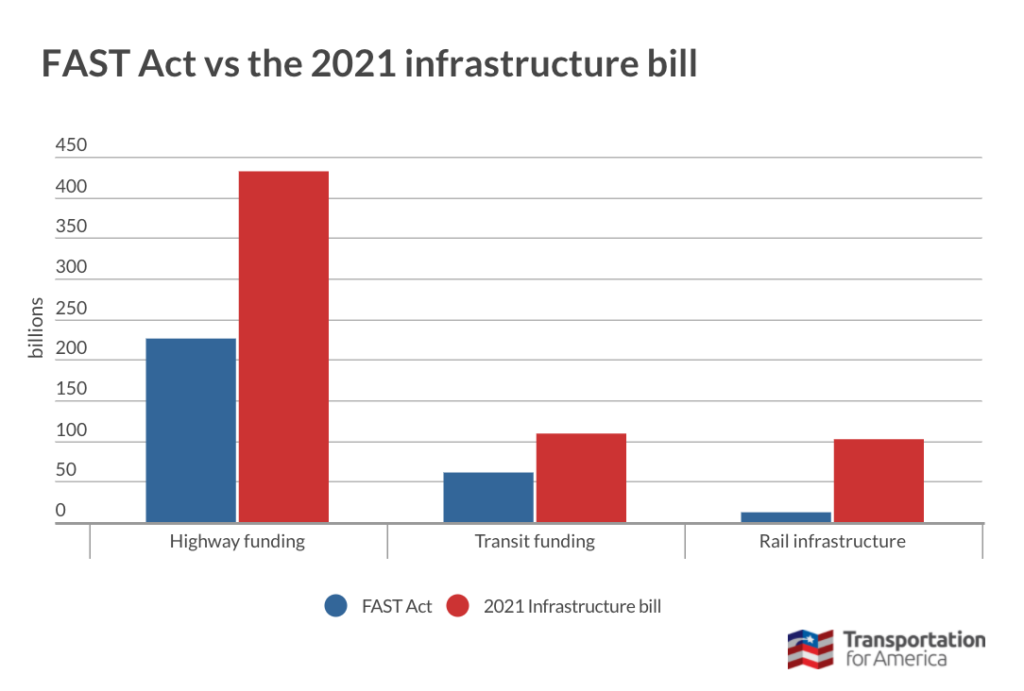

From the very beginning, when it was just a proposal from the administration, I pointed out that [the IIJA] was really just a highway bill with a bunch of other sweeteners along the way to build the coalition to get this thing approved. And because of that, I was against it.

That’s not far off. When it comes to the stated goals of improving safety or reducing emissions, you can’t just create small new programs (tear down divisive highways!) to solve problems that are still being created by enormous pots of money (build new divisive highways!) As T4America Director Beth Osborne noted when the IIJA passed, it failed to reform the federal program around our three, simple key priorities.1:

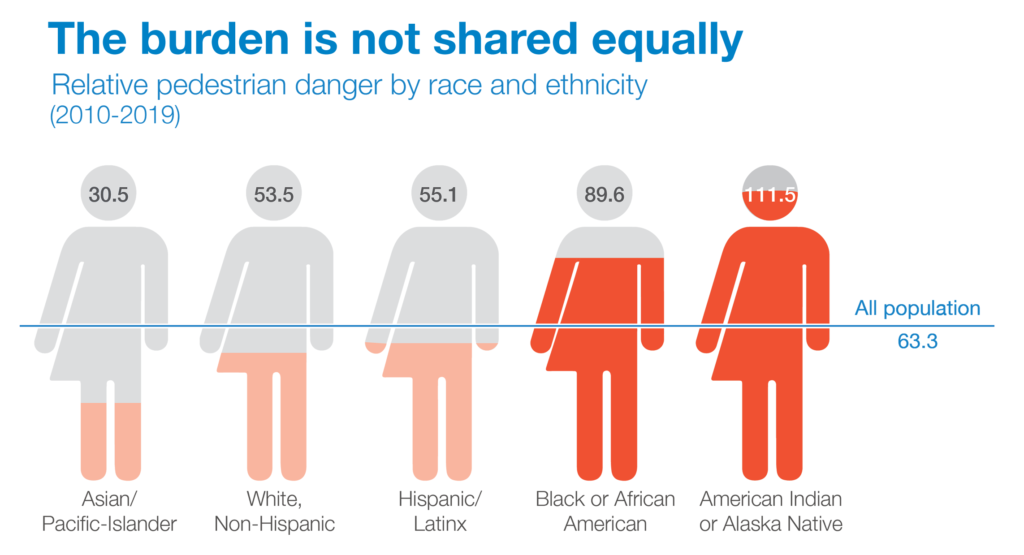

As we have stated before, the transportation portion of the infrastructure bill spends a lot of money but fails to target it to the needs of the day: building strong economic centers, providing equitable access to opportunity, addressing catastrophic climate change, improving safety, or repairing infrastructure in poor condition.

But taking a stand one way or the other on the IIJA now is also maybe a bit moot—the horse is out of the barn. What definitely matters now is how this money will be spent over the next five years—decisions already being made that desperately need to be influenced by reform-minded people. Mike McGinn’s answer to Chuck’s question around 37:45 is worth excerpting heavily:

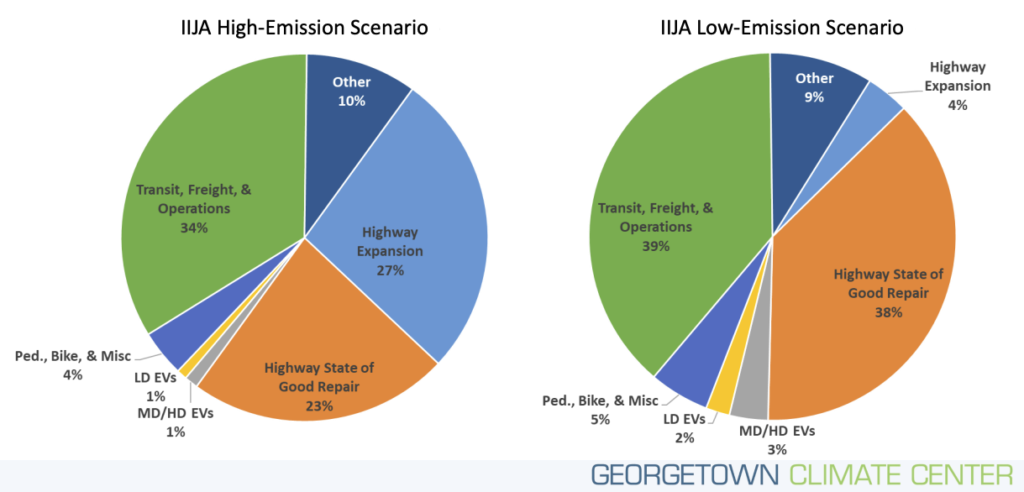

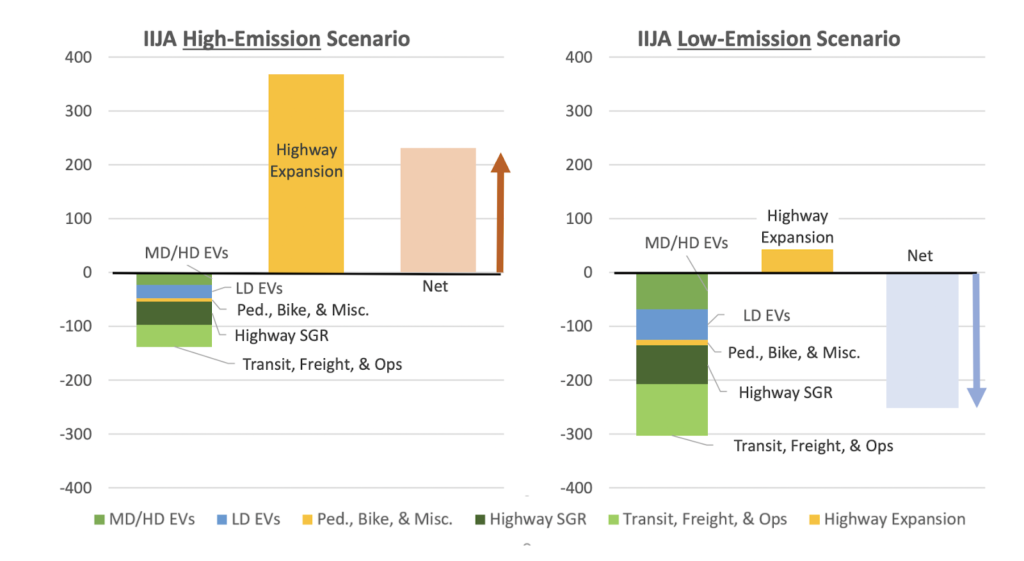

It’s entirely dependent on how the money is spent. 70 percent of the money is flexible money that goes to states. … The pots of money for transit, for alternatives are bigger than they’ve ever been. People are saying that’s a good thing and I agree, that’s a good thing, but those pots are only 30 percent of the overall funding. We do live in a world where so much of the money comes from the feds, I think that people like us at America Walks and the others in this arena, have to continue to push them to reform how they do it.

While there are times that the whole federal transportation program, and federal involvement in general, seems counterproductive, the feds are here to stay in transportation. And the IIJA is yet more evidence of how the program continues to get support even in today’s divided political environment. So T4America is going to engage in the federal transportation project to reduce the damage it is currently doing and steer the ship in a better direction. To that end, we are focusing our work on at least two things for the next few years:

- Helping USDOT maximize every single dollar they have at their disposal.

- Shaping how states and metro areas spend this historic level of flexible cash.

On that first point, USDOT and the administration are making lofty promises about the benefits the IIJA will bring. It will finally modernize our infrastructure. It will be used to improve equity across the board. It’s going to make walking and biking safer than ever. It’s going to help reduce emissions. This is a risky strategy for the administration. Because states control the bulk of the funding, to realize these promises, the administration has to trust that state DOTs as a group will fulfill these promises for them. This is a group that also has many members with a track record of pretending induced demand doesn’t exist, spending heavily on expansion with no plan for future maintenance, and thinking that eliminating traffic congestion is a viable solution for lowering emissions and tackling climate change.

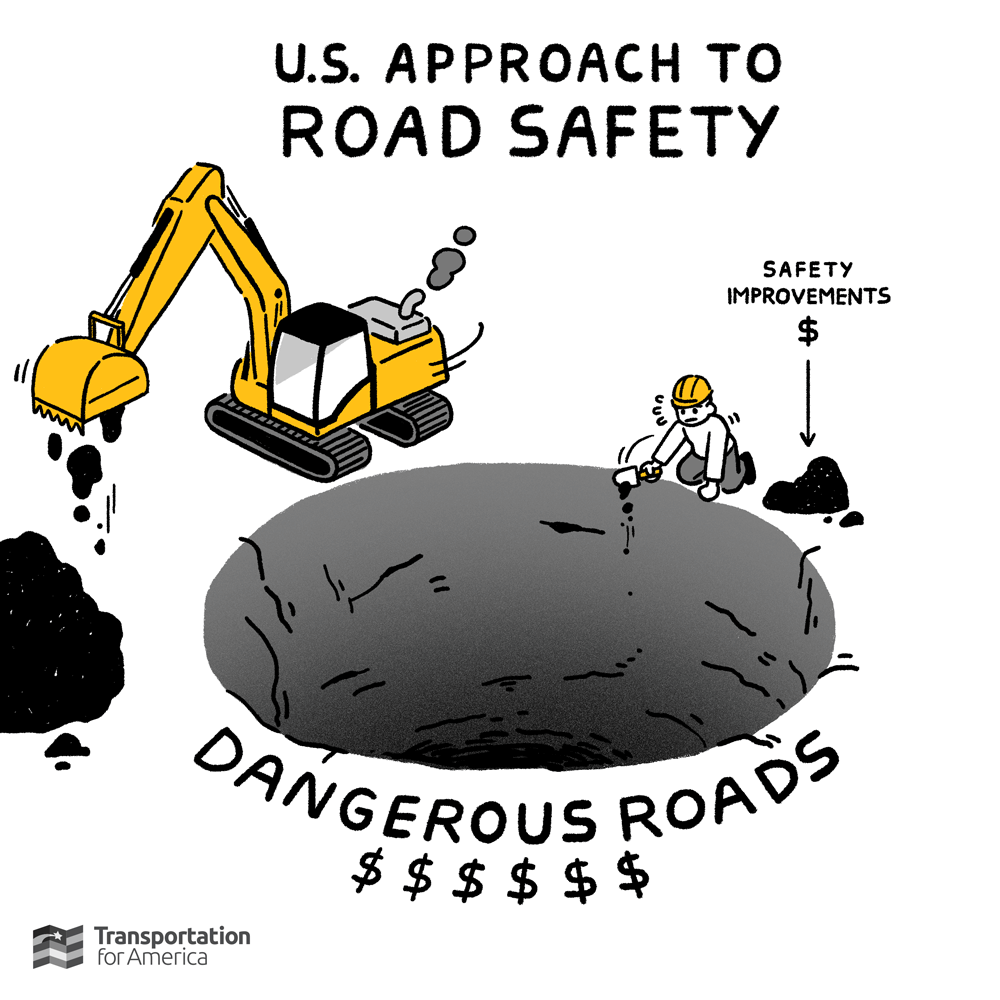

The Biden administration seems to believe that the law’s many, good, small, new programs—like Reconnecting Communities to tear down divisive infrastructure or Safe Streets for All to directly fund local street safety interventions—were worth the law’s massive historic increase in status quo programs that will continue to create the problems these smaller programs were created to fix. While this approach amounts to trying to fill up a hole with a teaspoon that’s being dug with a giant excavator, it also means that USDOT must absolutely maximize every scoop.

Every single dime at their disposal must be spent on projects to do the most to counteract the billions that can and likely will be used to build new roads and highways that increase emissions, lead to more traffic deaths, and further divide communities. They cannot spread the money around to keep everyone happy. They cannot choose projects that fail to bring numerous benefits. Precisely because states may not rise to the occasion, USDOT must maximize every cent that they do control in some fashion, like the $200 billion in competitive grants.

On the second point, the 70 percent of the funding controlled by the states is ostensibly known as “highway” funding, but it’s also incredibly flexible. If a state wants to spend it all to prioritize repair, remove roads that cut neighborhoods in half, and build sidewalks in every community that needs them, they are free to do that. This is why T4America will be working over the next five years to equip advocates and forward-thinking transportation agencies to maximize that flexibility and do something different. Absent this effort (from hundreds of other national or local groups and millions of other engaged advocates, we should add), this historic infrastructure spending will largely go right into the same status quo of the last decade, producing more roads and highways to maintain, neglecting repair needs, designing streets for speed and creating danger, and failing to connect as many people as possible to jobs and opportunity.

These outcomes above weren’t automatically guaranteed when the IIJA passed—the verdict will depend in part on specific decisions made over the next five years. When it comes to why we continue to work to shape the IIJA’s spending, we said it clearly last month:

The current system can’t fix the current system. We can’t outbuild our repair needs, expand our way to shorter commutes, or speed our way to safety. To solve these issues, we must be committed to addressing their root causes, which means decision makers at all levels need to rethink the traditional approach to addressing transportation issues. Our efforts now are aimed at facilitating that process and measuring the administration’s progress on their stated goals.

This post is part of T4America’s suite of materials explaining the 2021 $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which governs all federal transportation policy and funding through 2026. What do you need to know about the new infrastructure law? We know that federal transportation policy can be intimidating and confusing. Our hub for the new law will walk you through it, from the basics all the way to more complex details.