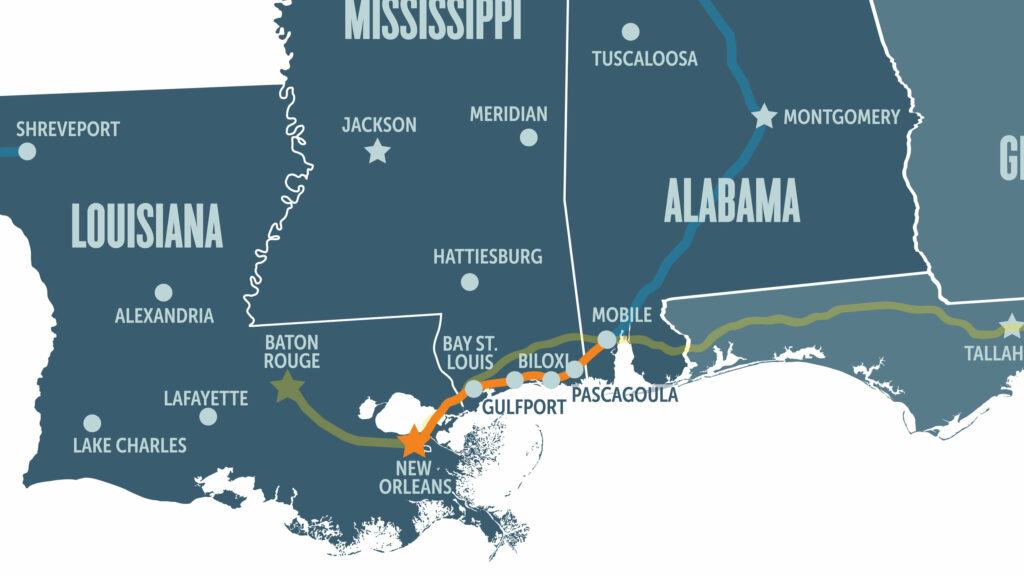

Federal advocacy and allies were essential to turning local momentum for passenger rail from New Orleans to Mobile—set to reopen this very year—into a regional, and national, success story.

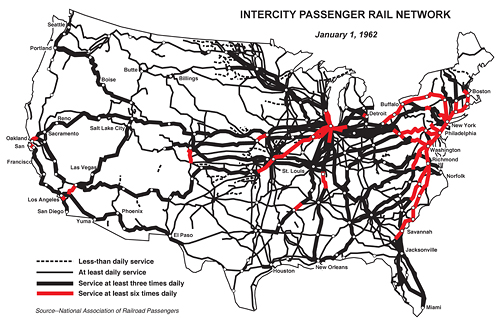

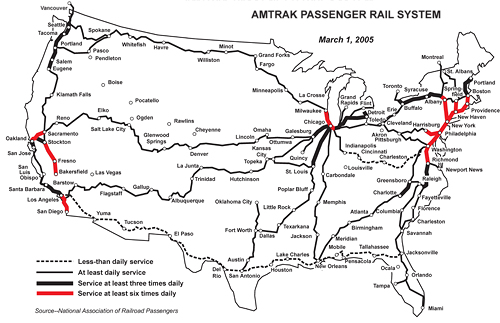

In recognition of recent progress for passenger service in the Coastal South, we’re releasing a four-part series exploring how unified regional and national approaches, supported by local advocacy and sound policy, can help create a successful passenger rail network. This is part three of the series, written by Mehr Mukhtar and London Weier. Read part one on the history of passenger rail, part two on building momentum for change, and part four on next steps for a national network.

As we explained in our last article on passenger rail in the Gulf Coast, in 2017, the Federal Railroad Administration’s Gulf Coast Working Group (GCWG) established that the region needs passenger rail expansion, first from New Orleans to Mobile—a major step in growing the region’s rail network. However, the restoration process would require infrastructure and operations investment.

At this point, Transportation for America had assisted the Southern Rail Commission with a variety of projects, including the 2016 ride-along that showcased local excitement for the restored route, but T4A started to take on a larger role to develop funding avenues, which could support the work that would come out of the FRA working group’s report.

Policy developments and funding

The first steps for the SRC and T4A was to find their champions, those legislators that would work to develop and support policy that could fund passenger rail restoration in the Gulf Coast. Senator Roger Wicker, former Chair of the Senate Commerce Committee; Senator Maria Cantwell, former Ranking Member and current Chair of the Senate Commerce Committee; and former United States Representative Peter DeFazio were key supporters of various initiatives brought to attention by the SRC and T4A.

A key initiative of the Southern Rail Commission, spearheaded by Chairman Knox Ross and Vice Chair John Spain, was advocating for the creation of passenger rail funding avenues on the federal level. They argued that federal funding sources, when combined with local financial support, would help build a cohesive and unified approach to restoration. Out of these efforts came two federal grant programs, the Consolidated Rail Infrastructure and Safety Improvements (CRISI) program and the Restoration and Enhancement (R&E) program, which provided the Gulf Coast with the resources needed to turn two decades of advocacy into action. These wins are a perfect example of the nationwide impact Gulf Coast efforts have had, as these federal grant programs provide funding for passenger rail expansion across the country.

The CRISI grant program makes funding available for projects which improve safety, efficiency, and reliability of intercity passenger rail and freight rail. In 2022, the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) was awarded this grant for the final design and construction of infrastructure needs for the Gulf Coast Corridor Improvement Project. These funds illustrate an exciting new phase of passenger rail restoration in the Gulf Coast as the SRC, Amtrak, and FRA step into the implementation phase. Additionally, funds matched by the state governments of Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama in addition to matches provided by freight rail corporations CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern Railway exemplify successful efforts to unify local, regional, and federal rail actors behind the project.

On the other hand, the Restoration and Enhancement (R&E) grant would aid in operations support. These funding opportunities not only provide the necessary resources to complete the New Orleans to Mobile train; they also provide the entire nation with an opportunity to implement rail restoration.

These successes led to a broad recognition of the need for rail compacts, not only in the Gulf Coast Region, but across the nation. The SRC had successfully advocated for funding avenues and seen initiatives across the Gulf Coast awarded funding for project implementation. Rail compacts were born out of the recognition that a cohesive and unified approach to implementing policy and funding mechanisms was required to develop intercity passenger rail services, as proven by the SRC’s efforts. The Interstate Rail Compacts grant program was created to provide financial assistance to support the activities of entities implementing rail compacts for the purpose of unifying governments along a corridor. This served as a valuable coordination tactic for aligning stakeholders to further the development of passenger rail in a given area.

Once an institution is created to help develop, guide, and oversee a passenger rail vision, it will need support to create an implementation strategy. The FRA created the Corridor Identification and Development Program (CIDP) to direct federal investments and technical assistance towards priority rail corridors for new or improved intercity passenger rail services. This collaboration would help develop corridors that are desired by local communities and states, while also advancing passenger rail connectivity not only within their region but across the country. In December 2023, the FRA awarded the SRC $500,000 through this program to develop the I-20 passenger rail corridor, which would connect Shreveport, Ruston, and Monroe to Dallas, Texas. The commitment of funds towards developing passenger rail service reflects the interest of the FRA in continuing to invest in the future of passenger rail in the Gulf Coast region, and nationally.

A notable characteristic of the CIDP is the desire to highlight what communities find valuable, rather than solely rely on a national vision to develop new routes.

Mobile and Amtrak negotiations

Aligning state and local support for implementation was a crucial aspect of revitalizing passenger rail service, as funding is hinged on subsidies from the states. The states of Louisiana and Mississippi both agreed to supply the match required for a federal grant covering operating assistance for six years in the project federal matching fund, while the state of Alabama opted out of picking up the costs. This shifted the responsibility of providing a match for the project to the city of Mobile, leaving confirmed funding sources for Gulf Coast service hanging in the balance.

After a series of long negotiations lasting almost over a year between Amtrak and the Mobile City Council regarding an operations agreement and station site lease, a deal has been struck. Mobile’s funding obligation would be split equally between the city, the state of Alabama and the Alabama State Port Authority. Although the details of sustained operating funding is still to be ironed out, this represents significant progress and partnership between these entities in the realization of the Gulf Coast service.

The next stop

With service expected to begin at the end of the year, the creation of policy and funding vehicles for improving and expanding passenger rail services across the country has been a tremendous success.

The expansion of passenger rail on the Gulf Coast reflects the common challenges our nation faces when expanding non-car-centric infrastructure, yet it is also an example of how to right those wrongs. The road to passenger rail restoration in the Gulf Coast has been a long one, but rail service is soon to resume. At the heart of this story are shared efforts between the SRC, FRA, Amtrak, regional and local elected officials, and community leaders, which have culminated in a new path forward for passenger rail in the region. In our final blog in this series, we’ll share the final lessons we learned from the Gulf Coast.