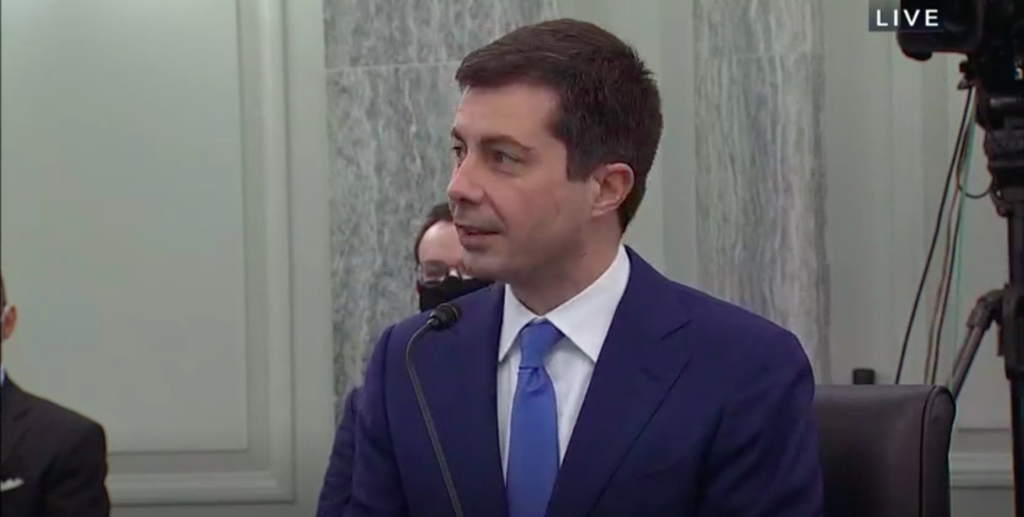

Tomorrow, Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg heads to Capitol Hill for his first hearing as Secretary, where the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee will question him on the Biden administration’s goals for infrastructure. We’ve been impressed by Sec. Buttigieg’s rhetoric so far—from his commitment to repairing the damage in Black and brown communities caused by urban highways to making fix-it-first his “mantra“—so we want to hear how he’ll make it happen.

Stimulus

- The administration is discussing a major stimulus package focused on infrastructure funding. Will that package specifically address climate, equity and repairing crumbling infrastructure rather than simply adding additional funding to the existing programs that have failed to address these issues?

- In the 2009 Recovery Act, Congress intended to spur job creation, but that was not how the infrastructure funds were targeted. In an attempt to move quickly, Congress defaulted to existing programs that were poorly tailored to address the issues at hand. How can we learn from that experience and do better this time?

Repair and maintenance

- You and the administration have repeatedly acknowledged the need to fix our transportation infrastructure: our roads, bridges, and transit. Yet, our current federal programs have not successfully been able to do this. Why is this the case?

- Can we get to “fix-it-first” with the way we currently prioritize funding?

Safety

- A recent report by the National Complete Streets Coalition found that pedestrian fatalities have increased by 45 percent over the last 10 years. Much of this has to do with dangerous street design and transportation laws that make safety for those walking and rolling an afterthought while making speedy vehicle movement the priority.

- Should we continue to have separate and parallel highway and safety programs, with the safety funding significantly lower than the highway funding? Can we address the safety crisis without fundamentally reforming the highway program?

- The INVEST Act, passed by the House last Congress, centered safety throughout the bill. Would you support centering safety throughout a transportation title instead of maintaining the status quo?

- Poor safety design has led to disproportionate safety outcomes for communities of color, often incentivizing these communities to break the law and risk interacting with police, or put themselves in harm’s way when navigating unsafe infrastructure. How can the federal transportation program require street designs which promote safety, particularly for vulnerable road users?

- Would you support requiring DOT to collect locations of all collisions resulting in death or serious injury, highlighting those involving cyclists and pedestrians, and produce a detailed map of an annual High Injury Network?

Transit

- Since 1982 highways have received approximately 80 percent of surface transportation funding and transit has received approximately 20 percent. Do you and the administration believe we can meet our transportation needs, respond to the climate crisis, and connect all Americans to jobs and services by continuing the way we currently distribute federal funding for highways and transit, often referred to as the 80/20 split?

- Do you support revisiting the 80/20 split to ensure funding goes to moving all Americans, especially our most vulnerable communities who rely on transit?

- This pandemic, more than ever, has highlighted the importance of transit in connecting our essential communities to jobs and services. The federal government has long maintained the position to not provide operating costs for transit agencies that often serve our most vulnerable communities. Do you support long-term federal operating support for transit agencies?

Equity

- This pandemic, more than ever, has highlighted the importance of transit in connecting our essential communities to jobs and services. The federal government has long maintained the position to not provide operating costs for transit agencies that often serve our most vulnerable communities. Do you support long-term federal operating support for transit agencies that connects marginalized communities to jobs and services?

- Poor safety design has led to disproportionate safety outcomes for communities of color, often incentivizing these communities to break the law and risk interacting with police, or put themselves in harm’s way when navigating unsafe infrastructure. How can the federal transportation program require street designs which promote safety, particularly for vulnerable road users?

- When we measure the transportation system, we look at the speed of vehicles. This ignores people without a car (disproportionately Black and brown people) out completely and it doesn’t look at a person’s whole trip — only their speed along a portion of it. Now that we can measure whole trips and all modes of travel to determine who is able to access jobs and essential services, shouldn’t this be one of our main performance measures?

- You and the administration have acknowledged that urban highways have caused substantial harm to the economic prosperity, public health and connectivity of marginalized communities. Do you support a program to address the damage caused to Black and brown communities by urban highways and other infrastructure with funding and programs to prevent displacement?

(Atlanta before and after I-75/85)

Climate

- A 2018 California Air Resources Board report found that, even after a ten-fold increase in the number of zero-emission vehicles, California would have to reduce vehicle miles traveled (VMT) per capita by 25 percent to achieve its climate goals. Should we wait for the full turnover of the fleet and hope that is enough? Or should we use every tool we have including investing in infrastructure and transportation policies that enable people to make fewer and shorter car trips?

- The more fuel burned and the more roads built, the more money a state receives for transportation. Do you agree that this is a perverse incentive which exacerbates both congestion and climate change?

- Traditional measures of a successful transportation system support high speed, free flowing travel. This means that a long-distance commute where a car moves very quickly would be considered more successful than a far shorter commute at a slower speed. Do you agree that designing roads with speed as the highest goal leads us to more and wider roads, more and longer trips, and more greenhouse gas emissions ?

- How should we reform the federal transportation program to encourage efforts to shorten people’s trips and allow them to travel using carbon free modes, like walking?

Congestion

- As you have stated, since the 1950s the federal transportation program has incentivized the construction of new highways. This has failed to solve congestion and, in fact, through a phenomenon called “induced demand” typical worsens congestion. In a recent report, Transportation for America found that while freeway capacity grew 42 percent in the largest 100 metropolitan areas, 10 percent more than population growth, congestion grew by 144 percent. In fact, congestion grew a great deal even in places that lost population.

- How can the federal government incentivize a more effective approach, including more balanced transportation options and less carbon-intensive modes?

- Should the federal government require the use of accurate transportation models that include induced demand and those traveling outside a vehicle so as to understand the true benefits and tradeoffs of a project being funded with federal dollars?

Rail

- With the administration’s push for passenger rail investments in many underserved regions of the country, how do you plan to expand high-quality passenger rail service to more parts of the country, particularly smaller communities already suffering the loss of essential air service?

- Do you agree that it is reasonable for rail passengers, just like airline, cruise, and any other passengers, to expect that the service will arrive and depart on time? What will you do to improve on-time performance?

- Most intercity passenger rail serves a multi-state region, with passengers regularly traveling across state lines. Regional collaboration to support passenger rail service is only as effective as coordination between governors, state departments of transportation, and other relevant state and local officials and entities. Would you support incentivizing the creation of interstate passenger rail compacts similar to the compact that governs the Southern Rail Commission?

The economy

- As the recent Amazon HQ2 search highlighted, businesses want to be located in walkable, transit-connected communities. Last week, a coalition of local Chambers of Commerce wrote to the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee and made it clear that businesses want the federal transportation program to invest in projects that improve people’s access to jobs and services—not increase vehicle speeds.

- Do you agree that safer, walkable, transit-friendly communities support economic growth and business creation?

- As a former Mayor, can you describe the economic impacts of investments in complete and safe streets?

- What reforms to the federal transportation program will support local economic development?